Facets of the North Korea Conflict

Actors, Problems and Europe’s Interests

SWP Research Paper 2018/RP 12, 14.12.2018, 85 Seiten ForschungsgebieteEven after the summit meeting between US President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Head of State Kim Jong Un in Singapore on 12 June 2018, the crisis surrounding North Korea’s nuclear programme and weapons of mass destruction programme remains one of the most dangerous and complex in the world. The conflict is centred on the unresolved tense relationship between North Korea and the USA, and in particular the issue of nuclear weapons possession. Grouped around this are other conflicts characterised by clashes of interests between China, Japan, North Korea, Russia, South Korea and the USA. In addition, within these conflicts, security policy, human rights policy and economic policy have great impact on each other.

For Germany and Europe, finding a peaceful solution to the conflict – or at least preventing military escalation – is key. Europe can and should work to ensure that North Korea is treated as a challenge to global governance. Addressing the set of problems subsumed under the term “North Korea conflict” in such a way as to avoid war, consolidate global order structures, and improve the situation of the people in North Korea requires staying power and can only lead to success one step at a time.

Table of contents

Facets of the North Korea Conflict

2 Interests, Interdependencies and a Gordian Knot

2.2 The North Korean Problem: A Brief History

3 North Korea: Between Autonomy-Seeking and the Pursuit of Influence

3.1 North Korea’s Changing Patterns of Legitimisation

3.1.1 Change of Discourse during the Iraq War 2003

3.1.2 North Korea’s Nuclear Breakthrough

3.1.3 The Institutionalisation of Nuclear Power Status

3.2 North Korea’s Nuclear Ambitions: between Domestic and Foreign Policy Motives

3.2.1 The Nuclear Programme as a Security Project

3.2.2 The Nuclear Programme as an Identity Project

3.2.3 The Nuclear Programme as a Historical Project

3.2.4 The Nuclear Programme as a Bargaining Chip

3.3 North Korea’s Nuclear Foreign Policy: Between Striving for Autonomy and Maximising Influence

4 South Korea: Caught in the Middle or Mediating from the Middle?

4.1 Diverse Threats from the North

4.3 Options for Exerting Influence

4.5 The Struggle for a Voice and Co‑Determination

5.1 From “Strategic Patience” to “Massive Pressure”

5.2 Diplomatic and Political Contradictions of US Policy

5.3 The Debate on Military Options

6 China: Between Key Role and Marginalisation

6.2 Goals and Strategies of China’s Policy on the Korean Peninsula

6.3 China’s North Korea Policy in Transition

7 Russia: A Possible Mediator?

7.1 Russia’s Threat Perception

7.3 Russia as Mediator? Arguments for ...

7.5 Opportunities for Cooperation with Russia: Limited and Untapped

8.1 Relationships Burdened by History

8.3 Goals, Strategies, Options

9 Non-Proliferation: Containing a Rule Breaker

9.1 North Korea and the Non‑Proliferation Regime

9.2 North Korea and Nuclear Proliferation

9.3 What Germany and the EU Can Do

10 Human Rights Policy: No Trade‑Off Necessary

10.1 North Korea’s Crimes against Humanity

10.2 The Response of the International Community

10.3 North Korea’s Human Rights Strategy

11 Diplomacy: Going Round and Round in Circles?

11.2.2 Multilateral Negotiations

11.4 Prospects and the Role of Germany or the EU

12 Sanctions: Their Development, Significance and Results

12.1 Sanctions against North Korea

12.1.1 Unilateral Sanctions by the US

12.1.2 Collective Sanctions by the UN Security Council

12.1.3 Unilateral Sanctions by the EU

12.2 Sanctions: Objectives and Results

12.2.1 The Objectives of the Sanctions Policy

12.3 North Korean Counter-Measures

12.4 The Sanctions Policy against North Korea: Significance and Problems

13 Military Options: (Too) Much Risk for (Too) Little Promise

13.1 Expanding Deterrence and Defence

13.2 Military Pre-emptive Intervention

14 Cyberspace: Asymmetric Warfare and Cyber-Heists

14.1 North Korea’s Strategic Use of Cyberspace

14.2 Structure and Organisation

14.3 Overview of North Korean Cyber Operations

15.1 Historical Legacies and Path Dependencies

15.2 Interdependencies between the Various Sets of Problems

15.4 Germany and Europe: Only Onlookers?

15.5 Risks and Consequences for Europe

15.5.1 Military and Defence Policy Implications

15.5.2 Economic Consequences of a Korean War

15.5.3 The Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction

15.5.4 Erosion of the Non-Proliferation Treaty

15.5.5 Implications for the Transatlantic Relationship

15.5.6 Human Rights Violations in North Korea

15.6 Europe’s Relations with the DPRK

15.7 European Instruments and Elements of Action

Online dossier to the Research Paper

http://bit.ly/SWP18DNK_Introduction

Map 1 North and South Korea in the regional environment

Issues and Recommendations

Facets of the North Korea Conflict: Actors, Problems and Europe’s Interests

The conflict over North Korea’s nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction programmes remains one of the most dangerous and complex crises in the world, even after the summit between US President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Head of State Kim Jong Un in Singapore on 12 June 2018. The risk of military escalation is enormous. Given the involvement of four nuclear weapon possessors, the use of nuclear weapons cannot be ruled out. But the conflict remains explosive even below the threshold of open violence. North Korea has openly and directly challenged the international community by ignoring UN Security Council decisions and other global norms and rules. The proliferation of weapons and weapons technology threatens to fuel instabilities in other parts of the world. The credibility of the nuclear non-proliferation regime is in question. Asymmetric strategies, such as North Korean cyber attacks and cyber raids, pose new challenges for the international community.

The Trump administration is striving for a sustainable conflict resolution based on an agreement at the highest political level between Pyongyang and Washington. Such a dialogue is an important, but not sufficient prerequisite for a sustainable solution. The North Korea conflict is the focal point of a mix of various, confounding problem constellations. To unravel them will require a step-by-step approach that takes into account the diverging interests of the actors involved and their historical sensitivities.

The conflict focuses on the unresolved question of the relationship between North Korea and the USA, and is centred on the issue of nuclear weapons possession. Pyongyang sees its nuclear deterrent against the United States as a guarantee of its security. Washington, on the other hand, is not prepared to accept mutual vulnerability and has threatened military escalation.

However, further conflicts are grouped around this antagonism, which are characterised by clashes of interests between China, Japan, North Korea, Russia, South Korea and the USA. Neighbouring states are following the conflict between Pyongyang and Washington with concern, not only because of the immediate effects of any war, but also with regard to their own foreign and security policy interests. China’s great power ambitions are challenged by a nuclearised North Korea and would suffer a setback through a military escalation that ended in reunification under South Korean-American auspices. South Korea, which is particularly exposed and seeks reconciliation and détente with the North, has been trying to promote dialogue between the USA and North Korea without damaging its relations with other parties. While Russia has a direct presence in East Asia, it views its policy on the North Korea conflict more as a variable that is dependent on its relations with the USA. Moscow would probably only aspire to a mediating role under certain circumstances.

North Korea’s totalitarian rule, its catastrophic human rights situation and its opacity are further obstacles to integrating the country into international contexts in a way that promotes peace.

Historical legacies also make conflict resolution more difficult. Tainted by colonial times, the Korean War and the Cold War continue to influence perceptions today and restrict important actors’ room for manoeuvre. For example, Japan’s historically charged role in Korea, the unresolved question of Japanese citizens abducted by North Korea, and its dependence on the United States for security policy all put Tokyo in a precarious position.

In addition, there are numerous interferences between the various conflicts. Such interactions, for instance between security, human rights and economic policies, may be deliberate (e.g. when an easing of sanctions is offered as an incentive for disarmament efforts) or unintended (e.g. when security guarantees vis-à-vis North Korea weaken US alliances with allies).

For Germany and Europe, finding a peaceful solution to the conflict – or at least avoiding military escalation – is key. The consequences of a war in Korea would be felt in Europe. In addition to the economic implications of a military conflict in one of the world’s economically most important regions, such a conflict would also be a tremendous shock to the global security architecture. East Asia could become a permanent crisis region. Europe’s alliance with the USA would be affected, for example, if the NATO collective defence clause was activated.

Europe and Germany are not actors in East Asia that could have a direct impact on the conflict. However, Europe has opportunities to exert indirect influence on the powers involved in the conflict. It can contribute European experience in conflict management, and provide positive incentives through political, economic and humanitarian offers. It should warn the USA against military responses and urge China to implement the sanctions adopted by the UN Security Council.

Europe can use its economic and political influence to urge third countries to strictly implement the sanctions regime. Europe can and should work to ensure that North Korea is treated as a challenge to the global order. Partial and interim solutions with Pyongyang may be necessary to defuse the conflict. However, such solutions must not violate the norms and rules agreed in multilateral regimes. A de facto recognition of North Korea’s nuclear weapons possession, for instance, may be a prerequisite for agreeing on a disarmament process. A formal upgrading of North Korea to a nuclear weapons state would, however, permanently affect the non-proliferation regime. In human rights policy, Europe also needs to maintain visible and lasting pressure on North Korea, while at the same time keeping the issue strictly separate from security policy.

There is a great deal to suggest that addressing the set of the problems subsumed under the term “North Korea conflict” in a way that avoids war, consolidates global governance structures and improves the situation of the people in North Korea, requires staying power and will only lead to success one step at a time. The political dialogue with North Korea that was launched by the Trump administration in Singapore can promote such a process. It is unlikely to be enough.

Hanns Günther Hilpert and Oliver Meier

Interests, Interdependencies and a Gordian Knot

In Singapore on 12 June 2018, the heads of state and government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the United States of America met for the first time. Assessments of the outcome of this historic summit between Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump could hardly be more different. While the US President spoke of a breakthrough and tweeted on his way home that North Korea no longer presented a nuclear threat,1 others consider the summit’s sparse final declaration2 to be lacking in substance and perspective. They deplore the fact that North Korea received a substantial political upgrade without having to offer any meaningful concessions in return; they point out that Pyongyang has not promised any concrete steps towards disarmament; and they are unsure how any future political process to agree such steps might unfold.3

For now, the only remaining hope is that the unprecedented attempt to defuse – or even permanently resolve – a conflict that has lasted for more than half a century by initiating talks at the highest level will be successful. Such a breakthrough would be equivalent to the proverbial cutting of the Gordian knot: the problem commonly referred to as “the North Korea conflict” is actually a whole complex of diverse interwoven problems. The different interests of the actors involved and the historical legacies complicate resolving these conflicts.

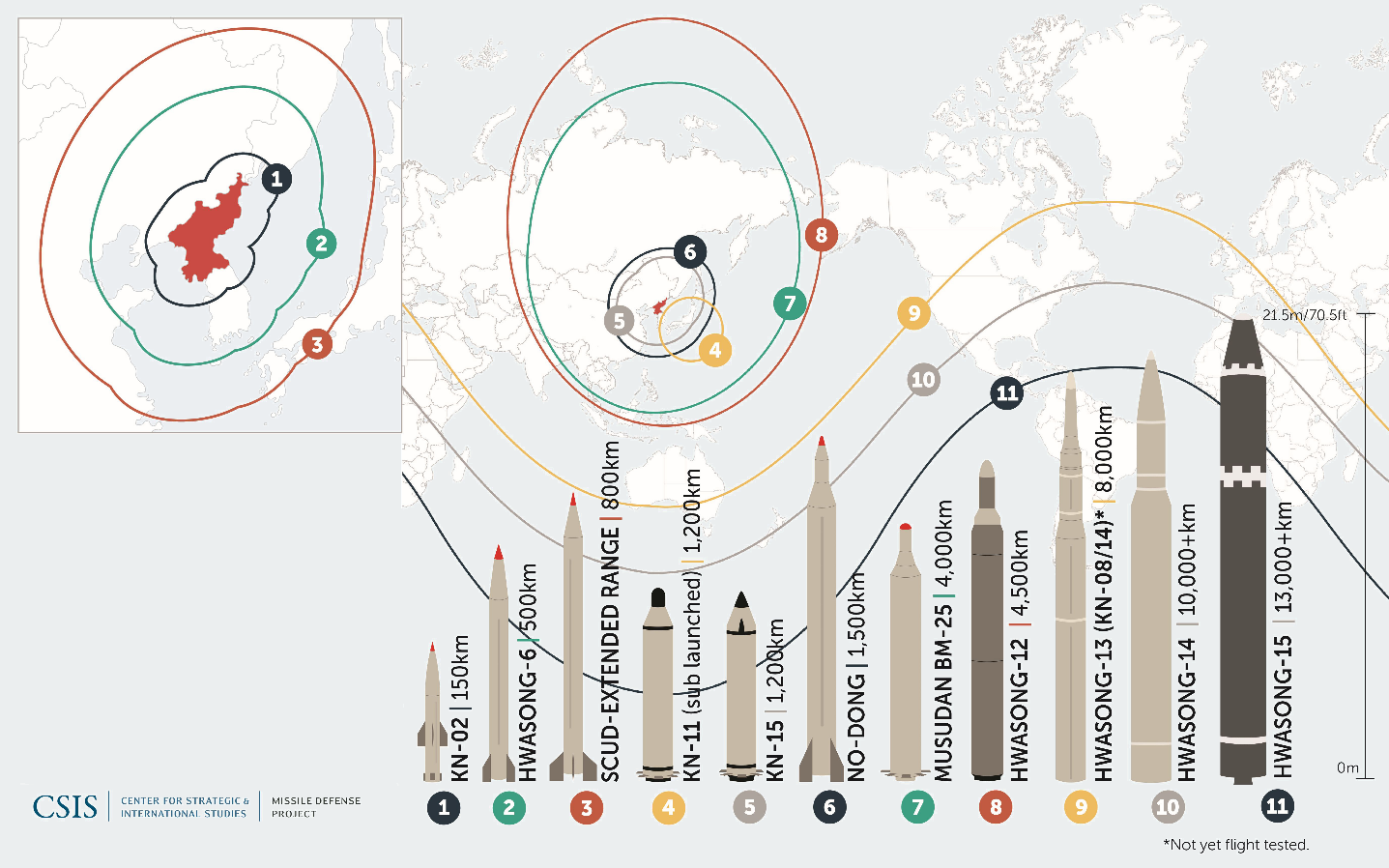

Yet it is clear that the significance of this multidimensional conflict for security and world peace can hardly be overestimated. The first issue are the living conditions of the people of North Korea, whose right to a safe and good life is persistently and massively violated by their own government. The division of Korea is also an unresolved legacy of the Cold War, which continues to cause tensions. The Korean peninsula is one of the world’s most militarised regions. Moreover, North Korea threatens its neighbourhood with its missiles and weapons of mass destruction. Following its successful tests of long-range missiles, it also represents a security risk for more distant regions: its missiles can reach North America and Europe as well. North Korea’s asymmetric military activities, for example in cyberspace, present global security with a complex and novel challenge.

Finally, there is a danger that the continued and serious violations of multilateral regulations will undermine the effectiveness and legitimacy of international governance structures. For more than 20 years, Pyongyang has provoked the international community by refusing to implement UN Security Council resolutions. North Korea has repeatedly tried to exploit the conflict between China and the USA to its own advantage. However, a united international community, and in particular a coordinated approach by the relevant major powers and North Korea’s regional neighbours, is a prerequisite for peaceful resolution of the conflict.

Focus on North Korea

Despite all this, North Korea is not the irrational hermit state it is occasionally portrayed as. Although Pyongyang’s policy tries to minimise external influences on its society, it is not isolationist.4 Even though parts of the political leadership have repeatedly had (and continue to have) international contacts, the decision-makers are socialised differently from their counterparts in most other countries. The DPRK, a totalitarian state and society ruled by a family dynasty that is now in its third generation, has developed a unique form of government.

Its political leadership views the international order solely through a hard power lens. In North Korea, military capabilities and their display hold an importance that seems anachronistic to many in the West. The fact that North Korea was the first and only state ever to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an indication that Pyongyang has an instrumental relationship towards international agreements and treaties.

At best, the government considers human rights to be of lesser importance. However, it is certainly interested in good economic development of the country, inter alia to strengthen its own position.5 This has led to a social and economic dynamic whose consequences are still difficult to assess.

In view of the multilayered nature of the North Korean conflict and the differences in the participants’ social and political understanding as outlined above, it is all the more important for any academic analysis to keep in mind the different interests and strategies of the most relevant actors, and not to reduce the conflict to dealing with North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile programmes. The various contributions collected in this study illuminate the set of problems grouped under the collective term of the “North Korea conflict” from different perspectives. They initially look at the problem of dealing with North Korea from the perspective of relevant states and their interests. The second part is dedicated to individual problem and conflict areas.

Two questions are the thread running through the respective analyses: (1) Which of the interests of the actors involved must be taken into account to achieve progress towards a sustainable, comprehensive and peaceful resolution of the conflict? And what are the lines of conflict within in different issue areas? (2) What European interests are affected, and what instruments can Europe apply to contribute to a peaceful resolution of the conflict?

This study is complemented by a dossier on the subject available on the SWP website (http://bit.ly/ SWP18DNK_Introduction). Here you will find the contributions collected in this study, other SWP analyses, and further information. By scanning the QR codes in the articles, you can go directly to the corresponding sections of the dossier.

Online dossier to the Research Paper

The North Korean Problem: A Brief History

The contributions in this study predominantly refer to the current conflict and constellation of interests. At its core, the crisis between Pyongyang and Washington is about security: North Korea sees its security threatened by the USA and believes it can only deter attacks on its sovereignty by nuclear means. The US and its regional allies are not prepared to accept such a North Korean deterrent.6

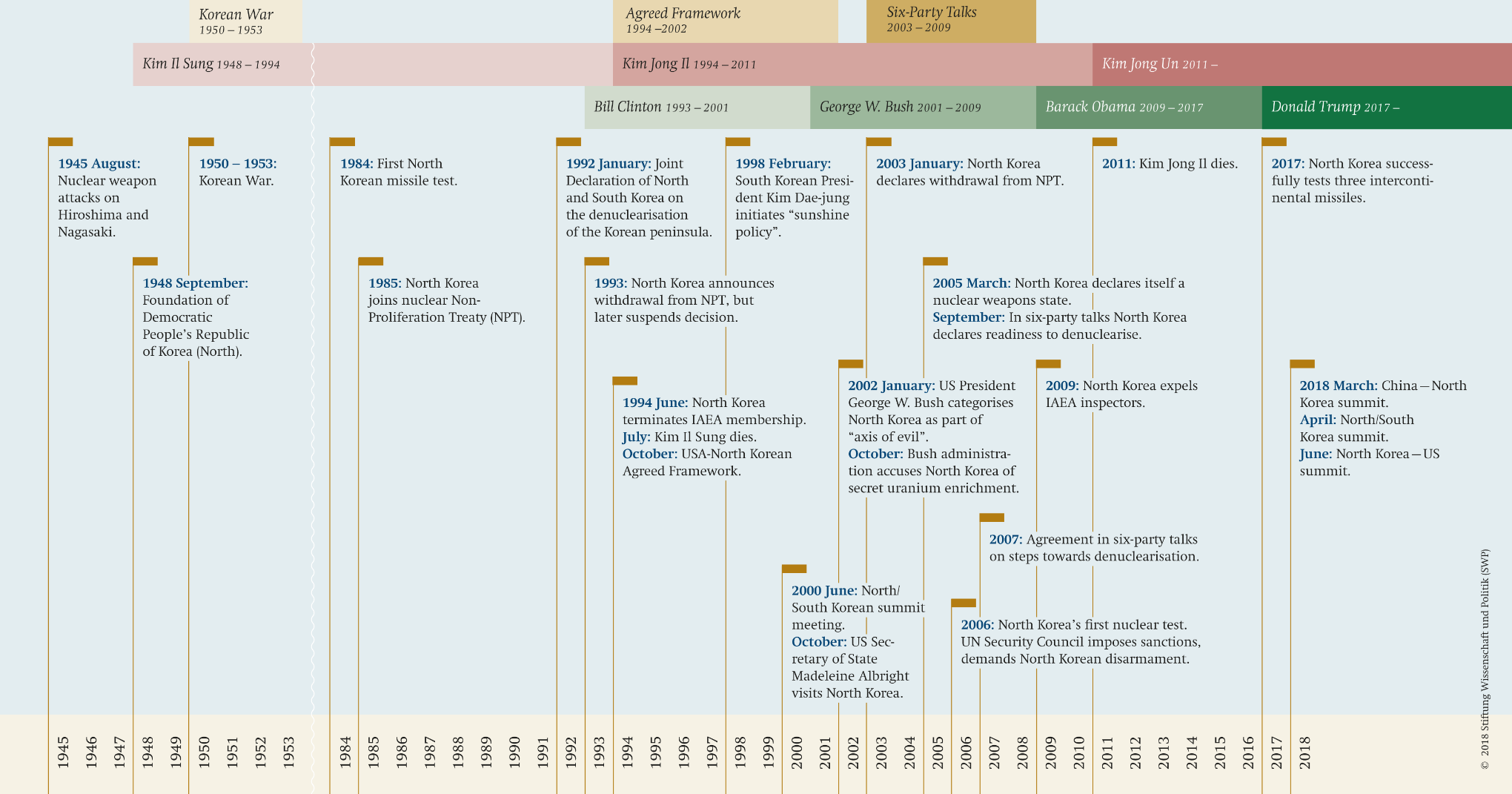

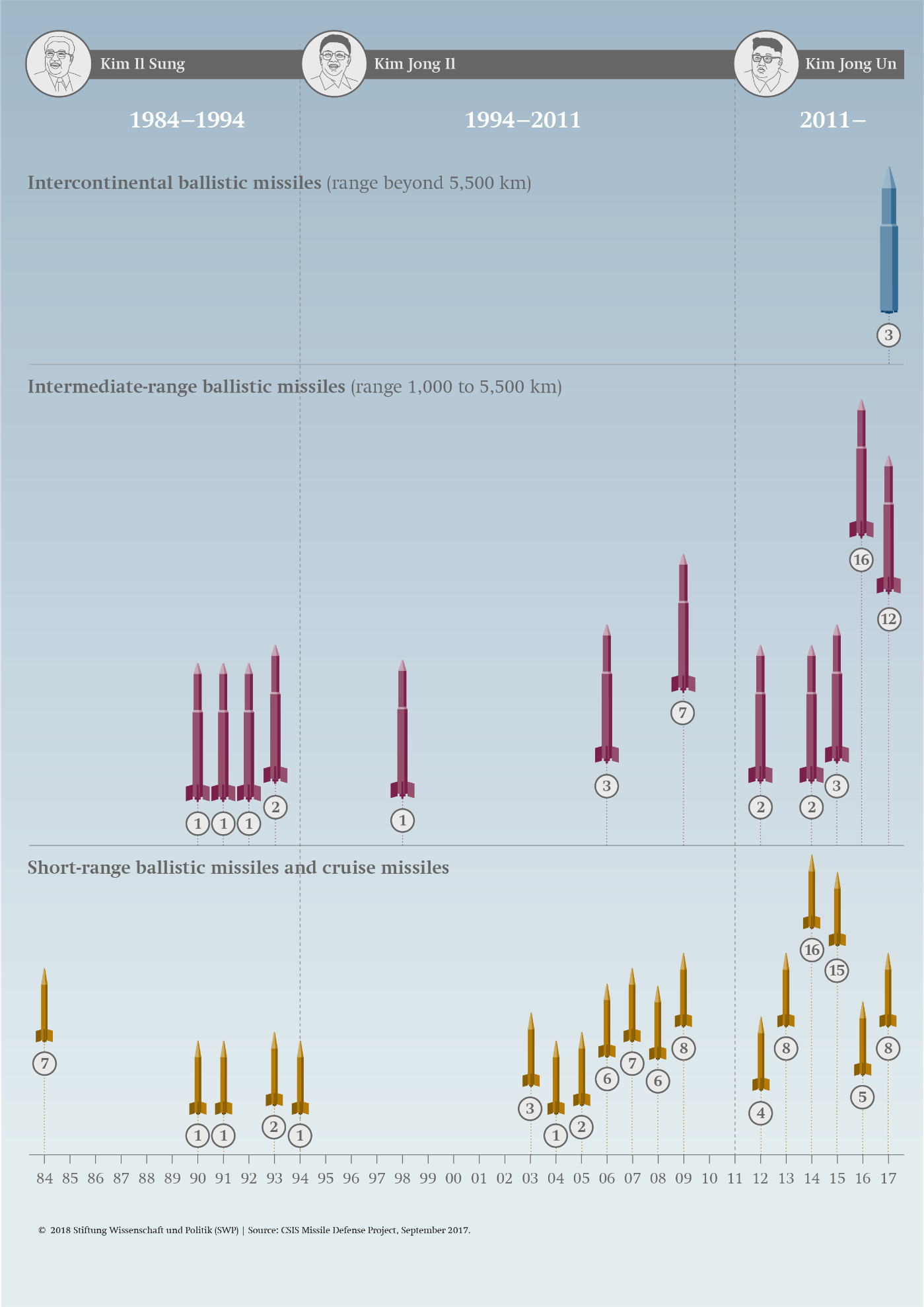

The current conflict has its roots in the Korean War (1950–53). This conflict cemented the division of Korea into a South Korea allied with the USA (Republic of Korea, RK) and a North Korea, once allied with the Soviet Union but now independent. Unlike Germany, Korea was unable to overcome this division after the end of the East-West conflict. In 1992, the IAEA detected that North Korea had secretly attempted to reprocess plutonium. Pyongyang refused special inspections by the Agency and, in 1993, for the first time announced its withdrawal from the NPT (which it subsequently “suspended”). The first nuclear crisis culminated in 1994 in North Korea’s threat to extract plutonium from spent fuel rods.7 Former US President Jimmy Carter defused the conflict during a visit to Pyongyang and thus paved the way for agreement on the 1994 Agreed Framework.8 This agreement was only possible because the USA did not insist on clarification of North Korea’s nuclear power status. North Korea declared a renunciation of nuclear weapons and in return received commitments for the annual supply of 500,000 tons of fuel oil and the construction of two light water reactors, for which purpose the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) was set up. Both sides declared that in the long term they aimed to recognise each other diplomatically and to conclude a peace treaty. The IAEA verified a “freeze” of the nuclear programme.

The second nuclear crisis began in the early 2000s, following the election of George W. Bush as US President. He placed North Korea alongside Iraq and Iran on his “axis of evil” and, in 2002, accused the country of operating secret uranium enrichment facilities. North Korea declared its withdrawal from the NPT for the second and final time. To defuse the conflict and resolve it peacefully, South Korea, China, Japan and Russia, along with North Korea and the USA, met for six-party talks lasting several years (2003–2007). The joint declarations of September 2005 and February 2007 provided a framework for settlement of the conflict whereby North Korea agreed to nuclear disarmament in exchange for aid and security guarantees. Once again, participants had not even tried to reach agreement on the question of whether North Korea was a nuclear power. However, the agreements of the six parties were not implemented. The DPRK continued its ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons programmes, and declared in April 2009, in response to the UN Security Council’s condemnation of a missile test, that it would no longer participate in the six-party talks.

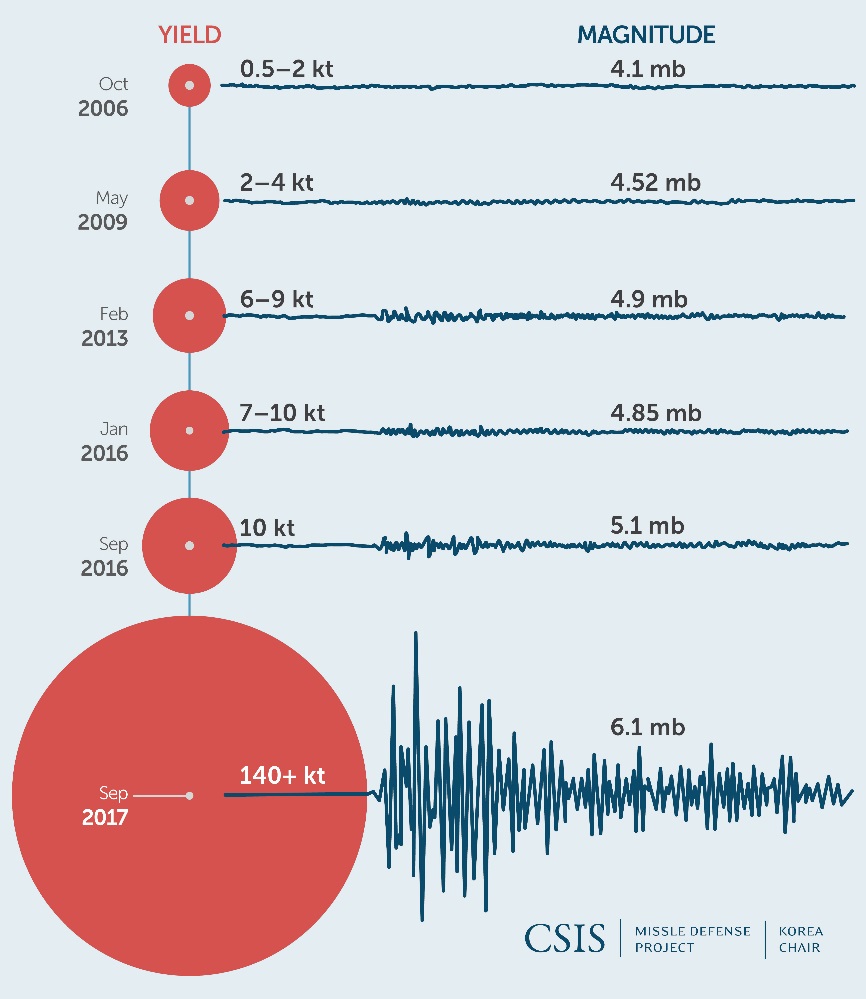

The first North Korean nuclear test in 2006 had already tipped the conflict into a new phase: the international community continued to insist on North Korea’s comprehensive, irreversible and verifiable nuclear disarmament, but the prospects for such a solution deteriorated in proportion to the progress North Korea made in its nuclear programme. US President Barack Obama’s policy of “strategic patience” was a de facto admission that the international community lacked the means to bring about the desired comprehensive disarmament.

We are currently in the third nuclear crisis, in which North Korea is pushing for reaffirmation of its own nuclear weapons possessor status. Since Kim Jong Un’s accession to power in North Korea in 2011, its nuclear and missile programmes have accelerated. In 2017, the country successfully tested three long-range missiles that could theoretically hit the US homeland.9 On this basis, Kim Jong Un announced in his New Year’s address on 1 January 2018 that he had achieved his goal of creating a nuclear deterrent against the USA.10 The USA, however, does not intend to accept such a capacity. Until the beginning of 2018, the Trump administration pursued a policy of “maximum pressure”. The Singapore summit then marked the much-publicised return to diplomacy.

Does the current situation create an opening for stabilising the situation on the Korean peninsula? Or, on the contrary, does the crisis risk worsening if diplomacy fails again? How can we in Europe contribute to preventing war in Korea and promoting the disarmament of North Korea? This study’s authors address these questions from different perspectives.

Chart 1 The development of the conflict over North Korea’s nuclear programme

Eric J. Ballbach

North Korea: Between Autonomy-Seeking and the Pursuit of Influence

North Korea’s nuclear ambitions are undoubtedly among the most pressing problems in international politics. If this challenge is to be met realistically, it is essential to make sense of the motives instructing Pyongyang’s foreign policy approach. Since an official North Korean nuclear doctrine is lacking, these driving forces can best be identified through a careful analysis of the dynamic discourse in which they occur. What basic features – and above all what changes – can be discerned? Seen from this perspective, it becomes clear that the significance of the nuclear programme for the decision-makers in Pyongyang goes far beyond security policy considerations; rather, it functions as a central component of both national identity formation and power stabilisation. The government in Pyongyang thus follows – contrary to the still widespread perception of North Korea as “inherently Other” – a rational and consistent argument based on foreign and domestic political motives.

North Korea’s Changing Patterns of Legitimisation

To understand North Korea’s motives in the nuclear question, it is essential first to identify the patterns of legitimisation postulated by Pyongyang itself with regards to its own nuclearisation strategy. This is possible because North Korea regularly provides information about its nuclear programme in the form of leadership statements, tangible legislative initiatives and legal provisions, and unveils its own driving forces in this regard. North Korea’s statements are not merely propaganda without analytical value, as is widely assumed. Instead, these explanations show a high degree of coherence, even though Pyongyang’s attempts to legitimise maintaining a nuclear programme are undergoing constant change.

Change of Discourse during the Iraq War 2003

Until the early 2000s, North Korean sources da capo emphasised that the nuclear programme was only used to generate energy and that the leadership did not seek to possess nuclear weapons. Only the Iraq War of 2003 marked a discernible turning point and the ensuing legitimacy argument for the nuclear programme changed in line with the country’s general foreign and security policy strategy. Since then, North Korea has increasingly referred to its “natural right” to produce nuclear weapons to protect the state and nation from the US’s “hostile policies”.11 A 2003 agency report on the subject declared the key lesson from the Iraq war to be that only a “powerful military deterrent” could prevent a war on the Korean peninsula and preserve the security of the Korean nation.12

North Korea’s Nuclear Breakthrough

North Korea’s first nuclear test in October 2006 represented a further crucial turning point in both the country’s foreign and security policy strategy and its main attempts at legitimising its nuclear programme. In a message addressed to national and international observers by the North Korean Foreign Ministry, the DPRK presented itself as the victim of a permanent policy of foreign aggression, which made a powerful defence capability indispensable:

“A people without reliable war deterrent are bound to meet a tragic death and the sovereignty of their country is bound to be wantonly infringed upon. […] The DPRK’s nuclear weapons will serve as reliable war deterrent for protecting the supreme interests of the state and the security of the Korean nation from the U.S. threat of aggression and averting a new war and firmly safeguarding peace and stability on the Korean peninsula under any circumstances. The DPRK will always sincerely implement its international commitment in the field of nuclear non-proliferation as a responsible nuclear weapons state.”13

As the quotation shows, this self-portrait as a responsible nuclear power plays a key role alongside the threat/defence nexus in North Korea’s attempts to legitimise its own nuclear programme. Given that North Korea’s transition to a nuclear power took place outside of international order structures following its withdrawal from the NPT, DPRK officials offered repeated assurances that the country would comply with international non-proliferation obligations. Furthermore, in November 2006, the North Korean Foreign Ministry stressed that the nuclear programme was exclusively defensive in nature and that the country would therefore never use nuclear weapons in a first strike or proliferate them.14

After the first nuclear test, North Korea repeatedly underlined the historical significance of its status as a nuclear power. The test was presented as a national event of the utmost importance: the fulfilment of the long-cherished desire for national and military strength.15 Nevertheless – and this is a crucial observation for the theoretical possibility of finding a diplomatic solution to the nuclear issue – North Korea has maximised its diplomatic leeway by repeatedly referring to its fundamental commitment to the ultimate goal of a completely denuclearised Korean peninsula.16

The Institutionalisation of Nuclear Power Status

While North Korean statements until 2008 suggest that North Korea’s transition to a nuclear power state could still be revised, the domestic discourse has changed significantly since then, in parallel with the country’s foreign policy behaviour.

On the one hand, Pyongyang has pushed its self-portrayal as a “nuclear outlaw”. North Korea, according to a Foreign Ministry spokesman, is not striving to be recognised as a nuclear power by the international community. Rather, it is content with the pride and self-confidence in being able to reliably defend the security and sovereignty of the nation.17 This line of argument is also found in the first detailed contribution to a gradually forming nuclear doctrine. A memorandum published on 21 April 2010, which also provides information on North Korea’s perception of the deterrent dynamics on the Korean peninsula, states that North Korea is not bound by the provisions of the NPT or international law. The primary mission of nuclear armament is clearly mentioned as defending against aggression and attacks on the nation. At the same time, however, the memorandum stated that the DPRK would without exception continue its policy of not using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear powers, as long as they did not participate in an invasion in cooperation with nuclear states.18

Since 2008, internal propaganda has blended North Korea’s identity with the image of a strong nuclear state.

Secondly, Pyongyang has increasingly emphasised the importance of its nuclear programme beyond mere security motives. In the critical years since 2008, domestic propaganda has closely linked the identity of the North Korean state with the image of a strong nuclear power. Especially after the death of Kim Jong Il in 2011, his political legacy was immediately merged with the country’s status as a nuclear power.19 In an article published in the party newspaper Rodong Sinmun shortly after Kim’s death, North Korea’s transition to a nuclear power was not only described as an epochal event – the historical significance of which was only surpassed by Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary struggle for liberation – but it was also praised as Kim Jong Il’s exclusive and most important achievement.20 In a constitutional amendment passed by the Supreme People’s Assembly in 2012, North Korea codified its self-proclaimed status as a nuclear power in its constitution as well. The new preamble states that Kim Jong Il transformed the DPRK into a politically and ideologically powerful nuclear state – an assessment also to be found in “Nuclear Weapons and Peace,” one of North Korea’s most significant recent texts on nuclear strategy.21 The text’s key message is unequivocal: North Korea has successfully completed the transition to nuclear power, leading also to a fundamental change in North Korea’s status within the international community. A report pub-lished by the North Korean news agency KCNA reads accordingly: “[I]f the D.P.R.K. sits at a table with the U.S., it has to be a dialogue between nuclear weapon states, not one side forcing the other to dismantle nuclear weapons”.22 These self-descriptions suggest that North Korea’s path to denuclearisation is likely to be arduous, complex and extremely costly – both politically and economically.

Since 2015/16, another key term has found its way into North Korea’s nuclear state discourse: the pre-emptive strike option. Such nuclear attacks would be conceivable if “imminent attempts to destroy North Korea” were identified. For example, Li Yong Pil, the director of a research institute on relations with the USA that is affiliated with the North Korean foreign ministry, said that nuclear pre-emptive strikes were not exclusive to the USA: “If we see that the US would do it to us, we would do it first. […] We have the technology.”23

North Korea’s Nuclear Ambitions: between Domestic and Foreign Policy Motives

Grasping North Korea’s motives in the context of the nuclear question is made more difficult by the fact that these motives are apparently not static. This notwithstanding, a careful analysis of North Korean publications and statements makes it possible to identify some key motivations, which are summarised below.

The Nuclear Programme as a Security Project

As with all nuclear powers, the security factor, understood as protection against military intervention and maintenance of state sovereignty and regime stability, is also essential for North Korea’s pursuit of its own nuclear armament. North Korea has an all-encompassing and historically consistent perception of threat. Thus, the leadership sees the country as being in a state of constant threat from outside, combined with an existential and incessant anti-imperialist struggle. In addition to historical experiences such as Japanese colonial rule or the Korean War, this threat perception was and is based in particular on the stationing of tactical US nuclear weapons in South Korea (from 1958 to 1991), the joint US-South Korean military manoeuvres that have taken place (almost) annually since 1976, and the presence of US troops in East Asia.

The perception of such a threat has further intensified since the end of the Cold War. On the one hand, developments in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to the de facto collapse of North Korea’s defence alliances with Moscow and Beijing, concluded in the 1960s. On the other hand, the repeatedly rhetorically heated relations with the USA (which in 1994 even escalated to the brink of a new war) have contributed to North Korea regarding the possession of a nuclear deterrent as an indispensable guarantor of its sovereign existence, given the military superiority of the USA and its regional allies.

Conversely, since 2012 North Korea has regularly pointed out that the nuclear programme “under the given framework conditions in East Asia” was not negotiable for the North Korean leadership (anymore). Given the existential threat to North Korea said to be posed by the USA’s foreign policy, Pyongyang repeatedly stressed that ultimately only its own nuclear deterrent had saved the country from a fate similar to that of Iraq or Libya.24 Seen in this light, regular missile and nuclear weapons tests are not provocations without any rationality, but an indispensable and inherent part of this deterrence logic. For the rulers in Pyongyang, a credible demonstration of their own deterrent potential both domestically and externally is all the more important because the logic of deterrence does not go hand in hand with an external recognition of North Korea as a nuclear power.

The Nuclear Programme as an Identity Project

The fact that immaterial factors such as national self‑confidence, prestige and pride are repeatedly addressed in the texts already shows that the significance of nuclear weapons for the rulers in Pyongyang extends far beyond military and security policy dimensions. If the analysis takes into account statements by North Korean representatives involved in direct negotiations on the nuclear project, in addition to the official declarations, it becomes clear that the nuclear programme today represents a key identity project of and for the North Korean state – even if its self-perception as a “great and strong nation” is increasingly removed from reality. Based on the perception that the country has always been under threat from outside forces and is therefore involved in a lasting anti-imperialist struggle, this identity formation is of outstanding relevance to North Korean rulers for several reasons.

These constructions serve to draw permanent boundaries between Self and Other.

These constructions serve the purpose of drawing permanent boundaries between inside and outside, between Self and Other: they “write” North Korean identity and expedite domestic political unity in the face of external enemies. Such historically consistent threat discourses continue to permeate the state’s entire rhetoric about the USA and thus contribute to normalising and institutionalising the public’s fears. Such discourses have a powerful effect, especially in authoritarian states such as North Korea, where threat discourses are strictly hegemonically controlled and access to free information is also severely limited. At the societal level, they foster the formation of a “permanent siege mentality,” which the North Korean leadership regards as a strategic component in its efforts to hold society and the political class together.25 North Korea can therefore certainly be regarded as a “camp society” in Giorgio Agamben’s sense: a society in which the state of emergency becomes a paradigm of governance and an element inherent in the leadership’s legitimisation strategy.

The omnipresent threat scenarios also suggest appropriate reactions for the state to pursue. Representations of dangers and conflicts thus serve to justify political measures aimed at containing these threats. The discourse emphasises the significance of security policy measures as well as the status of security actors, ensures the preferred supply of these actors with resources for certain national projects – be they ideological and/or political – and at the same time distracts the public from more pressing social problems. Seen in this light, the threat constructions make North Korea’s nuclear programme appear appropriate and logical from a domestic political point of view. It is more than likely that without these pronounced threat and conflict constructions, the nuclear programme in North Korea could not be maintained in the long term. For even in a totalitarian state, the implementation and maintenance of such a cost- and resource-intensive project requires a minimum of domestic legitimacy – especially in view of the multitude of urgent economic and social challenges.

The Nuclear Programme as a Historical Project

The North Korean discourse attaches outstanding historical importance to the nuclear programme. The origin of this motif lies in the experience of “national ruin,” the complete loss of state independence, sovereignty, and Korean identity through Japanese colonial rule in Korea (1910–1945). This experience represents the starting point of North Korean nation building: in addition to the demarcation from external Others, the discourse also demarks the present DPRK from its own history as a formerly colonised and militarily inferior state.26 Consequently, preventing the loss of national independence and sovereignty by all necessary means is seen as a key lesson from the experience of national ruin, which in social and political discourse is constructed as North Korea’s “Never Again”.

North Korea draws a direct line from this historical experience to the current clashes with the USA over its nuclear programme, which it has repeatedly called a “showdown” that will decide its sovereignty and independence.27 Since peace can never be guaranteed and war can only be prevented by deterrence, according to the DPRK military clout is the only option to secure these primary goals of the North Korean state.28 Locating the nuclear programme within this overarching historical frame of reference defines the confrontation with the United States to be the current chapter in Korea’s historical efforts to achieve independence and sovereignty.

The Nuclear Programme as a Bargaining Chip

In the past, the nuclear programme has time and again served the rulers in Pyongyang as a means of wringing concessions from the international community. North Korea, which to a substantial degree relies on external assistance, has repeatedly attempted to extort such assistance from abroad by strategically using foreign policy confrontations and nuclear threats. Most recently, North Korea committed itself in February 2012 in the so-called Leap Day Agreement to a moratorium on missile and nuclear tests and to returning to the negotiating table, in return for which it received food aid.29 Nevertheless, North Korea’s de facto transition to nuclear power has fundamentally changed the portents. Since then, Pyongyang has repeatedly stressed that North Korean nuclear weapons are no longer negotiable. And yet it has now promised exactly this in the wake of the recent rapprochement with the international community, which raises the question of how such policy volatility can be explained.

North Korea’s Nuclear Foreign Policy: Between Striving for Autonomy and Maximising Influence

North Korea’s foreign policy on the nuclear issue coincides in many respects with the country’s general foreign policy strategy, which is based on a “clearly realpolitik view of the world of states” and in which sovereignty and power are “the key categories in the cognitive perception and evaluation of international contexts”.30 In concrete terms, this is reflected in a dual strategy of autonomy-seeking and influence-maximising policies, which are understood as two forms of power politics.31 While an autonomy-seeking policy serves “to maintain or strengthen one’s own independence from other states”, or “to ward off new dependencies or to reduce existing dependencies on other states”, countries try to use a policy of influence to “steer certain interaction processes with other states and the policy results resulting from them in their own interest”.32 In practice, North Korea therefore relies on a defence policy whenever it considers its security or the survival of the regime to be threatened, when autonomy gains are possible, or when it risks losing autonomy compared to other states. The repeated non-compliance with, or dissolution of, existing obligations under bilateral or multilateral agreements, as well as the rejection of new obligations, are just as much a part of this as its fundamentally sceptical attitude towards cooperation, which threatens to create or strengthen asymmetric interdependencies, i.e. dependencies to the detriment of Pyongyang.

If, on the other hand, North Korea pursues a policy of influence-maximisation in the context of the nuclear issue, it seeks means that are suitable for enabling, guaranteeing and expanding its desired influence. Pyongyang therefore works to secure a voice among the more powerful states of East Asia, both bilaterally and within the framework of multilateral institutions.33

Prospects

The inter-Korean rapprochement observed since the beginning of 2018 and the resumption of a dialogue between North Korea and the USA, which culminated in a first summit meeting of the two heads of state in June 2018, have given the international community hope for a definitive and peaceful solution to the nuclear issue on the Korean peninsula. Particularly against the backdrop of the gradual escalation of tensions between North Korea and the USA, the recent rapprochement undoubtedly represents a significant step. Although both the USA and North Korea are currently making increasing reference to the possibility of denuclearising the Korean peninsula, no significant change in the discourse in North Korea has been discernible since the summit between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un. Kim Jong Un’s statement at the end of 2017 that North Korea had attained its “nuclear defence capability” is extremely significant in this context. Since then, North Korea has in fact increasingly turned to the second pillar of the national Byungjin strategy, which propagates the simultaneous development of the nuclear programme and the national economy. From Pyongyang’s perspective, given the intensified sanctions against North Korea since 2017, this makes a resumption of dialogue with the international community imperative to soften the latter’s unity on the issue of sanctions in the medium term. The probability that the nuclear programme will be completely abandoned, however, is currently rather low, for a variety of reasons: the enormous political and economic capital invested by North Korea; the continuing distrust between the actors involved; and the importance of the nuclear programme for those in power in Pyongyang which greatly transcends security factors.

Online dossier: Additional resources and SWP publications on this topic

Hanns Günther Hilpert and Elisabeth Suh

South Korea: Caught in the Middle or Mediating from the Middle?

After the liberation from its Japanese colonial rulers in 1945, the Korean peninsula was divided into two occupation zones. Following UN-mandated elections and the creation of a constitution, the American zone in the South proclaimed the Republic of Korea (RK) in 1948, while Kim Il Sung proclaimed the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the North with the support of the Soviet Union and China. The Korean War, which began in 1950 with North Korea’s invasion of the South and ended in 1953 with the Korean Armistice agreement, consolidated the confrontation between the two Korean states.

The seventy-year-long division and the de facto state of war continue to shape South Korea’s domestic and foreign policy to this day. While its military alliance with the USA has guaranteed its national sovereignty and territorial integrity, the South has definitely won the competition of political systems against the North. The Republic of Korea, with over 50 million inhabitants, has developed into a mature democracy and modern industrialised country, which ranks among high-income countries and is a member of the OECD and G20, among others.

Diverse Threats from the North

However, North Korea continues to threaten South Korea’s national security, state existence, political identity and socio-economic stability.

The DPRK regards the RK as a puppet state with a colonial-level dependency on the USA. It generally denies the South any legitimacy in national and security affairs. North Korean attempts to bring about reunification by military force, as in the Korean War, remain plausible for South Korean security politicians. Indeed, the RK has repeatedly been exposed to military aggressions from the North in the past: South Korean President Park Chung-hee survived two assassination attempts, South Korean ships were repeatedly attacked along the Northern Limit Line (NLL), and the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) along the 38th parallel was the scene of numerous military incidents. In 2010, the South Korean corvette Cheonan was sunk by a torpedo and the South Korean island of Yeonpyeong came under North Korean artillery fire. As a result, North Korea’s demands for fraternal cooperation are often met with suspicions in the South.

The military threat posed by the DPRK is both conventional and nuclear in nature. South Korea has superior military technology; in a military conflict, the more so with American support, the RK would prevail over the North in the long run. Still, South Korea fears a North Korean surprise attack – similar to the one in 2010 – or retaliation in response to an actual or perceived pre-emptive or preventive strike by the USA.34 South Korea’s capital city, Seoul, is located only 50 kilometres south of the 38th parallel and thus within immediate range of part of the approximately 15,000 artillery pieces stationed there by North Korea. According to estimates, the Seoul-Incheon metropolitan area would have to expect 400,000 to 3,800,000 civilian deaths in the event of a nuclear or thermonuclear attack.35 The entire territory of the RK is within range of North Korean short-range missiles. Nuclear warheads can be mounted on these missiles.36 The DPRK could also equip its artillery and short-range missiles with biological and chemical warfare agents.

The political and economic instability of the DPRK is the second major source of threat. Not only would a collapse of the regime pose unforeseeable security risks, but subsequent reunification would impose enormous economic costs on South Korea: to rebuild the northern part of the peninsula and to raise living conditions there. The RK itself would experience domestic conflicts due to the immense social burdens and political divisiveness.

Dilemmas

South Korea’s foreign policy constellation is extreme. The country is in the immediate neighbourhood of heavyweights China, Russia and Japan. Due to its deep integration into global markets, the RK is economically exceptionally vulnerable. Its overarching foreign policy goals – first, to ward off threats from the North; second, to maintain a thriving relationship with China despite intensifying Sino-American power competition; and third, to keep the door open to reunification with the North – are almost impossible to reconcile. Moreover, South Korea’s politics and society are deeply divided into a conservative and a progressive camp about how to deal with North Korea.

Conservatives see North Korea as an enemy and regional threat that necessitates joint action in concert with the US and the international community. They regard military deterrence and sanctions against North Korea as well as political pressure on China as proven means to denuclearise the DRPK, force reforms and enable reunification after regime collapse. In contrast, the progressives emphasise national autonomy and independence – especially in Korea’s relations with the USA – and see the North as an “impoverished compatriot” whose actions stem from insecurity. For them, dialogue and normalised relations are necessary to overcome political confrontation and allow mutual confidence-building and peace-building. In the meantime, humanitarian and economic cooperation presumably incentivise positive development in the North.37

Divergences within South Korean society weaken the coherence of its foreign policy.

This ideological division within South Korean society weakens the coherence of its foreign policy. Consequently, changes of presidency often mark turnarounds and reversals of policy.

Although the US-South Korean alliance, existing since 1953, has succeeded in reliably safeguarding the RK against the North, the alliance partners do not always agree in their threat assessments or foreign and security policy priorities. Seoul, for example, focuses primarily on the risk of war on the Korean peninsula; Washington on proliferation risks and nuclear threats to its territory.38 With regard to its ally, South Korea fears two things: an isolationist USA could withdraw from the Korean peninsula, as Donald Trump announced in his presidential election campaign and at the Singapore press conference. Or the US could disarm North Korea by military force, as security advisor John Bolton argued four weeks before his appointment.39 While the Singapore summit did ease the security situation on the Korean peninsula – at least for the time being – South Korea’s security policy remains utterly at the mercy of US actions. To make things worse, the DPRK sees the USA as the sole relevant interlocutor on security policy and particularly nuclear issues. In fact, the RK is not party to the 1953 ceasefire agreement.

South Korea’s view of China is ambivalent. The RK is economically highly dependent on China; a diplomatic solution to the conflict with North Korea, a peace regime, and future Korean reunification all require China’s endorsement. On the other hand, there are numerous reasons for scepticism and distrust.40 Above all, China’s geopolitical claim to power in Asia, the authoritarian nature of its regime, and its ambivalent North Korean policy have repeatedly shown South Korea the limits of this partnership. Although Beijing disapproves of North Korea’s nuclear armament and aggressive foreign policy behaviour, it views the conflict in the context of Sino-American superpower rivalry and prioritises stability and the seventy-year-old status quo on the Korean peninsula.

While avoiding condemnation of Pyongyang’s military aggressions in 2010, China sanctioned South Korean companies in 2016/17 following the installation of the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) missile defence system by the US in the RK. Beijing has now suspended its sanctions, but the conflict has taught Seoul not to expect China’s complacency regarding pressure on North Korea nor understanding concerning its security needs.

Options for Exerting Influence

In principle, South Korea can influence the DPRK through military deterrence, sanctions and diplomacy.

South Korea’s military deterrence and defence base on the Mutual Defence Treaty with the USA. About 28,500 US soldiers are stationed in South Korea. Together with the approximately 630,000 South Korean soldiers, they are subject to the Combined Forces Command whose wartime operational control is under US command. Joint annual manoeuvres demonstrate military strength and exercise operational readiness; these have been unilaterally suspended by President Trump at the Singapore Summit. Moreover, the US’s extended nuclear deterrence also shields the RK. In 1991, Washington withdrew all its remaining nuclear weapons from South Korea. It is the declared wish of the current Moon administration for this to remain the case.41 However, the THAAD system was newly installed in 2017, primarily to protect the southern part of the country and the US military bases stationed there. South Korea is also working on its own missile defence system. The RK’s military already has a number of drone systems, cruise missiles and self-developed ballistic missiles.42

South Korea not only implements unilateral and UN Security Council sanctions, but also proactively influences third countries in their sanctions implementation. South Korean diplomats draw foreign authorities’ attention to the activities of North Korea’s illegal networks, or protest against sanctions violations. Inter-Korean economic cooperation, once considerable, was reduced to virtually zero by the conservative administrations under Presidents Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013) and Park Geun-hye (2013–2017). In this respect, the RK has no leeway for additional sanctions of its own. However, it can provide positive incentives for the North by relaxing the sanctions regime and resuming economic cooperation.

President Moon Jae-in is convinced that talks de-escalate tensions.

For the time being, diplomacy remains the preferred tool. The progressive government under President Moon Jae-in, who assumed office in May 2017, is convinced that talks de-escalate tensions, prevent future conflicts and facilitate persuasion. President Moon’s mantra of South Korea’s leadership role in multilateral diplomacy and of pan-Korean responsibility addresses the virulent ethos of ethnic nationalism and independence in both North and South.

South Korea’s diplomacy can also exert indirect influence on North Korea. As an ally of the United States, Seoul’s security needs and preferences should be taken into account in Washington’s deliberations and decisions. It remains to be seen, however, to what extent South Korea and Japan still feature in the Trump administration’s foreign policy, which primarily emphasises US interests.

In theory, South Korea’s society, economy and politics is virtually predestined to influence North Korea on an individual and civil society level due to spatial proximity, common language and culture. However, the National Security Act of 1948 strictly controls any cross-border contacts. This inhibits South Korean civil society groups from exchange with or work in the North.43

Inter-Korean Relations

Two agreements from 1991 and 1992 remain crucial for inter-Korean relations: the “Basic Agreement” lays down the principles of improved relations and inter-Korean reconciliation; the “Joint Declaration on Denuclearisation” contains the promise of both Korean states not to produce, test or station nuclear weapons. These principles of peaceful cooperation were reinstated at the historic summit meetings of Presidents Kim Dae-jung (2000) and Roh Moo-hyun (2007) with North Korea’s then ruler Kim Jong Il. During this phase of progressive governments (1998–2008), the so-called “sunshine policy” was bilateral and multifaceted. This policy of détente, reconciliation and development produced positive results in the humanitarian and economic domains: it facilitated numerous family meetings, stabilised food supplies in the North, and allowed South Korean visitors and investors access to the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region and the Kaesong Industrial Complex.

Over the course of the Six-Party Talks, the ruling Roh administration was sympathetic to North Korea’s security demands. It remained reticent regarding the human rights situation. Despite such accommodations, however, Seoul was unable to re-direct North Korea’s foreign policy behaviour. On the contrary: North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests – most notably its first nuclear test in 2006 – contravened the South’s policy of détente. This intensified threat situation, among other things, led the ensuing conservative presidents Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye to end all policies of accommodation and strictly condition all humanitarian and economic cooperation. The sunshine policy was followed by a new ice age (2008–2017).

President Moon’s inauguration (2017) marked the return to the basic principles of the sunshine policy. The new president announced his will to initiate dialogue with the North, a diplomatic process culminating in a peace arrangement and the complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearisation of North Korea. In July 2017, in his Berlin speech, he promised to prioritise peace-building and set aside the issue of reunification. He set out for the DPRK two conditions for the North-South dialogue: an end to security provocations against South Korea and its allies, and a readiness to dialogue on the nuclear issue with the USA.

The Moon administration seeks to soften Washington’s overt scepticism vis-à-vis inter-Korean talks through transparency (with regard to its own goals and principles) and close coordination with its ally.44 Since Seoul explicitly supports the international pressure and sanctions campaign against North Korea, South Korea’s approach remains compatible with the Trump administration’s approach of “maximum pressure and engagement”. However, in a speech to parliament in November 2017, President Moon clarified that there can be no US military attack on North Korea without Seoul’s consent.

Over the course of 2017, Moon’s consistent overtures for talks initially met Pyongyang’s disinterest. However, the Winter Olympic Games in February 2018 provided an opportunity for sport diplomacy and the initiation of direct inter-Korean contact. In early March, Seoul’s special envoy delegation conveyed the agreement to hold an inter-Korean summit on 27 April in Panmunjom, on the South Korean side of the border, as well as Pyongyang’s willingness to hold a summit meeting with US President Donald Trump. North Korea had previously announced a nuclear and missile test moratorium, refrained from criticising the annual South Korean-US military exercises, and thus fulfilled Seoul’s conditions for inter-Korean dialogue. At their first summit meeting in April, Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong Un signed the Panmunjom Declaration and vowed to work towards reconciliation, peace and prosperity. Both sides agreed on the resumption of inter-Korean dialogue and cooperation, the reduction of military tensions along the demarcation line and sea borders, and joint efforts towards a peace regime. Both also declared a nuclear weapons-free Korean peninsula to be their common goal. Through the Panmunjom Declaration, the DPRK recognises the RK for the first time as a negotiating partner regarding security issues as well as a peace regime. The swiftly initiated implementation of the summit agreements, particularly the resumption of military talks whose agenda includes the withdrawal of North Korean artillery from the border line, gives cause for optimism.

The Struggle for a Voice and Co‑Determination

North Korean military threats, Chinese economic sanctions, scepticism and concern vis-à-vis Washington: most obviously in 2017, the RK was caught squarely in the middle, seemingly without support or visible influence on a national issue of existential importance. President Moon first aimed to resume dialogue with the North, pursued an active moderation and mediation strategy vis-à-vis Washington, and sought diplomatic backing in Beijing, Moscow, Tokyo, Berlin and Brussels. In the wake of inter-Korean rapprochement since the beginning of 2018, the Moon administration has shaped the public narrative concerning North Korea and dialogue with the US, repeatedly emphasising Pyongyang’s readiness to disarm and President Trump’s special (peace-promoting) role.45

The Moon administration viewed the Singapore Summit on 12 June 2018 as a confirmation of its moderation and facilitation efforts. It understands the summit agreement as a political declaration of intent to bring about denuclearisation and peace, and the explicit reference to the Panmunjom Declaration as recognition of its role. President Trump’s erratic and unpredictable policy (style) is undoubtedly also disturbing for South Korea. Neither his threat to cover North Korea with “fire and fury” nor his announcement to suspend joint military exercises indefinitely were agreed with Seoul. Still, the South’s current administration regards the Singapore Summit as a historically unique opportunity, allowing for the peaceful turn of events. The sobering insight of decreasing reliability on Washington for security, however, is fading from public debate.

Even though the overarching geopolitical confrontations and conflicting interests in the region remain unresolved and limit Seoul’s range of action, the RK has succeeded in manoeuvring itself out of a foreign policy impasse. The RK has proven capable of proactiveness, shaping public narratives and taking diplomatic action. The country has grown in stature especially vis-à-vis its heavyweight neighbours. For the DPRK, too, which prioritises economic development, the RK is an indispensable partner to balance out China. Seoul remains in the middle between all relevant actors, but seems to be effectively mediating from the middle right now.

Online dossier: Additional resources and SWP publications on this topic

Marco Overhaus

USA: Between the Extremes

Since Donald Trump took office in January 2017, US policy towards North Korea has moved between extremes. On the one hand, no American administration from Bill Clinton to Barack Obama had so openly threatened North Korea with preventative military strikes. On the other hand, before Trump, no other US president had taken the frankly courageous step of attending a summit meeting with a North Korean ruler.

At the same time, the entire political spectrum of the United States remains mistrustful of the intentions of the North Korean leadership. The failure of past negotiations since the early 1990s has reinforced Washington’s impression that the Pyongyang regime is not seriously interested in abandoning its nuclear weapons and missile programme. This distrust also has historical roots. The USA and North Korea have been hostile to each other since the Korean War (1950–1953). While this war ranks far behind Vietnam in the collective memory of the USA, it was nevertheless one of the “hardest and most casualty-heavy military conflicts in US history”.46 Although estimates of the number of victims of the Korean War vary widely, it is assumed that more than two million Koreans, 600,000 Chinese and 36,500 US soldiers died in the conflict.47

The Korean peninsula’s influence on the USA and the latter’s significance for developments there stem not least from Washington’s considerable military potential in the region. As part of its bilateral security and defence agreements, the USA stationed around 28,500 soldiers in the Republic of Korea and almost 40,000 in Japan in 2017.48 Overall, the US Pacific Command has over 375,000 soldiers and civilian forces in the India-Asia-Pacific region.49 In its Defence White Paper 2016, the South Korean Ministry of Defence estimated that in the event of a war with the North, the USA could send up to 690,000 soldiers, 160 warships and 2,000 aircraft.50

The rapprochement between Seoul and Pyongyang, which culminated in an inter-Korean summit in April 2018, and the summit meeting between the heads of state of the USA and North Korea on 12 June 2018 have boosted hopes for a diplomatic solution to the conflict over North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile programmes. For the time being, they have significantly reduced the risk of war.

However, this cannot hide the fact that the results of the meeting between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un fell far short of the expectations of even pessimistic observers. The risk of military escalation on the Korean peninsula has by no means been averted. Should the diplomatic process fail or become mired, the debate about military options in the USA will in all probability gain in virulence again.

From “Strategic Patience” to “Massive Pressure”

Since the early 1990s, successive US administrations have attempted to stop or dismantle North Korea’s nuclear programme. They used a mixture of positive and negative incentives: economic sanctions, the military expansion of alliances with regional partners, the prospect of normalising diplomatic relations, security guarantees and economic aid for North Korea. Even though the Trump administration always endeavours to make its actions seem like a radical departure from the policies of the previous administration, Obama’s policy of “strategic patience” towards North Korea and Trump’s approach of “massive pressure and engagement”51 have some things in common. Both presidents pursued and continue to pursue the goal of nuclear disarmament in North Korea, relying on bilateral and multilateral sanctions as well as China’s influence.52

The parameters and framework conditions of US policy on North Korea have changed fundamentally.

Nevertheless, the parameters and framework conditions of US policy on North Korea have changed fundamentally. First, there is the Trump factor: the President’s unpredictable political style, often expressed in twitter tirades, martial threats, or initiatives not coordinated with foreign partners or his own government, has contributed significantly to the general uncertainty about the goals and means of American policy on North Korea. In addition, the mindset of US security bureaucracy has shifted. Already during Obama’s second term in office, a pessimistic view based on realpolitik and military power prevailed in the Pentagon, in particular. Its focus was on Russia, China, Iran and North Korea, which were seen as “revisionist powers”.53 This kind of assessment complicates pursuing a policy that relies more on diplomacy.

Finally, North Korea’s surprisingly rapid progress in the development of nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missiles has significantly increased the decision-making pressure on US President Trump. Previous US administrations could still afford to postpone the problem of North Korea’s nuclear programme. When North Korea successfully tested an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) for the first time in July 2017, the US military intelligence service came to the conclusion that North Korea would be able to produce a nuclear-capable ICBM capable of reaching the USA in 2018.54 It remains unclear whether North Korea is already capable of mounting a nuclear warhead on a missile that would survive re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

In the US, it has long been the view that North Korea should not under any circumstances gain the ability to directly threaten the US with long-range nuclear missiles,55 as General Joseph Dunford,56 the US’s highest ranking soldier, reaffirmed in July 2017.57 Yet since North Korea’s successful test of an ICBM, the nuclear threat to the USA has become a reality. However, a strategy of military deterrence and containment, as practised towards the Soviet Union, Russia and China, has so far been rejected as a model for US North Korea policy.

The conviction that classic deterrence would not work in North Korea’s case is also related to US assumptions about Pyongyang’s intentions.58 From Washington’s point of view, by developing a nuclear weapons programme the regime is not only concerned with its own preservation, but also with being able to blackmail the USA and its regional allies under the protection of its own bomb (e.g. to compel US troops to withdraw from South Korea, coerce donors to supply economic aid or, in the longer term, even force through the reunification of Korea under North Korean auspices).59 The additional concern that North Korea could expedite the export of its nuclear and missile technology to the world is not only held by the Trump administration.

Diplomatic and Political Contradictions of US Policy

The Trump administration has sent out highly contradictory signals as to whether it would be prepared to engage in talks or formal negotiations with North Korea, and under what conditions.60 The US President, for example, initially denigrated the gestures of approach by South Korean President Moon Jae-in as an “appeasement policy”.61

Until March 2018, the following line seemed to prevail in the Trump administration: a moratorium was to be called on North Korean nuclear weapons and missile testing and (vague) steps to be taken towards disarmament as a precondition for initial talks (but not formal negotiations), while pressure in the shape of economic sanctions would be maintained. In March, Trump then surprisingly promised to attend a summit meeting with Kim, although fundamental US demands had not yet been met.

The course and outcome of the summit meeting between Trump and Kim on 12 June 2018 have fuelled further doubts inside and outside the US about the course US policy towards North Korea. The meeting itself was already a significant concession to North Korea, as it politically and diplomatically upgraded the regime in Pyongyang. In return, however, the USA received only vague assurances. For example, the Trump-Kim Joint Declaration does not contain a clear commitment by North Korea to complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearisation – demanded not only by the US but also by the UN – or a roadmap or review mechanism for further disarmament.62 It is clear that North Korea has so far understood the term denuclearisation to mean something fundamentally different from the USA – namely a process that also calls into question America’s extended nuclear deterrence in the region.

The impression that President Trump did not consult with his ally in Seoul concerning the announcement that the American-South Korean military exercises would be suspended, and his statements about a possible withdrawal of US troops from South Korea, also damaged the credibility of US security policy in the region.63

Against this backdrop, Trump received much criticism in Washington. Even Republican Congressmen were diffident.64 The Speaker of the House, Republican Paul Ryan, felt compelled to make it clear that the only acceptable outcome of negotiations with North Korea was “complete, verifiable irreversible denuclearisation”.65 Others in Washington even claim that the Trump administration has effectively abandoned its policy of “maximum pressure”.66 It also remains unclear how the USA will implement in detail the promise of security guarantees made to North Korea during the summit.

After the Trump-Kim Summit, the question looms of how the USA will deal with China, its most important international co-actor on North Korea. On the one hand, Trump himself has repeatedly acknowledged that the key to a diplomatic solution lies in Beijing. On the occasion of his visit to China in November 2017, he declared that the People’s Republic could solve the problem of North Korea’s nuclear programme “simply and quickly”.67 On the other hand, Trump’s China policy generally follows a confrontational course, not least with a view to his trade policy agenda, which often overlays his political and security policy requirements.68

The Debate on Military Options

The easing of the Korean conflict since the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang has also pushed the US debate about military options against North Korea into the background, at least temporarily. Previously, Trump’s multiple threats of military action against North Korea had fuelled fears both inside and outside of the region that war might result. In August 2017, the President had promised “fire and fury” and pointed out via Twitter that military solutions were available (“locked and loaded”). The threat was underpinned by other important actors both in the executive branch and in Congress. The then National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster described the tightening of sanctions as “the last best chance” to prevent a war.69 Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, a member of the Armed Forces Committee, put the probability of a military conflict on the Korean peninsula at 30 percent, based on his conversations with Trump.70

Even if the threatened US pre-emptive strikes were only a bluff, they carried considerable escalation risks.

Whether the pre-emptive strikes threatened by the White House or Congress were a bluff or not, they entailed considerable escalation risks. US debates on military options tend to be based on rather optimistic assumptions.71 The threatening military gestures from Washington also influenced the threat perception in Pyongyang. This makes military moves by the USA, for example in connection with the annual major manoeuvres in the region, appear even more dangerous from North Korea’s point of view. It also increases the risk of events developing their own momentum, and of miscalculations. One result of the Trump-Kim Summit – the announcement suspending such large-scale exercises for the time being – could thus contribute to regional security. However, such a step would be problematic without prior coordination with the US’s regional partners who rely on US security pledges.

Military alternatives to preventive strikes against the North Korean nuclear weapons programme have also been aired in Washington, though not yet at the forefront of public debate. These include, for example, establishing a sea blockade to prevent North Korea from exporting proliferation-relevant goods, and expanding military alliances as part of a strategy to deter and contain Pyongyang. Occasionally, the idea of re-stationing American nuclear weapons in South Korea is also brought back into play in Washington, for example by the former Republican chairman of the Senate Armed Forces Committee, John McCain.72 However, this option does not seem to have been adopted by the Trump administration so far.

Prospects

Since Donald Trump took office, the USA has pursued a policy of extremes. Washington has threatened military strikes against North Korea more frequently and blatantly than under previous administrations. At the same time, however, President Trump has expressed his willingness to go further than other US presidents to find a diplomatic solution to the conflict. In the past 25 years, the USA and the international community have (in vain) tried and tested almost all available diplomatic instruments to persuade North Korea to disarm – except for a summit meeting between the US President and the North Korean ruler.

In the best of all worlds, this summit diplomacy would result in a “big deal”, the actual implementation of which would ease tensions on the Korean peninsula in the years to come. North Korea would verifiably dismantle its nuclear weapons programme and in return receive security guarantees from the USA and a relaxation of international sanctions. The chances that this scenario will become reality, however, are low not only because North Korea has repeatedly promised to carry out nuclear disarmament in recent decades and has actually taken the opposite path, but also because the first US-North Korea Summit has raised considerable doubts about the goals and means of Washington’s policy on North Korea. The extent to which the Trump administration is able and willing to engage in a protracted diplomatic process with Pyongyang remains uncertain.

But even if no “big deal” is concluded, talks and negotiations between Washington and Pyongyang can help to bring about a (preferably) permanent stop to nuclear bomb and missile testing by North Korea. This would already be a great benefit because, with the current threat perception in Washington, each additional test runs the risk of provoking a harsh US counter-reaction.

However, if the diplomatic process for disarming North Korea’s nuclear and missile programme obviously fails, or becomes mired for a longer period of time, we should expect the US debate on military options to reignite. Yet sooner or later, this negative scenario would raise the question for the USA of how credible it still is to threaten military preventive or pre-emptive strikes against North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile programme. In that scenario, given the great progress made by North Korea’s programme, it would make sense for the discussion to turn instead to the issue of shaping a policy of military deterrence and containment against Pyongyang.

Online dossier: Additional resources and SWP publications on this topic

Anny Boc and Gudrun Wacker

China: Between Key Role and Marginalisation

The People’s Republic of China is often ascribed a key role, if not the key role, in solving the North Korean problem. This opinion is particularly widely held in the USA. Like previous US presidents, Donald Trump, who prioritised the issue of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programme after taking office, called on China to support him and declared that Beijing could solve the problem “easily and quickly”.73 China, North Korea’s largest trading partner and main supplier of energy and food, is believed to be best placed to exert effective pressure on the Pyongyang government. For its part, China holds the United States mainly responsible for the problem, by not taking North Korea’s security needs into account.

One of China’s most important goals, apart from denuclearising and preventing war on the Korean peninsula, is to prevent North Korea from collapsing. The summit meeting of US President Trump with the North Korean ruler Kim Jong Un in Singapore in June 2018 makes achieving all three goals seem possible, but presents China with the challenge of remaining relevant as an actor on the Korean peninsula, given its own growing rivalry with the USA.

Historical Overview