Sovereign Wealth Funds and Foreign Policy

How Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar Invest in Their Power

SWP Research Paper 2026/RP 03, 04.02.2026, 31 Seitendoi:10.18449/2026RP03

ForschungsgebieteDr Stephan Roll is a Senior Fellow in SWP’s Africa and Middle East Research Division.

-

Five of the world’s most active and largest sovereign wealth funds are to be found in the Gulf Region: the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and the United Arab Emirates’ Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), Mubadala and ADQ.

-

These funds not only serve to convert oil revenues into investment capital, thereby enabling the transition from rent-based to more diversified economies; they also contribute to expanding the foreign policy capabilities of the countries in which they are based.

-

Institutional and personnel linkages enable the Saudi, Qatari and UAE governments to deploy their funds strategically, which, in turn, allows them to significantly expand their hard, soft, and sharp power – for example, through domestic and foreign investments in sectors such as armaments, media, sports and new technologies as well as through cooperation with politically influential actors. At the same time, the Gulf monarchies seek to portray their sovereign wealth funds as apolitical and purely profit-oriented – a narrative that is facilitated by the establishment of subsidiaries or cooperation with private equity firms.

-

Understandably, Germany and its European partners have an interest in attracting sovereign wealth funds as investors, but they must not overlook the risks involved. These include third parties gaining access to critical infrastructure, sensitive military and security technology being leaked and the Gulf monarchies exercising political influence.

-

Further, Germany and the EU must take a more fundamental look at how the three Gulf monarchies have increased their foreign policy options through the sovereign wealth funds. This is important as the actions of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar – at both the regional and international level – are at times contrary to German and European interests.

Table of contents

Issues and Recommendations

Sovereign wealth funds are playing a central role in the economic development of the three Gulf monarchies of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar. They serve as key financing and governance instruments in the transition from oil- and gas-based rentier towards more diversified economies. At the same time, as is increasingly emphasised by the research on sovereign wealth funds, they are not merely economic actors but can also be used to advance the foreign policy objectives of the respective states. In the three Gulf monarchies, this is evident from the personnel overlap between those managing the funds and those directing domestic and foreign policy. However, owing to the largely opaque decision-making processes within the funds, it is often difficult to clearly distinguish between the economic and foreign policy motivations of certain investments. To assess the foreign policy significance of sovereign wealth funds, this study focuses on the power resources of the Gulf monarchies. Based on the region’s most active sovereign wealth funds – which are sometimes referred to as the “Oil Five” – it examines the extent to which their activities enable the respective states to exercise hard, soft and sharp power. The five funds are the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and the Emirates’ Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), Mubadala and ADQ.

The analysis shows that the Gulf monarchies are successfully using their sovereign wealth funds to translate oil revenues into foreign policy clout across all three dimensions of power – hard, soft and sharp. For the most part, the funds do not function as direct instruments of foreign policy. Rather, they increase the respective country’s scope for external action by investing in sectors such as the arms industry, media, sports and new technologies and by engaging in targeted cooperation with influential actors. At the same time, the funds seek to ensure that their political ties remain as far below the radar as possible. To this end, investments in foreign markets are made via private equity or venture capital vehicles, while engagements that could provoke criticism domestically – such as extensive investments in Israel – take place away largely out of range from public scrutiny.

For Germany and its European partners, these capital-rich sovereign wealth funds are extremely attractive, as they offer considerable investment potential, high liquidity and, in most cases, a long investment horizon. They create opportunities to finance large-scale infrastructure projects, to strengthen the financial basis of companies in strategic sectors and to gain access to markets in the Gulf region. However, the close links between these funds and the foreign policy agendas of the respective countries present a twofold challenge for Germany and the European Union.

On the one hand, investments by these funds in the European market entail the risk of critical infrastructure being taken over and, even more serious, knowledge and technology being transferred in a targeted manner. This is significant not just because of potential competitive disadvantages for European companies. It also poses the threat of sensitive technologies being transferred to third countries such as China and Russia, where sovereign wealth funds are similarly active, as well as to the three Gulf monarchies themselves. Particularly problematic would be scenarios in which new technologies contribute to the strengthening of the capacities for surveillance and repression of the authoritarian leaderships in those three countries. This means that such risks must be subject to careful investment screening. And that is no easy task, especially in the case of investments channelled through complex investment vehicles and private equity firms.

On the other hand, the sovereign wealth funds are enabling Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar to pursue an increasingly active foreign policy. At both the international and regional level, there are times at which their actions are at odds with German and European interests – for example, in climate negotiations, in dealings with Russia and in conflicts such as that in Sudan. What is required, therefore, is a coordinated foreign policy towards the three countries that systematically integrates both foreign-policy and economic interests. Germany and its European partners should bear in mind that the European Economic Area is particularly attractive for the sovereign wealth funds of the Gulf monarchies owing to its size and stability, not least against the backdrop of the uncertain situation in the United States under President Donald Trump. The investment interests of those funds, which do not constitute a unified actor and may even be in competition with one another, should therefore be leveraged in a targeted manner to more clearly articulate and more effectively realise Germany’s own interests. In this way, Europe’s ability to act vis-à-vis the Gulf monarchies would be strengthened.

Introduction: Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds in Transition

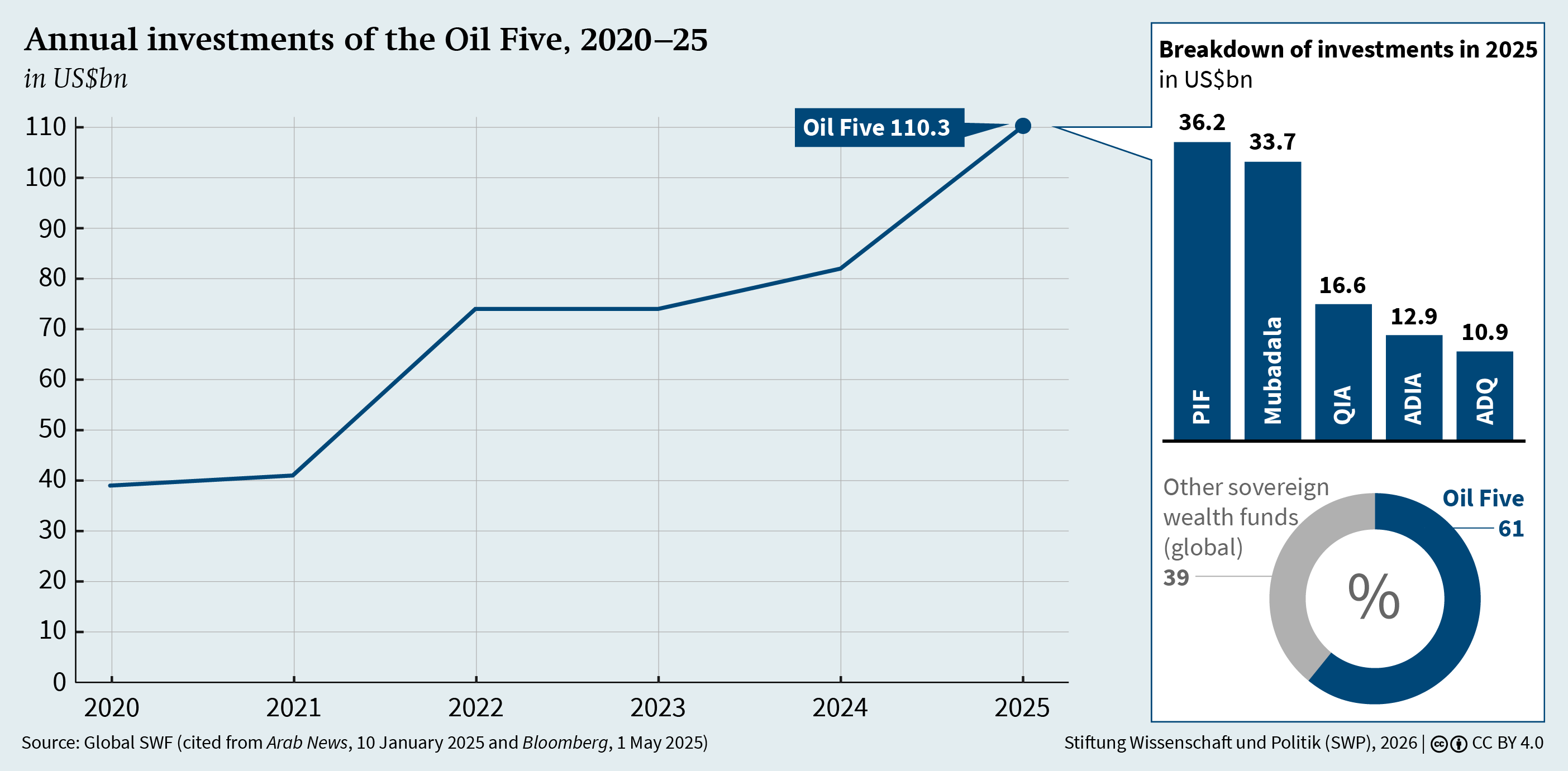

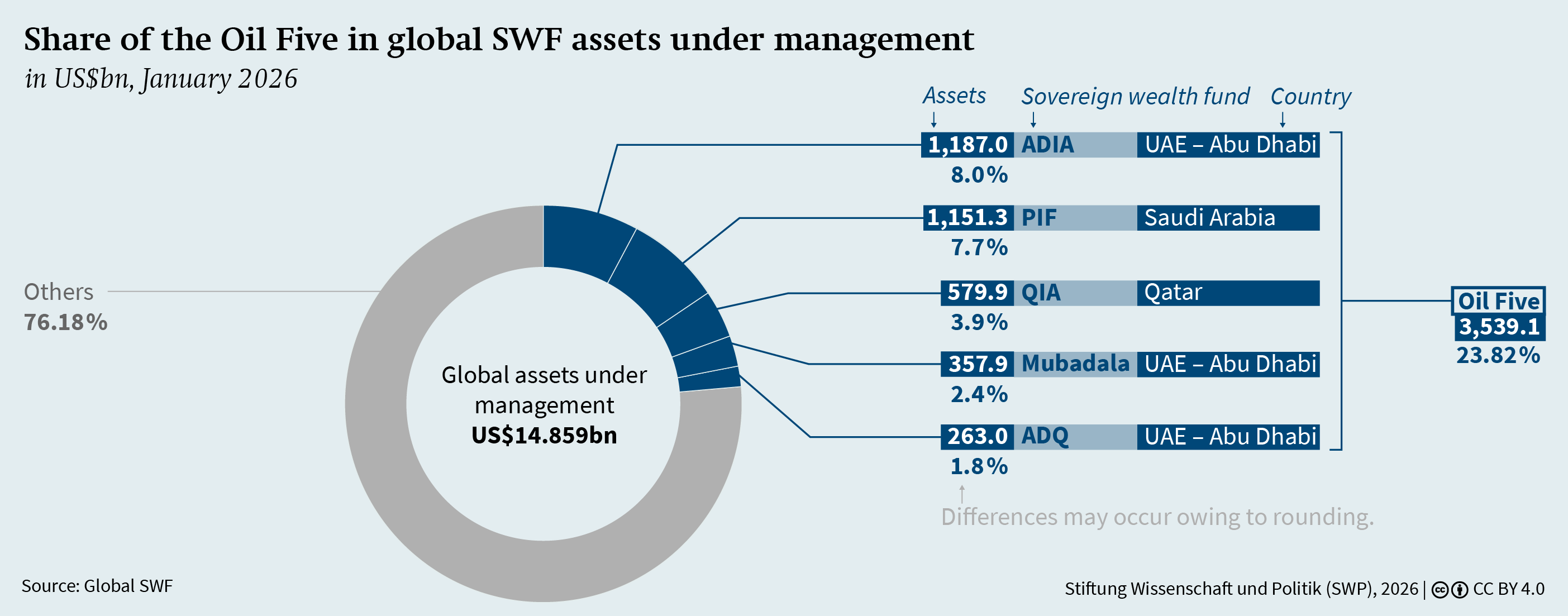

In 2024, the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and the Emirates’ Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), Mubadala and ADQ all ranked among the world’s 10 most active sovereign wealth funds1 for the third consecutive year. Collectively referred to as the “Oil Five”, these funds accounted for around 61 per cent of the total investment volume – some US$180.3 billion – of the 100 or so sovereign wealth funds around the globe (see Figure 1, p. 8).2 The five’s combined investment volume of over US$110 billion was more than the total public investment made by the German government in 2025 (€86.8 billion).3 With combined assets of around US$3.5 trillion, they control nearly a quarter of the total asset value of sovereign wealth funds worldwide, which is currently just under US$15 trillion (see Figure 2, p. 9). However, their rise to prominence in international capital markets has been gradual, having begun more than two decades ago.

Until the 1990s, the investment approach of the four wealthiest Gulf states – Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait – was predominantly conservative: their budget surpluses from oil and gas exports were invested mainly in fixed-income securities, above all, US government bonds. The objective was to build up assets in order to secure revenues over the long term, cushion fluctuations in commodity cycles and prevent so-called Dutch disease (that is, the loss of competitiveness in other sectors resulting from an appreciation of the domestic currency). Moreover, petrodollar recycling served to consolidate the alliance with the four countries’ most important security partner – the United States.4

From the 2000s onwards, the Gulf monarchies gradually adjusted their investment strategies. Owing to the sharp rise in oil prices between 2002 and 2008, revenues from hydrocarbon exports significantly exceeded government expenditure. As a result, government savings rates increased markedly to reach an average of around 40 per cent in 2007, albeit with that share differing widely between individual countries.5 This development led both to large capital inflows into existing sovereign wealth funds and the establishment of new such funds. Even when the savings rates declined after 2007 the funds’ assets continued to grow and were increasingly channelled into corporate investments, infrastructure projects and alternative asset classes. Sovereign wealth funds thereby evolved from instruments geared primarily towards savings and macroeconomic stabilisation into vehicles with an explicit developmental orientation. In contrast with the Kuwaiti sovereign wealth fund, the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), which to this day serves mainly as an international portfolio investor and thus remains closer to the classic model of a sovereign wealth fund, the Saudi, Qatari and UAE funds have become active strategic investors. They have expanded their direct corporate investments and now exercise greater influence over the strategic orientation of the companies in which they hold stakes.

Saudi Arabia, by contrast, was a latecomer in developing a sovereign wealth fund with a significant international profile. Until roughly a decade ago, the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) in effect performed this role through its reserve and investment portfolio, which was managed in a predominantly conservative manner and invested mainly in fixed-income securities, especially US government bonds. It was only in 2015 that the kingdom transformed the Public Investment Fund (PIF) – at the time a largely obscure state investment vehicle – into a modern sovereign wealth fund and endowed it with substantial capital. Since then, PIF has expanded rapidly to surpass the assets managed by SAMA. With around 76 per cent of its total assets under management invested in Saudi Arabia as of 2023,12 PIF is significantly more active in the domestic economy than the funds of the two neighbouring countries. At the same time, it holds significant stakes in international companies such as the ride-hailing service Uber and the electric vehicle manufacturer Lucid Motors,13 through which it is able to exercise influence over the strategic decisions taken by those companies.

The governments of the three Gulf monarchies cite predominantly economic reasons for shifting their investment focus from conservative, passive strategies towards higher-risk holdings in both domestic and foreign companies. The overarching objective is to fundamentally diversify their economies and reduce their one-sided dependence on oil and gas revenues – an ambition clearly reflected in the development plans through which all three states have articulated their respective “visions” for 2030.14 Thus, sovereign wealth funds not only have the task of building up state reserves for the future and protecting national budgets against fluctuations in commodity prices and external shocks. They are also intended to serve as instruments of targeted investment aimed at strengthening national competitiveness and attracting foreign capital and expertise to the domestic economy.

However, it is questionable whether this can explain in full the investment behaviour of the Oil Five. Media reports and think tank analyses repeatedly point to their role as an instrument for exercising political power,15 whether to secure regime stability16 or as a means of chequebook diplomacy.17 Experts from within the Gulf states highlight the political significance of these funds, too. The well-known Emirati political analyst Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, for example, emphasises that ADQ and Mubadala have not only an investment-related but also a distinctly political dimension.18

For their part, the governments of the Gulf states seek to counter this perception through their public communications and voluntary commitments. In 2008, Abu Dhabi published an open letter in The Wall Street Journal that was addressed to regulatory authorities and political decision-makers in the United States and Europe in the wake of criticism of investments made by Arab sovereign wealth funds in Western financial institutions during the global financial crisis. In the letter, the emirate disclosed its investment guidelines and asserted that it had never used sovereign wealth funds as instruments of foreign policy, nor would it do so in future. At the same time, it emphasised its commitment to maintaining appropriate standards of governance and accountability.19

In the same vein, ADIA, Mubadala, QIA and PIF have all committed themselves to the Santiago Principles, which were developed in 2008 by the International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds with the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The principles aim to strengthen confidence in sovereign wealth funds and establish uniform standards for transparency, governance and risk management.20 Among other things, they stipulate that a fund’s investment strategy should be implemented independently of its operational management and within a framework of clearly defined responsibilities. However, given that the sovereign wealth funds in the three Gulf states are closely intertwined with the respective political leaderships – both institutionally and in terms of personnel – the credibility of such voluntary commitments remains doubtful.

Institutional and Personnel Linkages between Sovereign Wealth Funds and Foreign Policy

Since Saudi Arabia and Qatar are absolute monarchies and Abu Dhabi – the dominant emirate within the UAE – is similarly governed by an hereditary ruler (emir) who exercises what is, in effect, unlimited authority, their respective sovereign wealth funds ultimately fall under the control of the head of state. They are not subject to parliamentary oversight, and their supposed operational independence in investment decisions exists largely on paper only. This sets them apart from sovereign wealth funds in democratic states, such as the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, which is managed by Norges Bank Investment Management and subject to rigorous democratic oversight. In Qatar and Abu Dhabi, QIA, ADIA, ADQ and Mubadala are subordinate to the respective Supreme Council, which is headed directly by the ruler of the country – i.e., Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani and Emir of Abu Dhabi and President of the UAE, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.21 In this capacity, the two appoint the members of the funds’ governing bodies. In Saudi Arabia, the board of directors (BoD) of PIF is installed by royal decree and supervised by the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA), whose members are also appointed by the king. But the links between sovereign wealth funds and foreign policy derive not only from the person of the respective ruler, who, ultimately, makes the country’s political decisions; they extend well beyond this, reflecting deeper institutional and strategic entanglements.

In Saudi Arabia, the chairmanship of both the PIF’s BoD and the CEDA is held by Crown Prince and Prime Minister Mohammed bin Salman, who, owing to his father’s age and health, is widely regarded as the country’s de facto ruler and the central driver of its foreign policy. At the same time, he exercises direct influence over PIF’s operational activities,22 which are managed by his close confidant Yasser al-Rumayyan. Al-Rumayyan is currently the most influential manager within the kingdom’s public economic sector. In addition to serving as governor of PIF, he chairs the state-owned oil company Saudi Aramco. He appears to have ministerial rank and plays a central role in foreign policy, including Riyadh’s relations with China.23 The personnel links between PIF and the country’s foreign policymaking centre are further strengthened by the Saudi Centre for International Strategic Partnerships (SCISP), which is tasked with “harmonising and coordinating all the Kingdom’s efforts relating to its international strategic partnerships with partner countries”.24 Although the importance of the SCISP for specific policy decisions should not be overestimated, it does provide a forum where influential members of Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy establishment come together, with six of the 12 SCISP board members also sitting on the PIF board.25

In Abu Dhabi, operational responsibility for the sovereign wealth funds was reorganised within the ruling family in 2023. When Mohammed bin Zayed, who had been considered the de facto ruler for years, was officially named emir of Abu Dhabi and president of the UAE following his brother’s death in 2022, he relinquished direct control of the sovereign wealth funds. That task was transferred to two of his brothers – Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, who became chairman of ADIA and ADQ, and Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, whom he appointed CEO of Mubadala.26 The reshuffle further consolidated the influence of the so-called Bani Fatima (descendants of Fatima), a group of five full brothers, including the emir himself, that is named after their mother.27 Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, another full brother, has been managing director of ADIA since 2010 and also sits on ADQ’s BoD. Moreover, two of Mohammed bin Zayed’s sons hold board positions at ADIA and Mubadala.

The Bani Fatima family not only exercises control over Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth funds but also plays a central role in shaping the UAE’s foreign and security policy.28 Alongside Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan, there is another full brother, Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, who plays a particularly pivotal role. In addition to serving as chairman of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and ADQ, he has held the post of national security adviser since 2016 and is thus the de facto head of the Emirates’ intelligence apparatus. The close interlinkage between sovereign wealth funds and foreign policy also extends beyond the ruling family itself. For example, Khaldoon Khalifa Al Mubarak, who serves as managing director and group CEO of Mubadala Investment Company, is simultaneously chairman of the Executive Affairs Authority – a government body that provides strategic policy advice to Mohammed bin Zayed– and presidential envoy to China.29

In Qatar, there was a similar close intertwining between the management of the Qatar Investment Authority and the country’s foreign-policy leadership following the establishment of the fund in 2005. Until 2013, responsibility for the running of the fund lay with Hamad bin Jassim Al Thani, who simultaneously served as CEO of QIA and foreign minister; later, he also held the office of prime minister. He is widely regarded as the architect of Qatar’s ambitious and proactive foreign and regional policy under Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the father of the current ruler.30 Following Hamad’s abdication in 2013 and the accession of Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, the personnel overlap between the sovereign wealth fund and the foreign-policymaking centre remained intact initially. Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, who has been foreign minister since 2016, served simultaneously as chairman of QIA for several years; but this dual role came to an end when the fund’s management was reorganised in 2023. At that point, Bandar bin Mohammed bin Saoud Al Thani, a seasoned economic manager who is also governor of the central bank, was appointed to head the fund. The composition of the current BoD no longer reveals any direct personnel links to the foreign policymaking core. It is likely that oversight is now ensured, above all, by Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the fund’s deputy chairman and a full brother of the emir, who ranks among his closest advisers.31

Expansion of Foreign Policy Options

The institutional and personnel overlaps between the sovereign wealth funds and the foreign policymaking centres of the three countries indicate that these funds are not exclusively profit-oriented. Recent conceptual research on sovereign wealth funds further supports that view.32 A growing body of scholarship emphasises that such funds may pursue political or normative objectives alongside financial returns. This insight also applies in democratic contexts: a case in point is Norway’s GPFG, through which Oslo has promoted social norms and environmental standards by means of shareholder activism.33 However, existing research suggests that in autocratic systems, low levels of transparency and the absence of robust institutional oversight mechanisms create greater scope for the political instrumentalisation of sovereign wealth funds.34 In such settings, the funds can be used both as a means to consolidate the ruling elite’s grip on power35 and as instruments of economic statecraft, whereby such tools are deployed in a targeted manner to advance national interests vis-à-vis those of other states and international actors.36

At the same time, there are significant doubts about whether sovereign wealth funds are, in fact, being systematically employed for foreign policy purposes. Some authors regard such concerns as fundamentally overstated and point to the paucity of empirical evidence.37 They argue that instrumentalising the funds for foreign policy objectives would undermine return maximisation and, in the long run, erode the political leaderships’ capacity to provide the welfare benefits that, historically, have contributed to regime stability.38 Moreover, the limited transparency of most sovereign wealth funds complicates efforts to reconstruct decision-making processes and identify the motives underlying individual investments.39 It is true that the proverbial “smoking gun” – in this case, direct evidence of the deliberate instrumentalisation of individual investments – is difficult to find. In many cases labelled as “political”, it is unclear whether the investment decisions are driven ultimately by foreign policy considerations or by the expected financial returns. Even where foreign policy instrumentalisation is evident, the question remains as to what extent such individual cases allow inferences to be drawn about future behaviour. Conversely, it must also be asked whether a return-oriented investment strategy can, in itself, allow the conclusion to be drawn that foreign policy motives will not play a role in future.

Sovereign wealth fund investments can create strategic room for manoeuvre or create dependencies that may later be leveraged for foreign policy purposes.

For this reason, the focus of the following discussion is not to establish the degree to which individual investments pursue specific foreign policy objectives but to examine the structural dimension of sovereign wealth funds. The aim is to clarify the extent to which the Oil Five expand the foreign policy options of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar in the medium to long term. The analysis looks at how sovereign wealth funds contribute to strengthening the hard, soft and sharp power of the three countries. According to the definition of Joseph Nye, hard power denotes an actor’s ability to influence others through coercion or economic inducements, whereas soft power is based on attractiveness, persuasion and cultural appeal.40 Sharp power is a concept introduced by the National Endowment for Democracy that is applied to authoritarian states and initially was used, above all, in connection with China and Russia. It refers to manipulative forms of exercising influence that target public discourse, political processes and economic structures with the aim of undermining and destabilising open societies.41

Sovereign wealth funds can employ their investments across all three dimensions of power in order to make strategic room for manoeuvre or create dependencies that may later be leveraged for foreign policy purposes. To some extent, this can occur through purely return-oriented investments as well: by strengthening the economic capabilities of the state, the fund contributes to maintaining or expanding the state’s relative power vis-à-vis other countries.42 However, there are also investments in which a focus on financial returns is more directly combined with the reinforcement of one or more of the three power dimensions. And it is clear that some investments are geared primarily towards expanding foreign policy capabilities, whereby economic considerations play a subordinate role only.

Hard power

In order to increase their economic hard power, it is conceivable that governments could use sovereign wealth funds in such a manner that other states are rendered economically dependent.43 To this end, sovereign wealth funds could acquire stakes in strategic industries or critical infrastructure so as to obtain leverage over the target country. Such holdings could be used to influence corporate decision-making or, in extreme cases, to threaten capital withdrawal to the detriment of the host economy. The three Gulf monarchies have the economic potential to pursue such an approach, as the example of the European banking sector clearly illustrates. The sovereign wealth funds of the UAE and Saudi Arabia alone would be sufficiently large to acquire qualified majorities in systemically important banks within the Eurozone, allowing them to gain political influence not only at the national level but also across the region.44 Even investments already made could be regarded as systemically relevant and may have increased the scope for exercising political influence. Illustrative examples include earlier investments by PIF in the US startup ecosystem45 and the involvement of QIA in the British, and particularly the London, real estate market.46

However, exploiting sovereign wealth fund investments in this way presents considerable challenges. First, there would likely be significant – not least regulatory – resistance in the target countries. Second, the sheer size of sovereign wealth funds does not mean that their assets are readily available in liquid form and can thus be easily mobilised for short-term investments of systemic relevance – for example, in the European banking sector. Third, if used on a large scale for hard power purposes, sovereign wealth funds would likely sustain significant opportunity costs in the form of foregone returns and reduced portfolio performance. Central bank deposits have, in fact, been far more relevant as instruments of economic power. In 2016, Saudi Arabia threatened to sell US government bonds and other assets in order to prevent the US Congress from passing legislation that would restrict state immunity.47 Similarly, in 2024 Riyadh reportedly hinted that it would sell European bonds should the Group of Seven proceed with the seizure of Russian assets.48 Central bank deposits also served as leverage during the Arab Spring,49 particularly in Egypt, where billions of US dollars from Saudi Arabia and the Emirates helped consolidate the rule of President Abd al-Fattah as-Sisi following the 2013 military coup.

But a shift appears to have begun to emerge in recent years – most notably in Egypt. Between 2023 and 2025, QIA and, in particular, Abu Dhabi’s ADQ pumped a substantial amount of liquidity into the Egyptian state.50 ADQ’s US$35 billion land lease deal for the Ras al-Hikma coastal area is likely to have averted what at the time was Cairo’s imminent insolvency, as it paved the way for extensive aid from international financial institutions. Many observers deemed ADQ’s intervention to be less a conventional investment than a de facto rescue operation51 – one that may have further increased Egypt’s dependence on the UAE.

In this context, the role of QIA during the 2017–21 Qatar crisis is noteworthy, too. When Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt imposed a blockade on the emirate, Doha was able to draw on the financial resources of its sovereign wealth fund to offset massive capital outflows. QIA transferred at least US$20 billion to the Qatari Ministry of Finance at short notice, thereby helping stabilise the country’s economy.52 Beyond this immediate financial backstop, Hassad Food, a subsidiary of QIA, played a central role in securing domestic food supplies during the initial months of the blockade.53 Moreover, it is widely believed that QIA’s extensive foreign investments contributed to several European countries and, in particular, the United States adopting a stance on the blockade that ranged from sceptical to negative. Qatar’s investments in Turkey, many of which were channelled through QIA, proved especially consequential. In response to the blockade, Ankara expanded its military presence in Qatar, thereby enhancing the emirate’s deterrence capability vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia and the UAE.54 While QIA did not directly augment Qatar’s hard power capabilities, it did significantly strengthen the country’s capacity to withstand the hard power wielded by other states.

In addition to expanding their economic potential, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are using their sovereign wealth funds to develop military capabilities. The lean and centralised decision-making structures of those funds enable both countries to channel capital into armament projects, military infrastructure and security-related industries without having to overcome bureaucratic hurdles.55 Since 2017, PIF has actively promoted the development of an indigenous defence industry through its subsidiary Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI). Within the framework of “Vision 2030”, SAMI is expected to help ensure that more than 50 per cent of Saudi military expenditure remains in the country in future.56 To this end, SAMI has entered into partnerships with a range of foreign defence firms – including the US corporate giants Boeing and Lockheed Martin, the Turkish drone manufacturer Baykar and the Spanish shipbuilding company Navantia – with the aim of developing key military technologies in Saudi Arabia itself.57

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are also using their sovereign wealth funds to develop military capabilities.

In the UAE, Mubadala played a key role in establishing the Emirates Defence Industries Company (EDIC) in 2014; that firm was later integrated into the state-owned defence conglomerate EDGE Group. Although the fund no longer has a stake in EDGE, which now apparently reports directly to the Ministry of Defence, it still holds numerous stakes in companies with close links to the defence sector, including the space technology firm Space4258 and the aviation manufacturer Sanad.59

Soft power

Both the media and academic literature frequently associate sovereign wealth funds with the pursuit of soft power. This association is particularly pronounced in the case of the three Gulf monarchies, which have been seeking to enhance their international standing since at least the early 2000s. Previously, they were widely perceived – especially in Western societies – as politically and socially backward, while their economic success was attributed largely to the export of climate-damaging fossil fuels and the structural exploitation of migrant labour.60 Such perceptions were compounded vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia by the kingdom’s promotion of Salafism around the globe, which won Riyadh followers among the Muslim communities of numerous countries but further damaged its reputation in the West.61 Against this backdrop, all three states set about systematically expanding their soft power capabilities in order to reshape external perceptions and increase their influence in international politics.62 To this end, for the past 20 years or so they have been channelling large investments through their sovereign wealth funds into sectors such as media, sport, education, culture and tourism.

PIF has been particularly active in the media sector. In 2025, it completed the acquisition of a 54 per cent majority stake in MBC Group, the region’s largest media conglomerate, which operates several satellite television channels, including the pan-Arab news channel Al Arabiya.63 The same year, the fund bought a stake in the international sports streaming platform DAZN,64 which holds global broadcasting rights for a wide range of major sporting events. And in late 2025, it was reported that, together with QIA, PIF had provided the financing for Paramount Skydance’s bid for Warner Bros. Discovery, whose assets include CNN.65 Through its shareholdings in the Kingdom Holding Company, PIF also has indirect stakes in various national and international media and social media companies, including X.66

In the sports sector, Qatar’s QIA was the pioneer among the Oil Five. In 2011, its investment subsidiary Qatar Sports Investments (QSI) acquired the French football club Paris Saint-Germain.67 There followed investments in padel tennis (including the takeover of the World Padel Tour) and motorsport (through a stake in Audi’s Formula One team), among others.68 And the sovereign wealth fund also invested in the expansion of Qatar’s sports infrastructure through its subsidiary Qatari Diar ahead of the 2022 World Cup, which was held in Qatar.69 Similarly, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have made sports a key area of investment for their funds. In 2021, after lengthy negotiations, Saudi Arabia’s PIF acquired the British professional football club Newcastle United. In addition, it has been instrumental in the expansion of the Saudi football league – recruiting international stars such as Cristiano Ronaldo, among other measures – ahead of the 2034 FIFA World Cup, which will be hosted by the Kingdom. And it has also invested heavily in international golf, having founded ed LIV Golf as an alternative league to existing professional golf tours and thereby challenging established structures in the sport.70 For its part, the UAE’s Mubadala invested US$10 billion in 2025 in the investment platform TWG Global, which holds stakes in such prominent Western sports franchises as the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Los Angeles Lakers and Chelsea FC.71

Besides sports, the sovereign wealth funds are also involved in the financing of large international conferences. In 2017, for example, PIF founded the Future Investment Initiative Institute. Modelled on the World Economic Forum in Davos, the institute hosts annual conferences at which business leaders and policymakers debate global challenges. At the same time, the format provides a stage for promoting the image of the host country (Saudi Arabia), its development agenda “Vision 2030” and, in particular, its de facto ruler, Mohammed bin Salman.72 In Qatar, QIA has been – at least until 2022 – the main sponsor of the Doha Forum, which has been held in the Qatari capital each year since 2003 as a platform for bringing together policymakers to discuss security issues, in particular.73

In addition, the Oil Five are active in education, culture and entertainment as well as tourism development – sectors in which the Gulf monarchies have been investing heavily through multiple channels over the past two decades. Mubadala was not only responsible for the construction of the main campus of New York University Abu Dhabi in 201074; it continues to maintain a close partnership with the US university. At the same time, it supports Abu Dhabi’s museum landscape through its own foundation.75 QIA is bringing the Art Basel fair to Doha through its subsidiary QSI.76 And PIF has invested in the expansion of Saudi Arabia’s cultural, tourism and leisure infrastructure, not least through the Diriyah urban development project, an official megaproject within the framework of “Vision 2030”. Further, the fund is involved in the entertainment industry – for example, through MDLBEAST, which organises the Soundstorm Festival, one of the largest music events in the Middle East.77 Finally, PIF is engaged in the gaming and e-sports sector. Through its subsidiary Savvy Games Group, it is now considered one of the world’s most influential investors in the video game industry and reportedly exercises influence on game development, including with regard to content.78

There is no doubt that economic interests play a role in the investments outlined above. This is particularly evident in the expansion of national sports infrastructure, which is an integral part of the three countries’ economic diversification strategies. Similarly, investments in the sports sector – for example, in European football clubs – can generate economic opportunities.79 However, the number of extremely costly commitments, such as PIF’s investments in Newcastle United and LIV Golf, cannot be explained by profit motives alone.80 There are other considerations at work here, not least that such investments – especially those in mega sports events – also serve to project the image of the investor country as a dynamic, modern and reliable player on the international stage. The aim of this form of “nation branding” is to shape foreign public opinion and encourage other governments to act in ways that align with the national interests of the investor country.81

But it is by no means certain that such a strategy will always work. In the case of Qatar, the impact of the investments made in hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup has been decidedly ambivalent. On the one hand, those investments paid off only to a limited extent as far as improving the country’s image in the West was concerned. This was because Western media coverage frequently highlighted human rights violations committed by the regime and abuses in the treatment of migrant workers.82 With regard to the Qatar blockade, on the other hand, the tournament may have had a positive effect. For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, it had become increasingly costly to continue the embargo: besides reducing the opportunities for their domestic populations to participate in the event, it was restricting access to potential economic, reputational and tourism-related spillovers associated with the tournament. Thus, the prospect of foregone benefits may have been among the factors encouraging de-escalation and contributing to the conclusion of the Al-Ula Agreement, which formally ended the blockade in 2021.83

Sharp power

In recent years, attempts by the three Gulf monarchies to influence the policies of other states have increasingly come to light. Such practices range from covert influence and espionage to – in isolated cases – the use of political violence beyond national borders to silence critical voices.84 The Oil Five play a role, too, by contributing to the development of the necessary capacities, often in ways that are scarcely apparent to external observers.

Covert political influence is facilitated when the funds conduct business with companies belonging to, or closely associated with, key decision-makers. Such dynamics can be observed in connection with the US administration under President Trump. PIF has links to the Trump family’s business interests through its financing of the LIV Golf Tour: several tournaments have been hosted on golf courses owned by The Trump Organization under commercial leasing and event agreements. Even more significant are the capital commitments to the private equity firm Affinity Partners, which is owned by Jared Kushner, the US president’s son-in-law.85 Affinity received approximately US$2 billion from PIF for asset management, despite reported concerns within the sovereign wealth fund about the firm’s limited experience.86 In 2024, it raised another US$1.5 billion from QIA and the Abu Dhabi–based Lunate, which manages assets on behalf of ADQ. Just how close the business relationship between PIF and Kushner is became evident in September 2025, when it was announced that a consortium led by the Saudi sovereign wealth fund and Kushner’s investment firm had agreed to acquire the US video game manufacturer Electronic Arts for approximately US$55 billion.87 Jared Kushner was also involved in the financing of Paramount’s takeover bid for Warner Bros., which was backed by PIF and QIA.88

Many other examples can be cited. At least until recently, QIA has maintained business ties with Steve Witkoff, a close confidant of Trump who was appointed Washington’s special envoy to the Middle East in 2024.89 For their part, Mubadala and ADIA have invested in funds managed by the billionaire investor Tom Barrack, who currently serves as US ambassador to Turkey. As a result, Barrack has faced accusations of attempting to influence both the election campaign and the administration of his long-time associate Donald Trump as an unregistered “foreign agent” of the UAE.90 Similarly, the close relationship between Mubadala and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair has sparked debates about potential conflicts of interest. According to media reports, Blair was an adviser to the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund in the early 2010s, at a time when he was serving as the special envoy of the Middle East Quartet (comprising the United Nations, the United States, the European Union and Russia).91 The large number of such links point to a strategic pattern in which the Gulf monarchies deploy their sovereign wealth funds in a targeted manner to translate economic relationships – if not outright dependencies – into political influence. Business ties with sitting US decision-makers and former political leaders (such as Blair) who retain extensive international networks offer privileged access to diplomatic processes that include the negotiations over a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip and the broader discussions about the region’s political and economic future.92

Sovereign wealth fund investments could also help the three Gulf countries further expand their technological surveillance and espionage capabilities in future. Over the years, there have been numerous cases of such instruments being deployed. One prominent example is the UAE covert cyberespionage programme known as “Project Raven”, whose operations reportedly involved former US intelligence officials and which targeted human rights activists, journalists and political opponents, including individuals living abroad.93 Another example is the use of the Israeli-developed “Pegasus” spyware by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Moreover, media reports suggest that high-ranking sports officials were subjected to surveillance in the run-up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup as part of what has been dubbed Qatar’s “Project Merciless”.94

At the same time, investments by sovereign wealth funds in relevant surveillance and data-processing technologies have increasingly become public knowledge. Since 2019, Mubadala has held an indirect stake in the Israeli company NSO Group, the developer of the “Pegasus” spyware.95 In 2022, the Saudi Company for Artificial Intelligence (SCAI), another PIF subsidiary, invested more than US$200 million in the Chinese firm SenseTime, which is widely known for its facial recognition and surveillance technologies.96 Two years later, the PIF subsidiary Alat entered into a partnership with one of the largest manufacturers of surveillance technology in China, Dahua Technology, to produce surveillance hardware in Saudi Arabia.97 For its part, QIA acquired a stake in Databricks in 2023,98 a data processing and artificial intelligence company whose platform can also be used for real-time surveillance applications.99

Finally, there are two prominent cases of political violence that can be linked – albeit indirectly – to sovereign wealth funds: the murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018, which was carried out by a hit squad dispatched from the kingdom; and the disappearance of Egyptian-Turkish activist Abdulrahman Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who was arrested in Beirut in late 2024 and shortly thereafter extradited to the UAE.100 Both times, companies in which sovereign wealth funds hold indirect stakes played a role. In the Khashoggi case, according to research carried out by Human Rights Watch, the perpetrators used aircraft belonging to a PIF subsidiary.101 Similarly, when Yusuf al-Qaradawi was flown from Lebanon to Abu Dhabi, the transfer reportedly took place aboard an aircraft operated by an airline in which ADQ – headed by Emirati intelligence chief Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan – holds an indirect stake.102 Although there are no direct connections between the sovereign wealth funds and these two incidents, it is clear that investments by such funds can create corporate structures and logistical infrastructures that, at a minimum, facilitate the sharp power activities of the investor country.

Efforts to Cultivate an Apolitical Image of Sovereign Wealth Funds

The proximity of sovereign wealth funds to the ruling families of the three Gulf monarchies not only creates options for the funds to be deployed as instruments of foreign policy; it also exposes their investments to heightened public and political scrutiny, not to mention resistance in recipient countries. In Spain, for example, an agreement between the Spanish government and ADIA to establish an artificial intelligence research centre sparked sharp criticism from the local scientific community, prompting several members of Spain’s AI advisory board to resign.103 In Germany, media reports pointed to political concerns about the potential takeover by ADQ of Deutsche Bahn’s logistics subsidiary.104 PIF’s investments in sports have proved particularly controversial. Both the acquisition of Newcastle United and the creation of the LIV Golf series have drawn sustained criticism from human rights organisations and fan associations. As was the case for Qatar ahead of the 2022 World Cup, the three Gulf monarchies are frequently accused of “sportswashing”, that is, attempting to enhance their international image and divert attention from domestic human rights abuses through high-profile involvement in global sports.105 In the United States, such activities have led to scrutiny by oversight bodies, including the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. And following the terrorist attack against Israel on 7 October 2023, the NGO Counter Extremism Project – which regularly cooperates with Western governments – went even further, calling for a global freeze on assets held by QIA in order to put pressure on Qatar to arrest Hamas leaders living in exile in that country.106

What is more, certain foreign investments by sovereign wealth funds could trigger a significant domestic backlash within the Gulf monarchies themselves. This applies, in particular, to investments in the Israeli market, which are generally a highly sensitive issue in domestic politics. While they are attractive to governments not only for economic reasons but also because of the access they provide to advanced technologies – especially in the fields of surveillance and security – they remain controversial among the wider population. Opinion polls in Saudi Arabia and the UAE indicate that even before the war in Gaza between Israel and Hamas, a majority of respondents were opposed to economic relations with Israel – often by a significant margin.107

|

Info box |

||

|

The largest single investment by an Arab sovereign wealth fund in Israel to date was Mubadala’s entry into the Tamar and Dalit offshore gas fields. In 2021, the Emirati fund acquired a 22 per cent stake in the Israeli offshore reserves for approximately US$1 billion; it continues to hold an 11 per cent share today.a All five sovereign wealth funds of the Gulf monarchies maintain a presence in the Israeli market, primarily through indirect channels. Their exposure is mediated largely via holdings in private equity and venture capital firms and thus remains mostly below the threshold of public reporting. Consequently, only a limited number of investments are public knowledge. As part of the Abraham Accords, signed in 2020, the United Arab Emirates announced a new US$10 billion investment fund for projects in Israel.b By 2022, Mubadala had invested roughly US$100 million in the Israeli technology sector.c The sovereign wealth funds of Saudi Arabia and Qatar are represented in Israel mainly through capital allocations to US-based investment firms. Of particular note is Affinity Partners, the investment firm founded by Jared Kushner, which is capitalised primarily by the Public Investment Fund and the Qatar Investment Authority, along with the indirect involvement of ADQ. Affinity Partners has since invested several hundred million US dollars in the Israeli financial sector.d Also noteworthy is Liberty Strategic Capital, established by former US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin with the explicit aim of channelling Gulf and US capital into the Israeli high-tech sector.e To date, Liberty Strategic Capital has publicly disclosed investments of approximately US$850 million in two Israeli cybersecurity companies. The sovereign wealth funds of the three Gulf monarchies appear to account for the bulk of that sum. Additional capital from those funds may reach the Israeli market indirectly through large, globally active private equity firms, such as Blackstone and Carlyle. However, both the initial capital commitments by sovereign wealth funds and the resulting downstream investments can be traced to only to a limited extent. Meanwhile, technology companies, in particular, are becoming increasingly internationalised. The cybersecurity firm Snyk, originally founded in Israel by former members of Unit 8200 (the Israeli military’s cyber and intelligence unit), has since established its headquarters in the United States. In December 2022, the Qatar Investment Authority led a financing round for the company, contributing approximately US$196.5 million.f |

So far, the Gaza war has had no discernible impact on the investment behaviour of the Gulf sovereign wealth funds towards Israel. By contrast, in light of the developments in Gaza and the West Bank, Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) has terminated contracts with asset managers overseeing its Israeli investments and divested parts of its portfolio in the country.g There is no evidence of any comparable reassessment or divestment by the sovereign wealth funds of the Gulf monarchies. a Shangyou Nie and Robin Mills, Eastern Mediterranean Deepwater Gas to Europe: Not Too Little, But Perhaps Too Late (New York, N.Y.: Center on Global Energy Policy [CGEP], 21 March 2023), https:// www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/eastern-mediter ranean-deepwater-gas-to-europe-not-too-little-but-perhaps-too-late/ (accessed 18 August 2025). b UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “UAE Announces £7 billion Fund for Investments in Israel”, 15 March 2021, https://www. mofa.gov.ae/en/missions/tel-aviv/media-hub/embassy-news/uae-announces-£7-billion-fund-for-investments-in-israel (accessed 18 August 2025). c Rory Jones and Dov Lieber, “U.A.E. Just Invested $100 Million in Israel’s Tech Sector as Both Countries Get Closer”, The Wall Street Journal (online), 14 January 2022, https://www.wsj. com/world/middle-east/u-a-e-sovereign-wealth-fund-invests-100-million-in-israel-venture-capital-firms-11642164356 (accessed 18 August 2025). d Dan Williams and Galit Altstein, “Kushner’s Affinity Gets Nod to Double Stake in Israel’s Phoenix”, Bloomberg (online), 15 January 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/ 2025-01-15/trump-son-in-law-kushner-s-affinity-gets-nod-to-double-stake-in-israeli-firm (accessed 28 January 2026). e Sophie Shulman, “Steve Mnuchin: ‘We’re Looking at Some Very Large Significant Investment Opportunities in Israel’”, ctech (online), 15 January 2024, https://www.calcalistech.com/ ctechnews/article/hybqhtbkp?utm (accessed 18 August 2025). f Abigail K. Leichman, “Qatar Fund Leads Investment in Israeli-US Cyber Unicorn”, ISRAEL21c (online), 18 December 2022, https://israel21c.org/qatar-fund-leads-investment-in-israeli-us-cyber-unicorn/?utm (accessed 18 August 2025). g “Norway Wealth Fund Terminates Israel Asset Management Contracts”, Reuters (online), 11 August 2025, https://www. reuters.com/sustainability/society-equity/norway-wealth-fund-terminates-israel-asset-management-contracts-2025-08-11/ (accessed 18 August 2025). However, the Norwegian parliament voted in November 2025 to suspend further “ethical divestments” for the time being in order to review the underlying guidelines. Fouche, “Norway Pauses Wealth Fund’s Ethical Divestments” (see note 33). |

|

It is likely that the mood in Qatar was similar at that time. And in the aftermath of the war, the negative attitudes in all three countries can be expected to have further intensified, especially following the Israeli strike targeting senior Hamas leaders in Doha in September 2025.108

Against this background, the three Gulf monarchies seek to present their sovereign wealth funds as apolitical actors that operate independently of the ruling families. However, such efforts are by no means always successful. In the context of the takeover of the British football club Newcastle United, for example, PIF asserted that the Saudi state would exercise no control over the club109 – a somewhat unconvincing assertion given the close personal ties between the fund and the royal family. Such declarations are further undermined by the fund explicitly emphasising its state character. During a legal dispute in the US between the LIV Golf League, which is financed by PIF, and the PGA Tour, PIF Governor Yasir Al-Rumayyan sought to quash a subpoena by arguing that the fund should be treated as an instrument of the Saudi state and consequently entitled to sovereign immunity. Had that argument been accepted, it would have shielded both the fund and its governor in his official capacity.110 In the case of Mubadala, the line between state and private equity capital is blurred through its subsidiary Mubadala Capital. That entity not only manages a portion of the sovereign wealth fund’s own assets but also oversees capital from external investors (third-party capital).111 While there may be economic reasons for this, it serves only to reinforce the perception of Mubadala Capital as a commercially oriented and politically neutral investment firm – its close institutional ties to the Emirati state notwithstanding.

At the same time, all five sovereign wealth funds are increasingly investing in internationally active private equity firms. As a result, the presence of these firms, which compete for investment capital from the sovereign wealth funds, has increased significantly in the Gulf region in recent years.112 From an economic perspective, this development is advantageous for the sovereign wealth funds in several ways. First, it allows them to channel private equity investments into their home countries. Second, it contributes to the further professionalisation of their own investment management. And third, it creates opportunities to invest in politically sensitive sectors – such as the Israeli high-tech industry – at least partly beyond the scrutiny of the domestic public (see Table, p. 30f.).

Outlook and Conclusions

While it may be difficult to prove empirically that individual investments by the sovereign wealth funds of the Gulf monarchies are directly motivated by foreign policy considerations, the above analysis shows that, through their global and domestic activities, the Oil Five are making a significant contribution to expanding the foreign-policy room for manoeuvre of those countries and their political leaderships. The funds play a central role in building hard, soft and sharp power capabilities. At the same time, there are differences between the three countries not only with regard to their strategic priorities but also in the importance of their sovereign wealth funds for foreign and security policy. In Saudi Arabia, PIF functions as the central steering instrument of “Vision 2030” and underpins almost every investment that enhances the kingdom’s international standing. By contrast, in Qatar and the UAE, sovereign wealth funds are just one of several foreign policy levers. Qatar’s soft power potential is closely tied to the Al Jazeera media network, which operates independently of QIA. And in the UAE, responsibility for the expansion of the defence industry has shifted away from Mubadala to the Ministry of Defence. At the same time, family offices are becoming increasingly important in the Emirates.

However, it can be assumed that, overall, the sovereign wealth funds will continue to play a central role in the foreign policy of the three Gulf states not least because of their sustained growth. That growth is being driven not only by returns from global investments but also by direct capital injections from the state, as is particularly evident in the case of PIF. In 2024, the Saudi fund was forced to write down the value of several oversized domestic infrastructure projects;113 but at the same time, its assets under management increased by 19 per cent compared with the previous year, as it received additional shares in the state-owned oil company Aramco.114 Moreover, PIF, ADQ and Mubadala are increasingly raising third-party capital in the form of bond issuance in order to expand their funding options.115

Understandably, Germany and its European partners have an interest in attracting the sovereign wealth funds of the Gulf monarchies as investors. The Oil Five have considerable amounts of capital at their disposal and, in most cases, pursue a long-term investment horizon. This creates opportunities to finance large infrastructure projects, boost the financial resilience of companies in strategically important sectors and facilitate improved access to markets in the Gulf region. Nevertheless, it is essential that a more critical assessment of these funds be undertaken – and not solely from an economic perspective. The growing foreign policy relevance of the Oil five for the Gulf states presents two key challenges for Europe.

First, with regard to individual investments by sovereign wealth funds, undesirable side effects must be identified and addressed at an early stage. In particular, safeguards are needed to prevent critical infrastructure from coming under the control of sovereign wealth funds or sensitive military and security technologies being transferred to the Gulf monarchies, where they could contribute to strengthening the state’s capacities for repression or be indirectly passed on to third countries – not least China. Such scrutiny will require not only greater awareness of the issue on the part of European policymakers but also robust and effective investment screening mechanisms. In this respect, EU countries appear to be lagging the United States, which has recently expanded the powers and sanctioning capabilities of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and significantly increased the body’s staffing levels.116 Moreover, the US administration has explicitly focused – at least until now – on the sovereign wealth funds of the Gulf monarchies, whose close ties with China were viewed with extreme scepticism under President Joe Biden.117

The question of whether the EU and its member states have adequate control mechanisms in place is particularly important because sovereign wealth funds invest not only directly but also indirectly – namely, through stakes in private equity and venture capital firms, which, in principle, grant them access to sensitive corporate information.118 In 2023, the European Court of Auditors welcomed the introduction of an EU-wide framework for the screening of foreign direct investment but at the same time expressed significant doubts about its efficiency and effectiveness. Those concerns stem not least from the fact that in this area, Member States continue to apply procedures, levels of scrutiny, and administrative resources that diverge widely.119 Even in Germany, which has one of the most stringent investment-screening architectures in Europe, there is still room for improvement when compared with the US system – for example, with regard to the strategic integration of the screening regime and the systematic use of intelligence-based information.120

Second, and more important, Germany and its European partners must fundamentally address the much more active foreign policy of the Gulf monarchies that is being facilitated by the investments of their sovereign wealth funds. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar increasingly perceive themselves as regional powers and, since the “Arab Spring”, have repeatedly sought to influence developments and steer crises – both in their immediate neighbourhood and beyond – in accordance with their own interests.121 And as the international order becomes increasingly multipolar, their significance for Germany and its European partners only grows. Today, the Gulf monarchies are gaining weight not only as energy suppliers and providers of capital but also as geopolitical shapers; however, from a European perspective, they are by no means always constructive actors.

Although the Gulf monarchies played an important role as mediators and supporters of ceasefire initiatives in the recent Gaza war, there have been other cases in which they have promoted instability. Above all, the militarisation of their foreign policy – through extensive military aid and, at times, even direct intervention – has fuelled regional and domestic conflicts.122 This can be seen from their varying degrees of involvement in the civil wars in Yemen, Libya, Sudan and Syria, whereby the UAE stands out for its interventionist approach.123 For Europe, there have been – and continue to be – directly tangible consequences, not least in the form of increasing refugee and migration flows. Moreover, the three monarchies are not acting consistently in the interests of Germany or Europe at either the regional or international level. From a European perspective, their deepening rapprochement with China, which now extends well beyond economic cooperation, is as problematic as their demonstratively cooperative stance towards Russia.124 Finally, in international climate negotiations, the three Gulf states regularly seek to dilute the more ambitious European decarbonisation initiatives, despite their own significant investments in renewable energy.125

Against this backdrop, it is evident that engaging with the Oil Five and their owners requires far more than just effective investment screening. While the Gulf monarchies are increasingly interlocking their economic and foreign policy interests and deliberately expanding their room for manoeuvre through the strategic use of sovereign wealth funds, Europe has so far lacked a coherent approach – one that effectively integrates economic and foreign policy objectives. In particular, Germany’s approach to date has proved of limited effectiveness. It has made very public demands on issues such as human rights; but at the same time, it has actively courted both the sovereign wealth funds and the companies they control as investors and business partners.126

Another approach is urgently needed. The Europeans should clearly define their shared core interests and pursue them through a consistent policy towards the Gulf monarchies and their sovereign wealth funds, which do not act as a unified actor vis-à-vis Europe. By doing so, they could capitalise on existing divisions among the Gulf states. The blockade of Qatar and, more recently, the pronounced tensions127 between Saudi Arabia and the UAE demonstrate that these countries have significantly divergent interests and, at times, compete with one another openly and aggressively. Germany and its European partners should exploit this situation by identifying how such frictions can be leveraged to advance their own strategic interests, especially in relation to the sovereign wealth funds.

Above all, Germany and its European partners should also take advantage of the fact that while the Oil Five provide important investment capital, they are dependent on stable markets – for both their existing commitments and future investments. Not least because of the growing uncertainties in the United States under President Trump, markets other than the US are becoming more important for the sovereign wealth funds. In recent years, all five have intensified their activities in Asia, in particular.128 At the same time, Europe, with its relatively high level of political stability, reliable legal framework and economically resilient single market, has also gained in importance for their investment portfolios.129 Various developments in recent years illustrate this trend. In 2018, Mubadala announced plans to establish a US$400 million technology fund aimed at investing in European companies in a targeted manner; and in September 2025, it acquired two leading European asset managers through one of its subsidiaries.130 Having announced in 2024 that it was going to strengthen its focus on domestic investments,131 PIF proceeded to open its own office in Paris the very next year and declare its intention to double its investments in Europe.132 QIA, for its part, announced plans to expand its investments in smaller European companies with high growth potential.133 And German companies are likely to be among those that remain on the radar of the sovereign wealth funds in future. That applies not only to QIA, which so far has been the most active investor in Germany, but also to the other four funds, whose investments in the country have been gradually increasing in recent years (see Table, p. 30f.). European governments should leverage the funds’ growing interest in the continent as an investment destination to strengthen their own negotiating position vis-à-vis the three Gulf monarchies and to promote greater alignment with European interests.

Abbreviations

|

ADIA |

Abu Dhabi Investment Authority |

|

BoD |

Board of directors |

|

CEDA |

Council of Economic and Development Affairs |

|

EDIC |

Emirates Defence Industries Company |

|

GPFG |

Government Pension Fund Global |

|

IMF |

International Monetary Fund |

|

IPIC |

International Petroleum Investment Company |

|

IPO |

Initial public offering |

|

KIA |

Kuwait Investment Authority |

|

MEED |

Middle East Economic Digest |

|

NGO |

Non-governmental organisation |

|

PIF |

Public Investment Fund |

|

QIA |

Qatar Investment Authority |

|

QSI |

Qatar Sports Investments |

|

RSF |

Rapid Support Forces |

|

SAMA |

Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority |

|

SAMI |

Saudi Arabian Military Industries |

|

SCISP |

Saudi Centre for International Strategic Partnerships |

|

SWF |

Sovereign wealth fund |

|

UAE |

United Arab Emirates |

Appendix:

Table

|

Fund |

Target company (location) |

Investment |

Status |

Sector(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ADQ (UAE) |

Noatum Autologistics Germany (Schutterwald) |

Indirect (via AD Ports Group, |

Ongoing |

Logistics |

|

ADQ (UAE) |

Porsche AG (Stuttgart) |

€350mn, cornerstone investor in IPO |

Unclear |

Automotive |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Porsche AG (Stuttgart) |

Cornerstone Investor in the IPO, |

Unclear |

Automotive |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Volkswagen AG (Wolfsburg) |

10.4 % capital, ~17 % voting rights (via Qatar Holding, subsidiary of QIA) |

Ongoing |

Automotive |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Hapag-Lloyd AG (Hamburg) |

12.3 % (via Qatar Holding, subsidiary of QIA) |

Ongoing |

Shipping / logistics |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

RWE AG (Essen) |

~9.1 % (after €2.5bn mandatory convertible bond) |

Ongoing |

Energy / renewables |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Deutsche Bank AG (Frankfurt) |

6.1 % (direct) |

Ongoing |

Finance |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Siemens AG (Munich) |

~3 % (direct) |

Ongoing |

Industry / technology |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Celonis (Munich) |

~€400mn investment |

Ongoing |

Software / process mining |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Porsche AG (Stuttgart) |

4.99 % of preferred shares, |

Ongoing |

Automotive |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Siemens Healthineers (Forchheim) |

€380mn investment |

Ongoing |

Medical technology |

|

QIA (Qatar) |

Hochtief AG (Essen) |

~10 % (direct) |

Exited 2015 |

Construction |

Endnotes

- 1

-

Although there is no universally accepted definition, a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) is generally described as an investment vehicle controlled by a national or regional government that invests government surpluses in securities and other assets in order to generate economic returns. Unlike central banks, which manage currency reserves primarily to stabilise monetary and exchange-rate policy, sovereign wealth funds have a return-oriented investment objective. They also differ from pension funds, whose purpose is to secure future pension payments for specific groups making contributions.

- 2

-

Dayan A. Tine, “Saudi PIF on Track to Reach $2tn in AuM, 2nd-Largest Globally by 2030”, Arab News (online), 10 January 2025, https://www.arabnews.com/node/ 2585907/business-economy (accessed 20 October 2025).

- 3

-

Holger Hansen and Maria Martinez, “Germany’s 2025 Borrowing Undershoots Plan as Spending Falls, Revenues Rise”, Reuters (online), 23 January 2026, https://www. reuters.com/business/germanys-2025-borrowing-undershoots-plan-spending-falls-revenues-rise-2026-01-23/ (accessed 24 January 2026).

- 4

-

Hannes Baumann, “Monetary Statecraft in the Service of Counter-Revolution: Gulf Monarchies’ Deposits to Arab States’ Central Banks 1998–2022”, Review of International Political Economy 32, no. 4 (2025), 1122–44 (1126).

- 5

-

Tokhir N. Mirzoev et al., The Future of Oil and Fiscal Sustainability in the GCC Region (Washington, D.C.; International Monetary Fund, 2020), 17, https://www.imf.org/en/ Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2020/ 01/31/The-Future-of-Oil-and-Fiscal-Sustainability-in-the-GCC-Region-48934 (accessed 28 August 2025).

- 12

-

Karen Kwok, “Breakingviews – Saudi Fund’s Prudence Pivot Is Only Half Complete”, Reuters (online), 20 August 2024, https://www.reuters.com/breakingviews/saudi-funds-prudence-pivot-is-only-half-complete-2024-08-20/?utm (accessed 20 August 2025).

- 13

-

Cláudio Afonso, “Lucid-Uber: How Saudi Arabia’s PIF Is Bringing Together Its Two Investments”, EV (online), 20 July 2025, https://eletric-vehicles.com/lucid/lucid-uber-how-saudi-arabias-pif-is-bringing-together-its-two-investments/?utm (accessed 28 August 2025).

- 14

-

For Abu Dhabi’s “Vision 2030”, see United Arab Emirates’ Government Portal, “Abu Dhabi Economic Vision 2030”, https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/finance-and-economy/ abu-dhabi-economic-vision-2030 (accessed 29 August 2025); for Qatar’s, see State of Qatar, Government Communications Office, “Qatar National Vision 2030” (online), https://www. gco.gov.qa/en/state-of-qatar/qatar-national-vision-2030/our-story/ (accessed 29 August 2025); and for Saudi Arabia’s, see Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, “Saudi Vision 2030”, https://www. vision2030.gov.sa/en (accessed 29 August 2025).

- 15

-

John Calabrese, “The New Wave of Dealmaking by Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds”, Middle East Institute, 20 July 2023, https://www.mei.edu/publications/new-wave-deal making-gulf-sovereign-wealth-funds (accessed 26 May 2025).

- 16

-

See, for example, Alexis Montambault-Trudelle, “Money Trees in the Gulf: The Power of Sovereign Wealth Funds in Shifting GCC International Politics”, Orient 64, no. 2 (2023).

- 17

-

Diana Galeeva, “The Benefits of Chequebook Diplomacy”, Arab News (online), 4 May 2025, https://www.arabnews.com/ node/2599523 (accessed 26 May 2025).

- 18

-

Hadeel Al Sayegh and Yousef Saba, “Abu Dhabi Fund ADQ Wields Economic Diplomacy to Forge Regional Ties”, Reuters (online), 16 October 2022, https://www.reuters.com/ world/middle-east/abu-dhabi-fund-adq-wields-economic-diplomacy-forge-regional-ties-2022-10-16/ (accessed 28 January 2025).

- 19

-

“Abu Dhabi’s Investment Guidelines”, The Wall Street Journal (online), 17 March 2008, https://www.wsj.com/ articles/SB120578495444542861 (accessed 22 August 2025).

- 20

-

In the case of ADIA, Mubadala and QIA, the standards have been implemented in accordance with the respective Santiago Principles Self-Assessments; see International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, “Santiago Principle Self-Assessments”, https://ifswf.org/assessments (accessed 29 September 2025). The PIF reports that it has also adopted the Generally Accepted Principles and Practices of the Santiago Principles; see PIF, “Our Governance and Investment Decisions”, https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/our-investments/ governance-and-investment-decisions/ (accessed 29 September 2025). Only ADQ has so far made no explicit reference to the Santiago Principles.

- 21

-

Abu Dhabi Media Office, “In His Capacity as Ruler of Abu Dhabi Khalifa Bin Zayed Issues a Law to Establish the Supreme Council for Financial and Economic Affairs”, press release, 27 December 2020, https://www.mediaoffice. abudhabi/en/government-affairs/Khalifa-bin-Zayed-issues-law-establish-Supreme-Council-Financial-Economic-Affairs/ (accessed 5 August 2025). For Qatar, see Qatar Investment Authority, “Governance”, https://www.qia.qa/en/About/ Pages/Governance.aspx (accessed 29 September 2025).

- 22

-

Montambault-Trudelle, “Money Trees in the Gulf” (see note 16), 31.

- 23

-

“Al-Rumayyan Affirms the Significance of the Saudi-Chinese Summits and Investment Opportunities”, Saudi Press Agency, 8 December 2022, https://www.spa.gov.sa/w1824025 (accessed 20 August 2024).

- 24

-

Saudi Centre for International Strategic Partnerships (SCISP), “Mission, Vision, Values”, https://scisp.gov.sa/web/ about-us/mission-vision-values?csrt=1128497720371898836 (accessed 20 August 2024).

- 25

-

SCISP, “Board of Directors”, https://scisp.gov.sa/web/ about-us/board-of-directors?csrt=2702209398069337378 (accessed 20 August 2024).

- 26

-

Yousef Saba, “Abu Dhabi Shakes up Wealth Funds with Top Royals Chairing”, Reuters (online), 9 March 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/abu-dhabi-shakes-up-wealth-funds-with-top-royals-chairing-2023-03-09/ (accessed 14 May 2025).

- 27

-

Steinberg, Regional Power United Arab Emirates (see note 6), 8.

- 28

-

Johannes Späth et al., Survival Strategies in the Middle East: Foreign Policy in the Service of Regime Security, Policy Analysis, no. 1 (Vienna: Austrian Institute for International Affairs, January 2024), https://www.oiip.ac.at/cms/media/policy-analysis-survival-strategies-in-the-middle-east.pdf (accessed 15 May 2025).

- 29

-

United Arab Emirates, Executive Affairs Authority, “Chairman of the Executive Affairs Authority – H. E. Khaldoon Khalifa Al Mubarak”, https://eaa.gov.ae/en/pages/chairman-executive-affairs-authority.html (accessed 12 July 2024).

- 30

-

See Guido Steinberg, Qatar’s Foreign Policy: Decision-Making Processes, Baselines and Strategies, SWP Research Paper 4/2023 (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, April 2023), 7ff., doi: 10.18449/2023RP04.

- 31

-

As his brother’s secretary for investment affairs, Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani is largely responsible for the emir’s investment strategy. See Qatar Investment Authority, “Leadership”, https://www.qia.qa/en/ About/Pages/leadership.aspx (accessed 4 September 2025).

- 32

-

For an overview, see Alvaro Cuervo-Cazurra et al., “A Review of the Internationalisation of State-Owned Firms and Sovereign Wealth Funds. Governments Nonbusiness Objectives and Discreet Power”, Journal of International Business Studies (2022), 1, doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4030118.

- 33

-

Ibid., 30. The fund is currently planning to revise its guidelines, which is why the implementation of “ethical divestments” has been temporarily suspended. See Gwladys Fouche, “Norway Pauses Wealth Fund’s Ethical Divestments”, Reuters (online), 4 November 2025, https://www. reuters.com/business/finance/norway-poised-pause-wealth-funds-ethical-divestments-2025-11-04/ (accessed 14 November 2025).

- 34

-

Daniel W. Drezner, “Sovereign Wealth Funds and the (In)Security of Global Finance”, Journal of International Affairs 62, no. 1 (2008), 115–30 (119).

- 35

-

Kyle J. Hatton and Katharina Pistor, Maximising Autonomy in the Shadow of Great Powers: The Political Economy of Sovereign Wealth Funds, Columbia Law and Economics Working Paper no. 395 (17 March 2011), doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1787565.

- 36

-

For an overview of the state of research, see Tomasz Kaminski, “Political Significance of Sovereign Wealth Funds”, in Political Players? Sovereign Wealth Funds’ Investments in Central and Eastern Europe, ed. Tomasz Kaminski (Łódź: Łódź University Press, 2017), 25–43.

- 37

-

See, e.g., Rolando Avendaño and Javier Santiso, Are Sovereign Wealth Funds’ Investments Politically Biased? A Comparison with Mutual Funds, Working Paper no. 283 (Paris: OECD Development Centre, December 2009), https://www.oecd.org/ content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2010/01/are-sovereign-wealth-funds-investments-politically-biased_ g17a1d71/218475437211.pdf (accessed 27 October 2025).

- 38

-