‘Golden Dome’ and the Illusory Promise of Invulnerability

US Missile Defense under Trump: Risks and Opportunities for Europe

SWP Comment 2025/C 50, 05.12.2025, 8 Seitendoi:10.18449/2025C50

ForschungsgebieteThe current US administration plans to protect the entire territory of the United States against any potential air or missile attack. The focus is on deploying large satellite constellations capable of detecting and intercepting long-range missiles shortly after launch. Even if only a fraction of this ambitious plan is likely to be implemented, it is probable that there will be progress in missile defense during the coming years. For Germany and Europe, the risks and potential benefits – especially with regard to space-based US missile defense – are difficult to assess at the current time. However, Europe can maintain the largest possible room for maneuver by avoiding an open confrontation over Trump’s plans.

In January 2025, President Trump announced the “Golden Dome” initiative, a US missile defense program based on an idea that harks back to a Cold War project. The new initiative was first mentioned in the form of a promise during Trump’s first term and was taken up again in the 2024 presidential campaign.

The idea is simple, the ambition extraordinary: Trump wants to protect all US territory against any type of air attack – by aircraft, drone, or missile – regardless of the country of origin. That means possible attacks by Russia or China are included in this calculus. Admittedly, it is difficult to distinguish new initiatives from existing programs. However, the administration has already taken a series of legal, administrative, and financial measures intended to contribute to the establishment of Golden Dome. According to the White House, the project will cost US$175 billion and be completed by the end of Trump’s second term (in 2029).

Although much remains unclear, it is certain that the system will consist of multiple layers on land, at sea, and in space, including space-based sensors and interceptor systems. But because the defense against long-range ballistic missiles remains the most controversial part of the initiative, it is the central focus of this analysis.

Efforts, limits, and objectives

Different types of missiles require different defense systems. For this reason, distinctions are crucial. Ballistic missiles differ in terms of launch platform, payload, and range. All defense systems consist of multiple layers to counter threats from missiles with different ranges, speeds, and flight paths.

Washington regards short- and medium-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs and MRBMs) as tactical weapons in regional conflicts because they are able to pose a threat to the forces or allies of the US but not to US territory itself. Only intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with ranges of several thousand kilometers are considered a strategic threat to US territory.

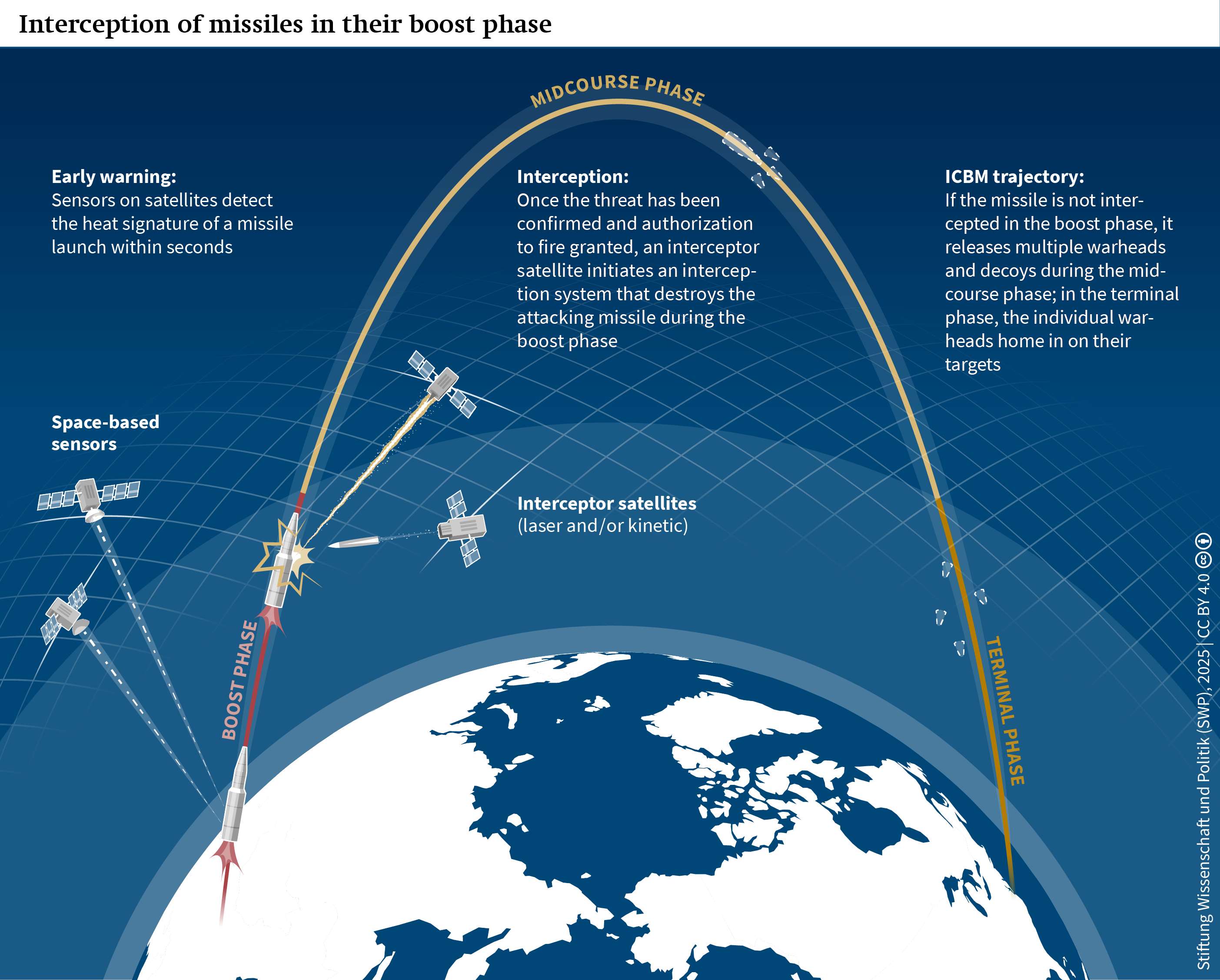

All ballistic missiles pass through three phases of flight. In the boost phase, which is over in just three to four minutes, a rocket lifts the missile into space. In the midcourse phase, which lasts around 20 minutes, the warheads travel along a ballistic trajectory under the sole influence of gravity. In the terminal phase, the warheads, having separated from the missile, re-enter the atmosphere and typically reach their targets in less than a minute. Defending against long-range ballistic missiles is extremely difficult in all three phases of flight.

Defense systems use different approaches to neutralize weapons in each flight phase. In the very short terminal phase, a warhead can be stopped only by interceptor systems that are stationed in the immediate vicinity of the target. This approach can protect key sites, such as military bases; however, an enormous number of systems would be required to defend a large country like the United States using this particular approach. For this reason, the technological focus has long been on the midcourse phase, in which more time is available to locate and engage the target.

Because of its fear of fueling global instability, the US government has in the past deliberately curbed the development of missile defense systems and relied primarily on deterrence to prevent strategic competitors from using long-range nuclear missiles. Over the past three decades, however, limited missile defense capabilities have been developed to respond to the threat posed by revisionist, isolated, and destabilizing states – North Korea at present and possibly Iran in the future. This course of action has been based on the assumption that such actors cannot be deterred by the threat of retaliation, which is why the United States must be able to fend off attacks.

The currently deployed Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which is intended to intercept missiles in the crucial, second phase of flight, was designed precisely for such threats. But even though the US system focuses primarily on defending against North Korean ICBMs, its effectiveness remains doubtful. In addition, breakthroughs in the development of such midcourse defenses are unlikely in the short term. For this reason, US officials concede that investments in and the expansion of the current system will not be sufficient to intercept Russian or Chinese missiles.

There are decisive advantages to intercepting missiles during the boost phase. It is in this phase that the missile is most vulnerable since countermeasures – such as multiple maneuverable warheads, decoys, and electronic jammers – typically come into play only during the midcourse phase. But because the boost phase lasts just three to four minutes, there is extreme time pressure. This means that ground-based interceptors would have to be positioned very close to the launch site – something that is not possible in the case of covering large countries like Russia and China or the world’s oceans. In theory, the problem could be solved with interceptor missiles in low Earth orbit (about 2,000 kilometers from the launch site). However, space-based interceptors would not remain stationary over a target but would circle in orbit; therefore, large satellite constellations – some for launch detection, others to carry kinetic or non-kinetic (e.g., laser) interceptor weapons – would be required to ensure seamless coverage.

This is where the main focus of missile defense within the Golden Dome initiative is to be found. Independent experts argue that for successful deployment, major advances in sensor coverage, battle management, and interceptor reliability are necessary, not to mention unprecedented investments in infrastructure. For its part, the US government claims that most of the required technologies already exist but warns that realizing the necessary “system of systems” will be challenging. The expertise of different agencies and the armed forces will need to be pooled, silo thinking overcome, and an integrated architecture created, US officials argue.

Trump’s unattainable goals

Historically, Washington has deliberately preserved a degree of ambiguity in its missile defense policy in order to keep adversaries uncertain about the scope and objectives of its programs. By contrast, the Trump administration has set concrete targets for capabilities, budgets, and timelines. However, Golden Dome is highly unlikely to achieve its stated goals.

Technology. The sweeping ambition of Golden Dome – namely, to defend the United States against attacks from all directions – increases the likelihood of failure. A comparison with its historical predecessor, which also envisioned space-based interceptors, is hardly encouraging. In the 1980s, the Ronald Reagan administration pursued the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), or “Star Wars,” which had the far more modest goal of intercepting just one third to one half of potential incoming Soviet missiles. After around US$80 billion had been spent, the project was deemed technically unfeasible and abandoned without any interceptor missiles having been deployed in space.

Even if there were technological breakthroughs, the laws of physics would stand in the way of building a Golden Dome. Key components, such as boost-phase intercept systems and space-based weapons, have not yet been tested; and it is completely unclear if and when they would become operational. Even if commercial providers were able to launch satellites even more cheaply and efficiently than they are already able to do, Golden Dome would require massive constellations to locate and destroy missiles. To illustrate: the system has only a few minutes in which to detect a launch, confirm it as a real threat, and direct a space-based unit to intercept – an enormous challenge in terms of data processing alone. Once this brief window has passed, the next satellite would have to carry out the actual interception. As a result, numerous satellites would be needed to destroy a single missile. Russia has around 500 launchers that could deliver nuclear warheads to the United States. Trump’s goal of reliably intercepting hundreds or even a thousand or more Russian and Chinese missiles would likely require tens of thousands of satellites.

Even if such a system were to be deployed, adversaries could try to overload it, destroy it, and possibly deceive it. At least in terms of cost, potential attackers will continue to have an advantage over defenders. Offensive measures are likely to remain far cheaper than defensive systems. This will force Washington to invest disproportionately more simply to keep up.

Adversaries are well prepared to render US defense investments ineffective. China is already increasing the number of its missile silos, while Russia is investing heavily in new strategic weapons designed to circumvent missile defenses. These include an intercontinental nuclear torpedo and a long-range missile capable of circling the globe to strike the United States from an unexpected direction. Overall, the pace of development – especially in China – suggests that only fundamental technological breakthroughs would allow the US to build defenses that cannot be circumvented by much cheaper offensive systems. This would include space-based systems capable of tracking the trajectories of extremely maneuverable weapons.

The same imbalance applies to space. While Tehran and Pyongyang have only limited space situational awareness capabilities, Beijing and especially Moscow possess highly advanced such capabilities. At the same time, China and Russia have demonstrated that they can destroy satellites in low Earth orbit, where space-based interceptors would likely be deployed. In addition to using kinetic means, Russia and China are developing non-kinetic counterspace capabilities, such as jammers, cyber capabilities, and directed energy weapons. Moreover, there are indications that Russia might be able and willing to deploy a nuclear weapon in space, allowing it to destroy a large number of US space assets all at once. However, it is worth noting that such radical countermeasures would impose high costs on every nation that depends on space, including Russia.

As Golden Dome technologies advance, Russia and China could develop further countermeasures to circumvent the new defense systems. The boost phase leaves little room for traditional decoys, but potential attackers could try to make that phase even shorter in order to reduce the defenders’ window of opportunity. They could also seek to limit the infrared signature of their missile exhaust or to launch from unexpected locations to complicate US early warning efforts. Powerful US missile defense systems would also likely prompt adversaries to invest in new technologies – such as novel propulsion systems, stealthier launch methods, and electronic or cyber-enabled countermeasures.

Costs. The current official cost estimate for building Golden Dome – US$175 billion – is almost certainly unrealistic. Taking into account expenditures on past such projects and the expected costs of key components, the total bill of a fully developed Golden Dome will undoubtedly be much higher. Some estimates put the price tag at more than US$500 billion, others higher still. Even if private-sector efforts were to make unexpectedly significant gains in speed, innovation, and efficiency, it is still extremely unlikely that the funding gap could be closed. The administration appears aware of this discrepancy: in the summer of 2025, the Pentagon’s Missile Defense Agency submitted a contract proposal worth US$151 billion that would cover only a fraction of the overall project.

Even a simple analysis makes clear the lack of credibility surrounding the official financial estimate. Each satellite in low Earth orbit has to be replaced every three to five years. This means that at least one-fifth of the constellation must be renewed annually. For a Golden Dome system with 10,000 satellites, that would mean 2,000 replacement satellites per year. Even if interceptors were mass-produced and far cheaper than today, they would likely still cost several million dollars apiece. Analysts estimate the required spending at about US$20 million per interceptor. Thus, US$40 billion would be required annually just to maintain the constellation – not including operating costs. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that ballistic missile defense is just one of many components that Trump is trying to bundle under the Golden Dome initiative.

Timeline. It is extremely unrealistic that Trump’s ambitious plan can be fully implemented by 2029. For one thing, many key technologies are likely still needed and their development would take decades or at least be subject to a highly unpredictable timeline. Even if Golden Dome required that only existing technologies be integrated, no military or civilian government program in peacetime has ever achieved such a complex integration within such a short timeframe.

The Trump administration – its habitual overconfidence notwithstanding – appears to have recognized that more time is needed. The Pentagon seems to be prioritizing the integration of data and sensor networks before tackling the ability to deploy space-based weapons. The first step is to build a satellite constellation for missile tracking, but even this is unlikely to be achievable before the end of 2029. In fact, the Pentagon’s own implementation plan assumes that by the end of 2028, it will only be possible to carry out a controlled demonstration under ideal conditions.

Gradual progress

Even if the Trump administration is unlikely to fully realize its Golden Dome vision, current plans and investments suggest the United States will make gradual progress in missile defense over the coming years – including in space, where sensors and data integration will play a central role. This gradual progress will be driven largely by various stakeholders that support advances in missile defense. The momentum appears to stem from a combination of military requirements, strategic considerations, political incentives, and the conflicting impulses of the US president himself.

Changes in the threat environment have increased the military need to strengthen missile defense. Above all, great power relations have deteriorated, fueling the risk of the nuclear threshold being crossed. Both Russia and China have invested in capabilities aimed not only at constraining US power projection but also at escalating a conflict beyond the level Washington appears prepared to accept in order to deter the United States from intervening in the event of a regional contingency. In addition, technological advances have made missile defense significantly more difficult: precision guidance has become ubiquitous, and novel flight profiles are able to bypass existing defense systems and potentially render them obsolete.

Strategic considerations are driving the expansion of missile defense, too. Some observers view missile defense as a tool within the US counterforce strategy that limits the scope for adversary retaliation after a possible US first strike and thus supports damage limitation while strengthening deterrence and reassurance. Others doubt that Golden Dome can be implemented but regard the project as an opportunity for larger US investments in advanced technologies that will push China and Russia into a long-term strategic competition that is to their disadvantage. Still others see investments in missile defense as leverage that could put Washington in a better position in future arms control negotiations with Beijing and Moscow.

Another major factor is likely to be political incentives. Missile defense appeals to different camps: isolationists see it as a path to self-sufficiency, hardliners as a tool of global power projection. For Trump and his allies, Golden Dome is driven more by political symbolism than strategic calculation (not unlike the plans for a wall along the Mexican border). The initiative is meant to demonstrate sovereignty and strength. This focus on visibility, however, could lead to unrealistic development or deployment decisions, since complex systems with long timelines are unlikely to satisfy a president who prioritizes public perception over concrete results.

Finally, Trump’s push for Golden Dome appears to be shaped by his own idiosyncrasies. The US president’s stance on nuclear weapons and military spending is contradictory. On the one hand, he calls for disarmament and retrenchment from global commitments; on the other, he insists on US military dominance, even while simultaneously undermining the foundations of American power. Just as Reagan’s unease about nuclear weapons led to SDI, so Trump does not want to rely on nuclear retaliation and prefers the politically expedient solution in the form of defense systems. Moreover, his faith in private-sector innovation reflects the belief that American technology can solve strategic problems – a facile conclusion that allows him to sidestep the core trade-offs as regards global commitments, broad alliances, and nuclear deterrence.

No open confrontation

Even if, ultimately, Trump’s ambitious Golden Dome vision is realized in rudimentary form only, there will still be substantial resources flowing into the expansion of US missile defense. This means that Germany and Europe will have some serious weighing up to do. And because of the huge uncertainty surrounding the initiative, it will remain difficult to draw clear-cut conclusions.

Potential advantages include advances in US missile defense that could strengthen US reassurance of allies. A scenario often cited is a limited NATO–Russia conflict in which Moscow threatens a small nuclear strike on the US homeland to deter Washington from defending Europe. In principle, more capable US missile defenses could render such coercive threats less credible.

At the same time, increased investments in missile defense could drive technological innovation in other critical areas, such as space-based sensors. This could give the United States an edge over China and Russia and further enhance its ability to reassure Europe. Expected US investments in space-based early-warning and tracking systems could improve NATO missile defense by enabling earlier and more precise target designation and thus increasing the chances of success for European interceptors. However, robust and rapid data sharing would be required, as well as release arrangements.

Regardless of the project’s actual success, increased investments in missile defense could put Russia under pressure to divert its own resources into countermeasures. Given Russia’s strained defense budget, overstretched industrial capacity, and pressing manpower demands, such pressure could potentially limit Moscow’s ability to rebuild its forces and credibly prepare for a conflict with NATO. Domestically, shifting more funds from civilian to military purposes could worsen the socioeconomic burden. Even though Russia has so far managed to expand its armed forces despite external pressure, this additional strain could contribute to greater European security and, in the longer term, create space for diplomatic efforts.

Golden Dome may also have tangible benefits for Europe’s missile defense, especially if major technological breakthroughs are achieved in the United States. Moreover, Europe could profit from subcontracts for the project; European expertise could be built in this way and thereby help accelerate the continent’s own missile defense efforts. Also conceivable is that existing European systems would become part of US infrastructure. And a more modest but concrete benefit for Europe could be reduced fragmentation: if interoperability were prioritized and duplication avoided, US initiatives might encourage more coherent planning across European missile defense projects.

However, alongside these potential advantages, the possible drawbacks must be noted. They include the risk that spending on missile defense diverts funds from areas that are crucial for Europe and NATO, such as the readiness of conventional forces and the military presence on NATO’s eastern flank. Indeed, the development of the costly Golden Dome could come at the expense of more reliable capabilities.

Furthermore, advances in missile defense could undermine strategic stability, especially in times of crisis. If a state believes that its nuclear forces could soon be neutralized by a preemptive strike and that it can no longer rely on its second-strike capability, the incentive to make a first strike increases. But the two claims often made in the debate about strategic stability cannot both be correct: either US defenses become effective enough to call Russia’s second-strike capability into question or relatively simple and cheap countermeasures suffice to circumvent those defenses, in which case their impact on strategic stability remains limited.

Moreover, the US government’s open pursuit of nuclear invulnerability through missile defense systems risks casting doubt on the diplomatic credibility of its Western allies. At international fora, Western allies present themselves as responsible nuclear actors committed to preserving the existing nuclear order – in contrast with the revisionist and destructive behavior of Beijing and, in particular, Moscow. But this posture is harder to maintain if Washington appears willing to employ space-based systems for its own protection and thereby seeks to undermine the deterrent capabilities of other states; and it becomes even harder if US allies themselves support this stance.

Finally, Washington’s plans could make it easier, above all, for China and Russia to justify their planned asymmetric capabilities in this area and further develop existing programs. In particular, the focus on space-based missile defense could serve as a pretext for those two states to deploy or invest more in space-based weapons. Moreover, interceptors in space increase the risk of miscalculating in space operations. But it is the vulnerability of satellite systems in orbit that poses the greatest danger: attacks on space objects can trigger a cascade of fragmentation and destruction in which the debris threatens the military and civilian infrastructure on which modern societies increasingly depend.

For Europe, it is the potential disadvantages of Golden Dome and the risks posed by the project that predominate, while the benefits remain uncertain. Thus, Europeans have an interest in ensuring that transatlantic relations are burdened as little as possible by the project. However, they are able to exert only limited influence on the Trump administration’s missile defense agenda. So far, the White House has paid little attention to European positions. Moreover, the technologies underlying the project are being developed mainly in the United States, so Washington is unlikely to see much reason to involve Europe. And because arms control with Russia and China has stalled, Europe lacks the diplomatic channels to help shape the process or advance cooperative solutions.

To make the best possible use of its limited room for maneuver, Europe should act in unity and, above all, avoid positioning itself as an obstacle to US innovation. Rather, it should present itself as a partner committed to the responsible and strategically sound development of missile defenses. While Europe may lack direct diplomatic levers, its position will be strengthened if it continues to plan and expand its own missile defense and early warning systems. A stronger negotiating position achieved in this way will increase Europe’s chances of being taken seriously by the Trump administration. At the same time, European technological breakthroughs could be channeled into Golden Dome, which would further increase the continent’s negotiating room. Europe should not publicly oppose the Trump administration’s plans; instead, it should voice its concerns behind closed doors, highlighting the fragility of space and the risk of unintended consequences. Germany, for its part, should continue its diplomatic efforts to promote responsible behavior in space, including within the framework of the United Nations.

Dr Liviu Horovitz and Juliana Süß are researchers in SWP’s International Security Research Division. This Comment was produced within the framework of the Strategic Threat Analysis and Nuclear (Dis‑)Order (STAND) project.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C50

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 50/2025)