When Home Becomes Uninhabitable

Planned Relocations as a Global Challenge in the Era of Climate Change

SWP Research Paper 2026/RP 01, 22.01.2026, 34 Seitendoi:10.18449/2026RP01

ForschungsgebieteNadine Knapp is an Associate in the Global Issues Research Division at SWP.

This paper was written as part of the research project “Strategic Refugee and Migration Policy”, funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

The author would like to thank Emma Landmesser for her excellent support in researching and creating the timeline, and Meike Schulze for her constructive expert review. Further thanks go to the SWP editorial team.

-

With climate change advancing, the planned relocation of entire communities from risk areas is becoming unavoidable. It is already a reality worldwide and will become increasingly necessary in the future as a measure of climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

-

Relocation can save lives and reduce the risk of displacement. Nevertheless, this measure is considered a “last resort” because it is expensive, deeply affects livelihoods, social networks and cultural identities, and carries new risks.

-

To be effective, it must be participatory, human rights-based, and accompanied by development-oriented measures that strengthen the well-being and resilience of those affected and reduce structural inequalities.

-

Many places lack the political will, concrete strategies and resources for this – especially in low-income countries with already limited adaptation capacities. These countries are therefore heavily dependent on international support, which has mostly been fragmented, ad hoc and uncoordinated.

-

The longer the absence of adequate structures persists, the greater the risk that human security will be severely compromised, fundamental human rights violated and entire communities (once again) displaced – posing risks to regional stability and global security.

-

The German government should specifically address gaps in the international system, facilitate access to knowledge and resources, and strengthen multi-sectoral learning. Germany’s current engagement in Fiji should be expanded in the medium term to other climate-vulnerable regions and countries, with a focus on community-driven relocation projects.

Table of contents

2 What Are Planned Relocations – and Why Are They Necessary?

2.1 Growing salience and need for support

2.2 Terminological and conceptual classification

2.2.3 Forms of planned relocation

3 Practical Insights: Challenges and Lessons Learnt

3.1 Developing national strategies and regulatory approaches

3.2 High costs and resource intensive

3.3 Political interests and potential for abuse

3.5 Diverging assessments of risk and uninhabitability

3.7 Learning from development-induced resettlement contexts

4 Status Quo of International Engagement

4.1 Relevant institutional processes, frameworks and guidelines

4.2 Fragmented landscape of actors

4.3 International financing instruments

5 Sustainable International Engagement

5.1 Preconditions for effective international support

5.1.1 Multidimensional approach

5.1.2 Consent as a prerequisite

5.1.3 Relocation as a “last resort”

5.2 Starting points for the German Federal Government

5.2.1 Action field 1: Supporting cross-sectoral cooperation

5.2.2 Action field 2: Improving international coordination and cooperation

5.2.3 Action field 3: Promoting knowledge-sharing and joint learning

5.2.4 Action field 4: Strengthening political frameworks and promoting implementation

5.2.5 Action field 5: Targeted provision and mobilisation of financial resources

Issues and Recommendations

Millions of people around the world are already suffering from the consequences of climate change. Exceeding the 1.5°C limit set in the Paris Agreement will intensify extreme weather events such as heavy rainfall and droughts, accelerate slow-onset environmental changes, destroy livelihoods and make some places, especially coastal villages, increasingly uninhabitable. As a result, planned relocations – in which entire communities are permanently relocated from risk areas to safer places – are likely to happen more in the future. However, implementing such relocations is time-consuming and costly, and it places significant burdens on the people affected. Such relocations also face considerable resistance, as many people do not want to leave their homes, despite increasing climate risks. Relocation is therefore politically controversial and is viewed as a “last resort” when all other adaptation options have been exhausted.

Despite these risks, relocation has long been a reality worldwide: Between 1970 and 2020, more than 400 documented cases were identified across 78 countries, including Fiji, Panama and the United States. In Germany, too, following the flood disaster in the Ahr Valley, there was public discussion about not resettling flood victims in endangered areas and instead relocating them to safer sites. The issue thus affects people worldwide and raises similar questions regardless of geography about home, attachment to place and cultural identity.

At the same time, planned relocations are gaining importance at the international level: Climate and migration policy frameworks increasingly recognise them as a tool for disaster risk reduction, climate adaptation and as a response to loss and damage. As early as 2010, the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed in Cancún to take measures to enhance understanding, coordination and cooperation with regard to planned relocation.

However, only a few countries have made sufficient preparations. Hardly any country has comprehensive national frameworks for planned relocation; many lack the political will, resources, capacities and knowledge to design relocation in such a way that the rights of those affected are protected and additional damage is avoided. For low-income countries in particular, planned relocation is almost impossible to manage without substantial investment and international assistance.

Although a growing number of United Nations (UN) institutions, development banks, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and donor countries are now involved in the issue of relocation, none of these actors has a clear mandate, leading to fragmented international action, the inefficient use of limited resources and competition between international actors. Given the growing need for relocation support, the existing system is not sustainable. The situation is exacerbated by the significant funding cuts that have been made in development cooperation and humanitarian aid – for example by the United States and major European donor countries such as Germany – which are jeopardising the existence and effectiveness of important actors in this field.

Scientific findings and experiences worldwide show that relocation only creates sustainable prospects if it goes beyond mere risk reduction and is participatory, human rights-based and accompanied by development-oriented measures that strengthen the well-being and resilience of those affected, in addition to reducing structural inequalities in their new place of residence. Otherwise, there is a risk that the people who have to relocate will not be able to establish themselves in the destination region and will be displaced (again) in the long term.

The study examines how affected communities and governments in the so-called Global South can be effectively supported in planned relocations and what role international actors and donor countries – especially Germany – should play in this process. It consolidates the existing knowledge on planned relocations, highlights the associated challenges and takes stock of international support structures. The study thus provides a comprehensive overview that has been lacking in German-speaking countries to date.

Current geopolitical shifts and drastic funding cuts require a strategic reorientation of Germany’s foreign, climate and development policy. Germany could distinguish itself as a reliable and capable cooperation partner in tackling the climate crisis, particularly when it comes to planned relocation. It is one of the few donor countries already involved in this area. The commitment of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) in the Fiji Islands has contributed significantly to the development of context-specific relocation guidelines and standard operating procedures that are now considered best practice worldwide. This example shows how such processes can be constructively supported.

Without adequate support for low-income countries from wealthy industrialised countries such as Germany, there is a risk of even greater humanitarian costs, growing displacement risks and setbacks in poverty reduction. Climate impacts can also destabilise entire regions, increase the likelihood of conflict by serving as risk multipliers and disrupt global supply chains. International engagement is therefore not only a question of global climate justice, but also a matter of international and national security. Such an approach is also in line with the German government’s goal of integrating foreign, security, and development policy.

Despite its own austerity measures, Germany should therefore honour its commitments to international climate finance and promote adaptation measures in an even more targeted manner to prevent climate change-induced displacement. The aim of Germany’s development cooperation and humanitarian aid must be to enable vulnerable communities and governments to respond to climate risks, weigh up adaptation options and, if necessary, begin to prepare for planned relocations well in advance.

Bilaterally, Germany should push ahead with the implementation of the governance framework developed with the Government of Fiji and, in the medium term, extend its engagement to other climate-vulnerable partner countries. In addition, the Federal Government should specifically address gaps in the international support system, advocate for uncomplicated access to resources and knowledge, and promote cross-sectoral learning. In this way, Germany would not only be able to promote participatory relocation processes that are human rights-based and strengthen the leadership of affected communities; such an approach would also increase its influence in international climate, development and migration policy.

What Are Planned Relocations – and Why Are They Necessary?

Climate change is already causing enormous costs and damage, for example through rising sea levels and an increase in extreme weather events. In 2024 alone, around 45.5 million people worldwide were displaced within their own countries due to weather-related disasters such as storms and floods – this sets a new record and is significantly more than the 20.1 million who had to leave their homes in 2024 as a result of conflict and violence.1 Although not every natural disaster can be directly attributed to climate change, it increases the overall frequency and intensity of such events and accelerates environmental changes that are rendering entire areas uninhabitable.2 Climate change is therefore already one of the most important drivers of forced displacement and migration, alongside conflicts and violence, fragility and economic inequality.3

Growing salience and need for support

In addition to the primary goal of mitigating the worst effects of climate change, countries and regional and international actors worldwide are more and more focusing on targeted adaptation measures. These are intended to make particularly vulnerable population groups more resilient to climate risks and to limit losses and damage. Measures are being implemented in the areas of civil protection and disaster assistance, disaster risk reduction, humanitarian aid and development cooperation.4 These approaches primarily aim to enable those living in vulnerable communities to remain in their places of origin. Nevertheless, with the increasingly negative effects of climate change, another adaptation strategy is coming into focus: strengthening mobility options such as regional freedom of movement and regulated labour migration.

In addition, local and national governments are also considering relocating entire communities out of high-risk areas, either in response to or in anticipation of disasters and environmental changes. In some cases, the affected communities – most of which have their own administrative and organisational structures – decide for themselves whether to leave endangered locations in order to settle in new, safer places. A global mapping5 published in 2021 of such planned relocations identified more than 400 cases involving 78 countries between 1970 and 2020; however, the actual number is likely to be significantly higher.6 Numerous other relocation projects are already in the planning stages. Relocations are now taking place in all regions of the world. Around 40 per cent of all cases were in Asia, closely followed by the Americas. About 10 per cent of identified relocations were in Africa, 9 per cent in the Pacific, and only a few in Europe and the Middle East. In terms of total population, however, the Pacific region is the most affected. Although the media repeatedly predicts that entire island states will become uninhabitable due to climate change, and their inhabitants will have to relocate to neighbouring countries, there have been few cross-border relocations up to now. However, they may become inevitable in the future for Small Island States such as Kiribati.7 Planned relocations therefore usually take place within national borders.8

Not only developing countries and emerging markets are threatened by the danger of certain areas becoming uninhabitable, but also wealthy industrialised nations.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the need for planned relocations is expected to continue rising, primarily to support those who are unable to move voluntarily.9 Households and communities in coastal and mountainous regions – where even minor environmental changes have serious impacts on living conditions – are particularly affected. The threat of certain areas becoming uninhabitable affects not only developing countries and emerging markets, but also high-income countries such as the United States – particularly parts of Alaska, where some relocations are already being implemented. In European countries, too, for example on the north coast of Portugal (e.g. in Pedrinhas and Cedovém), planned relocations in highly endangered areas are being discussed.10

However, implementing planned relocations poses a significant challenge, especially for low-income countries, which are severely affected by the consequences of climate change, as they are very exposed to climate risks and have limited resources for adaptation. High levels of debt are placing additional strain on the tight public budgets in many countries of the so-called Global South.11 Around 70 per cent of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, are so heavily indebted that they cannot afford the necessary investments for climate adaptation measures nor for implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals or the African Union’s Agenda 2063.12 At the same time, low-income countries account for only a marginal share of global emissions. Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, is responsible for only 5 per cent of these emissions.13 Not least in the interests of climate justice, it is therefore necessary and imperative that wealthy industrialised countries provide financial and technical support to promote sustainable solutions that help people to remain in their places of residence or enable them to access safe mobility options.

Terminological and conceptual classification

Compared to other mobility patterns in the context of climate change, planned relocations have long been under-researched. Instead, the relevant literature has focused on disaster-induced displacement.14 Since the 2010s, however, research on climate-related relocations has been developing dynamically. Initially, it was case studies of well-documented relocations that were predominant. There are now more comparative analyses.15 In particular, the aforementioned global mapping from 2021 and the (regional) studies16 based on it have significantly expanded the evidence base. This has contributed to a better understanding of the phenomenon and its specific characteristics and has provided important insights for shaping policy and practice.

Definition

Relocations can take place for a variety of reasons, for example in the course of development projects, such as the European Union’s (EU) Global Gateway Initiative, or in connection with mining and raw material extraction. In addition, people have long been resettled in the context of armed conflicts in order to monitor and/or protect them. Governments also order resettlements for (geo)political reasons, for example to secure border areas or control strategic resources.17

The concept of “relocation” is therefore by no means new. Nevertheless, the term is neither used consistently nor defined in a legally binding manner. Instead, various terms are in circulation, especially in English-speaking countries, such as “(planned) relocation”, “(involuntary) resettlement” and “managed retreat”. These terms differ not only linguistically; depending on the context, they also have their own meanings in terms of the practical arrangements for the respective relocation and the associated legal entitlements and responsibilities. Definitional clarity is therefore essential when international actors decide to support relocation.18

A common term that has become established in connection with climate change-related relocation is “planned relocation”. It is used by the signatory states to the UNFCCC and also by some affected states, such as Fiji, in national relocation projects.19 In the absence of a binding multilateral definition of “relocation”, this study uses the widely accepted definition, which appears in the scholarly literature and (climate) policy contexts and underpins the Nansen Initiative’s Protection Agenda,20 a document endorsed by 109 states in 2015. The explanation of the term contained therein largely coincides with its use in politics and academia.21

Accordingly, “planned relocation” is understood to mean a controlled process in which people are resettled from areas at risk to safer sites. The term also encompasses the (re)building of infrastructure, public services, housing and livelihoods for those affected at the destination. As a rule, this can involve the relocation of household groups or an entire community under the authority of the state with external support. There is also broad agreement among the research community and practitioners that planned relocations are complex instruments fraught with numerous risks and should only be considered as a “last resort” when other risk reduction measures and adaptation options have been exhausted or are not feasible.22 Planned relocations thus have a number of specific characteristics that fundamentally distinguish them from other forms of climate change-induced mobility such as migration, displacement and emergency measures such as evacuations.23

Drivers and motivations

Planned relocations can be both a form of disaster preparedness and of adaptation to climate change. In addition, a conceptual distinction is often made between reactive and preventive relocation: Reactive relocation takes place after a disaster, when the place of origin is no longer considered habitable. The aim is to create a permanent solution for people who have been displaced, for example, and can no longer return safely to their homes. Preventive relocation, on the other hand, aims to relocate people in a timely manner from areas with a high or increasing risk of natural disasters and climate change before acute danger arises or their homes become uninhabitable. In practice, relocations have often taken place after sudden disasters or when they are imminent. However, as the modelling of future scenarios improves, preventive, longer-term relocations are becoming more important.24 Nevertheless, relocations are usually the result of a combination of both approaches, that is, a response to realised harms and, at the same time, a precautionary measure in view of impending climate risks.25

|

Info box 1 Planned Process: It is a “planned process” that usually takes place with the support of external actors under the authority of the state. Initiators and supporters can belong to the community itself as well as to governmental, civil society or international institutions. Permanent Intention: A key feature is the “intended permanence” of the measure, which distinguishes it from temporary forms of movement such as evacuations and accommodation in emergency shelters. Collective Movement: This usually involves relocation at the community or household group level, as opposed to individual, spontaneous migration or a state-sponsored move. A group of persons is relocated, usually with an administrative or organisational structure that is to be re-established in the new location. As a “Last Resort”: Planned relocation is generally considered a measure of “last resort” and should only be carried out if other less disruptive adaptation measures, such as the construction of dykes, are insufficient to enable people to remain in their homes. Securing/Rebuilding Livelihoods: The aim is not only to secure livelihoods and rebuild the physical infrastructure of the affected community, but also to preserve community dynamics and restore social and cultural practices. |

The decision to carry out a planned relocation is usually triggered not by a single event, but by the interaction of several recurring and overlapping hazards (multi-hazard contexts). It is often a combination of slow-onset stress factors (e.g. sea level rise) and sudden-onset stress factors (e.g. floods) that severely limits the options available to those affected.26 In addition to exposure to climate risks, a variety of social, cultural, political, economic and other non-climate-related factors influence the decision for or against relocation – both on the part of the people affected and on the part of government or external actors.27

Although displacement tends to be at one end of the spectrum of coercion and voluntariness28 and migration at the other, planned relocations can be considered voluntary or involuntary. Classification is often difficult, as even seemingly consensual relocations can have a “forced” character, for example when state actors urge residents in a risk area to relocate. A key criterion can therefore be the extent to which those affected are guaranteed opportunities for choice, consultation and participation.29 It is also helpful to distinguish between relocations that are led by the affected community (community-led relocations) and those that are not.

Forms of planned relocation

Relocations can be initiated by individuals, communities or government actors – but also by NGOs or other external actors. The global mapping of planned relocations mentioned above shows that the scale varies greatly: It ranges from very small measures involving only four households – as in the village of Vunisavisavi in Fiji – to larger relocation projects involving around 1,000 households, as in the case of Gramalote in Colombia. Some relocations take place between only one place of origin and one destination site, which is often a short distance from the original location so that those affected can continue earning their livelihoods (e.g. agriculture, fishing). Other relocations involve multiple origins and destinations, which carries the risk of fragmenting community structures – especially when population groups are merged or distributed across different locations.30

Due to this diversity, there is no universally applicable political, strategic or operational approach to relocation.31 Rather, its design and implementation vary depending on climatic, geographical, political and socio-economic conditions. Differences exist, for example, in the degree of planning, participation mechanisms, the extent of state intervention, the legal and political frameworks, financing and access to public services.32

Practical Insights: Challenges and Lessons Learnt

Planned relocations are complex, resource-intensive and politically challenging. The experience to date has been largely negative, both for the communities directly affected and for the host communities. Relocations are often associated with serious violations of fundamental human rights – for example, in relation to the supply of water and food, housing and sanitation, education opportunities and even health and life itself.33 After relocation, those affected often lose their livelihoods, cultural ties and social networks, while at their new location they face inadequate infrastructure, limited access to public services and a lack of opportunities to secure their livelihoods.34 In only about half of the globally documented relocation cases, for example, were those affected able to maintain their previous standards of living.35 Relocation often shifts risks rather than reducing them in the long term, for example when the new location is exposed to other climate or environmental hazards. This can then lead to people returning or facing (renewed) displacement.36

Relocation can be a maladaptation to climate change if it creates new threats, vulnerabilities or inequalities.

Relocation can therefore be a maladaptation to climate change, especially if it gives rise to additional risks, vulnerabilities or inequalities.37 In the past, relocation processes have cemented existing power relations and exacerbated social disparities, not only in socio-economic terms, but also in terms of gender, age, marital status and ethnicity.38 Women, for example, are often tenants or land users. They rarely own land themselves, which is why relocation programmes that require land ownership and property rights often neglect their needs and customary rights.39 Indigenous groups, whose livelihoods, culture and identity are often closely linked to their land, are also particularly affected. For many of them, the loss of their land is therefore far more than just a physical change of location – it poses a threat to their entire way of life.40

However, scientific case studies and comparative analyses also show that losses and damages can be significantly reduced if governments plan ahead, provide sufficient resources, create transparent and binding framework conditions, and put protective measures in place to safeguard the rights of those affected. In addition, better relocation outcomes can usually be achieved if the affected communities are involved in decision-making processes and can maintain their livelihoods as well as cultural and family ties in their new location.41

Nevertheless, relocation is associated with tensions that cannot always be resolved and are usually accompanied by political controversy, particularly with regard to the question of its necessity: Who decides whether it is still reasonable to remain? What happens if some community members choose to stay behind? Can governments order relocation to protect human lives, even against the will of individuals? And how can we prevent the instrument of relocation from being misused for economic or political motives?42 The following sections summarise key areas of tension as well as the challenges associated with planned relocations, while also presenting effective practices and success factors that can lead to better outcomes.

Developing national strategies and regulatory approaches

Under international law, states bear the primary responsibility for protecting people within their territory, including in the event of disasters and environmental hazards. They are obliged to take preventive measures to protect life, physical integrity and health – which may also mean removing people from a danger zone or, in exceptional cases, carrying out relocation. Planned relocations within national borders are therefore primarily the responsibility of nation states, and their implementation is determined by their legal systems.43

At present, the legal framework for planned relocations varies greatly from country to country. Only a few countries – including Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Solomon Islands and Uruguay – had developed relocation-specific national strategies and/or laws by the end of 2024. Nevertheless, even many of these regulations lack important elements such as clear financing arrangements and guidelines that ensure adequate protection or systematic involvement of affected communities.44 Relevant provisions are often also enshrined in other policy areas. For example, countries45 such as Vanuatu46 and Bangladesh47 have developed national frameworks that focus primarily on climate change or disaster- and climate change-induced internal displacement, but they also recognise planned relocations as a possible measure for climate adaptation, disaster preparedness or as a durable solution. In some cases, states have also committed themselves in such documents to developing specific relocation guidelines that are intended to establish an overarching framework, clear responsibilities and protection standards for planned relocations.

Fiji and the Solomon Islands are the only countries to have developed such guidelines to date. Fiji is considered a pioneer in this field, as it has one of the world’s most comprehensive frameworks for planned relocation (see Info box 2).

The island nation of Solomon Islands also has some of the most progressive regulations for planned relocation in the world: The guidelines are based on a people-centred, participatory approach; emphasise the protection of standards of living, rights and cultural identities of those affected; and provide for complaint mechanisms during the relocation process.48 However, they do not contain any details on the financing of relocation. The concrete implementation of the guidelines is still pending. Weak institutions and disputed land claims further complicate implementation: 87 per cent of the country is subject to customary law, with land and resource use rights largely unregistered and often disputed.49

|

Info box 2 |

||

|

Like many island nations, Fiji faces weather-related hazards that are exacerbated by climate change. In 2014, based on the projected impacts of climate change, the government identified 676 coastal communities that would need to relocate in the coming decades. Of these, 42 were prioritised for relocation as soon as possible. Against this backdrop, National Planned Relocation Guidelines (2018) and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) (2023) were developed. The latter were drawn up in a detailed consultation process with various stakeholders, including government agencies, NGOs, civil society organisations, academic institutions, private actors, regional organisations and international development partners. In 2019, Fiji became the first country in the world to set up a national Climate Relocation of Communities (CROC) Trust Fund with earmarked funds for planned relocation. In addition to bilateral and international contributions, 3 per cent of the revenue from the country’s environmental and climate adaptation levy (a tax on luxury services and utilities) flows into the fund. In addition, the affected communities are expected to contribute their own resources and labour. In 2021, the legal framework was enshrined in law in the Climate Change Act. In addition, representatives of relevant ministries coordinate the implementation of all related initiatives and processes in a specially |

created Taskforce on the Relocation and Displacement of Communities Vulnerable to the impacts of Climate Change.a Fiji thus has one of the world’s most comprehensive policy approaches to planned relocation. This includes precise guidelines for protecting and safeguarding the well-being of the affected population groups and for involving various interest groups – including women, older people and people with disabilities – throughout the relocation process. In addition, the island nation has established clear responsibilities and participation mechanisms for the planning, financing and implementation of relocations. The regulations are supplemented by instruments for monitoring, evaluation and capacity development. However, the size of the Fijian trust fund is very small; only New Zealand has pledged funds (NZ$5.6 million), and the first relocation financed by the fund has been significantly delayed.b a See Government of Fiji, Climate Relocation of Communities Trust Fund. Understanding the Climate Relocation of Communities Trust Fund and How You Can Contribute, Information Brief 2 (May 2023). b Merewalesi Yee et al., “‘Where My Heart Belongs’: Disaster-induced Displacement in Nabavatu Village, Fiji”, Researching Internal Displacement (blog) (March 2025), 4f. |

|

High costs and resource intensive

Planned relocations are extremely costly and difficult to finance. The financial costs vary considerably – from more than US$100,000 per person for relocation projects in coastal regions of Louisiana and villages in Alaska to less than US$10,000 per person for relocations on Fiji.52 Although some countries – especially in the so-called Global North – can draw on their own resources, in other regions of the world external support from international financial institutions or other donors is often indispensable. For low-income countries in particular, which usually lack financial resources and access to international credit and capital markets, such projects are hardly feasible without third-party assistance (see section “International financing instruments”, p. 24).53

The approaches and instruments used to finance planned relocations vary greatly. The same applies to the distribution of costs and responsibilities. However, ad hoc funds are often combined from various funding sources – such as (sub-)national and local governments, (international) NGOs, churches, philanthropic foundations, donor countries, multilateral development banks (MDBs), international organisations or the private sector. In some cases, the affected communities themselves bear the costs, for example through crowdfunding, as in Pune (India) and Panama. The funding mechanisms used to cover the necessary expenses range from government funds, specific public taxes, insurance, loans, bonds, donations, emergency funds and grants to trust funds such as the CROC Trust Fund in Fiji (see Info box 2, p. 14). As a rule, however, countries do not have clearly defined financing instruments for planned relocations. The lack of transparent, publicly available information on the funding sources and mechanisms actually used makes it difficult to comprehensively analyse existing financing practices for planned relocations.54

The complexity, long-term planning requirements and costs of relocation processes often overwhelm the resources and administrative capacities of the countries concerned.55 In some cases, a lack of government action and funding have also led to urgently needed relocations being postponed indefinitely or only partially implemented, with significant socio-economic consequences for the people affected.56

Political interests and potential for abuse

The implementation of planned relocations depends not only on legal frameworks and financial resources, but also significantly on the political will of the national government and the responsible authorities.57 Relocation decisions are often controlled by the state and not infrequently motivated by political and/or economic considerations – often without sufficient consultation or involvement of the affected population (see section “Degree of participation”, p. 17).58 Political motives and cost-benefit considerations influence who is resettled and where as well as when and how people are moved to new locations. Changes in governments and priorities can delay the implementation of planned relocations by decades.59 This complicates planning, increases the risk of new vulnerabilities and undermines the trust of those affected.60

Furthermore, there is a risk that climate adaptation will be used as a pretext to push through specific interests or legitimise unpopular or previously discredited relocation measures. This is particularly problematic when climate change-induced relocation is used as a tool against politically marginalised communities.61 For example, the government’s relocation efforts in the Lempira region (Honduras) after Hurricane Mitch must be seen in the context of political interests aimed at displacing the population from Celaque National Park.62

Some affected communities therefore view state-initiated relocations with great scepticism – not least because these often evoke memories of events from the colonial era as well as of past forced relocations and expulsions, which have often had lasting negative impacts on the degrees of trust in state measures.63 One example of this is the Indigenous communities in Alaska, whose experiences with previous state-ordered forced relocations continue to have an impact today and are reflected in the deep mistrust of government authorities.64

At the national level, there is also often a lack of transparency about how and why governments initiate, support or delay relocations, and which factors or stakeholders influence these decisions. At the same time, there is rarely any accountability for those who plan and implement relocations. In addition, there is often a lack of political incentives to systematically involve affected communities in decision-making processes and to adequately take their needs into account.65

National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), which are an internationally recognised planning tool under the UNFCCC, could create greater transparency. However, of the 53 NAPs submitted to the UNFCCC by March 2024, only 26 mentioned planned relocations – mostly in passing and without specifying the scope, timeframe or areas affected. Only 45 per cent of the 53 contained any concrete details.66 At the same time, there is a gap in the documentation: A comparison of the submitted national reports on adaptation measures67 with the aforementioned global mapping of more than 400 documented relocation cases in 78 countries shows that many of these countries either did not submit reports or did not mention relocations in them – even though such measures have long been taking place on the ground.68

Complex land issues

Further challenges in permanent relocation from hazard-prone areas arise from unresolved issues regarding land (use) rights. This problem affects both the people being resettled and those whose land is to be used as the new location.69 For example, authorities can restrict the use of certain spaces (e.g. as a place of residence) or revoke land ownership rights if a location has been identified as a risk area. Legal safeguards to effectively recognise, secure or compensate existing land rights – especially customary and traditional rights – are often lacking. In addition, people who have to make their land available for relocation often do not receive adequate compensation. This can lead to significant conflicts. One example of this is from Mozambique: After Cyclone Idai struck in 2019, there were 80,000 people resettled to 66 new locations. Gaps and inconsistencies in the legal framework – combined with selective application of the law – meant that the land rights of both the relocated people and the host communities remained unprotected. The unclear legal situation around land ownership and expropriation not only posed a key challenge for the relocation programme, but also led to tensions between the resettled households and the host communities.70

Diverging assessments of risk and uninhabitability

Decisions about planned relocations often revolve around the question of when a place is considered uninhabitable – and at what point it is no longer reasonable or safe for the population to remain there.71 However, defining such thresholds is particularly challenging. There is currently no internationally recognised definition of “habitability” or “uninhabitability”, and it is often difficult to determine a clear “risk threshold” at which relocation becomes necessary, as the contexts regarding hazards and disasters vary significantly. In addition, the risk tolerance of those affected is individual and situation-dependent: It depends not only on the actual threat situation, but also on social ties, power dynamics, cultural and emotional attachments to the place, and whether alternative means of securing a livelihood are available. Ideas of habitability cannot be reduced to purely material aspects of human security, such as the availability of housing, food or water. They are deeply linked to culturally and historically anchored worldviews and outlooks on life and are embedded in local knowledge systems.72 “Uninhabitability” and “habitability” form a dynamic continuum shaped by a wide range of factors. It is precisely this multidimensionality that makes it challenging to clearly attribute the causes of uninhabitability to climate change and to derive political responsibilities from this. At the same time, in many cases, a clear attribution of causes – especially to climate change – is central to accessing financial support, for example through international climate funds (see section “International financing instruments”, p. 24).73

Although scientific progress has recently been made in conceptualising uninhabitability, government-led relocation decisions are often based primarily on biophysical risk assessments – and they depict “uninhabitability” as an objective, irrefutable finding. The authorities’ assessments often contrast sharply with the affected population’s knowledge of their environment, their perception of risk and their risk tolerance.74 One illustrative example is from the Chilean community of Villa Santa Lucía, whose residents rejected government relocation plans after a mudslide caused widespread destruction in December 2017. Their refusal was based on a different risk assessment, which in turn was influenced by specific local beliefs about nature and human–nature relationships.75

Managing this tension requires a high degree of sensitivity – and, in particular, a willingness to incorporate different risk assessments into the handling of potential hazards.76 One example showing such an integrative approach is from Fiji (see Info box 2, p. 14). That is where a comprehensive matrix for Climate Risk and Vulnerability Assessment77 was developed within the framework of the SOPs and with the support of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) as the implementing organisation and the state-led Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) initiative. In addition to biophysical and climatic data, this matrix also takes into account socio-economic and cultural aspects at the community level. It is particularly noteworthy that both economic and non-economic losses and damage are taken into account, such as the loss of traditional social structures.78

Degree of participation

The extent to which local communities are involved in decisions about relocation varies greatly. One example of a community-led initiative can be found in Alaska. There, on the west coast, the Newtok Traditional Council has developed a detailed relocation plan with short- and long-term goals and projects. The approximately 360 residents of the community were actively involved in the process and able to vote on relocation options in several rounds.79 In contrast, when relocation is initiated and driven by external actors such as governments or NGOs, measures are often planned and implemented without sufficiently consulting people affected and host communities. There is often a lack of information, transparency, coordination and inclusive formats, which would enable broad participation.80

Studies show that the outcomes of relocation processes are significantly better when the affected communities are able to participate fully.

The degree of participation not only influences whether relocation can be considered voluntary or forced (see section “Drivers and motivations”, p. 10). Numerous studies also show that the outcomes are greatly improved when affected communities are actively involved in the decision-making processes and are able to collaborate fully. If the local perspectives and ways of life of the affected population groups are ignored, however, problems may arise with regard to relocation decisions and procedures, potentially exacerbating the marginalisation and erosion of the cultural and social capital of the communities. It can also lead to rejection and resistance to the project.81 Examples such as the failed project to resettle the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe from Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana illustrate that the perspectives and capacities of the host communities also need to be taken into account to a greater extent. New arrivals and relocations often place a strain on the infrastructure, labour market and social fabric of the host communities. A lack of acceptance or the emergence of conflicts can decisively reduce the success of the relocation.82

At the same time, however, a holistic, participatory process requires a considerable investment of time and resources. Communities are also heterogeneous; the positions they express during consultations can be challenging to integrate, as they may contradict each other.83 In situations of acute disaster, this makes it difficult to take the necessary decisions quickly. To counteract this dilemma, participatory processes should ideally be preventive-oriented and take place in advance of disasters.84 Another challenge is that communities may not want to relocate as a whole, or parts of them may decide to stay behind (“voluntary immobility”). At the same time, governments have a duty to protect their populations and act in the event of life-threatening danger – if necessary and under certain conditions, even if this means acting against the will of individuals or entire communities.85

Learning from development-induced resettlement contexts

Planned relocations in the context of climate change and disasters show numerous parallels to resettlements and displacements in the context of large-scale development projects, such as the construction of dams (scientific term: “development-induced displacement and resettlement”, DIDR). The similarities relate in particular to the planning and implementation processes as well as the associated risks86 for those affected and the host communities – such as landlessness and unemployment, food insecurity, loss of property and resources, social exclusion and psychosocial stress.87

The idea for a policy that minimises dangers and risks of relocation while complying with human rights is also largely based on findings and analogies from DIDR practice.88 In response to the often negative results of resettlement, bilateral and MDBs – including the World Bank – have introduced binding standards, guidelines and complaint mechanisms, compliance with which is a prerequisite for project financing and lending.89 According to these standards, resettlement may generally only take place if all other alternatives have been ruled out (similar to the “last resort” principle). If involuntary resettlement is unavoidable, its scope as well as social and economic consequences should be kept to a minimum and compensated for by the accompanying development measures. The aim is to restore and, ideally, improve the living conditions of those affected in their new place of residence. To ensure this, comprehensive feasibility as well as environmental, health and socio-economic assessments are planned, in addition to monitoring and complaint mechanisms, such as the World Bank’s Inspection Panel.

Despite these standards, the track record of many development-induced resettlements has been poor. The main reasons for this are often the inadequate implementation of existing guidelines, weak national legal frameworks, limited government capacity and often misleading development promises. At the same time, top-down approaches often dominate, prioritising Western-influenced paradigms and external expertise while insufficiently accounting for local realities and indigenous knowledge systems. All these factors significantly impair the effectiveness and legitimacy of resettlement projects.90

A more development-oriented approach could both reduce climate and disaster risks and strengthen adaptation.

Decades of experience and extensive research on DIDR91 provide valuable insights for avoiding the repeating of mistakes that have led to injustices, and for better designing future relocations in the context of climate change.92 Some of these insights have already been incorporated into various guidelines for planned relocations in the context of disasters and climate change (see section “Relevant institutional processes, frameworks and guidelines”, p. 20). Nevertheless, both areas continue to be treated as strictly separate – politically and operationally – not least because development actors, especially development banks, have hardly been involved in climate change-related relocations (see section “International financing instruments” on p. 24). As a result, the implementation of planned relocations in response to climate change often lacks a clear development-oriented approach. However, experience from DIDR practice shows that relocations can contribute to sustainable development if they are designed as comprehensive development programmes. To meet this requirement, they must not only ensure physical safety, but also sustainably secure and improve the livelihoods of those affected. At the same time, it is important to address intersectional and structural problems – such as unequal access to resources – and to take into account the long-term nature of such processes.93 A stronger focus on development outcomes in the climate context could open up transformative pathways that both reduce disaster and climate change risks and enable more robust climate adaptation.

Status Quo of International Engagement

Given the complexity and resource intensity of planned relocations, affected communities and governments in many parts of the world are dependent on the support of international actors for their design and implementation, and are increasingly calling on them for assistance. However, an assessment of international engagement in the area of planned relocation to date shows that it has been fragmented and unsystematic, resulting in an inadequate alignment with identified demands.

Relevant institutional processes, frameworks and guidelines

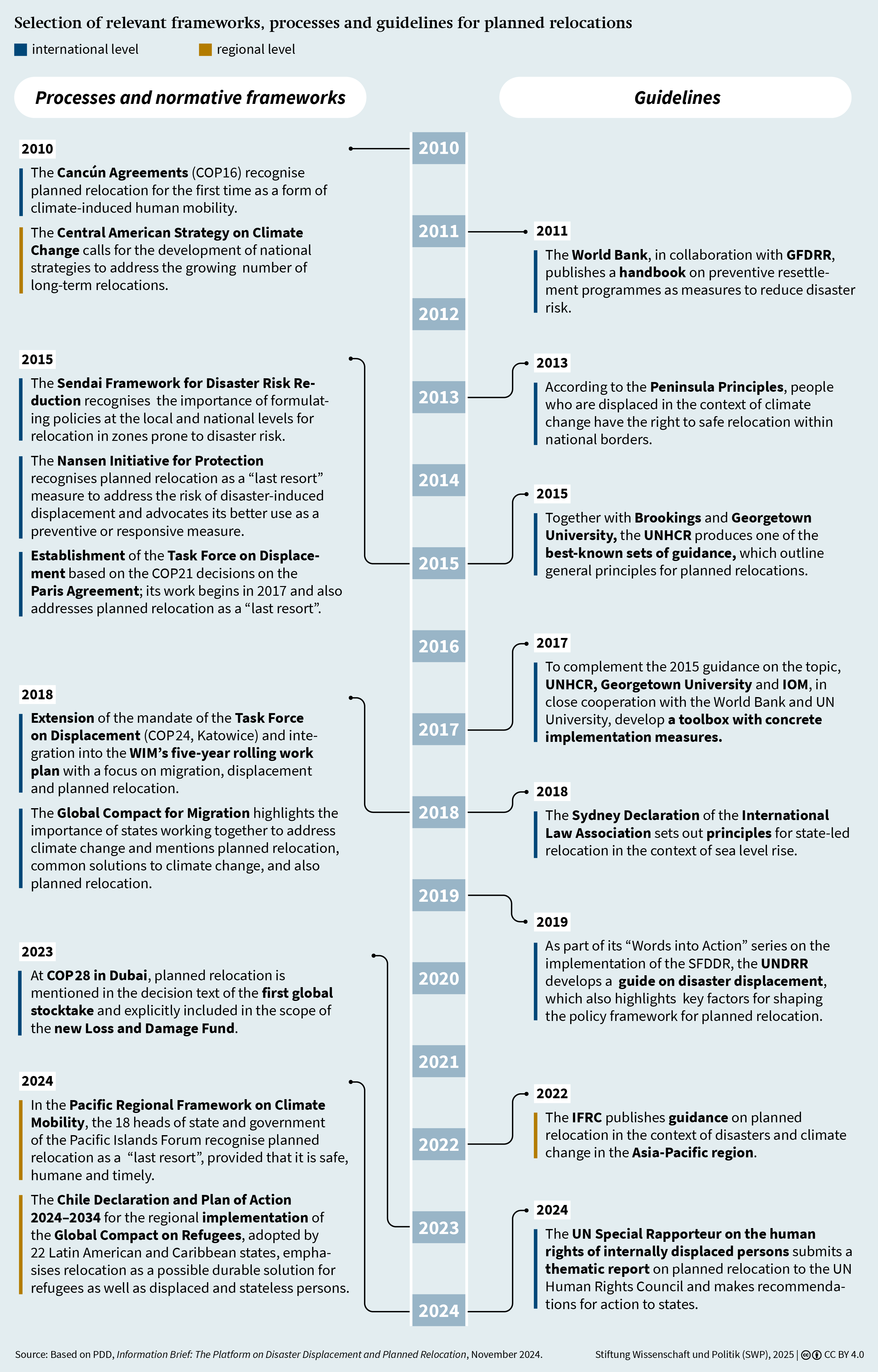

In 2010, the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC placed the issue of planned relocation on its agenda by calling for greater understanding of climate change-induced displacement, migration and planned relocation, and for increased cooperation in this domain.94 Since then, key climate and migration policy frameworks have recognised planned relocation as a relevant tool for disaster risk reduction, climate adaptation and for responding to loss and damage. These key documents include the COP decisions on the Paris Agreement,95 the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR)96 and the Nansen Initiative’s Protection Agenda97 for displaced persons in the context of disasters and climate change. The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM)98 also explicitly refers to planned relocation. Similar developments are also taking place at the regional level, for example in Central America, the Pacific region as well as Latin America and the Caribbean (see timeline, p. 21).

In these various policy areas (disaster risk reduction, climate adaptation, migration), relocation is predominantly understood as an adaptation measure to climate change and/or as a strategy to reduce the risk of displacement and disaster. Recently, relocation has also been increasingly discussed in the context of international climate negotiations regarding climate change-induced loss and damage: both as a cause and a consequence of loss and damage (see Info box 3, p. 26). For example, the Task Force on Displacement of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM) has included the topic of planned relocation in its ongoing work plan. The topic is also part of the technical support offered by the Santiago Network, which aims to facilitate access to technical knowledge related to loss and damage.99

International and regional frameworks (see timeline, p. 21) emphasise the need for safe, rights-based and durable solutions. They provide a normative reference point for shared responsibility and coordinated implementation of planned relocations by governments, international actors and relevant stakeholders. In some cases, they also call on national and local governments to develop appropriate public policies for planned relocations (see, for example, SFDRR 27 (k)).

To support the countries in question, various international (operational) actors have incorporated best practices and lessons learnt from previous relocation experiences (see section “Practical Insight: Challenges and Lessons Learnt”, p. 12) into policy, conceptual and operational guidelines. The 2015 Guidance on Protecting People from Disasters and Environmental Change through Planned Relocations100 – developed by the Brookings Institution, Georgetown University and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) – and the 2017 toolbox101 building on it was developed in collaboration with the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). These guidelines set out basic principles for protecting and safeguarding the rights of people affected by planned relocations, principles that have been incorporated into numerous other guidelines.

Instead of new international guidelines, existing ones should be adapted for local use, for example through practical, context-specific guidelines.

The guidelines listed in the timeline can provide valuable guidance for operational practices and normative principles for dealing with planned relocations. However, they are not legally binding and do not create internationally recognised standards against which participating states and other actors must measure themselves. Furthermore, they were mostly designed with the intention of claiming global, universal validity, with little involvement of countries. Due to specific local conditions, they are also often difficult to implement one-to-one on the ground. Their approach is also predominantly top-down; the needs, rights and autonomy of the affected communities, as well as non-economic losses and damage, receive too little attention. Issues of justice remain largely unaddressed. In addition, they are often only accessible to the affected communities to a limited extent. However, instead of drafting new guidelines at the international level or revising existing ones – such as the UNHCR’s 2015 guidance and the accompanying 2017 toolbox – the existing documents should specifically be made accessible to those applying them on the ground, for example by developing practical, context-specific guidelines that take into account local challenges, risks and needs.

In addition to the developments at the national level already described (see section “Developing national strategies and regulatory approaches”, p. 13), there are also efforts at the regional level to adapt the principles contained in the guidelines to specific contexts. In the Pacific region, for example, IOM and the PDD are currently assisting in the development of regional guidelines on planned relocations as part of the implementation of the Pacific Regional Framework on Climate Mobility, which was adopted by heads of state and government in 2023. Similar guidelines are being developed in the Americas, with a particular focus on gender and intersectionality. In addition, some communities have begun drafting their own local protocols, setting out what community-led planned relocation means for them in concrete terms and what support they need from governments and other actors. Examples include the Enseada da Baleia community in Brazil and communities such as Newtok in Alaska.102

Fragmented landscape of actors

As a cross-cutting issue, planned relocation affects various areas of cooperation within the international community – from climate adaptation and disaster preparedness/ disaster risk reduction to migration, human rights, development and reconstruction. Consequently, the international stakeholder landscape that advises and supports governments and affected communities in planned relocations is diverse. These include UN organisations, but also actors outside the UN system such as intergovernmental initiatives, international financial institutions, bilateral donors and NGOs. These actors offer various forms of support, ranging from financing and technical advice to operational guidance on implementation and capacity development. They also contribute to improving the evidence base by commissioning a large number of studies.103

Although none of the international organisations and NGOs has an explicit mandate to do so, some have expanded their work in recent years to include climate change-induced displacement and, in some cases, planned relocation.104 In particular, UNHCR, IOM, the World Bank and NGOs such as the Norwegian Refugee Council and Refugees International have actively contributed to the development of the aforementioned global guidelines (2015) and toolbox (2017) and have advocated for the issue to be included in global processes and frameworks.105 Many of these actors are also involved in the WIM Task Force on Displacement. In addition, IOM (in Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands) and the World Bank (in Jamaica and Uruguay) have supported governments in developing country-specific guidelines or strategies and offered capacity-building. For example, IOM conducted training for the Vietnamese government and published a training manual on planned relocations.106 More recently, it has created a regional Costing Tool for Funds for Latin America and the Caribbean to help governments and other stakeholders budget for relocation and, in particular, calculate non-economic losses and damage after disasters.107 The state-led PDD initiative, which is also involved in the WIM Task Force, has been working intensively on this issue since 2016, for example through political lobbying; the development and dissemination of international, regional and national guidelines and standards; and the promotion of research, data collection and the regional exchange of experience.108 With its new 2024–2030 strategy, the PDD has declared planned relocation to be one of its three key priorities.109

International support for climate-related relocation remains ad hoc, uncoordinated and fragmented.

Germany is one of the few donor countries that provides targeted support for planned relocation, albeit only in Fiji to date. On behalf of the BMZ, the GIZ has provided close support to the Fijian government from the outset in developing a comprehensive governance framework. This has included developing and implementing national relocation guidelines and SOPs, as well as establishing the CROC Trust Fund and the interministerial Fiji Taskforce on Relocation and Displacement. To strengthen the Fijian government’s institutional capacities, the GIZ also promotes training courses – for example on SOPs, the CROC Trust Fund, and climate risk and vulnerability assessment methodology – partly with the support of the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs.110 NGOs also have experience with relocation: In Fiji, the German NGO Brot für die Welt has been supporting a project on the island of Vanua Levu since 2022. The relocation affects 160 residents of the village of Cogea, which was devastated by Cyclone Yasa in 2020.111

Nevertheless, there is still no central point of contact at the international level for national governments and communities seeking guidance on planned relocations. None of the international organisations has a recognised leadership role; rather, various actors take the lead in different country-specific contexts, often based on existing partnerships. The result is a fragmented support landscape with widely varying approaches, standards, and references to existing guidelines and human rights. Bower and Harrington-Abrams (2024) refer to this as an institutional missing link, the absence of which meaning that international support for climate change-induced relocation is largely ad hoc, uncoordinated and isolated, carrying the risk of duplication, inefficient use of limited resources and competition. Furthermore, in the context of climate change-induced relocation, there are no institutional mechanisms (whether rights-based or otherwise) to hold the international actors involved accountable for their actions. This is particularly problematic given the negative track record of, for example, MDBs in the area of development-induced displacement and resettlement (DIDR, see section “Learning from development-induced resettlement contexts”, p. 18). Instead, the degree of compliance with international guidelines such as the UNHCR guidance and the IOM toolbox or internationally agreed standards (e.g. human rights principles) varies greatly.112 There is also no comprehensive overview of the various actors’ activities, their priorities, who is working with whom and where, and which structures are particularly effective.113

Current international engagement is predominantly focused on technical advice rather than on the concrete implementation or financing of climate change-related relocation projects. Development actors in particular have been largely absent at the project level and in implementation.114 A few exceptions include, for example, the support provided by IOM for relocation programmes following the 2007 floods in Mozambique and that provided by the GIZ and the EU for the relocation of the villagers of Narikoso in Fiji. The experience gained from the latter project was incorporated into the development of the Fijian relocation guidelines. The measure and its implementation are considered a pilot for further projects in the Pacific region (see Info box 2, p. 14).115

International financing instruments

Fragmentation in the international processing of planned relocations also extends to the level of external financing: Bilateral, regional and multilateral donors, UN organisations and even the EU often only cover individual phases or components of the relocation process. Funds are frequently allocated solely for the construction of housing and public infrastructure, whereas measures to promote socio-economic well-being and provide psychosocial support are rarely taken into account. In addition, the funds are usually project-related or earmarked – and insufficient overall.116 This makes long-term, cross-sectoral planning difficult, even though it would be necessary to overcome the many challenges before, during and after relocation.117

MDBs in particular have only been involved in financing to a limited extent, even though they are capable of mobilising the considerable resources required and strengthening national ownership of inclusive relocation policies. This is due to the reluctance of national governments to take out loans or use limited grants to address the impacts of climate change, which has primarily been caused by industrialised nations. The risk aversion of banks also plays a role in their reluctance to deal with complex land tenure issues and the numerous other challenges that have been already described.118

UNFCCC funds such as the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and, in particular, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) could also theoretically finance planned relocation measures as part of climate change adaptation efforts, even if this task is not explicitly mentioned in their strategic plans. However, this has only happened in a few isolated cases so far: The GCF and the AF have supported projects with relocation components in Rwanda and Senegal. With around US$23.4 billion119 (as of June 2025), the GCF has significantly more funds at its disposal than the LDCF (US$2.25 billion, as of September 2024) and the AF (US$2 billion, as of March 2025).120 This makes it the most likely fund to support costly relocation.121 However, the new Adaptation Gap Report 2025 from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) also shows that funding for adaptation measures remains consistently inadequate, overall.122

Only the mandate of the new Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage explicitly includes migration, displacement and planned relocation.

The newly established Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) is the only UNFCCC fund whose mandate explicitly includes support in the areas of migration, displacement and planned relocation. However, its current level of funding, at just under US$583 million123 (as of October 2025), is extremely low; the pledges made to date of US$788.8 million (as of June 2025)124 fall far short of the estimated annual requirement of US$400 billion.125 It also remains to be seen how the fund will respond to growing demand and manage competing priorities, given its severely limited resources.126 It also remains unclear whether countries will prioritise planned relocations in their FRLD applications and how quickly and effectively these funds will reach the affected communities.127

There are also smaller funds such as the Mayors Migration Council’s Global Cities Fund on Inclusive Climate Action, which is itself funded by private foundations – the Ikea Foundation and the Robert Bosch Foundation. For example, it co-financed the relocation of 140 internally displaced households in Hargeisa (Somaliland)128 and 15 families in Beira (Mozambique),129 two of the few climate change-related relocation projects in Africa. The Climate Justice Fund, financed by the Scottish government and several philanthropists, aims to strengthen the capacities of particularly affected communities – especially women, young people and Indigenous groups – so that they can develop and implement their own solutions to improve their climate resilience. The fund has awarded grants to local communities in places such as Alaska and Bangladesh that are considering relocation, are in the process of relocation or are dealing with the consequences of relocation that has already taken place.130

Another example is the newly established Community Climate Adaptation Facility (C-CAF), led by the Global Centre for Climate Mobility (GCCM). The facility is based at the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) and is funded by UN organisations, governments and philanthropic foundations. It is designed to provide quick and easy access to funding for amounts lower than €100,000 for local communities’ adaptation efforts, which in the future will also enable community-led relocation measures to be financed. At the same time, there is a risk that duplicate structures and competition for funding could arise, for example in Fiji, where there is already a community-based trust fund for relocation, but which has received hardly any international funding (including from Germany). Nevertheless, C-CAF could fill a key gap in international climate finance: Many existing funds have excessively high minimum amounts and complex application requirements, rely heavily on government implementation or are too slow to respond. This results in long waiting times for disbursement and makes direct access difficult for local communities.131

|

Planned relocations can be a form of climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, or a form of loss and damage. For example, while relocation from areas increasingly exposed to extreme weather events is a measure of adaptation to climate change, the numerous negative effects associated with relocation can be considered material and non-material losses and damage.a This categorisation is particularly important with regard to UNFCCC financial flows. Depending on how relocation is classified, different institutions, implementation procedures and operational responsibilities apply. Among other things, there is a risk that classifying planned relocation as loss and damage could mean that communities wishing to relocate only gain access to assistance once their situation has become critical or life-threatening. This delay prevents proactive relocation support and can lead to significant but avoidable loss and damage, or lead to affected populations undertaking the relocation process on their own, without the necessary support and resources to achieve a sustainable outcome.b a Huckstep and Clemens, An Omnibus Overview (see note 31), 30. b Gini et al., “Navigating Tensions” (see note 21), 1264. |

At the same time, the FRLD represents a new source of funding that explicitly extends support for all forms of climate change-related mobility, including planned relocation, and has received considerable political attention – even though compensation or redress for climate change-related damage remains one of the most politically controversial and sensitive aspects of international climate finance. Nevertheless, developing countries’ demand to anchor “loss and damage” as a separate sub-goal in the new climate finance goal – the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) – failed. Thus, the financing of loss and damage falls outside the NCQG mandate and there is no direct obligation to provide such financing.c Researchers increasingly argue that planned relocations are both adaptation and loss and damage, and that the strict separation between the two concepts makes it considerably more difficult to plan adequate relocation measures in practice.d c Laura Schäfer et al., “Climate Policy in Times of Crisis: Weak Compromises despite Urgent Needs”, Germanwatch (blog), December 2024. d See Karen E. McNamara et al., “The Complex Decision-Making of Climate-Induced Relocation: Adaptation and Loss and Damage”, Climate Policy 18, no. 1 (2018): 111–17. |

|

The funding cuts jeopardise both technical and financial support measures and the existence of established multi-stakeholder initiatives.

Sustainable International Engagement

Advancing climate change is significantly increasing the pressure on affected communities and governments and narrowing the window of opportunity to create the appropriate political, legal and financial frameworks for dealing with planned relocations. The longer that adequate structures remain lacking, the greater the risk that human security will be massively threatened, fundamental human rights violated and entire communities displaced. Governments must therefore not wait until a disaster strikes and act proactively. Early planning significantly reduces costs and damage – a crucial factor in view of dwindling resources.

This requires more coordinated, cooperative and accountable support across different policy areas. The aim must be to provide (non-)state actors with easy access to resources and expertise while strengthening the leadership and autonomy of the communities affected. In addition to better coordination and a more coherent approach to the engagement of international actors, open, collaborative learning processes are essential to ensure that political and technical experiences in relocation practices are effectively exchanged.132

Germany can play a key role in this regard. German development cooperation has already gained valuable experience in Fiji and made a decisive contribution to the creation of a comprehensive governance framework for planned relocations, which is now regarded as a model worldwide. Such initiatives are an important start. However, they are not sufficient to address the growing importance and complexity of the issue. What is needed now is a long-term, inter-ministerial commitment by Germany in the area of planned relocation that closes existing gaps in the international system and sets standards for responsible, human rights-based and development-oriented climate adaptation.

Preconditions for effective international support

Given the profound impact on those affected, the conflict-ridden domestic dynamics and the often negative experiences with relocation, the key question is when and under what conditions international support should be provided. The following basic preconditions can be derived based on the findings to date (see section “Practical Insight: Challenges and Lessons Learnt”, p. 12).

Multidimensional approach

To effectively address the complex risks and challenges of relocation, there is a growing need for a multidimensional support approach that integrates existing instruments of disaster risk reduction, climate adaptation, humanitarian aid and development cooperation and ensures multi-sectoral cooperation (see “Action field 1: Supporting cross-sectoral cooperation”, p. 29). Based on previous relocation/resettlement experiences, scientific findings and lessons learnt from other resettlement contexts (see section “Learning from development-induced resettlement contexts”, p. 18), the purpose of relocation should not be solely to protect against climate risks. The long-term enhancement of the well-being of those affected, their resilience to future climate hazards and the reduction of structural inequalities are equally important – with the overarching goal of promoting sustainable development and social justice.133 From this, four (partly overlapping) normative principles that should be prioritised in the design and support of relocation processes (see Info box 4) can be drawn.134

Consent as a prerequisite

As a general rule, the following should apply to the support of planned relocations: If those directly affected have not given their consent, the utmost restraint is required. International actors should only promote planned relocations if the relocation is either expressly desired by the communities affected or implemented with their voluntary, informed consent. Such an approach would be based on the right of Indigenous Peoples to consultation and consent with regard to their land, culture and resources – a right recognised in international law and firmly established in the extractive industries and the design of sustainable supply chains, among other areas.135 It is crucial that those affected are free to choose whether they want to relocate or pursue other adaptation measures. Community-led relocations should therefore be given priority. If consent cannot be obtained despite comprehensive consultation, relocations may only be carried out to protect lives – on the basis of national law and in accordance with international standards.136

Governments’ interest in climate adaptation should not take precedence over the human rights of those affected. Major investments should only be made once it is certain that the communities actually want to be resettled. Otherwise, there is a risk of financing measures that violate human rights and are unlikely to succeed. In authoritarian and fragile contexts, where democracy and freedom of expression are not guaranteed, government-initiated relocations should be supported with the utmost caution – and only if adequate safeguards are in place and the measures demonstrably serve to protect lives and improve people’s well-being.

Relocation as a “last resort”

Against this backdrop, it is crucial that international actors take a differentiated approach to consultation and do not rush to promote relocation as the preferred solution. Rather, relocation should be understood as a “last resort”. Regardless of how well-planned and implemented, relocation always entails certain losses and damage for the people affected. The risks and negative consequences of relocation measures must therefore always be carefully weighed up, which means that less disruptive options such as dykes, early warning systems and local adaptation strategies (e.g. income diversification or informal support systems through remittances from family members abroad) should be examined in advance. Such approaches can enable communities to remain in place even under difficult environmental conditions.137 In other cases, voluntary, safe and regular migration across borders – for example, within the framework of regional free movement of persons, targeted labour migration or humanitarian visas – may be a more humane and sustainable adaptation option. Migration should therefore not be perceived as a failure of adaptation, but as a legitimate, independent strategy for risk reduction and development. Corresponding regional agreements on the free movement of persons have already been established in the Pacific and the Caribbean.138 However, there are also cases in which communities prefer relocation within their own country, despite the existence of alternatives; in these situations, the principle of “last resort” no longer applies.139

Starting points for the German Federal Government

In view of climate change, without support for low-income countries from wealthy industrialised nations such as Germany, there is a threat not only of humanitarian disasters and the displacement of entire communities, but also of significant setbacks in the fight against poverty. Climate impacts can also destabilise entire regions, increase the likelihood of conflicts as risk multipliers and disrupt global supply chains. Supporting particularly climate-vulnerable partner countries – such as the Pacific Island states or countries in sub-Saharan Africa – in their efforts to adapt to climate change and cope with loss and damage is therefore not only an urgent obligation in the context of global climate justice, but also crucial for international and national security.

Despite its own budget cuts, Germany, as one of the leading donors in climate and development finance, can help to close existing international gaps and deficits in coordination, accountability and access to financial resources and expertise in the area of planned relocation (see section “Status Quo of International Engagement”, p. 20). To this end, the German government should focus its engagement in the areas outlined below in a targeted and strategic manner.

Action field 1:

Supporting cross-sectoral cooperation

|