The Transformation of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army into a ‘World-class Military’

Progress and Challenges on the Way to Achieving Joint Operations Capabilities

SWP Research Paper 2025/RP 03, 12.09.2025, 33 Seitendoi:10.18449/2025RP03

ForschungsgebieteDr Christian Wirth is a Senior Associate in SWP’s Asia Research Division.

The author would like to thank Clara Hörning for the research assistance.

Editorial deadline was May 2025.

-

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been undergoing fundamental structural reform aimed at improving operational preparedness and combat capability.

-

The imperative of a military loyal to the Communist Party dominates China’s defence policy and permeates the PLA’s organisational culture.

-

The centralisation of decision-making power in the hands of the chairman of the Central Military Commission, Xi Jinping, and his insistence on strict Party discipline run counter to a mission command model, as prescribed by the military doctrine.

-

Joint operations capabilities require intensified training and cannot be achieved until there has been a generational change among the commanders.

-

The PLA’s structures and decision-making processes remain opaque. They encourage groupthink and significantly hinder information exchange with external actors.

-

Amid the growing perception in Europe of threats from China, direct engagement with the PLA is becoming more important. Besides formal meetings with the Ministry of Defence and the Central Military Commission, the chiefs of the German and other European armed forces should promote the active and strategic use of more informal formats.

Table of contents

2 The Reform of the People’s Liberation Army

2.1 Technological progress, structural problems

3 Civil-Military Relations in the One-party State

3.1 Depoliticisation under Mao Zedong’s successors

3.2 Repoliticisation under Xi Jinping

3.3 Xi’s anti-corruption campaign

4 Military Theory, Strategy and Doctrine

4.1 Ideological guidelines and military theory

4.2 Military strategic guiding principles and military strategy

4.3 Military doctrine and operational concepts

5 Implementation at the Military-strategic Level

5.1 Central Military Commission

5.2 Aerospace, Cyberspace and Information Support Forces

5.3 Joint Logistics Support Force

5.4 Military training and career planning

6 Implementation at the Operational and Tactical Levels

6.2 Brigadisation of combat troops

Issues and Recommendations

By the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, which will be celebrated in 2049, the Communist Party of China (CPC) aims to restore the nation to prosperity and internationally recognised greatness. This mission, referred to in the Party rhetoric as the “Chinese dream” or “national rejuvenation”, puts the spotlight on the disputed status of Taiwan. At the same time, it turns conflicts over maritime zones in the East and South China Seas and the demarcation of the border with India into pressing security issues. The CPC considers these areas on the periphery of China to be integral parts of national territory that was once divided by colonial powers and must now be reunified.

Accordingly, the path towards national rejuvenation includes intensified efforts to transform the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a “world-class military”. To fulfil this “Chinese military dream”, as Chairman Xi has called it, the PLA must leave behind its past as a mass army focused on territorial defence. Fundamental reforms implemented since 2015 are aimed at enabling the PLA to prevail in high-intensity conflicts on China’s periphery. Although the primary task of the PLA – as the army of the Party, not of the state – is still to secure CPC rule, it is also expected to help assert Chinese interests in an increasingly multipolar world.

The key question, therefore, is to what extent the PLA has been enabled to win a war against a peer competitor outside China’s current borders. This is a question that is also of interest to decision-makers in Europe. As a proponent of a global order based on international law and as an ally of the United States, Germany is increasingly affected by escalating tensions in Asia. At stake is more than just German-Chinese economic ties, which would be at risk from any armed conflicts along China’s periphery. Beyond the issue of the Sino-Russian partnership, threat perceptions in Europe are being shaped by Germany’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific and NATO’s cooperation with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Moreover, the US regards China as the global threat, towards which all foreign and security policy must be oriented. Washington is meeting this challenge through comprehensive national (whole of government) and international (integrated deterrence) strategies of containment. Thus, the security situation surrounding China inevitably determines Germany’s room for manoeuvre in economic, foreign and security policy.

Against this background, the main research question to be addressed is how successful China has been in its efforts to enable the PLA to conduct what it calls “integrated joint operations” (Chinese: yiti hua lianhe zuozhan). While a final assessment of the PLA’s operational effectiveness is possible only in the wake of an actual conflict, an evaluation of the most recent reforms – combined with a systematic analysis of institutional changes – can offer valuable insights into the current state of the PLA. To this end, the first section of this research paper provides an overview of recent reform efforts and puts them in historical context. There follows an analysis of how the intertwining of politics and the military in the one-party state influences the PLA leadership. The next section provides an outline of the theoretical and doctrinal foundations of military operations, which leads to the subsequent examination of the reform of the command structure and military formations of the PLA. The final section analyses Chinese-language media coverage of PLA exercises.

Since the Chinese armed forces have no combat experience of 21st century warfare and as decision-making processes within the government remain notoriously opaque, the main research question can be addressed only in an approximate way. Numerous key documents remain classified, and Chinese analyses and media reports must be understood, above all, as means of communicating with or on behalf of the CPC leadership. Thus, this research paper applies a methodology that is established in the field of PLA studies: the evaluation of authoritative and semi-authoritative sources is supplemented by an examination of doctrinal debates and observable developments at the operational level. It also reviews the current state of research in these areas.

The analysis shows that the imperative of a unified Party leadership that can count on the loyalty of the military command continues to shape China’s defence policy and permeates the organisational culture of the PLA, even after what have been largely successful reforms. This imperative demands an extreme centralisation of decision-making power in the hands of the chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), namely, Xi Jinping. The resulting de facto delegation of responsibility upward across all levels of the hierarchy poses a major obstacle to the intended shift towards a mission command model. Despite significant progress, the overarching goal of integrated joint operations cannot be achieved until a new generation of commanders – who will have career experience beyond their respective service branches – assumes senior leadership roles and has been trained at operational level by participating in large-scale exercises.

The implementation of historic reforms notwithstanding, decision-making processes within the PLA remain opaque, however: the army of the Party continues to be a closed system, even by Chinese standards. This fosters groupthink and significantly hinders effective information exchanges with the outside world. Amid the growing perception, also in in Europe, of threats from China, direct channels of communication with the PLA are becoming increasingly important, including for Germany. Besides pursuing formal contacts, efforts should be made to actively use informal exchange formats over the long term. Here the goal would be to understand the mindset and behaviour of the Chinese military leadership as well as to communicate – regularly and directly – Germany’s own assessments, threat perceptions and expectations.

The Reform of the People’s Liberation Army

More so than his predecessors, Xi Jinping, the Chinese president and general secretary of the CPC, has promoted the narrative of China’s resurgence, according to which the country is emerging from the “Century of Humiliation” to reclaim its former greatness under his and the Party’s guidance.1 On this path, the Party and the PLA are inextricably linked. However, the state of the army has long been a cause for concern.

Technological progress, structural problems

While significant progress was been made towards the modernisation of the PLA (among other things, a competitive arms industry had been developed and military training improved) in the 1990s and early 2000s, considerable doubts about the PLA’s operational effectiveness beyond parades and orchestrated manoeuvres remained. Even after CPC General Secretary Hu Jintao, in 2004, tasked the armed forces with two “new historical missions” – protecting China’s economic interests overseas and contributing to international peacekeeping missions – the historically entrenched dominance of the People’s Liberation Army Ground Force (PLAGF) within the Chinese military persisted.2 As a result, the PLA’s organizational culture continued to be shaped by the mindset of the ground forces and their focus on infantry-based territorial defence. At the same time, no progress was made towards reducing the structural inefficiencies and widespread corruption within the PLA. On the contrary, the PLA’s status as the army of the Party granted it what amounted to immunity to reforms of the state apparatus.3

The PLA’s status as the army of the Party granted it what amounted to immunity to reforms of the state apparatus.

Intense debates took place among Chinese analysts and within the military elite about the seemingly unsolvable problems and contradictions within the PLA. Many complaints were made about major discrepancies between the missions assigned to the armed forces and the equipment available to carry them out, while the competence of commanders to lead operations was openly called into question. In turn, these issues were repeatedly addressed in professional journals and official media outlets. The authors of such publications often used slogans such as: “two incompatibles”, “fundamental contradictions”, “two big gaps”, “three whethers”, “two inabilities” and “five incapables”.4 The shortcomings described as the “five incapables” were regarded as most serious. Commanders were deemed incapable of 1) making appropriate situational assessments, 2) correctly understanding directives from superior authorities, 3) making timely and clear decisions about operational leadership, 4) assembling and deploying troops fit for purpose and 5) dealing with unexpected situations.5 These glaring weaknesses could not be offset by the introduction of modern intelligence, command and weapons systems. Moreover, in times of crisis, the lack of confidence in its capabilities could undermine the military’s loyalty to the Party leadership. Thus, the PLA was not capable of carrying out joint operations across different service branches, as required by modern warfare. Clearly, the Leninist military model that formed the basis of the PLA had become woefully outdated.

Three core problems needed to be addressed.6 First, the four General Departments – administrative bodies reporting directly to CMC – had long been undermining the authority of the top Party and military leadership. Four silo-like, self-contained fiefdoms had emerged and each was presided over by a member of the CMC. Second, the PLAGF, thanks to its central role in establishing China as a modern state and its superiority in numbers, permeated all areas of the military. Unlike the other service branches, which had their own commands, the four General Departments and the administrations of the seven military regions served as the executive bodies of the PLAGF. Third, there was no permanent command organisation responsible for planning and directing operations at either the strategic or operational level. A mission-oriented command structure was to be established only in the event of war.

Despite acknowledging these issues, General Secretary Jiang Zemin (in office from 1989 to 2002) and his successor, Hu Jintao (from 2002 to 2012), lacked the political clout to push through structural reforms against the deeply entrenched vested interests within the PLA. All that changed in 2013.

Fundamental reforms

The son of a first-generation Party cadre with personalties to the PLA and the holder of an exceptionally powerful position within the CPC (more powerful than any since Deng Xiaoping), Xi Jinping has commanded – and continues to command – far greater authority than his predecessors. Under Xi’s leadership, the Party was able to push through a sweeping reform of the PLA. At the third plenary session of the 18th Party Congress in November 2013, a comprehensive reform agenda was adopted. Xi himself assumed the chair of the newly established “Leading Small Group on National Defence and Military Reform”;7 and in 2015–16, a series of reforms were announced.8 As stated during the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, these reforms constituted the first of three major steps towards building a “world-class military”9:

Step 1: By 2020, the ground forces were to become fully “mechanised”, that is, equipped with armoured vehicles; during the same period, advanced information technologies were to be introduced and strategic capabilities enhanced.

Step 2: By 2035, the modernisation of the military is to be completed.

Step 3: By 2049, the status of “world-class military” is to be achieved.

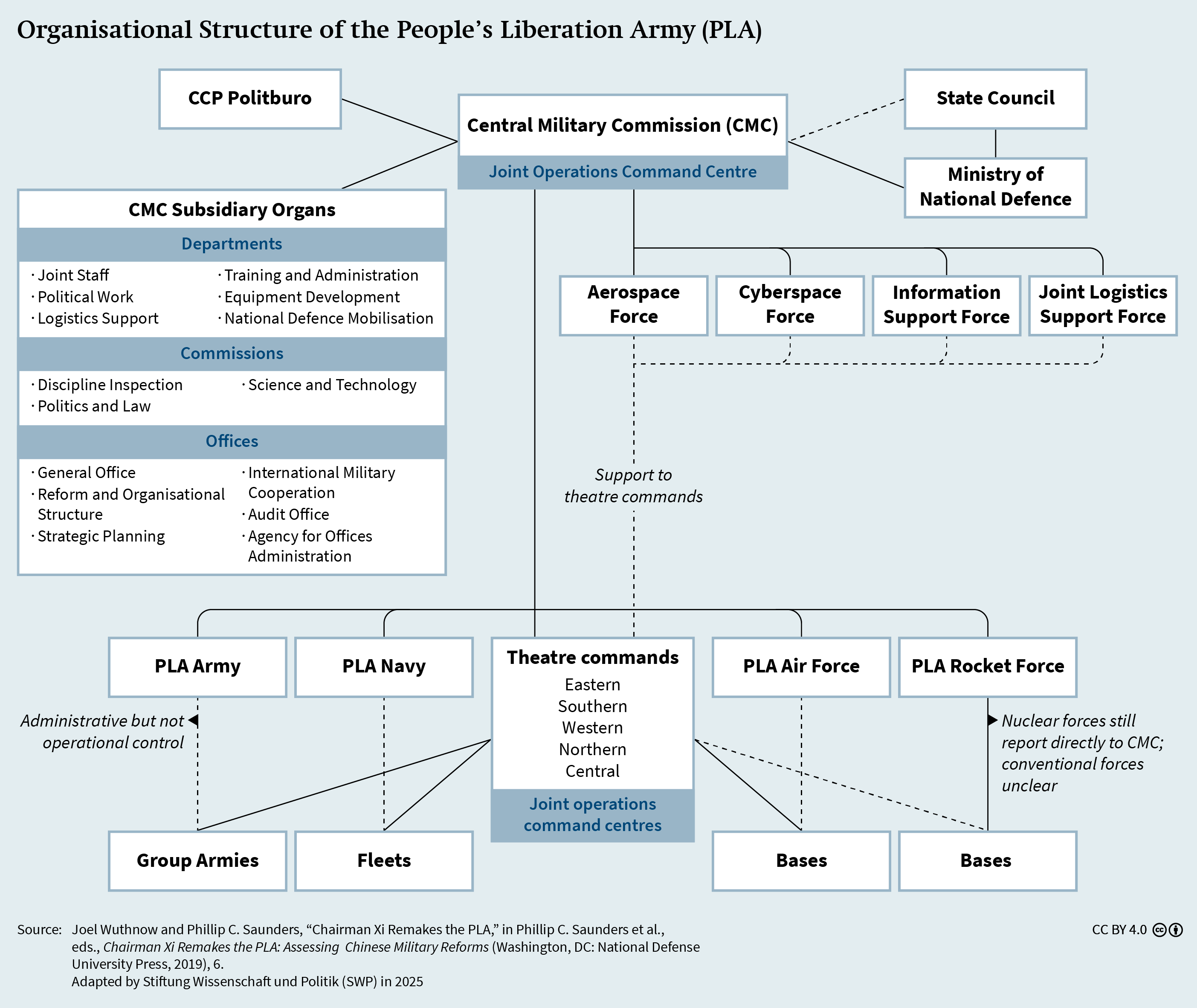

To enhance the PLA’s combat readiness, the first phase of the initial reforms (after 2015) – referred to as “above the neck” – fundamentally overhauled the top command structure (see Figure 1).10 The four General Departments were abolished and their functions consolidated within the CMC, whose operational planning and command capabilities were strengthened. At the same time, the seven military regions were replaced by five joint-service theatre commands (see Figure 2, p. 24), which, within their respective territorially defined areas of responsibility, have operational control over the troops of the PLAGF, the air force (PLAAF), the navy (PLAN) and the conventionally armed units of the rocket force (PLARF).

These reforms were accompanied by a stronger concentration of power within the CMC, whose members were reduced to seven, and not least in the hands of its chairman, General Secretary Xi. Therefore, understanding the relationship between the Party and the PLA and the way in which those ties have changed is essential to grasp how the reforms were designed and implemented.

Civil-Military Relations in the One-party State

Following its victory over the rival nationalists of the Kuomintang in 1949, the PLA was instrumental in establishing the CPC at the apex of the modern state. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) and the Tiananmen protests (1989), the PLA protected the Party from any loss of power. Thus, there is a symbiotic relationship between the state, the Party and the PLA.12

Depoliticisation under Mao Zedong’s successors

When, from the late 1970s onwards, Deng Xiaoping prioritised economic development and the opening up of the country, the PLA’s significance declined. Although national defence was one of the pillars of Deng’s “Four Modernisations”, the military was chronically underfunded – despite the number of troops having been cut by 1 million – and had to start generating money. As alternative sources of revenue, the PLA engaged in agriculture and also became involved in running transportation enterprises, hotels, mining companies and industrial firms.

The role of the military leadership in the power struggles within the Party and the state diminished, too. As a former comrade of Mao and as a leader whose personal authority was rooted in the Communist resistance movement, Deng could rely on loyal wartime allies (from before 1949). Nevertheless, he used his power both to rein in reformers like General Secretary Hu Yaobang and Prime Minister Zhao Ziyang and to suppress protest movements such as those in June 1989.

Similarly, Jiang Zemin, Deng’s successor, used his position as CMC chairman to limit the influence of his rival and eventual successor, Hu Jintao. However, on account of not having served in the PLA or had ties to Mao, neither Jiang nor Hu had the authority to discipline the PLA. Despite their institutionally guaranteed pre-eminence, they still had to court the loyalty of the generals. This was achieved through regular visits to the troops and other demonstrations of honour, the unquestioning approval of their promotion proposals and significant increases in wages and other benefits, as well as the boosting of defence spending. It was only after eight years as CMC chairman and a generational change within the commission that Jiang succeeded in reducing the troops by 500,000 and later by another 200,000.13 At the same time, he had become powerful enough to reject the demands made by some generals for retaliatory measures after the US had accidentally bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade in May 1999 and to delay the construction of aircraft carriers.14 Yet, the divestment from commercial activities initiated under Jiang was not completed until 2015.15 For his part, Hu was unable, even by the end of his second term, to make the further troop reductions necessary for improving efficiency or to reorganise the military regions.

Between 1989 and 2012, the demarcation between the PLA and the CPC became increasingly pronounced: the military had evolved into a bureaucratic actor focused primarily on technical and operational expertise.16 Unofficial contacts between civilian and military cadres became taboo.17 However, despite significant progress in developing new weapons systems and structural reforms aimed at strengthening the air force and navy, the more professionally organised PLA continued to suffer from institutional stagnation bordering on the inability to reform. Amid the growing domestic and security-related challenges, CPC elites grew increasingly alarmed by the lack of Party control over the military and the low combat effectiveness of the PLA.

Repoliticisation under Xi Jinping

Unlike his predecessors, Xi Jinping made the PLA his top priority. His proactive approach had the strategic goal of turning it into an independent power base for consolidating control over the Party. In this endeavour, Xi was able to benefit from his longstanding personal ties with senior generals such as Zhao Keshi and Zhang Youxia, the latter of whom had once served alongside Xi’s father. Initially, he also relied on officers with whom he had worked during his earlier leadership roles in the Fujian and Zhejiang provinces.18 Moreover, as the Party propaganda highlights, Xi spent three years after the completion of his studies working as a secretary at the CMC and therefore can be considered a veteran. His alleged closeness to the troops – as someone who leads not “from behind a desk” but from within the ranks – is also emphasised.19 Xi’s numerous appearances at parades in military-green or even camouflage uniform, where he can be seen riding in open vehicles and surrounded by soldiers, are meant to reinforce this image, as are his frequent visits to military headquarters. And the fact that his wife, who is one of China’s most famous singers, served in the PLA’s song and dance troupe for many years has further bolstered Xi’s image as a leader who is very close to, if not part of, the military.

To give Xi greater control over the PLA, the instruments of military oversight were strengthened. The Discipline Inspection Commission, the Audit Bureau and the Political and Legal Affairs Commission were all subordinated to the CMC. These bodies now provide additional oversight to that of the Political Work Department, which, through political commissars and Party committees, ensures that across all levels of the hierarchy – including the smallest military units – personnel management and political indoctrination conforms with the Party line.

The core dilemma for the Party is that while an effective military requires professionalisation, this inevitably increases the distance between the PLA and the CPC

Paradoxically, the extreme concentration of power in the hands of Xi has led to an even stronger demarcation between the Party and the military. Xi is the only official to be a member of both the CMC and the Politburo Standing Committee (there have been no military members of the Politburo Standing Committee since 1997). Even at key meetings convened to decide the future of the PLA, no permanent Politburo Standing Committee member – other than Xi – was present. Meanwhile, the National Party Congress has seen a decline in the number of PLA delegates, at a time it has lost influence more generally.20 Furthermore, political commissars, who once served as civilian overseers of Party discipline within the military, are now recruited from the PLA’s own ranks and have a military rather than civilian identity.21

This stronger demarcation became necessary in order to overcome the growing contradiction between the PLA’s domestic (revolutionary) and foreign-policy (military-strategic) missions.22 The core dilemma for the Party leadership remains the fact that while an effective and combat-ready military requires professionalisation, this very process inevitably leads to the undesirable distancing of the PLA from the Party.23 In the event of a crisis, that contradiction could rapidly become evident if parts of the PLA were to feel compelled to choose between loyalty to the Party (or a faction within it) or to the state and the people. In this context, it is important to note that the PLA has transformed itself from an army of the peasant-proletarian masses into one whose members are drawn largely from the urban middle class and, accordingly, are aware of their own interests.24

Thus, the Party leadership is faced with a perennial challenge. On the one hand, it has to instil into the PLA the political awareness that the military must serve as a bulwark for the CPC chairman against intra-party rivals and against societal dissent. On the other hand, the Party has to prevent the PLA from becoming overly politicised and possibly interfering in civilian decision-making or even taking sides in intra-party power struggles. The previous approach – whereby the PLA leadership enjoyed considerable autonomy and the Party sought to maintain its loyalty through generous employment conditions and the acquisition of new high-tech “toys” – failed to boost either political reliability or combat readiness. As in the case of the broader reforms of the Party and the state, Xi and his supporters became convinced that intensified ideological indoctrination, together with a harsh crackdown on disobedient soldiers, would strengthen the PLA’s loyalty to the Party.25 The PLA was to be disciplined through a strict focus on achieving combat readiness – that is, on the ability to “fight and win” military conflicts.26

Xi’s anti-corruption campaign

The fact that the anti-corruption campaign was extended from the Party to the PLA testifies to Xi’s vast powers. The most radical initial measure was the prosecution of General Xu Caihou and General Guo Boxiong, who had recently retired from their positions as CMC Vice Chairmen, in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Originally elevated to the most senior military position by Jiang Zemin, the two generals had steered the PLA’s course largely unchecked, especially during Hu Jintao’s 10-year tenure. The organisational culture fostered by them included the widespread buying and selling of promotions at all levels of the officer corps. Moreover, Xu, as head of the disciplinary inspection body, had refused to initiate investigations even when ordered to do so by General Secretary Hu – a particularly serious transgression.27 Xi saw the state of affairs in the PLA as a threat not only to his own authority but to the rule of the Party as a whole. He repeatedly cited the cautionary tale of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, whose downfall he attributed in part to the Red Army’s lack of loyalty.28 Accordingly, more than 80 active generals, lieutenant generals, and major generals were disciplined and expelled from both the PLA and the Party between 2012 and 2014.29 It is thought that thousands of lower-ranking officers were affected, too. At the same time, Xi introduced numerous new regulations aimed at tightening oversight of the political commissars in particular, a group that, ironically, appears to be especially susceptible to corruption.30

Because corrupt practices were so widespread within the PLA as to leave hardly any officer immune, the prosecution of certain individuals rather than others could not but be seen as politically motivated. With the sword of disciplinary action now hanging over many powerful officials, Xi sought to extract personal loyalty from his generals. In November 2014, he got together more than 420 top PLA officials for a Political Work Conference that resembled the “self-purification rituals” of earlier times.31 The choice of location – Gutian – was highly symbolic: it was there that, in 1929, Mao Zedong first swore the officer corps to loyalty to the Party, laying the foundation for CPC-PLA ties. Xi began the meeting by criticising the unresolved problems among “leading cadres” regarding ideology, political awareness and work ethic. He warned that the military was becoming too influenced by the supposed exemplary model of depoliticised Western armies. To address these issues, he outlined five remedies32:

-

Strengthening the military’s ideological conviction of the primacy of the Party over the PLA;

-

Recruiting and promoting reliable and capable individuals;

-

Fighting corruption as a long-term mission essential to the Party’s survival;

-

Mastering modern warfare; and

-

Reviving political work within the ranks.

This moral sermonising was immediately followed by public pledges of loyalty from various generals in the form of lavish praise of Chairman Xi – statements that were reminiscent of the Mao era.33

Despite a long anti-corruption campaign, the same problems persist

Even after more than a decade of Xi’s direct control over the promotion of senior officers and despite what has been a long anti-corruption campaign, the same problems persist. By the end of 2024, two consecutive defence ministers and the director of the Political Work Department, all three of whom had been members of the CMC, along with the entire, with China’s nuclear arms entrusted leadership of the PLARF, and a number of other generals, lieutenant generals and major generals had disappeared from public view.34 In parallel with these dismissals, Xi repeatedly lamented the “lack of discipline” among PLA cadres and expressed deep distrust towards the military leadership. Thus, it came as no surprise when, in June 2024, he convened another Political Work Conference focused on the PLA’s loyalty to the Party. Like 10 years earlier, he chose an historically symbolic city – this time Yan’an – as the venue. It was there that Mao Zedong had consolidated his control over the Party through a series of “rectification campaigns” between 1941 and 1944.35 Just like back then, the question arises whether political disloyalty is not the main concern and problem that needs to be addressed36 How does the recalibrated relationship between the Party and the PLA affect military effectiveness?

To assess how the dilemma known as “Red (ideological, Communist) versus Expert” may impact military operations, it is necessary to be familiar with the Chinese conception of modern conflict and the anticipated kind of warfare.

Military Theory, Strategy and Doctrine

At the top of the hierarchy of perspectives and concepts related to war and defence is the military theory of the respective CPC leadership. The military strategy, including the strategic guiding principles of the CMC, comes in second place, followed by the operational concepts; the latter, which dictate how the PLA is to achieve its war objectives, are being continuously developed by the PLA’s research institutes, primarily the Academy of Military Science. Before these three programmatic levels are examined in detail, the following should be emphasised: Since Xi Jinping’s rise to power, Chinese defence policy has been personalised to an extent not witnessed since Mao. This stands in diametric opposition to the principle of mission-oriented command, which is essential for military commanders at all levels to efficiently coordinate and swiftly execute operations.

Ideological guidelines and military theory

At the 19th Party Congress in November 2017, the CPC declared the term “New Era,” first introduced in 2013, to be a universal reference for the present.37 This definition of the third historical period – which follows the revolutionary era under Mao and the reform era under Deng, Jiang and Hu – endows Xi with a status approaching that of Mao and Deng. In May 2019, the Political Work Department of the CMC issued a guide to Xi’s “thought on strengthening the military”.38 Both CPC members and PLA personnel alike are required to engage in regular, intensive study of Xi’s ideological thinking.39 Depending on their positions, the indoctrination takes up 20–40 per cent of their working hours.40

Xi’s defence policy strongly emphasises “national rejuvenation” and the fulfillment of the “Chinese dream”, including through the transformation of China into a “strong maritime nation” or “maritime great power”.41 The intensified “strategic competition” with the US – which is seen as euphemism for the “comprehensive containment” and “suppression” of China by the US and its Western allies – has increased the urgency of achieving these goals.42 This Western strategy, according to the CPC, is adding fuel to “separatism” in Taiwan and territorial disputes on land and at sea.43 In response, the PLA’s “historical missions” have been adjusted to contribute to the achievement of the national goals.44

The 2015 White Paper on Defence identified the “resolute defence of the leadership of the CPC and the Socialist system” as the main mission of the PLA, while the protection of China’s “development interests” was mentioned alongside the need to defend the country’s sovereignty and security.45 The most recent White Paper on Defence, published in 2019, focuses more on the traditional military tasks. It sets out five guiding principles and defines seven missions for the PLA.46 The guiding principles are: 1) the resolute defence of China’s sovereignty, security and development interests; 2) the non-pursuit of hegemony, expansion or the establishment of spheres of influence; 3) the implementation of the military strategic guidelines for the “New Era”; 4) the continuation along the Chinese military’s path to modernization; and 5) the building of a “community with a shared future for humanity [or mankind]”. The missions derived from these guiding principles are:

-

To safeguard China’s national territorial sovereignty and its maritime rights and interests;

-

To maintain combat readiness;

-

To conduct military exercises under real combat conditions;

-

To safeguard interests in major security fields (such as nuclear deterrence, outer space and cyberspace);

-

To counter terrorism and maintain [internal] stability;

-

To protect China’s overseas interests; and

-

To participate in disaster rescue and relief.

Military strategic guiding principles and military strategy

The military strategic guiding principles encompass the core ideas of the military strategy.47 In Chinese publications, there is often no clear distinction made between these two terms. The most recent official documents on military strategy use the phrase “informationised local war” to describe the anticipated form of warfare. This refers to the changes that are being driven by the increasing use of information technologies and discussed worldwide as the “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA). Computer-assisted systems are no longer seen merely as supplementary but rather as decisive factors on the battlefield. This is because they 1) enable a more comprehensive and precise situational awareness to be established and disseminated much more quickly, 2) accelerate decision-making and command processes across all hierarchical levels, 3) allow for more efficient logistics management and 4) achieve weapon effects with much greater accuracy and speed over much longer distances. Most important, they do all of this in the cyber and space domains and with the help of unmanned platforms.48

A further advancement – towards “intelligentised” warfare, characterised by confrontations between algorithms rather than systems – has been discussed in China for some time, too. The 2019 White Paper on Defence mentions “intelligentised warfare” as a development that is “visible on the horizon”, while Xi himself repeatedly emphasized the need for an “integrated development of mechanisation, informatisation and intelligentisation”.49 Nevertheless, the term has not yet established itself as a programmatic formula.50 All the concepts mentioned here modify the two guiding principles of strategic defensive positioning (“Active Defence”) and the comprehensive mobilisation of the people for defence (“People’s War”), both of which date back to Mao.51

Because closer coordination between the service branches is essential, the term ‘integrated joint operations’ is used.

However, since operations under “informationised” conditions are conducted at a much faster speed and over increasingly greater distances, counter-attacks can no longer be launched only from the national border or from within the country itself. Thus, China’s 2015 White Paper on Defence makes the first mention of the army transitioning from “theatre defence” to “trans-theatre defence,” the navy being tasked not only with “offshore water defence” but also with “open seas protection” and the air force having to be prepared not only for defence but also for attack. The areas now regarded as war zones are predominantly maritime and require the capability to conduct operations jointly in all five domains (that is, land, sea, air, outer and cyber space). In November 2020, it was officially confirmed that the “Outline of Joint Operations of the People’s Liberation Army (Trial)” had gone into effect that same month.52 The document itself was not published, but the conceptual context and various official statements provide an indication of its contents.

Military doctrine and operational concepts

Since the Second Gulf War in 1991, military experts have regarded joint operations as the fundamental form of modern combat. Later, the NATO operation against Serbia in 1999 revealed that wars could be won not only by destroying enemy forces on the battlefield but also by disabling the adversary’s “operational systems”. Today, with the geographically defined battlefield shrinking, the theatre of war is expanding to encompass all domains, including non-physical ones.53 Combat operations are no longer merely multi-domain but rather all-domain, which means they take place not only in military spheres but also in civilian and “cognitive” ones. Thus, from around 2004 onwards, China has referred to confrontations between systems: unlike the mechanised era, in which combat involved platform versus platform and force against force along one-directional lines of operations (that is, from the rear to the front and from outside to inside), modern warfare involves nonlinear operations conducted by various units from different service branches and with fluid transitions between war and peace and between defence and attack across all domains. Because the service branches must be coordinated even more closely and connected in real time, the PLA has referred since 2004 to “integrated joint operations”.54 The systems used for such operations are: 1) units from the platform and group-level upwards, 2) matrix-like structures connecting those units and 3) elements that provide sufficient capabilities of command and control, reconnaissance, firepower, information warfare, manoeuvrability, protection and support.55

To be able to control the speed and intensity of the conflict in this type of warfare and to prevent escalation beyond the desired level and a specific geographical area (“war control”), information dominance is considered essential. Joint operations are therefore designed for “system destruction warfare”, which aims to paralyse, control or destroy critical components of the enemy’s operational systems.56 This is a form of “target-centric warfare”.

A prerequisite for the successful conduct of such joint operations is the understanding that the classic hierarchical division into strategic, operational (Chinese zhanyi, which translates literally into “campaign”) and tactical levels becomes irrelevant. And this challenges the dominant position of the ground forces. Moreover, integrated joint warfare requires expertise and technical means that not only enable commanders at all levels to make rapid decisions but also increase the Party leadership’s control over these wider-ranging and faster-paced operations. For this reason, fundamental reforms had to begin with the PLA’s command and control structure.

Implementation at the Military-strategic Level

The blueprint for the reform of the PLA was unveiled by the CMC in early January 2016.57 Some 10 months later, at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, the “CMC Chairman Responsibility System” was codified in the Constitution of the CPC. Under that system, Xi Jinping has the authority to make all major decisions.58 At the same time, the membership of the CMC was reduced from eleven to seven: besides the civilian chairmanship held by the CPC general secretary, the retained posts were those of the two vice chairmen, the minister of defence and the directors of the Joint Staff Department and the Political Work Department, while the secretary of the Discipline Inspection Commission joined the body for the first time. Significantly, those who lost their posts were the commanders of the service branches and those responsible for logistics and procurement and development. The CMC saw major personnel changes, too,59 although PLAGF officers continue to hold the majority of posts.60 Moreover, as of summer 2025, there is still no civilian vice chairman – a position that, in keeping with tradition, would be occupied by a possible designated successor to Xi and would help consolidate the former’s authority within the Party, the state and the PLA.

Central Military Commission

In order to accelerate the transformation of the PLA into a “world-class military” and enable it to plan and execute joint operations, the CMC required a comprehensive institutional apparatus. The concentration of decision-making authority in the hands of the CMC chairman is a striking feature of that apparatus: while the military chain of command, starting with Xi as commander-in-chief, runs directly from the Joint Operations Command Centre (JOCC) to the joint operations centres (JOCs) of the theatre commands, it is Xi, in his capacity as chairman of the CMC, who presides over 14 subordinate agencies.61

At the core of the CMC is the General Office, which is responsible for the internal organisation of the commission and, as the chairman’s eyes and ears, monitors compliance with his directives. The heads of the Discipline Inspection Commission, the Political and Legal Affairs Commission and the Audit Bureau all report directly to this office.

The second-most important organisational unit is the Joint Staff Department, which is responsible for command and control, operational planning, military strategy, organising joint training among the service branches, assessing combat capabilities and ensuring operational readiness. The Political Work Department is the highest authority within the PLA to handle personnel administration and political education – that is, internal and external propaganda for the CPC. Through its subordinate political work departments, political commissars, Party committees and Party cells, that permeate the hierarchy down to the lowest level, this body ensures the “absolute leadership” of the CPC over the PLA.62 The Logistics Support Department sets standards, engages in financial planning and resource management and oversees real estate management. The Equipment Development Department has oversight over procurement projects and conducts related research, development and testing procedures. The Training and Administration Department is responsible for the training of professional soldiers and is thought to handle the planning and implementation of training exercises as well. And the Defence Mobilisation Department oversees the reserve formations, including the administration of the military districts.

The Discipline Inspection Commission enforces Party discipline within the PLA through the investigation of cases of corruption, disloyalty and other misconduct. The Political and Legal Affairs Commission is responsible for drafting and enforcing the laws and regulations that govern the PLA; it is the highest authority for military justice as well as for the military police. The Science and Technology Commission advises the CMC on weapons development and serves as a bridge for cooperation with the defence industry.

The Strategic Planning Office is tasked with developing in-depth strategic analyses, conducting studies on resource allocation and drawing up concepts for organisational reforms; however, responsibility for actively managing the reform process lies with the Reform and Organisation Office. The Office for International Military Cooperation oversees exchange programmes with foreign militaries and handles collaboration with international partners. The Audit Bureau is responsible for financial oversight. The Organ Affairs General Management Bureau deals with logistical functions related to personnel management and real estate administration; it is also tasked with the provision of welfare support to veterans, which, arguably, plays an important role in ensuring the acceptance of the reforms.63

Yet, the success of joint operations hinges on intelligence gathering and analysis, as well as on maintaining command and control across all levels. These tasks were initially assigned to the Strategic Support Force, created in December 2015 as a unit directly subordinate to the CMC at the start of the first phase of the military reform process.

Aerospace, Cyberspace and Information Support Forces

The creation of the Strategic Support Force marked a pivotal moment in the development of strategic thinking around “informationised warfare.64 The consolidation of capabilities for intelligence gathering, conducting operations in the space and cyberspace domains and processing information within the command structure is key to gaining the upper hand in a confrontation between systems. In April 2024 these responsibilities were divided between three newly created, hierarchically equivalent organisational entities: the Aerospace, Cyberspace and Information Support Forces, thereby confirming the assumption that the Strategic Support Force had served as a transitional structure only – one that facilitated the shift to the post-Leninist command architecture introduced with the reform.65

The Aerospace Force oversees the increasingly important tasks of satellite-based surveillance and reconnaissance as well as satellite-based navigation and targeting. It has eight bases, including three satellite launch centres and several control centres. The last-named maintain overseas facilities – for example, in Namibia, Pakistan and Argentina – and operate the Yuan Wang- and Liao Wang-class telemetry ships.66 The force is also responsible for the development of counterspace capabilities to disrupt and destroy enemy satellites. The Cyberspace Force is tasked with electronic, cyber and psychological warfare; until 2017, responsibility for this domain was spread across various departments and service branches.67 Its operations are targeted primarily against Taiwan.68 The Information Support Force manages the PLA’s command and control systems. It enables the CMC to lead operations through its JOCC and the communication brigades of the theatre commands down to the tactical level. The force thereby makes use of an integrated command platform, which also involves maintaining the National Defence Communication Network, a fibre-optic system that extends throughout the country.69

The establishment of the Aerospace, Cyberspace and Information Support Forces reflects the strategic thinking behind “informationised” warfare.

As the range of their responsibilities shows, these three organisational units form the backbone of the command structure. Accordingly, it is these “new-type combat forces” that have the greatest need for highly qualified personnel.70 Besides working with the universities that have close links to these units – the so-called “Seven Sons of National Defence” – the military and the defence industry are increasingly collaborating with other leading universities and private companies.71

Joint Logistics Support Force

Established in September 2016 as an organisational unit subordinated directly to the CMC, the Joint Logistics Support Force is the main body responsible for logistics support.72 Thus, in this area, too, the earlier centralisation efforts are being continued. Indeed, they are necessary owing to the significantly higher demands of joint operations, which have become high-intensity, fast-paced and nonlinear. Nonetheless, questions remain about how this new unit will ultimately function.

There are three organisational divisions within the logistics support system. The first covers essential supplies such as fuel, food, water, medical services and land transportation, which used to be provided by the individual service branches. Today, the Joint Logistics Support Base in Wuhan, a large city located at a key transportation hub of China, presides over five joint logistics support centres, which are located in Wuxi, Guilin, Xining, Shenyang and Zhengzhou; thus, each of the five theatre commands has one of these centres within its area of responsibility. The centres maintain extensive networks of warehouses, pipelines and medical facilities and oversee the joint logistics brigades, which are responsible for operational logistics.73

The second division covers logistics services specific to each service branch. These supply chains continue to be managed by the respective commands, which also have their own transport and maintenance capacities. But efforts have been made to streamline processes by consolidating logistics and equipment tasks into support departments.74 Among the most important functions of the service branches is the handling of overseas logistics. This applies, above all, to the navy, which has overall responsibility for overseas bases such as those in Djibouti (East Africa) and Ream in Cambodia.

The lack of a permanent organisation that has the authority to comprehensively manage logistics is seen as the main weakness.

The third division comprises the civilian component. To save costs and expand capacity, the PLA is increasingly making use of civilian service providers. Within larger companies, it maintains military representative offices with the aim of simplifying cooperation. To ensure such services can be accessed even during times of crisis, operational military standards must be defined and implemented – for example, for facilities at train stations and ports and for the protection of critical transport and traffic infrastructure.75 Furthermore, company employees require military training and organisational links to the PLA.

The design of these processes remains unclear even after the extensive debates among Chinese experts, however.76 The lack of a permanent organisation that has the authority to comprehensively manage logistics for the respective theatre commands is seen as the main weakness.77 In the event of a crisis, an ad hoc structure of joint transport and supply centres must first be established at all levels of the hierarchy.78 Moreover, owing to the focus on “local wars” and the absence of overseas bases, this system is not suited to the task of supporting combat units beyond China’s borders. Even the capacity to deploy troops for a potential invasion of Taiwan remains insufficient to this day.79

All in all, the PLA appears to suffer from the same problem as other armed forces: while recognised as one of the keys to success, logistics is often neglected in practice. That is why leadership positions in this area are less sought after. At the same time, the increasingly demanding nature of operations calls for more highly qualified and motivated personnel – or a “new type of military talent” – in this area, too.80

Military training and career planning

In order to address the shortage of well-trained soldiers, recruitment procedures have been adjusted and new career models developed. After completing their mandatory two-year service, conscripts are encouraged to commit to a career in the armed forces. The focus is on building a professional non-commissioned officer corps with specialisations in “administration” and “technical expertise”.81 Although China’s increasing economic difficulties are expected to help bolster efforts to hire better-trained personnel and although military wages remain competitive compared with the civilian labour market, many would-be professional soldiers appear to be put off by the living conditions in the PLA. Since the suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests in June 1989, military personnel are no longer stationed near the place where they were raised; on the contrary, they are often assigned to posts far from their relatives and in rural areas.82

The Party leadership has recognised that “jointness” is a mindset that requires appropriate training and socialisation.

It is also the case for officers who opt to follow career paths as commanders, staff officers or “specialised technicians”, with all the corresponding self-development opportunities, that the PLA still seems relatively unattractive. Being stationed far from their hometowns, unable to start their own families owing to limited leave, facing difficulties finding accommodation and, in the case of rural recruits, having to overcome the obstacle of obtaining permanent residence permits in urban areas – all this remains reality today. What is more, military personnel continue to have a relatively low social status, while it is very likely that the difficulty of combatting abuse in a highly opaque, hierarchical organisation like the PLA – and particularly under intense pressure to perform – does nothing to increase the appeal of a military career.83 In general, the organisational culture of the Chinese military is shaped by the need to build strong personal networks.84 And an efficient way to establish reliable connections is through the exchange of favours, which fosters corruption and fundamentally conflicts with a merit-based system.85

For this reason, the Party leadership is attempting to change the organisational culture of the PLA. It has recognised that “jointness” is a mindset that cannot be achieved simply by merging command structures and networking weapon systems; rather, it requires appropriate training and socialisation. Since 2016 efforts to this end, which are focused on the National Defence University (NDU), have been reinforced by four sets of measures.86 First, in addition to new teaching methods and courses on joint operations, a specialised training programme is now available at the NDU as part of the course for senior staff officers. Second, other training institutions subordinated to the CMC have expanded their joint operations leadership courses for staff officers down to the battalion level. Reportedly, completion of these programmes has become a prerequisite for being appointed to certain positions within the individual theatre commands. Third, the NDU has assumed the oversight of the operations of the newly established Joint Operations College in Shijiazhuang. And fourth, the service branch academies have similarly shifted their focus to joint operations leadership, partly by establishing exchange programmes with training institutions from other service branches. At the same time, they have strengthened cooperation among themselves as well as with the commanders and staff of operational units. Moreover, efforts have been under way since 2002 to improve the evaluation of training and leadership performance. The main relevant document here is an unpublished directive called the Outline of Military Training and Evaluation (OMTE).87

However, it is the implementation of reforms at both the operational and tactical levels that are crucial for the successful transformation of the PLA into a “world-class army” capable of conducting joint operations.

Implementation at the Operational and Tactical Levels

Theatre commands

Ultimately, the success of capability development hinges on the theatre commands (TCs – see Figure 2, p. 24),88 whose establishment is the reforms’ most visible result. While any scenario involving a “local war” would inevitably trigger the socio-economic mobilisation of the entire country – and thus affect the entire PLA – each TC is responsible for conducting operations in defined “strategic directions”89:

-

The Central TC (CTC) is tasked primarily with the defence of the capital, Beijing, and serves as a strategic reserve;

-

The Northern TC (NTC) covers conflict scenarios related to the Korean Peninsula;

-

The Eastern TC (ETC) focuses on maritime disputes with Japan in the East China Sea and operations aimed against Taiwan;

-

The Southern TC (STC) is responsible mainly for asserting control over the South China Sea but also for supporting the Eastern TC in a potential conflict involving Taiwan and the US; and

-

The Western TC (WTC) spans an enormous area in which operational planning is shaped not only by ethnic tensions in the Xinjiang Uygur and Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Regions but also by the border conflict with India.

The TCs oversee the regional headquarters of the service branches stationed within their respective areas of responsibility. To carry out their missions, they each command three group armies of the PLAGF – except for the STC and WTC, which command two. They also oversee between five and c. 15 units of the PLAAF as well as conventionally armed units of the PLARF. In addition, the NTC, ETC and STCs have command over the North Sea Fleet, the East Sea Fleet and the South Sea Fleet, respectively, of the PLAN. Of particular importance are the PLA’s expanded amphibious capabilities: the ETC now fields four amphibious combat brigades and the STC two, each of which is equipped with modern systems that are becoming increasingly sophisticated.90

The JOCs of each TC are central to command and control. They report to the JOCC of the CMC, which serves as a crucial interface between the TCs and the individual service branches. Effective coordination by the CMC JOCC is essential to the success of any operation. At the same time, efforts are being made to overcome coordination challenges through personnel structures and dual roles; if there is no officer from the navy or air force in command of a TC, one officer from each of these branches serves as deputy commander.91 In addition, the commanders of the TC headquarters of the army, navy and air force also serve as deputy TC commanders.

Moreover, one of the permanent deputy commanders of each TC headquarters holds the post of director of the Joint Staff Department, which is roughly the equivalent of NATO’s (J-3/5) operations and planning/ strategy staff sections. All officers serving in the JOCs are permanently stationed there, which allows them to fully identify with their roles rather than with the services to which they belong.92

The effectiveness of cooperation between the TCs and the individual service branches is all the more important because the TC headquarters of each service branch is also entrusted with four main operational tasks:93 1) serving as the hub for combat operations at the operational level, 2) forming part of the TC command post, 3) commanding routine administrative and leadership tasks and 4) functioning as headquarters for disaster relief and crisis response operations below the threshold of war.

To improve the units’ ability to conduct integrated joint operations in informationised conflicts, the hierarchies of the troop formations were flattened.

Brigadisation of combat troops

In April 2017, Xi announced that the PLAGF had been restructured into 13 newly-established or reorganised group armies (army corps).94 Wherever possible, these were formed exclusively of brigades, thereby completing the transformation, begun in the 2000s, of the Leninist structure of group army, division and regiment. The modern-day structure of the army combat troops is:

-

Group armies of 50,000–60,000 soldiers each

-

Brigades of 5,000–6,000 soldiers each

-

Battalions of 700–800 soldiers each.

A standard group army is composed of six combat brigades (“combined arms brigades”) and six specialised brigades from the following units: artillery, air defence, special operations, army aviation, engineers and chemical defence, as well as service support.95 As “new-type combat formations” capable of engaging in “informationised warfare”, these brigades and their battalions are organised to operate largely independently. In their standard configuration, combat brigades therefore include combined arms battalions comprising infantry, light and heavy armoured forces with corresponding firepower, as well as fire support and logistics units. Notably, there has been a significant increase in the number of special forces and army aviation units.

As “new-type combat units,” brigades and battalions are organised to operate largely independently.

Similarly, the PLAAF has been transformed from a territorial structure based on military districts into mission-oriented brigades. While its responsibilities and units in the areas of space and the information domain were transferred after 2015 to the Strategic Support Force and its successor organisations, it simultaneously incorporated numerous naval aviation units and naval air defence formations. With the exception of the airborne forces, which are organised into nine brigades and commanded as an airborne corps by the Air Force Command,96 all formations were subordinated to the respective TCs or TC headquarters of the air force. Within each TC, they are organised into brigades and grouped under two or three bases or air defence bases at the hierarchy level of deputy corps commander.97

The PLAN consists of three fleets that are subordinate to the NTC, the ETC and the STC. Its modernisation continues along three main developmental lines: evolving into a blue-water navy, becoming a joint operations force in the maritime domain and forming an interagency maritime force to assert China’s claims in the so-called “near seas” within the first island chain of the Western Pacific.98 Although the main focus is on a conflict with Taiwan,99 what stands out – alongside the development of three to six carrier strike groups – is the expansion of amphibious forces for operations in the South China Sea and beyond.100 With naval aviation reduced to carrier-based components and with operational responsibilities divided among the individual TCs, there is a particularly urgent need for coordination between the respective TC naval headquarters and the higher-level TC JOCs, the CMC JOCC and the national headquarters of the navy.101

The PLARF, which has been upgraded to the level of service branch in its own right, remains under the direct command of the CMC. It has been expanded to include nine bases at the level of army corps.102 Six bases operate missile systems – conventional and nuclear. One base manages the stored nuclear warheads, another has the resources for facility construction and yet another is responsible for system testing and training. Each base provides basic and further training to ensure the combat readiness of its troops and has the other necessary resources to carry out its operations.103 Between 2017 and 2019, the number of subordinate brigades grew rapidly from 29 to 39.104 Through the integrated command information system, these brigades are linked into processes at the level of TC.105

A systematic review of media reports and academic treatises on troop and staff training yields further indications of the status of, and progress towards, joint operations leadership.

Training for Joint Operations

The ability of commanders and their staffs to lead joint operations can be developed only through training and exercises that involve multiple service branches.106 From the very outset of the reforms, the PLA leadership understood that defining procedures along the new chains of command would require a lengthy process of adjustment and testing.107 The analysis carried out for this research paper of around 250 selected Chinese-language sources, on joint exercises conducted in recent years, led to the following findings. First, according to the directives of the CMC leadership under Xi, the training was designed to be realistic – exercises often took place with under conditions of high readiness, at night and in difficult weather and climatic circumstances and regularly involved confrontations with an active opposing force. Second, full-scale troop exercises have focused mainly on improving the coordination of operations within individual service branches.108 To be sure, many reports refer to scenarios in which coordination between ground units and supporting formations from the artillery and air force was trained as well. Yet, this aligns with the long-standing requirement (since the 1990s) for joint operations to be conducted under “modernised” conditions. Thus, the present research confirms earlier assessments that training activities remain too limited for the PLA to fully develop the capability to conduct joint operations.109 These are the conclusions that can be drawn, despite increased secrecy and censorship, which makes it impossible to carry out scientifically verifiable studies – especially of the increasingly frequent simulation exercises.

Pre-reform

Joint operations training was first introduced back in the period 2001–2005 as part of the five-year plan for the digitisation of headquarters. In 2005, two major exercises – named Lijian (Sharp Sword) – were held in what was then the military regions of Chengdu and Nanjing.110 The manoeuvres featured enhanced coordination between air and ground forces, including live-fire strikes.

Building on this, standardised training procedures were applied during the following two five-year plans (2006–2010 and 2011–2015). In 2009 alone, the PLA is reported to have conducted 18 large-scale exercises.111 These served to deepen civil-military integration, to rehearse the forward deployment of naval and air force units to operational areas and to simulate command processes at the operational level. In summer 2009, four divisions from the Shenyang, Lanzhou, Jinan and Guangzhou military regions were mobilised for the Kuayue (Stride or Crossing) exercise. This entailed moving large formations over long distances, which also posed logistical challenges. In addition, the Beidou satellite navigation system was deployed, along with capabilities for electronic and psychological warfare. According to media reports, the exercise, which was the largest “trans-regional” one until that point in time, involved around 50,000 troops and lasted a full two months.112

In the same year (2009), the Qianfeng (Vanguard) exercise – the first that could genuinely qualify as a joint exercise under the updated doctrine – took place.113 Like many subsequent iterations, it was held mainly at the Queshan training ground in the Jinan Military Region. In addition to a mechanised brigade and aviation regiment from the PLAGF, air force units from two military regions participated. A key innovation was the establishment of a joint headquarters.114 The military regional commands no longer presided over the exercises and for the first time, the commanding group army consisted solely of brigades and battalions.

The first Lianhe (Joint) exercise, which similarly took place in 2009, tested an integrated command platform intended to coordinate the deployment of formations from the army, the air force and the Second Artillery Corps (the predecessor of the PLARF). In 2010, the Shiming Xingdong (Mission Action) full-force exercise took place. It was led by a command staff set up specifically for that purpose and lasted 20 days. The participating units, which came from the Beijing, Chengdu and Lanzhou military regions, were redeployed across regional boundaries, along with navy and air force formations.

Other exercises were conducted in the period before the major reform. They point to extensive efforts to implement the target-centric warfare doctrine. The Qianfeng 2011 manoeuvres reportedly involved the use of a new command system that was able to process reconnaissance data, compile target lists and support decision-making.115 Further practical experience was gained at the Penglai 2012 and Lianhe 2012 exercises. The goal of Juesheng 2012a (Decisive Victory) was to use an integrated command system to plan and coordinate operations in line with the new doctrine. Finally, the Queshan 2012 exercise aimed to train commanders from 19 formations.116

The question is whether and how progress has been made towards capability development at the operational or campaign level – beyond manoeuvres involving two opposing brigades at training areas such as Queshan and Zhurihe – since the implementation of the reform from 2017 onwards.

Post-reform

During this period, the comprehensive restructuring of the PLA led to an interruption in the series of large-scale manoeuvres. According to Blasko, more than 1,000 units at and above the level of regiment were disbanded and more than 100 brigades and regiments relocated to new garrisons (along with the families of many PLA members).117 The same study also notes that 90 per cent of all officers from the former group armies and 40 per cent of those from former combat brigades were reassigned. Despite some reports suggesting otherwise, it is unlikely that large-scale training exercises resumed before the strict COVID-19 containment measures were lifted at the end of 2022.

In line with the directives issued by Chairman Xi, media outlets praised the suitability of the realistic training conditions “in all seasons, under all weather conditions and in all regions”.118 Furthermore, the use of drone swarms on land, at sea and in the air had reportedly been established and significant progress made in operational command across all five domains.

During the Cuihuo Luoyang 2018A exercise, the 83rd Group Army, together with elements of the Strategic Support Force, underwent training aimed at achieving informational superiority in the electromagnetic domain.119 The Lianqin Shiming 2018B exercise was somewhat larger in scale, mobilising not only elements of the Joint Logistics Support Force but also army and air force units from three provinces.120 Even more extensive and complex was Landun (Blue Shield) 18, which involved several brigades from the air force, army and rocket force. Supported by the Strategic Support Force, the exercise tested air defence operations using live fire and included long-distance troop movements and joint operations of various services and force types against an active opposing force.121 Finally, Yanbing 2021 focused primarily on training in logistics processes, with mechanised units being transported by rail and sea.122

The Kuayue (Crossing) exercise series at the Zhurihe training base in Inner Mongolia is noteworthy, too. In 2019, two brigades from the 82nd Group Army faced off against each other. Over the course of a month, the troops practised command capabilities, logistics and fire support for multi-domain defence.123 And another media report from 2021 highlights that approximately 200 commanders and staff officers from various group armies, with the participation of both ground and air force units had been trained as well.124 The Changkong Lijian (Sky Sword) air defence exercise, which took place the following year, similarly involved air force units working alongside ground forces. However, it lasted just two days.125

Compared with the exercises named above, those that took place after the visit to Taiwan in August 2022 by Nancy Pelosi, who at the time was the speaker of the US House of Representatives, are to be seen, above all, as efforts at intimidation, deterrence and the undermining of Taiwan’s autonomy. But at the same time, they provided valuable opportunities to rehearse larger-scale operations and elements of potential campaigns.

In early August 2022, the PLA held air and maritime exercises that took place over seven days under the leadership of the ETC and with the participation of the STC.126 More than 100 fighter jets and bombers were deployed, together with aerial reconnaissance and strike drones as well as 10 destroyers and frigates. Eleven ballistic missiles were launched into target zones around Taiwan. These activities were accompanied by actual cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns.127 At the same time, two aircraft-carrier strike groups conducted patrols in the waters surrounding the island. In April 2023, following the Taiwanese president’s trip across the US and high-level meetings there, the PLA held the five-day Lianhe Lijian 2023 (Joint Sword) exercise. The main component was the joint training of the army, navy, air force and rocket force aimed at establishing superiority in the maritime, air and information domains in order to sever Taiwan’s communication links with its partners and the wider international community, and to strike targets on the island. At times, more than 90 aircraft participated alongside 12 naval vessels, one carrier strike group and the China Coast Guard.

In May 2024, shortly after the inauguration speech of the new Taiwanese president, the Lianhe Lijian 2024A manoeuvres were held with the aim of “punishing separatist activities of the ‘Taiwan independence movement’”.128 As in 2022, the PLA defined training zones in waters around Taiwan and near the Taiwanese islands located close to the Chinese mainland. This time, however, both the navy and, in particular, the coast guard had a significantly stronger presence – the former with up to 27 vessels and the latter with 16. In October 2024, there was another military response after the Taiwanese president’s National Day speech. The short but extremely intensive Lianhe Lijian 2024B exercise lasted just one day but entailed the largest deployment to date. Once again, manoeuvres were conducted around Taiwan and on the offshore islands, with 17 coast guard ships patrolling inside seven designated zones and up to 135 aircraft and 17 warships from the navy, including a carrier strike group, also taking part. The main objective was a simulated blockade of Taiwanese ports.129 In early April 2025, the ETC led another exercise, which, like its predecessors, came after speech by the Taiwanese president. In the manoeuvres, later named Haixia Leiting 2025A (Strait Thunder), 13 warships accompanied by one carrier strike group and four coast guard vessels positioned themselves around Taiwan to simulate a blockade operation.130 Other service branches participated in the exercise, too, with the air force conducting missions that involved drones, helicopters and fighter aircraft. Commentary ostensibly from private citizens but approved by editors and the censorship authorities suggests that Taiwan should be deterred from taking steps towards formal independence through a demonstration of military readiness and the political will to use force.131

Assessment of exercises

China’s goal of flexibly deploying military formations across all hierarchical levels and coordinating with units from other branches across all five domains (land, air, sea, outer- and cyberspace) is ambitious. In this system, “the joint operations command system is an organic whole, with the strategic command organization [CMC] at its core, the joint campaign command organization [theatre commands] as its hub, and the joint task force and other command organizations as its foundation”.132 Yet, fundamental issues regarding command responsibility in the system appear to remain unresolved. Specifically, experts from the NDU have emphasised that “the establishment and operation of a joint command system must follow the principles of simplicity, practicality and effectiveness. Therefore, the vertical and horizontal relationships between the various organisational units at all levels of the system require further clarification […] and responsibilities must be flexibly defined and assumed according to the combat requirements.”133

Fundamental issues about command responsibility in the new system appear to remain unsolved.

Against this backdrop, it should be understood that the frequent calls for improving the training of “talented” cadres and optimising technical systems are symptomatic of difficulties in the organisational culture of the PLA, if not signs of the impossibility of conducting comprehensive, effective and precise warfare. In particular, the repeated use in this context of adjectives such as “scientific” (kexue) and “rational” (youli) as well as the weighty phrase “seeking truth from facts” (shishi qiushi) has a critical undertone – one that points to a lack of discipline, passivity, excessive bureaucracy and approaches to problem-solving that are ideologically driven and impractical.134

The numerous reports about highly motivated, eager-to-learn and “innovative” non-commissioned officers,135 junior officers and staff officers136 should be considered in this light as well. These individuals ostensibly show leadership, realise their own potential and help their respective organisational units – and thus the PLA and even China as a whole – make advances. However, it is not they but only a handful of figures at the highest leadership level who have the power to improve the institutional framework and organisational culture of the PLA.

In the one-party state, the main instrument for such improvement is the all-encompassing organisation of the political work departments, Party committees and Party cells at all levels. Under the leadership of a member of the CMC, this organisation is responsible for personnel administration, which includes conducting performance evaluations, deciding on promotions, organising ideological training, maintaining party discipline and providing for the welfare of the troops. Its branches are also consistently tasked with the command of military formations. Even in combat, operational decisions are made collectively.137 How this system of political ideological control can be reconciled with the need for rapid decision-making and complex coordination in informationised warfare remains unclear, however. The Party committees, which have been strengthened again under Xi, appear to be hindering efforts to reduce the bureaucracy within military structures.138 Moreover, it is likely that there is enormous pressure exerted by the requirement to discipline cadres through ideological indoctrination and exact constant displays of loyalty from them through ritualistic behaviour. As a result, responsibilities and de facto decision-making authority are delegated upwards, while subordinates are strictly disciplined. This organisational culture directly contradicts the mission command model as prescribed by PLA doctrine. In such a system, the repeated calls for “iron discipline”, an “iron will” and “the promotion of a fighting spirit” are bound to be neither effective nor promising – especially given that in 2024 even General Miao Hua, the top political commissar and guardian of the PLA’s loyalty to the CPC, was removed from his post over disciplinary violations.139 Such incidents reveal the limits of an army of the Party.

Conclusions

The very nature of modern warfare is shrinking geographical distances, which, in turn, necessitates a faster pace of military operations. This significantly increases the demands made of military organisations. It is likely that the PLA will meet the technical preconditions for effective warfare along China’s periphery by the middle of this century, if not earlier.140 However, its ability to conduct high-intensity operations beyond the first island chain in the Western Pacific will remain limited. That is because it does not yet have a crisis-resilient military infrastructure based on a network of reliable allies.

Besides technical obstacles, the PLA faces institutional challenges over coordinating joint military operations across all service branches and domains simultaneously. These challenges stem from the need to clearly define responsibilities and efficiently allocate resources – both between and within the individual service branches and TCs. The PLA has yet to resolve such issues.141 In order to address these shortcomings and the currently limited number of large-scale live exercises at the levels of TC and army corps, it is possible that the PLA will increase the frequency, scale and complexity of manoeuvres around Taiwan.