Russia’s War on Ukraine and the Rise of the Middle Corridor as a Third Vector of Eurasian Connectivity

Connecting Europe and Asia via Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Turkey

SWP Comment 2022/C 64, 28.10.2022, 7 Seitendoi:10.18449/2022C64

ForschungsgebieteAmong the many significant geopolitical consequences of Russia’s war against Ukraine has been the reinvigoration of the Middle Corridor, both as a regional economic zone comprising Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Turkey but also as an increasingly attractive alternative route between Europe and China. Russia’s war has disrupted overland connectivity via the New Eurasian Land Bridge, also known as Northern Corridor, which passes through – now heavily sanctioned – Russian and Belarusian territory. While the Middle Corridor will not be able to fully replace the Northern Corridor, regional integration along the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route is likely to increase its potential at the expense of Russia in the long-term. Ankara’s close cultural ties with the Central Asian republics combined with the latter’s willingness to diversify their foreign relations away from Moscow and Beijing provide Turkey with greater leverage in the region. The EU and Turkey share a common interest in enhancing Eurasian connectivity for several reasons: to promote peace and prosperity in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, to enhance commercial access to Central Asia, to increase the resilience of European supply chains, and to diversify European energy supplies. Strengthening Eurasian connectivity would also work to balance Russian, Chinese, and Iranian influence in Central Asia.

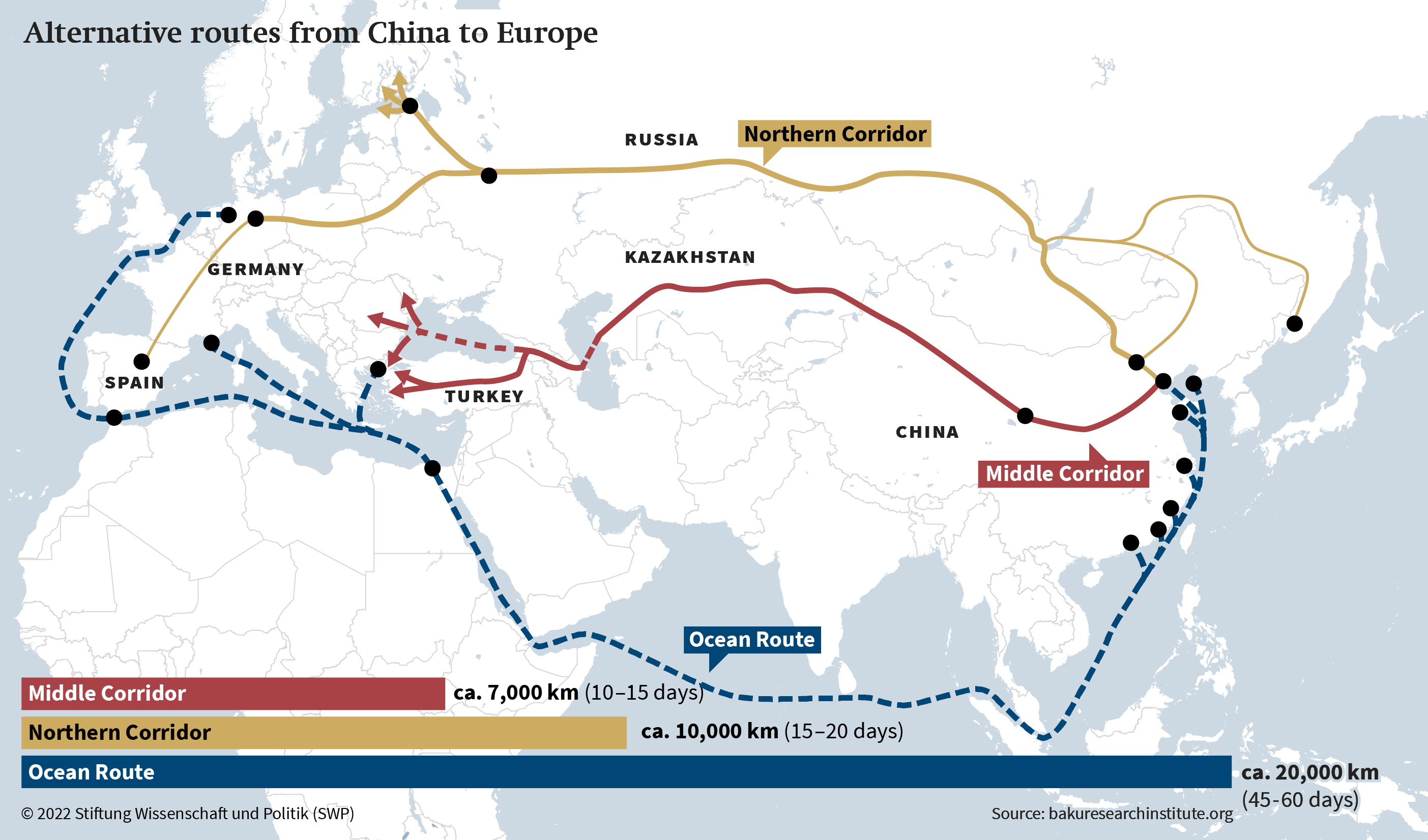

It is increasingly difficult to ship cargo between Europe and China via Russian and Belarusian territory due to recent sanctions. According to the new World Bank report, the Impact of the War in Ukraine on Global Trade and Investment (2022), logistics disruptions have affected almost all trade flows between Russia and Europe, causing significant delays and inflating already high global freight prices. China-EU shipments along the Northern Corridor, which connects China to Europe via Kazakhstan, Russia, and Belarus, have decreased by 40 per cent since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This situation has increased the appeal of Turkey’s Trans-Caspian, Middle Corridor initiative which bypasses both Russia and Iran (see Map 1, p. 2).

![]() Turkey’s Middle Corridor initiative

Turkey’s Middle Corridor initiative

The Middle Corridor is an initiative that seeks to connect Turkey to China via Georgia, Azerbaijan, the Caspian Sea, and then either 1) Kazakhstan or 2) Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. For the Asian Development Bank Institute, two major achievements of the Middle Corridor initiative are the Trans-Kazakhstan railroad, which upon completion in 2014 shaved 1,000 km off of the east-west transport route across the country, and the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) railway, which became operational in 2017. The BTK railway, or the “Iron Silk Road”, reopened direct rail transport between the Caucasus region and Turkey following the closure of the railroad between Armenia and Turkey resultant of the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict in the early 1990s. The opening of freight transportation between Azerbaijan and Turkey not only came to complete the shortest railway corridor between China and Europe but it also enhanced connectivity between Turkey and the states of Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Partially financed by the Japan International Cooperation Agency and the European Investment Bank, the Marmaray tunnel in Istanbul became the first underwater railway in the world, linking Beijing and London via the Bosporus Strait (see Map 2).

From Ankara’s perspective, the Middle Corridor is a very attractive trade route, not only because it provides a direct connection to Eurasia but also because it decreases the other Turkic states’ dependence on both Russia and Iran. The origins of the initiative date back to 2009 when the idea was proposed by Turkish ambassador Fatih Ceylan, who was then serving as Turkey’s General Director for Russia and the Caucasus. Turkey’s main objectives in launching the Middle Corridor initiative are to build an alternative multimodal route that connects Eurasia and enhances regional cooperation and coordination with the transit countries along the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route. Many advantages are foreseen in following the multimodal method, which refers to the movement of cargo from origin to destination using several modes of transportation under a single contract or bill of lading. Examples of benefits include one stop shop service, efficient shipment tracking, and the minimisation of logistics coordination expenses. Turkey aims to capture 30 per cent of the flows that pass through the Northern Corridor by diverting them to the Middle Corridor. It is promoting this through bilateral, trilateral, and multilateral initiatives that seek to take advantage of Turkey’s unique geographical position at the heart of the Europe–Asia–Africa trade triangle.

Ankara initially had difficulty convincing Central Asian countries to develop transport routes along the Middle Corridor, mostly because of the asymmetric dependence that these countries had on Russia. Therefore, the sanctions imposed on Russia following its annexation of Crimea in 2014 had increased the Central Asian countries’ interest on diversifying their foreign relations away from Moscow. Turkey’s image and reach in Central Asia have been bolstered through the country’s exhibition of hard power, especially when observing how its armed drones gave Azerbaijan a conclusive advantage over Armenia in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has also changed regional power dynamics, providing Ankara with new opportunities. While Moscow has been distracted with its war in Ukraine, Ankara has formed new strategic partnerships with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and connectivity projects have played a key role in their formation. Ankara has also become more involved in multilateral initiatives such as the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) and the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route.

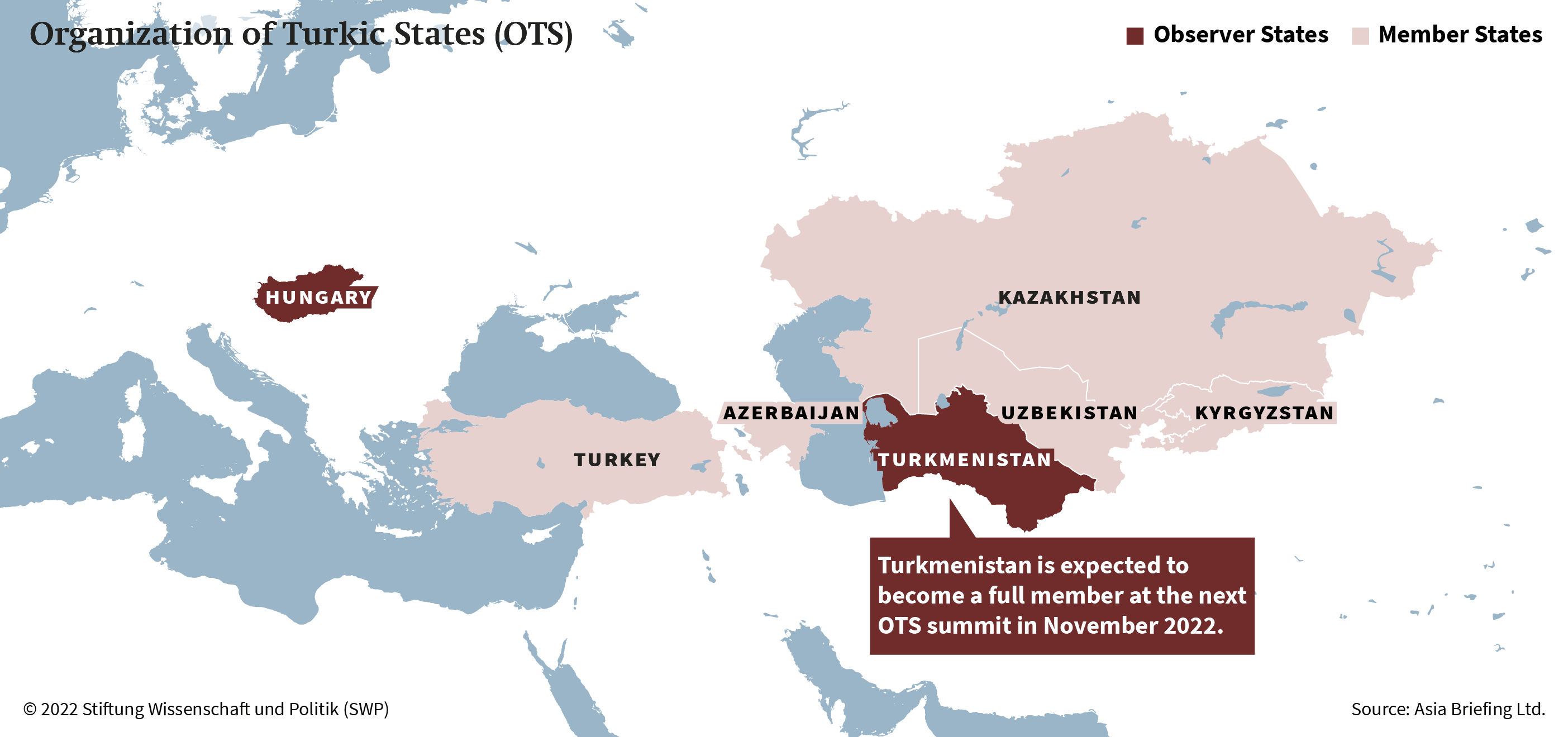

The OTS, formerly the Turkic Council, is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 2009 to promote comprehensive cooperation among Turkic language-speaking states. It is comprised of member states Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan and observer states Hungary and Turkmenistan, the latter of which is expected to become a full member on November 11. The OTC has adopted a cooperation protocol on transportation development, and in 2013 it founded a coordination council to expand regional connectivity. Last year, the OTS adopted the Turkic World Vision-2040, which seeks to incorporate member states into regional and global supply and value chains via the Middle Corridor (see Map 3, p. 4).

Turkey has also used the TITR, to promote regional connectivity. The TITR is a multilateral, multimodal transport association linking the Caspian and Black Sea ferry terminals with rail systems in China, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and eastern Europe. It links the containerised rail freight transport networks of China and the EU. The institutional development of the route dates back to 2013 when the transport organizations of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Georgia signed an Agreement on the establishment of Coordination Committee for the development of the TITR. Next year, the coordination committee was established in Astana with the participation of commercial and non-commercial transport organisations from these countries, plus Turkey. It began to officially operate as an international association in February 2017.

Regional integration along the Middle Corridor

Even before the war in Ukraine, the Middle Corridor has been gaining popularity with cargo traffic along the route increasing by 52 per cent between 2020 and 2021. Both European and Asian investors have shown significant interest in the route. For instance, Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB) paired with Pasifik Eurasia to offer a multimodal solution via the Middle Corridor in which the Köseköy Terminal near Izmit, east of Istanbul, would functions as a central hub between Asia and Europe. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing sanctions have further increased the appeal of the Middle Corridor. From January to March 2022, cargo transported along this route increased by more than 120 per cent compared to the same period in 2021. Danish shipping company Maersk, Finnish company Nurminen Logistics, Dutch logistics provider Rail Bridge Cargo, German logistic firm CEVA Logistic, Azerbaijan’s ADY container, and a group of Chinese rail operators and freight forwarders have all begun using the Middle Corridor. The volume of cargo traversing this route is expected to grow six-fold to 3.2 million metric tons in 2022 compared to 2021.

The exponential increase in demand for an alternative to Russian routes has forced regional integration and connectivity efforts to overcome technical and structural challenges that once impeded the efficient use of the Middle Corridor. The transit countries along the Middle Corridor have therefore accelerated their bilateral, trilateral, and multilateral efforts to enhance the benefits of enhanced transportation and trade connectivity since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Their efforts have focused on two main areas: expanding the psychical capacity of the Middle Corridor by adding new ports, ferries, and trains along the route, and developing soft infrastructure such as integrated customs and border management, unified regulations, and common technical standards.

In early March, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia took a positive step towards developing soft infrastructure by agreeing to align their regulations and reduce tariffs on transit cargo. Later, on March 31, 2022, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Kazakhstan decided to form a Joint Venture on the Middle Corridor that should be operational by 2023. The 2022 Action Plan elaborates the steps to be taken to facilitate transhipment processes and the smooth passage of cargo through different countries and modalities. In early May, experts from Georgia’s state railway met in Ankara with counterparts from Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan to discuss the prospects of the Middle Corridor. As a result, companies from Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan launched new feeder vessels between Georgia’s Poti and Romania’s Constanta ports.

Later in June in Baku, the foreign and transportation ministers of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan decided to form an interdepartmental working group on transport tasked with modernising technical and tariff conditions in all ports. Following the ministers’ gathering, the first meeting of the Azerbaijani-Turkish Working Group on Transport and Communications was held from June 29 to 30. The two sides discussed steps to attract additional cargo flows to the BTK railway line and the Middle Corridor. They underlined the importance of opening the Zangezur Corridor and of the construction of its continuation via the Kars–Nakhchivan railway line. The opening of the Zangezur Corridor only became possible after the settlement of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and it is important for both countries. It will not only enable Azerbaijan unrestricted access to its Nakhchivan enclave without needing to pass through any Armenian checkpoints but it will also provide Turkey a direct route to the Caspian basin and Central Asia.

On August 2, 2022, the foreign, economy, and transportation ministers of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan gathered in Tashkent to establish a new trilateral mechanism aimed at increasing coordination and cooperation among the three Turkic-speaking countries, especially on those issues related to the Middle Corridor. Here, they declared their support for connecting the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway by way of the Middle Corridor. This will create a unified transport network between the three countries along the TITR and it enable the construction of the railways and highways along the Zangezur Corridor. The completion of this project will ensure that the Middle Corridor is the shortest overland route from Asia to Europe (see Map 4, p. 6).

Finally, Turkey has undertaken new efforts to optimise shipments of cargo to southern Europe, including by putting new high-speed trains into service and by forming a quadrilateral coordination council and rail transportation working group consisting of itself, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary. Joint investment in freight transportation that develops cargo capacity and rail infrastructure while also facilitating common border procedures is likely to increase the effectiveness of the southern European portion of the Middle Corridor. The completion of the Halkali–Kapikule railway link in 2023 will reduce travel time between Istanbul and Edirne from 8 hours to 3.5 hours for freight trains and is likely to make this route more attractive for cargo coming from Asia.

Opportunities and challenges for the Middle Corridor

The long-term structural viability of the Middle Corridor must be ensured by improving its physical and soft infrastructure. It must be remembered that, by comparison, the Middle Corridor only shipped 8 per cent of the cargo volume that the trans-Siberian railway transported from Asia to Europe in 2021. Middle Corridor states and companies are beginning to direct their attention to optimising the route for future transit, including by increasing its psychical capacity and developing its soft infrastructure. Recent bilateral, trilateral, and quadrilateral efforts among the transit countries as well as the formation of new multilateral organisations indicates progress towards more coordination, particularly in areas such as customs and intergovernmental dialogue on policy. These efforts not only seek to attract freight from the Northern Corridor but also to boost regional trade and advance the economic integration of south eastern Europe, the South Caucasus, and Central Asia.

Inter-ministerial and governmental engagement among Middle Corridor countries as well as the formation of new multilateral initiatives and joint ventures including those within the Organization of Turkic States and the TITR point to the potential of integrated institutions dedicated to improved transportation and logistics. This would certainly foster the development of regional trade and industrial zones and other forms of economic integration that would benefit Central Asia, the Caucasus, Turkey, and southern Europe. In doing so, it is essential that Turkey and other Middle Corridor countries establish greater cooperation with both the EU and China, attracting more freight and much needed investment in the route’s hard and soft infrastructure. If this does not happen, the various agreements risk remaining only on paper as they fail to be translated into real politics.

Role and interest of the EU

The development of the Middle Corridor could transform the economies of Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Turkey, but until now it has been impeded by a lack of demand from the EU. This has shown signs of change, however, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has exerted significant impacts on the EU’s energy and supply-chain networks. The EU, in turn, has begun to look to Central Asia as an alternative. The EU and Azerbaijan signed a new energy deal on July 18 and they are currently negotiating a new comprehensive agreement that would allow for enhanced cooperation in a wide range of areas, including economic diversification, investment, and trade. In their joint declaration, the EU and Kazakhstan also declared that “the current geopolitical context has highlighted the need for new alternative routes that connect Asia and Europe, and connectivity has become an area of strategic importance where there is a mutual interest for further cooperation”. Moreover, on July 25, 2022, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development announced plans to invest more than US$100 million in Kazakh railways. These dynamics show that the EU is willing to explore how developing extra-regional connectivity among the Middle Corridor economies could bolster the region’s trade potential.

Today’s global supply chain reconfiguration, the European energy crisis, and the EU’s desire to seek alternatives to the trans-Siberian railway freight routes all provide the Middle Corridor countries with tremendous potential as markets and partners for the European Union. In this vein, the EU could play a key role in advising and supporting the implementation of intra- and extra-regional economic integration policies by sharing its best practices, expertise, and overall knowhow. Indeed, the EU has already developed common rules for market liberalisation and integration in the fields of technical, safety, security, and social standards as it relates to road, railway, inland waterway, aviation, maritime, and combined transport. Alignment of the Middle Corridor countries’ transport and energy policies with the EU’s green agenda and sustainable connectivity goals would benefit all parties. The long-term viability of the Middle Corridor requires political stability and effective governance in the countries along its route, but the region suffers from red tape, corruption, and broader instability stemming from border conflicts. Armenia’s inclusion in the Middle Corridor is critical for the success of the route and greater regional stability for that matter. The economic benefits that its inclusion in the Middle Corridor would bring, could deter Yerevan from seeking closer relations with Russia and Iran, and thereby contribute to long-term stability and prosperity in the South Caucasus. Whether in the form of investment or trade, Armenia stands to gain significantly from the reopening of its borders. According to Armenian Economy Minister Vahan Kerobyan, reopening Armenia’s borders and transportation routes with Turkey and Azerbaijan would allow the country’s GDP to increase by 30 per cent over the course of two years.

Within this context, the EU should increase its efforts to prevent further escalation in the South Caucasus at a time when Russian leverage in the region is weakened. Since last year, Turkey, the key supporter of Azerbaijan, has already been engaging in normalisation efforts with Armenia without preconditions, thus reinforcing a positive environment for peace and stability in the region. The two countries seem set to continue to prioritise the restoration of trade and transport routes. The EU could work to promote peace through trade in the Caucasus in consultation and coordination with its ever-contentious partner and NATO ally Turkey. The enhanced connectivity afforded by the Middle Corridor represents an opportunity for the EU and Turkey to break free from their long-standing ambivalence towards one another as they look forward to pursuing a new common purpose that fosters peace and stability in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Considering such potential benefits, the EU may see the rise of the Middle Corridor as an opportunity just waiting to be seized.

Dr Tuba Eldem is a Fellow at SWP’s Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS).

The Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) is funded by Stiftung Mercator and the German Federal Foreign Office.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2022

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2022C64