The Strategic Raw Material Partnership between the EU and Zambia

Industrial Cooperation Is Key to Value Creation and Long-Term Collaboration

SWP Comment 2025/C 19, 06.05.2025, 8 Seitendoi:10.18449/2025C19

ForschungsgebieteDiversifying the supply of mineral resources is a strategic necessity – one in which resource-rich countries of the Global South play a crucial role. Zambia, which is a major global copper exporter and possesses other critical raw materials, is seeking long-term alliances that will mobilise investment and promote local value creation. The EU has taken the first step towards cooperation with the strategic raw material partnership. But if it is to remain competitive in the geopolitical arena, a stronger industrial policy foundation will be needed. That includes a coherent raw material foreign policy aligned with the “Team Europe” approach and targeted financial instruments to support industrial cooperation.

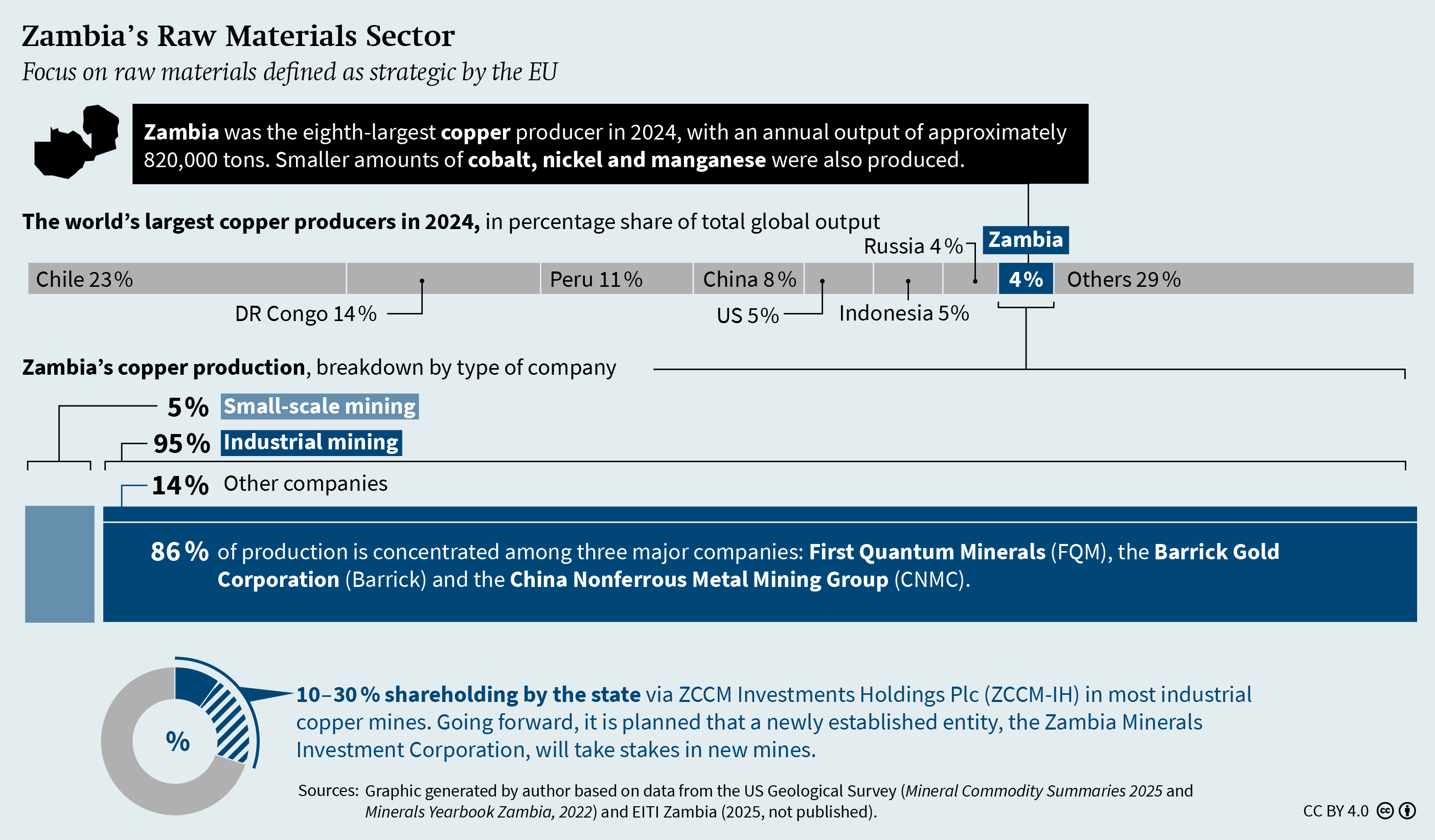

Amid rising demand for minerals and increasing geopolitical tensions, both the EU and governments around the world are actively seeking partnerships with resource-rich countries of the Global South. Zambia, which belongs to the Southern African Development Community (SADC), is currently at the centre of international raw material diplomacy. This is because of its reserves and production of copper, which is indispensable for energy and transportation infrastructure as well as electronics. Moreover, the country also has important deposits of battery raw materials such as cobalt, nickel and manganese.

Under President Hakainde Hichilema, the government is seeking to capitalise on international interest to rapidly expand Zambia’s raw material sector. China and the Gulf states are acting swiftly: the former is increasing its presence in Zambia’s mining sector, while the latter are positioning themselves as new partners. The EU, too, is seeking closer cooperation: in 2023, it signed a strategic raw material partnership with Zambia. Time is of the essence right now: if the EU wants to succeed in the global competition for raw materials, it must intensify its cooperation with Zambia, particularly in the industrial sector. This is not only the main priority for the Zambian government; it is also of strategic significance for Europe’s industrial resilience.

Strategic partnerships – including that with Zambia – need to be more firmly anchored in the overall concept of the EU’s raw material strategy. It is only in this way that the expansion of EU capacities and partnership-based cooperation in supply chains can be linked. At the same time, the EU would be offering an alternative to the protectionist policies of the United States under President Donald Trump. Indeed, the new course being followed by the US is forcing Europe to become more independent and to more decisively pursue the “Team Europe” approach.

Ambitions and challenges of the EU’s raw material partnerships

The EU’s raw material policy has significantly gained in importance in recent years. With the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) of April 2024, the EU aims to reduce dependencies and diversify its supplies – especially of the 17 raw materials identified as strategic. While the expansion of European capacities is under way, the implementation of international partnerships remains crucial if supply chains are to become more resilient.

So far, the EU has forged 14 raw material partnerships. In October 2023, it signed a legally non-binding memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Zambia as well as a similar agreement with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The EU thereby signalled to mineral-rich countries of the Global South that it wants to be a reliable and long-term partner in the raw material sector. Besides securing its own supplies, the EU is seeking to promote “win-win” cooperation that will contribute to value creation in partner countries.

The partnerships are to be implemented through the “Team Europe” approach, which involves coordinated cooperation between the EU, its member states and their financial institutions. The MoU with Zambia is now being put into practice. As part of the institutional process, the two sides have drawn up a joint implementation roadmap. The EU delegation to Zambia is now tasked with overseeing its execution on behalf of the Union, including the coordination of Member State contributions. The roadmap outlines measures in five areas:

-

Integration of supply chains (joint ventures, industrial cooperation)

-

Infrastructure financing

-

Research and innovation

-

Capacity building

-

Sustainable and responsible sourcing

The roadmap was finalised in June 2024 but, like all such roadmaps, will not be made public. One year after the signing of the MoU, the foundation for cooperation has been laid. However, Zambia’s expectations – particularly in the area of supply chain integration – have not been met. The EU must act more quickly in order to establish itself as a credible partner in what is an increasingly competitive environment. After all, Zambia is a sought-after raw material partner. Public records indicate that at least eight bilateral declarations of intent have been concluded by the government in the last two years. With his foreign policy stance of “positive neutrality”, President Hichilema, is pursuing a broad diversification strategy. Whether and to what extent these partnerships will pay off for Zambia remains to be seen. Recently, there have been two important developments.

First, neither the EU nor Zambia can regard the US as a reliable partner under the current administration in Washington. For Brussels, this is a strategic setback, as it had been counting on transatlantic cooperation, particularly within Mineral Security Partnership (MSP) initiated by the US in 2022. The goal of the MSP is to diversify raw material supply chains and reduce dependence on China through cooperation with allies. However, the results have been disappointing to date: only one copper exploration project in Zambia has been granted MSP status and there have been no further investments in the country. Under the “America First” policy, it is likely that the US will discontinue or at least scale back its engagement in the MSP; and the same applies to the joint financing of infrastructure in the region with the EU.

Second, China and the Gulf states are acting more swiftly and responding more directly to Zambia’s call for investment in its raw material sector. At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) 2024, Beijing pledged new multi-billion-dollar infrastructure investments. At the same time, China remains the largest buyer of Zambian copper while Chinese companies have announced investments totalling US$5 billion. For their part, the Gulf states are positioning themselves strategically. The United Arab Emirates has secured a key source of copper through the acquisition of the Mopani Copper Mines by International Resources Holdings. And Saudi Arabia is stepping up its raw material diplomacy: in January 2025, it signed an MoU with Zambia. Its mining investment arm, Manara Minerals, is planning to take stakes in Zambian mines and exploration projects.

Zambia’s ambitions: Mining to become growth engine

The Zambian government welcomes the growing geopolitical interest in its raw materials. Since taking office in 2021, President Hichilema has been seeking to stabilise the economy; but despite a successful debt restructuring, the country’s finances remain strained. The mining sector is expected to become Zambia’s growth engine. Indeed, it already forms the backbone of the domestic economy: in 2022, it accounted for 72 per cent of exports and 44 per cent of government revenues.

The main focus is copper production, which is already well established (see figure below). According to the government’s plan, which is being driven forward by the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Development, copper output is to increase from just over 820,000 tons in 2024 to 3 million tons by 2031; however, industry experts consider 1.5 million tons to be more realistic. At the same time, the extraction of critical raw materials is to be diversified in order to profit from global demand – especially in sectors such as the energy transition and battery production. The country’s first national Critical Minerals Strategy (CRM), presented in autumn 2024, is intended to make better use of what is the largely untapped potential of resources such as manganese, nickel and lithium. However, this will require substantial investments in exploration and the development of new mines.

To attract investors, the Hichilema government is promoting investment security and political stability. Both featured prominently at the “Insaka: Invest in Zambian Mining” conference, which took place for the first time in October 2024. Alongside Zambia’s reform plans, a new exploration programme was presented, to be carried out by Spanish firm Xcalibur and financed with US$98 million from the national budget.

To support the planned expansion of the mining sector, Zambia must also invest in infrastructure, particularly in the energy sector. More than 80 per cent of the country’s electricity comes from hydropower, which means the energy supply is vulnerable to droughts. In fact, this is currently the case, with mining and copper processing significantly affected. Nonetheless, primary processing of ore continues to take place inside the country: in 2023, besides approximately 737,000 tons of copper, Zambia produced 637,000 tons of anodes (impure copper) and 199,000 tons of cathodes (high-purity copper). While energy supply is now being stabilised through imports, coal and solar energy are expected to ensure increased stability in the future.

Furthermore, Transport infrastructure is becoming another strategic focus. Zambia has secured support for two major railway projects: the modernisation of the TAZARA railway line to Tanzania (with backing from China) and the Zambian link to the Lobito Corridor, which is planned to enhance connectivity to Angola and the DRC (US and EU).

Reform plans and state control

To achieve its expansion plans in the raw materials sector, Zambia depends on private capital. At the same time, the government is attempting a balancing act: it is striving for greater state control over the resource sector in order to benefit from the expected “commodity boom”, secure revenues for the state coffers and boost local value creation; but it wants to achieve those goals without scaring off the private sector.

In the public discourse and among large parts of civil society, the planned reforms have found widespread support, not least as a reaction against the negative consequences of privatisation in the early 2000s. However, industry players have strongly criticised the government. Despite reassurances from the administration, the Zambia Chamber of Mines, which represents private mining companies, has warned about regulatory uncertainty and potential damage to investment willingness in the country.

The debate centres on several legislative initiatives, including the Minerals Regulation Commission Act, passed in December 2024, which provides for the establishment of a new commission to regulate and oversee the mining sector. But the most controversial initiative is the planned “free equity model”, under which the state would be able to acquire stakes of up to 30 per cent in new mining projects. The stakes are to be negotiated on a project-by-project basis and managed by the newly established state-owned Zambia Minerals Investment Corporation (ZMIC). In addition, the government wants to play a more active role in metal trading. To this end, the Zambian Industrial Development Corporation has formed a joint venture with the Swiss company Mercuria.

International experts caution that growing global interest and the hope of reaping profits could push essential anti-corruption measures and effective financial governance into the background. There are signs of this already happening: it is questionable just how independent the new Minerals Regulation Commission is, while its funding is considered insufficient to improve oversight of the sector. Moreover, the planned state acquisition of stakes in new mining projects entails various risks: the state mining company ZCCM-IH has already faced allegations of political interference, while the ZMIC is more vulnerable as it is even less regulated.

Sustainability pushed into the background

The regulation of the mining sector also touches on the key issues of sustainability and standard-setting. To this day, Zambia’s mining industry continues to struggle with the grave legacies of the past, mostly environmental damage. While non-governmental organisations stress the risks of large-scale expansion, the government prioritises attracting investors – pushing sustainability into the background.

The main problem is not just regulatory gaps, but the weak enforcement. While Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) are mandated by Zambian law, they are criticised for limited scope and monitoring during project lifecycles, especially regarding mine closures and tailings management. Only recently, such a tailings dam burst once again and contaminated a major river; the long-term consequences of that incident are unforeseeable. The responsible department at the Ministry of Mines and the Zambia Environmental Management Agency are said to be too poorly equipped and too weak to successfully oppose the will of governments or even large mining companies.

In the social sphere, the framework conditions of Zambia’s industrial mining sector remain relatively stable, despite all the challenges. The country’s democratic structure allows for legal complaints and lawsuits, although enforcement continues to be difficult in practice. A particularly sensitive issue is the opening of new mines: the “social licence to operate”, meaning the public acceptance of mining projects, is often inadequately addressed in the ESIAs. Without the consent of the affected communities, social conflict and project delays are likely.

Industrial policy ambitions: Local companies and supply chains

The expansion of the mining sector is intended to strengthen local companies and promote supply chains. Those goals are enshrined in the Eighth National Development Plan (8NDP) and the new CRM strategy. But the government’s current priority is to attract mining investment rather than carry out ambitious industrial-policy projects.

Nonetheless, local industry associations are generating momentum. They have already successfully advocated for stricter local content requirements in order to increase the participation of local businesses and service providers. They are also calling for the introduction of so-called production sharing agreements (PSAs) under which mining companies would have to allocate 30 per cent of their output to be processed or manufactured locally. This is aimed, in particular, at the copper industry: in 2023, 16 per cent of domestically produced cathodes underwent further processing in Zambia, primarily into wire and cables. PSAs are intended to provide local manufacturers with stable, lower-cost access to cathodes and thereby boost their competitiveness against Asian producers. It is expected that in the long term, the model will prove profitable for other raw materials as well.

Local processing remains economically unviable for many minerals – other than copper – as they continue to be produced in too low volumes. Thus, there is significant potential for regional cooperation in the resource-rich SADC region, especially along the value chains for battery materials. Zambia and the DRC have launched a joint initiative to produce precursors and components for electric vehicles. Despite signing an MoU in 2022 and the US pledging support, progress has stalled due to diverging national interests, limited expertise, and institutional weaknesses. The escalating conflict in the DRC makes it even more difficult to pursue such regional efforts. Furthermore, there are fundamental challenges in global industrial competition: as they seek to strengthen domestic value creation, the countries of southern Africa are having to compete with China, Western industrial nations and the EU, all of which are increasingly protecting their own industries and markets.

EU-Zambia cooperation: An incomplete partnership

Zambia has precisely what Europe is strategically seeking in raw material partners – namely, critical raw materials, a democratic system and political stability. The 2023 MoU laid the groundwork; now, more rapid progress is needed. In today`s competitive environment, the EU must further develop its partnership with Zambia. Two factors complicate this effort.

First, there is a lack of strategic coherence within the “Team Europe” framework. While smaller member states such as Finland and Sweden are playing an active role, economically stronger countries like France and Germany are holding back. Moreover, coordination between Brussels, member states and EU delegations on the ground is time-consuming and frequently unfocused. This institutional fragmentation makes it hard for Zambia to grasp how the EU operates; and at the same time, it is obstructing intra-European synergies that could advance cooperation.

Second, the dearth of EU industrial projects could increasingly work against the Union in the race for partnerships. China and the Gulf states are directly addressing the typically high investment needs of in countries of the Global South and thereby positioning themselves as attractive partners. The EU, on the other hand, is currently more focused on promoting its own industries and, as a result, is missing the opportunity to involve resource-rich countries like Zambia. If it is unable to make up for lost ground, it risks losing credibility and entering into partnerships that have a limited impact.

Infrastructure and industrial cooperation: Implementation is key

Industrial cooperation was one of the more important promises the EU made to Zambia. However, it is in this area that implementation is weakest, not least with regard to infrastructure development, which is needed to facilitate resource extraction and pave the way for more industrial projects. The EU has its own instrument for promoting such undertakings in partner countries – the “Global Gateway” programme. In Zambia, however, progress has been slow and, as a result, the EU has been increasingly pushed into the background compared with China and the Gulf states.

Particular political attention is being paid to Zambia’s planned integration into the Lobito Corridor – a project initiated by the US and publicly supported by the EU. The overall project (that is, also involving Angola and the DRC) continues to receive backing from the current US administration, not least in the context of the negotiations on a “minerals for security” deal with the DRC. While Zambia’s government remains committed, the planned railway extension is a costly greenfield investment. So far, the EU has failed to make a firm financial commitment and the project is unlikely to be realised without substantial US funding.

For now, Washington’s support remains uncertain: it is not clear if the Zambian segment offers sufficient strategic value to the US, and whether the strong Chinese presence in Zambia will encourage or discourage the US. Meanwhile, the EU has to date failed to support the expansion of energy infrastructure for Zambia’s mining sector and metals industry.

Another problem is that there are only a handful of cooperation efforts under way in the raw material sector. Zambia is hoping for investments and participation in exploration, extraction and further processing; but offers from the EU are few and far between, while European companies are holding back. The “strategic project” status provided for by the CRMA could serve as a lever to generate interest among European companies for partner countries like Zambia; however, this instrument has had little impact in this regard. The first call for proposals to receive the status of “strategic project” is now closed, with only one Zambian project having taken part and no clarity on whether it will even be considered. So far, the EU commission has published only the list of projects in EU member states that have received this status. Interest among mining companies in Zambia was low, partly owing to a lack of information and partly because of insufficient financial incentives and support mechanisms.

This is by no means an isolated case; rather, it points to a structural pattern of European investment hesitation in the resource-rich countries of the Global South. In economically weaker countries, investments are often perceived as especially risky, regardless of what the situation on the ground is. High infrastructure costs and regulatory uncertainties, like those in Zambia, only compound the hesitation. The economic potential of industrial activities beyond primary extraction – such as recycling or recovering resources from tailings – remains untapped. And the very limited presence of European industry in countries like Zambia is yet another obstacle.

Improved supply-chain integration is also achievable through offtake agreements: that is, EU companies could procure strategic raw materials directly from Zambian projects, thereby bypassing opaque trading platforms and Chinese processors. For their part, Zambian state institutions are increasingly stepping forward as cooperation partners amid plans for the state to play a more active role in the sector through stakes in new mining projects and the joint venture with the Swiss commodity trader Mercuria.

In the medium and long term, regional processing is set to gain in importance, especially when the development of the battery cluster in southern Africa gets under way. At that point, Europe would be able to source more processed products from the region. However, many EU countries are prioritising their own industries while failing to provide seed funding for projects in the Global South. For this reason, there is still a lack of incentives to encourage more private sector investment. While EU-funded initiatives like AfricaMaVal or studies on the economic potential of the copper industry are important and increase visibility, they do not, of course, a substitute for market access.

Sustainability and capacity building: Leveraging strengths, boosting impact

Technical cooperation – that is, capacity building and promoting socio-ecological standards – sets the EU apart from more investment-driven actors like China and the Gulf states. Through this kind of partnership, the EU has positioned itself as an important ally for the long term. And strong institutions on the ground could help facilitate investment from Europe.

So far, the EU has focused mainly on supporting Zambia’s geological survey. Many other international partners are active in this area, too. But in order to attract investment and achieve structural improvements in the mining sector, a more targeted approach towards promoting environmental and social standards is needed. While the Zambian government is currently not prioritising regulation or enforcement, it has shown openness to change; especially after the above-mentioned environmental disaster, which is likely to push such issues into the spotlight. Here the EU can build on activities related to the environment that are already under way. On the Zambian side, it is intended that the new Minerals Regulation Commission will support better regulation including more emphasis on environmental and social standards. In addition, the state-owned mining company ZCCM-IH plans to draw up a strategy based on environmental, social and corporate governance criteria, which could generate significant momentum for the development of the mining sector as a whole.

To date, there has been no real cooperation between Zambia and the EU over the promotion of local industry and downstream supply chains. It remains unclear whether the EU is serious about pursuing deeper integration into regional value chains – for example, by supporting battery clusters. If this were indeed a strategic goal, more national and regional actors would need to be involved, especially the Zambian Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry, which is responsible for the national industrial strategy and building competitive processing industries.

Momentum towards strengthening the raw material partnership

Zambia is currently at the centre of international raw material diplomacy. The risk is that issues such as good governance and socio-ecological sustainability will be sidelined in favour of economic gain. However, severe environmental damage and demands from local stakeholders are ensuring that sustainable value creation – which is urgently needed in the country – remains an integral part of the debate. It is in this area in particular that the EU remains a reliable partner for Zambia. Through the signing of the 2023 MoU and the establishment of technical cooperation, the EU has laid a solid foundation for the partnership. And if there were to be tangible progress towards industrial cooperation, it could consolidate its position in Zambia and further diversify its own raw material supply.

For that to happen, stronger European coordination is essential. The newly created coordinator role within the EU delegation to Zambia is a first step but not enough in itself. The “Team Europe” approach must be put into practice: major European industrial nations, including Germany, should become more involved on the ground and, together, with the EU Commission, pursue a coherent strategy. Moreover, the EU should credibly signal that industrial cooperation is desired and a core component of its raw material strategy. Currently, its priority is to expand and protect its own industry, while increasingly neglecting international partnerships.

A clear sign that the EU is seriously committed to the partnerships in the region would be targeted support for industrial cooperation. An industrial policy initiative could incentivise European companies and thus have an impact in Zambia. The EU should more proactively seek to involve European companies in processing and downstream supply chains – for example, in battery materials or recycling. This would require the establishment of the appropriate framework conditions: targeted incentives and funding structures as well as reliable financing. The raw material strategy of the European Investment Bank and the financing instruments of Germany’s development bank, KfW, need to be better tailored to the requirements of both the raw material sector and developing countries like Zambia. Equally crucial are institutional structures on the ground. A more prominent role for the German Chambers of Commerce Abroad and dedicated contact persons for Zambia from the consortium EIT RawMaterials could help facilitate market entry.

The EU should make better strategic use of its unique selling point – namely, technical cooperation. A central fund, easily accessible via the EU delegation to Zambia, would be a novel tool that could accelerate the implementation of technical cooperation. Moreover, the EU should step up its support in two areas that are essential for industrial cooperation: governance – for example, through support for the new Minerals Regulation Commission and state-owned companies in the raw material sector; and industrial policy planning, which could meaningfully supplement existing programmes such as that of the World Bank. Germany could make a contribution here through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. This would allow the new coalition government in Germany to underscore its political commitment to the EU’s raw material strategy and fulfil the pledge in the coalition agreement to forge “partnerships on an equal footing”.

Meike Schulze is an Associate in the Africa and Middle East Research Division of SWP. She works on the “International Raw Material Cooperation for Sustainable and Resilient Supply Chains” project, funded by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). The following analysis is based on more than 30 interviews and expert exchanges that took place in Zambia and online between October 2024 and February 2025. The author would like to thank Melanie Müller, Veronika Jall and Inga Carry for their support and feedback on the article.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C19

(Updated English version of SWP‑Aktuell 19/2025)