The Political Fallout of European Migration Policy in Libya

Consolidating the Detention System, Empowering Warlords and Provoking Backlash from the Libyan Public

SWP Comment 2025/C 41, 26.09.2025, 8 Seitendoi:10.18449/2025C41

ForschungsgebieteThe European Commission, Italy, and Greece are seeking to curb irregular migration through Libya. These efforts come at a time when several aspects of European Union (EU) migration policy in Libya must be acknowledged as having failed. This is particularly true of attempts to improve conditions in detention centres, and the situation of migrant workers and refugees more broadly. Most recently, a campaign by Libyan authorities against what they portrayed as EU plans to permanently settle migrants in the country showed that European policy is provoking considerable backlash. As the softer components of this policy have reached an impasse, it has been stripped to its hard core, namely arrangements with Libyan security actors to prevent departures, as well as support for interceptions at sea and returns to countries of origin. These measures are inextricably tied to Libya’s system of arbitrary detention, which serves criminal interests. European attempts to disavow this system have been unconvincing and are preventing a serious reckoning with the political costs involved.

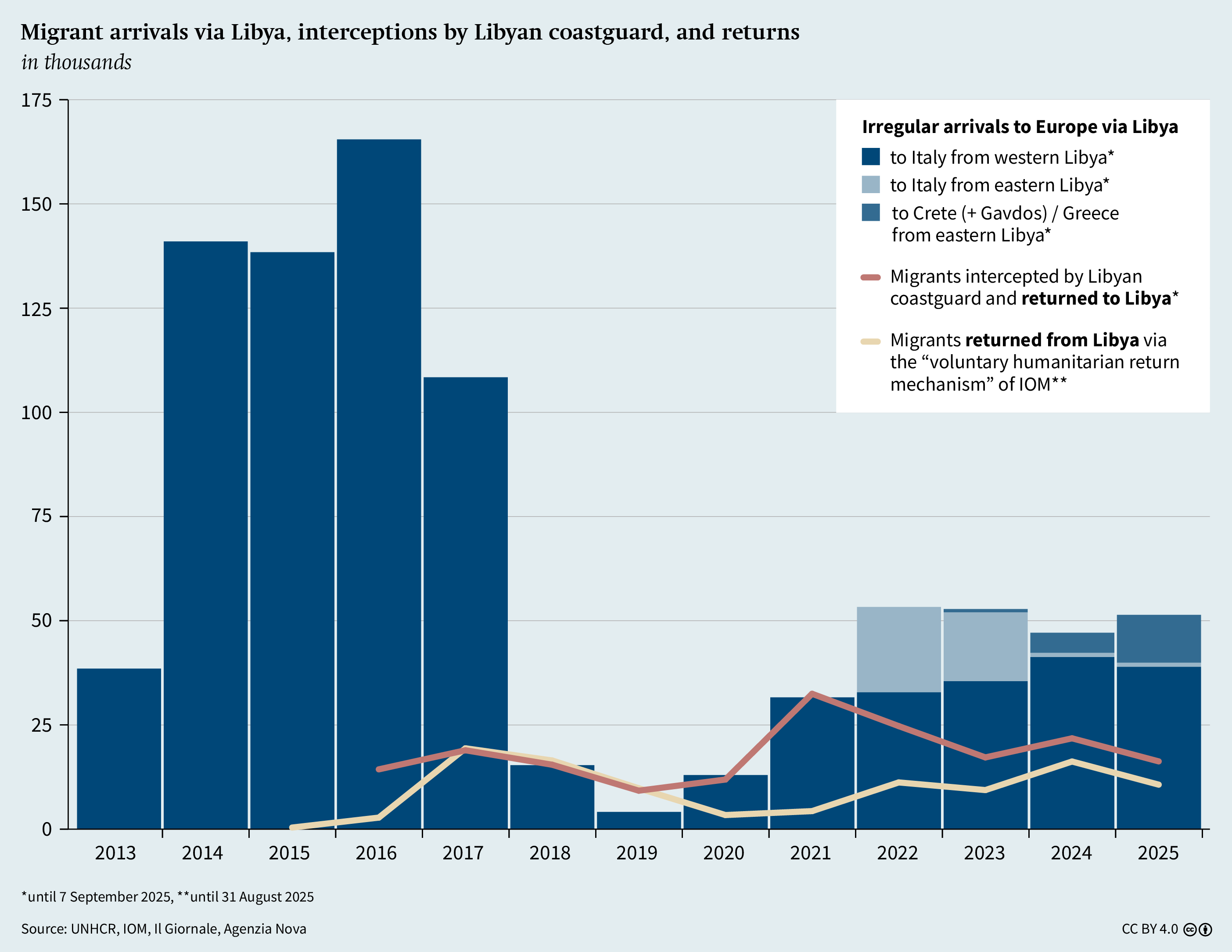

A modest rise in irregular arrivals via Libya over the past two years has prompted a flurry of European shuttle diplomacy, which intensified in the summer of 2025. Whereas irregular arrivals along other migration routes to the EU declined in the first half of the year, there was a sudden surge from eastern Libya to Crete, generating alarm in Greece. In response, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen dispatched Commissioner for Internal Affairs and Migration Magnus Brunner to Tripoli and Benghazi. Joined by ministers from Greece, Italy, and Malta, Brunner met with representatives of the internationally recognised government in Tripoli in July to press for tougher measures to block departures – without any concrete results. The subsequent visit to Benghazi was cut short after the region’s de facto ruler, Khalifa Haftar, made an audience conditional on having the delegation officially meet his parallel government, which is not internationally recognised. When the Europeans refused, they were compelled to leave. Since then, Greece has launched training programmes for Haftar’s forces, following Italy’s lead. But European efforts to court Haftar go even further. At the end of July, the EU naval operation Irini intercepted a container ship whose inspection in a Greek port found that it was carrying armoured vehicles to Benghazi. Although this was a clear violation of the United Nations (UN) arms embargo, the Greek government made sure that the vessel proceeded to Libya, apparently fearing that seizing it would jeopardise cooperation on migration. Meanwhile, crossings from eastern Libya to Crete continue, even though Haftar’s forces could prevent them.

This sequence of events illustrates the state of EU migration policy in Libya. The EU’s cooperation on migration with Libyan authorities, which it has pursued since 2017, has become increasingly ineffective, even when measured by the number of arrivals. Yet, European policymakers are doubling down on their strategy of seeking arrangements with Haftar and western Libyan militia leaders to halt departures. In doing so, they are making themselves dependent on partners who are escalating their demands. The fact that a relatively small number of arrivals in Crete – just 7,336 in the first half of 2025 – triggered such alarm in Europe is only likely to embolden actors such as Haftar to raise the price for their cooperation.

The EU’s renewed push to contain transit migration through Libya provides an opportunity to assess the workings and consequences of its migration policy in the country. Beyond Haftar’s growing demands, there are further signs that the EU’s approach is reaching its limits. Although a change of course is unlikely – given the absence of alternative strategies to reduce arrivals – a sober evaluation of the political costs is essential.

Cooperating with predatory actors

EU migration cooperation with Libya, led by Italy, includes a range of measures taken by both Italy and the EU, as well as activities financed by the EU and implemented by international organisations. Together these measures are intended to minimise the number of people arriving irregularly in the EU via Libya across the Mediterranean.

The most prominent of these measures is the Italian and European support provided to the Libyan coastguard for interception and rescue operations. Italy and the EU have supplied the coastguard with dozens of boats and ships, ensured their maintenance, and trained their personnel. With European backing, a Libyan search and rescue zone was established in late 2017 together with a Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) in Tripoli. Since then, the Italian and Maltese authorities and the EU border agency Frontex – and until 2020 also the EU naval operation Sophia – have been passing the coordinates of migrant boats primarily to the Libyan MRCC and coastguard to coordinate interception and rescue efforts.

The coastguard then transfers people it intercepts to units of the Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM). This Interior Ministry department incarcerates people in detention centres, where they face systematic abuse, torture, rape, extortion, forced labour, and often catastrophic sanitary conditions. Detention is arbitrary, since there is no legal remedy against it: Libya makes no distinction between refugees and other migrants, as the country has no asylum system and has not signed the Geneva Refugee Convention. Pregnant women and children of all ages are detained without exception. DCIM units are usually closely tied to militias, for whom detention centres represent a source of income. Business models range from embezzling state funds for operating the centres to releasing prisoners in exchange for payment and exploiting them through forced labour or prostitution. In its final report in 2023, the Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Libya, established by the UN Human Rights Council, concluded that there were reasonable grounds to believe that systematic abuse in state-run detention centres amounted to crimes against humanity, to which the EU was contributing through its support for interceptions.

European support for the coastguard has increased the likelihood of migrants being intercepted at sea. In addition, Italian and European measures have also raised the risk of drowning. Since 2018, Italy has taken numerous legal steps to obstruct or block sea rescue operations by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the Mediterranean. Germany stopped providing financial support for such operations in 2025. At the European level, patrols by Operation Sophia were suspended in 2019, and its successor – Operation Irini, established in 2020 – was never given a mandate for sea rescue missions. Irini’s area of operation was shifted to the sea off eastern Libya, which at the time was far from migration routes. In addition, regular reviews are conducted to assess whether the presence of Operation Irini’s ships could act as a pull factor for migration – as some claim – and whether the operational area should be adjusted accordingly. Such steps are justified on the grounds that they reduce the overall number of crossings, and thereby also the number of deaths. A more plausible explanation is the intention to deter crossings by increasing the risk of death, which has risen sharply. Between 2017 and 2019, the proportion of deaths during attempted crossings on the central Mediterranean route rose from 2 to 4.8 per cent. In absolute numbers, the central Mediterranean remains the world’s deadliest migration route.

Yet, without measures being taken on land, those taken at sea would have produced few meaningful results. In July 2017, arrivals from Libya suddenly dropped and then remained at a low level until 2021 (see figure). Interceptions by the Libyan coastguard were by no means the main reason for this development, as armed groups in western Libyan coastal cities had begun preventing departures. The main driver behind this shift was the prospect of gaining official status – and therefore funds – as state security forces, as well as escaping prosecution and international sanctions. Both the government in Tripoli and Italian officials used these incentives when engaging militia leaders.

This incentive structure for armed group still holds today. Operating in counter-migration offers the cover of state legitimacy, international contacts, and opportunities for enrichment through the exploitation of migrants in detention centres. However, this calculus is continually shifting as domestic power relations change and Libyan actors adjust their bargaining positions vis-à-vis Europe. A series of conflicts with the Tripoli government starting 2021 prompted armed groups in western coastal cities to once again begin facilitating migrant departures, which is one reason why arrivals from Libya have increased since 2022. Many units whose primary business model revolves around intercepting and detaining migrants maintain a foothold in smuggling networks, moving between the two markets as circumstances dictate.

The same applies to the east of the country, which is controlled by the Haftar family and, because of its geographical position, was not used for crossings until 2021. From mid-2022, thousands of people suddenly began arriving in Italy after flying to eastern Libya and departing from there on large fishing boats, with Haftar’s forces central to orchestrating these movements. The Italian government responded by officially receiving Haftar in Rome in May 2023 and offering him cooperation. Around the same time, Haftar faced negative international media coverage after the Pylos disaster in June 2023, in which more than 600 people died when a boat that had departed from eastern Libya sank. From July 2023 onward, the number of crossings from eastern Libya to Italy fell sharply, and in 2024 the numbers remained negligible (see figure). Italy has since expanded its military cooperation with Haftar’s forces. The sudden increase in arrivals from eastern Libya to Crete in the first half of 2025 also appears to have been politically motivated. As described above, Haftar sought to use his control over the migration route as leverage to improve the international standing of his parallel government. At the same time, the Haftar family has continued to profit from migration to Italy, even while preventing departures from eastern Libyan shores. The main nationalities of those arriving in Italy from western Libya in 2024 and 2025 have been Bangladeshi, Egyptian, and Pakistani, most of whom travelled via eastern Libya.

Italian officials have been claiming for several years now that arrivals from Libya are the result of deliberate Russian efforts to destabilise Europe, pointing to Russia’s military presence in Haftar’s territory. Similar concerns that Russia could politically instrumentalise migration via Libya are now being voiced within the European Commission. To date, there is no evidence to support such claims. By contrast, the Haftar family’s political instrumentalisation of migration is obvious, as is the willingness of some EU member states to accommodate the Haftars’ demands.

Multi-pronged strategy with dead ends

The EU is seeking not only to prevent crossings but also to return migrants in Libya to their countries of origin. This is done primarily via the International Organization for Migration (IOM)’s “voluntary humanitarian return” programme, through which more than 100,000 people have left Libya since 2015. This component of EU migration policy is also closely linked to the detention system since, depending on the period, between 40 and 50 per cent of IOM returnees were drawn from detention centres. Their cases could hardly be called voluntary, as this was the only way out of detention short of ransom payments. This also means that the detention system effectively serves the EU’s objective of persuading migrants to leave Libya, thereby deterring them from attempting the crossing.

Officially, the EU rejects Libya’s practice of arbitrarily detaining migrants. Since the current cooperation began in 2017, the pursuit of alternatives to detention has been a declared policy objective. Improving conditions in detention centres – while a central component of EU assistance – is presented as a stopgap measure until alternatives can be established.

But there has been no progress on alternatives to detention. Instead, the detention system and its web of financial entanglements have become further entrenched. Most recently, the Tripoli government presented the EU with a plan for a massive expansion of detentions and returns. Overcoming the detention system therefore appears completely unrealistic. This casts doubt on the rationale for ongoing efforts to improve conditions in the centres. From a humanitarian standpoint, they are essential for relieving acute suffering, even though they have done little to change the structural problems within the centres. Politically, however, they increasingly seem to be an attempt to make the system more palatable to European publics. Tellingly, the EU and its member states have increasingly toned down their demands for an end to arbitrary detention in recent years.

The final pillar of European policy is the attempt to improve the broader working and living conditions of migrants in Libya. Since 2016, the EU has spent considerable funds on this goal, for instance by financing basic services at the local level, focusing on towns along migration routes. The implementing agencies often hide the fact that these projects are designed to benefit both Libyans and migrants, and thus promote integration – since this could provoke sensitivities. At the political level, the EU has supported efforts to regulate labour migration more effectively in order to provide migrants with some form of legal protection. Labour migration to Libya and transit migration through Libya to Europe cannot be neatly separated. From a European perspective, it would therefore be sensible to provide labour migrants in Libya with greater protection and transit migrants with incentives to stay. Officially, Libyan authorities profess to share the goal of regularisation and have repeatedly announced initiatives in this direction. However, there are vested interests associated with unregulated migration, which makes it easier to exploit foreign workers. As a result, there has been no progress in this area either. This policy objective must also be regarded as unrealistic, as demonstrated by the recent backlash against European initiatives.

Campaigns and conspiracy theories

It was precisely these European efforts to improve the integration of migrants that triggered a campaign against migration and EU migration policy in Libya in the spring of 2025. The immediate cause was a communiqué on a routine meeting between the IOM country director and the minister for local administration. According to the communiqué, the discussion had focused on EU-funded projects for the protection of displaced persons and capacity-building for municipalities. On social media, however, the text was distorted and presented as a discussion about integrating migrants into local communities. Political opponents of the Tripoli government then orchestrated a media campaign claiming that the government and the EU were jointly planning to permanently settle and naturalise migrants in Libya.

Rather than dismissing rumours about such a plan, the government tried to demonstrate that it was protecting Libya from sinister foreign designs. The interior minister ordered arbitrary arrests of migrant workers on the streets and, yet again, stressed that Libya would never accept the permanent settlement of migrants. In doing so, he implied that there were indeed actors pursuing this goal. Most significantly, the Internal Security Agency (ISA) closed the offices of international NGOs implementing EU-funded projects for UNHCR and UNICEF aimed at improving migrants’ conditions and interrogated their Libyan staff. In April 2025, ISA publicly accused these organisations of working towards realising an EU plan to “settle migrants from sub-Saharan Africa” in order to undermine Libya’s social cohesion. The organisations’ work remains suspended at the time of writing.

These campaigns should be taken seriously, despite the absurdity of such allegations. After all, preventing onward migration to Europe is indeed the top EU priority. Combined with European efforts to improve conditions for migrants in Libya – and if one ignores EU financing for returns to countries of origin – it may indeed appear from a Libyan perspective that EU policy results in growing numbers of migrants in the country.

Moreover, these events should not be dismissed as an isolated overreaction by paranoid security forces. They reflect views widely shared across Libyan society – including within the top echelons of state institutions – which notably include the conviction that Libya is not a country of immigration. The public perception that the number of migrants is constantly rising is usually attributed to transit migration to Europe. This feeds into the belief that Libya was once merely a transit country but is now increasingly becoming a destination. The campaigns, therefore, have tapped into existing resentments.

The idea that Libya is only a transit country was already common under Muammar Gaddafi and remains widespread today – even though it has always been squarely at odds with reality. Libya has been a key destination for foreign workers for decades. Transit migration emerged later, but labour migration has remained the dominant form of migration, even after 2011. Without migrant workers, the Libyan economy would collapse, as Libyans avoid many manual jobs. Most of these workers come from neighbouring Egypt, Niger, Sudan, and Chad. The vast majority do not attempt to reach Europe: Nationals of Nigeria, Sudan, and Chad account for only a very small share of arrivals from Libya. And yet, European media outlets and politicians almost exclusively refer to Libya as a transit country. The large number of labour migrants often serves to fuel alarmist claims that hundreds of thousands there are only waiting to make the crossing.

Whether the number of migrants in Libya is really rising substantially is uncertain, as are the reasons for any increase, which might include a growing demand for labour or stricter prevention of departures. There are no reliable statistics. According to the IOM, the migrant population grew from around 585,000 in 2020 to 859,000 in early 2025, though these figures likely only capture part of that population. Far less credible is the claim by Tripoli’s interior minister, Emad al-Trabelsi, that the country now hosts 4 million migrants. The government has no means of counting or even estimating the migrant population. Such statements more likely reflect a general sense that migrant numbers are spiralling out of control.

Just as deeply rooted and widespread in Libya are xenophobic and racist attitudes. Migrants from sub-Saharan Africa in particular are stigmatised as carriers of disease and perpetrators of crime. The popular belief that migration is driven by sinister foreign plots also dates to the Gaddafi era. Over the years, many Libyan interlocutors have told the author that African migrants could not possibly afford the sums required for the journey to Europe, and therefore foreign organisations must be financing them. The fears and conspiracy theories voiced by the intelligence service thus resonate broadly with public opinion.

The material interests of powerful Libyan actors in both transit and labour migration are at odds with this discourse on migration. Employers – from large companies to households employing cleaners or construction workers – depend on migrant labour and prefer informal, precarious arrangements. Security forces tasked with preventing migration have an interest both in detaining migrants to extort them and in leaving routes to Europe partly open to ensure a steady supply of people to exploit. These contradictions are rarely acknowledged in public, but they are bound to feed the fears and resentments that shape Libya’s migration discourse for the foreseeable future.

Implications

The campaigns against migration and European migration policy give reason to take stock and draw conclusions from eight years of EU cooperation with Libya. Even as current signals from Europe point to an intensification of this cooperation, it has become clear that the “softer” components of EU policy have failed.

No progress has been made towards providing more protection for foreign workers. Even tentative steps in this direction have provoked backlash in Libya. Moreover, EU projects in this area have exposed Libyan employees of humanitarian organisations to significant risks. Nor has there been any progress in establishing alternatives to the arbitrary detention of migrants. On the contrary, EU-backed interceptions in the Mediterranean have supplied this system with a steady stream of detainees, and EU-funded humanitarian activities have made it more profitable for those who run it. The systematic abuses inside detention centres continue, as they are integral to the extortion-based business model. Overall, European policy has helped consolidate this system.

It remains unclear how serious the EU was about the softer elements of its migration policy in Libya. Clearly, however, it has now been reduced to its hard core, namely as measures designed to prevent migrants from crossing to Europe that are inseparable from the detention system. The EU’s official position – that it rejects this system and is seeking to find alternatives – is not credible. Both maritime interceptions and IOM returns depend on detention. Any serious discussion of European migration policy in Libya must begin with the recognition that it is fundamentally based on the detention centres and the crimes committed in them. Given the current political majorities in member states and at the EU level, this recognition alone will doubtlessly not produce a change in policy – even more so since alternative strategies are lacking towards a Libya in which warlords and criminal networks dominate state institutions. Yet, a clear-eyed view of how European migration policy actually functions in Libya is essential for assessing its political costs and consequences.

One such outcome is that the EU and its member states are empowering and legitimising Libyan warlords while also becoming increasingly dependent on them. This is most evident in their courting of Haftar, despite his record of war crimes, his alliance with Russia, and his overt use of migration control as leverage. Should Prime Minister Dabeiba in Tripoli consolidate his power further, he would likely also adopt this tactic. At the same time, the rising number of arrivals shows that Europe’s incentive structure for curbing migration is becoming less effective. The current strategy is therefore likely to deepen Europe’s dependence on Libyan warlords and prompt them to increase their demands.

The rejection of European migration policy by the Libyan public must also be counted among its political costs. Admittedly, this rejection is being driven less by actual EU measures than by how they are perceived and deliberately distorted by political actors. Still, the underlying conflict of interest is real. Preventing onward crossings keeps migrants in Libya, which is seen by the public as a growing threat. Europe’s Libyan partners, by contrast, are primarily those who profit directly from interceptions and exploitative detention.

Finally, the long-term implications for the credibility of the EU and its member states as global actors should not be underestimated. Credibility suffers when European governments, as described earlier, abet violations of the UN arms embargo in the service of migration cooperation. Most importantly, no aspect of EU migration policy contradicts its stated commitment to human rights as starkly as its reliance on detention centres as a key pillar of its policy in Libya. The longer it continues, the more it will undermine this commitment itself.

Dr Wolfram Lacher is a researcher in the Africa and Middle East Research Division. The author would like to thank Mark Schrolle for his support in data research and Nadine Biehler, Raphael Bossong, David Kipp, Isabelle Werenfels, and Azadeh Zamirirad for their feedback.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C41

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 41/2025)