Dr. Anne Koch is an Associate in the Global Issues Division at SWP.

This research paper was prepared within the framework of the research project “Forced Displacement, Migration and Development”, funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

■ Although cross-border flight has been high on the international agenda for several years, the more wide-spread phenomenon of internal displacement has received scant political attention, despite the fact that it promotes conflict and hinders development.

■ The problem is exacerbated when internal displacement continues over an extended period. If a large population group is denied the ability to exercise its basic as well as its civil rights for years, there are high costs and political risks for society as a whole.

■ Internal displacement can have many causes. If it becomes a protracted phenomenon, this points to fundamental political shortcomings. Hence, the issue is a politically sensitive matter for the governments concerned, and many of them consider offers of international support as being undue interference in their internal affairs.

■ At the global and regional levels, legislative progress has been made since the early 2000s. However, the degree of implementation is still inadequate and there is no central international actor to address the concerns of IDPs.

■ The political will of national decision-makers is a prerequisite for the protection and support of those affected. This can be strengthened if governments are made aware of the negative consequences of internal displacement and if their own interests are appealed to.

■ The German government should pay more attention to the issue of internal displacement and make a special effort to find durable solutions. The most important institutional reform would be to reappoint a Special Representative for IDPs who would report directly to the UN Secretary-General.

Table of contents

2 Why Is There a Need for Action?

2.1 Displacement-specific Discrimination

2.3 Conflict-promoting Potential

3.1.1 Wars and Violent Conflicts

3.1.2 Natural Disasters and Slow-Onset Environmental Changes

3.1.3 Large Development and Infrastructure Projects

3.1.5 The Role of International Actors

3.2 Structural Drivers and Protracted Internal Displacement

4 Case Studies: Ethiopia and Pakistan

4.1 Reinforcement of Existing Urbanisation Trends

4.2 Shifts in Established Power Relations

4.3 Exacerbation of Societal Inequalities

5 Political and Legal Regulatory Approaches

5.1 Internal Displacement on the International Agenda

5.1.1 International Legal Foundations

5.1.2 Institutional Developments and Responsibilities

5.2 National Protection Instruments

6 Perspectives and Scope for Action for International Engagement

6.2 Entry Points in the Case of Protracted Displacement

Issues and Recommendations

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 70.3 million people world-wide were fleeing wars and violent conflicts at the end of 2018. Nearly 60 per cent of these people were so-called internally displaced persons, that is, people who were forced to leave their homes without crossing an international border. Furthermore, a far greater number of people have been displaced due to natural disasters, climate change, large-scale development projects, and organised crime, but they remain in their own countries.

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) often have a similar need for protection as cross-border refugees, but they are not entitled to international protection. Despite the alarming figures, there is a lack of political attention being given to the problems arising from internal displacement. There are a number of reasons for this. Internal displacement occurs almost exclusively in poorer regions of the world. Unlike cross-border flight, it therefore does not directly affect wealthy states, which have a major influence on the international agenda. In addition, many affected states deny the existence or extent of internal displacement, since this exposes fundamental political deficits and failures on their part. Furthermore, reliable data is scarce and the quality is poor. Since the legal status of IDPs is no different from that of their fellow citizens, and because they often live scattered throughout the country, they remain statistically “invisible”.

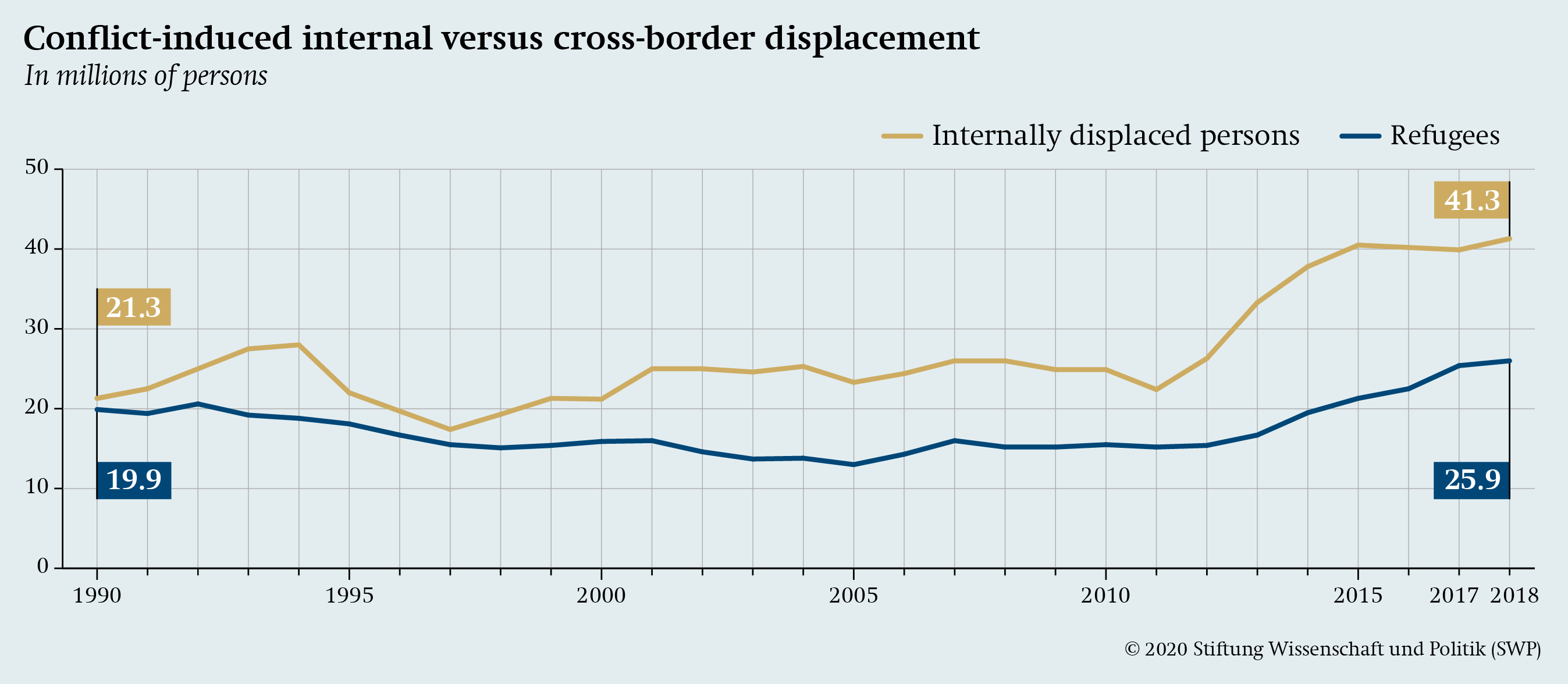

For a long time, internal displacement was considered to be primarily a humanitarian challenge. In 1998, the United Nations (UN) published its UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and expanded the prevailing view to include a human rights perspective. Although they are not legally binding, the Guiding Principles are nevertheless considered a milestone in the development of international standards of protection. There are now a variety of national and regional instruments for the protection of IDPs. However, the level of implementation remains deficient. The inadequacy of the measures taken so far is reflected in the data: The number of IDPs resulting from conflict has more than doubled since 1998.

This increase is not only due to new displacements. Equally relevant is the increasing duration of individual instances of displacement. If internal displacement becomes protracted, it is insufficient to cover only the basic material needs of those affected. In addition, access to education, livelihood opportunities, and political participation must be a priority. If this does not happen, there is a risk that the discrimination and marginalisation of large segments of the population will become permanent. In addition to individual human rights violations, structural challenges can arise: urbanisation trends intensify; demographic changes cause local or regional power structures to shift in ways that are likely to lead to conflict; and IDPs and host communities compete for resources. The resulting inequality can fuel conflicts and hamper development, thus hindering longer-term peace and reconstruction processes.

It is therefore inaccurate to view internal displacement as the unavoidable outcome of conflicts and disasters. Instead, protracted internal displacement points to deeper political distortions. When governments are unwilling or unable to meet their responsibilities to their own citizens, short-term emergencies create longer-term problems. Experiences of the past decades show that the challenges resulting from internal displacement can only be overcome with cooperation from the affected states. The central – but often missing – prerequisite for finding solutions is that the respective governments must acknowledge the problem.

This is where development-oriented arguments can make an important contribution. In essence, it is a matter of appealing to the self-interests of the affected governments. They must be made aware that internal displacement not only has negative implications for those directly affected, but that it also generates high costs for society as a whole, such as falling productivity levels, declining tax revenues, and political instability. Moreover, development policy offers the means for tackling the structural challenges associated with internal displacement.

Current efforts at the UN level to strengthen international cooperation through the Global Compact on Refugees (Global Refugee Compact) and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (Global Migration Compact) exclude the phenomenon of internal displacement. This is symptomatic of the continuing contradictions between national sovereignty and an international responsibility to stand up for those in need of protection, and the resulting fragmentation of responsibilities at the international level. It is true that more and more humanitarian, human rights, and development-oriented actors are working to remedy internal displacement. However, there is a lack of flexible and multi-annual financial resources, and there is no central actor who can bring the various perspectives together and serve as a strong political advocate for IDPs in the UN system. In January 2020, a UN High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement was set up for one year to develop new approaches. This is a positive development. However, in order to bring about longer-term changes, this initiative should be transformed into a permanent state-led process under the aegis of a group of directly affected states.

For the international community, internal displacement is a challenge whose security and developmental impacts remain underestimated. The German government should give greater priority to this issue, both at the international level and in bilateral exchanges with the countries concerned. At the international level, it would be a step in the right direction if the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons were better funded and better staffed. However, the appointment of a Special Representative on Internal Displacement, who reports directly to the UN Secretary-General, would carry much more weight. Bilaterally, the German government should work to ensure that IDPs are systematically taken into account in national development plans; it should also invest in improved data collection and analysis, and make a concerted effort to find durable solutions.

Why Is There a Need for Action?

The UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (Guiding Principles) define IDPs as “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or place of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognised State border”.1 In contrast to the legal category of (cross-border) refugees that is enshrined in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Geneva Convention), the definition in the Guiding Principles is purely descriptive and does not establish a claim for international protection. The rights of IDPs are not special rights, but rather are derived from their status as citizens or residents of a state.2 Therefore, the primary responsibility for their protection lies with the respective government.

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) estimates that 33.4 million new cases of internal displacement occurred in 2019.3 Despite these high figures, the topic receives little attention. One of the reasons for this is poor data. However, political reasons are paramount. For wealthy Western states, internal displacement is not a pressing problem, as they are not directly affected by it. According to calculations by the World Bank, at the end of 2015, 99 per cent of all IDPs resulting from conflict were in developing or emerging countries.4 In contrast to cross-border displacement, wealthy regions of the world are also not directly exposed to the consequences of internal displacement. The level of political attention is correspondingly low. The annual ranking of “forgotten crises” published by the Norwegian Refugee Council shows that major displacement incidents which remain confined within the borders of the affected country are regularly neglected by the media. It also shows that the corresponding international appeals for assistance are especially underfunded.5

Many governments deny that internal displacement occurs on their territory because they fear international sanctions or a loss of reputation.

Additionally, many governments deny that internal displacement occurs on their territory because they fear international sanctions or a loss of reputation. This is not only the case when state actors are directly involved in the displacement. Internal displacement due to natural disasters can also indicate a lack of state capacity to act, especially when displacement lasts for a long time and the situation of those affected becomes more permanent. Since the level of public interest in internal displacement is low and many governments do not admit that it exists in their country, the issue barely plays a role at the international level. This omission has far-reaching consequences. If state actors fail to fulfil their responsibility to protect IDPs, it is not only those directly affected who suffer. Society as a whole is confronted with additional costs and the threat of further conflicts, as well as the issue of onward movements across international borders.

Displacement-specific Discrimination

Although IDPs have the same legal standing as fellow citizens who are not affected by displacement, in practice they are often barred from exercising their rights. For example, forced displacement rips people out of their professional and social environments, so that livelihood opportunities and access to state services such as education and health are lost. Often, the documents required to register children at school in their new place of residence or to exercise political rights such as participating in elections are missing. The same applies for accessing the legal system, making it difficult to sue for compensation payments or the recovery of property. Those affected are often traumatised and are also at increased risk of becoming victims of sexual or other forms of violence. If they do not have a permanent place of residence, they lack the planning horizon necessary to gain a foothold again professionally. In conflict regions, IDPs have on average much higher rates of infant mortality and malnutrition than cross-border refugees and other population groups affected by conflict.6 Even if the security conditions allow for a return to the place of origin, the consequences of internal displacement are often long-lasting. This applies, for example, to cases where the original housing conditions were based on customary law or where property ownership was not sufficiently documented.

Societal Costs

Recent research findings indicate that the economic costs of internal displacement can cancel out the developmental gains that individual countries have accrued over years or decades. The direct costs and losses resulting from internal displacement alone – such as loss of income and the cost of housing, health care, education, and security – account for a substantial share of gross domestic product in some countries; in extreme cases, such as in the Central African Republic, it can be more than 10 per cent.7 There are also long-term negative effects. This includes, for example, the fact that future income and tax revenues will be reduced, since the schooling of children and young people will be interrupted or shortened due to displacement. Poorer countries are particularly hard hit by this, because their inhabitants are more vulnerable from the outset, and the negative consequences of displacement are not cushioned by personal savings or state benefits.8

Humanitarian actors have started to emphasise the developmental relevance of protracted internal displacement.

Such negative consequences are particularly serious in the case of protracted displacement or recurring cycles of displacement.9 When people are displaced several times in quick succession – which is common both as a result of violent conflict and in areas with a high risk of flooding and earthquakes – each new instance of displacement causes further losses and burdens. Humanitarian actors have started to emphasise the developmental relevance of protracted internal displacement. They argue that an effective approach to the challenges arising from this is essential if the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enshrined in Agenda 2030 are to be met.10

Conflict-promoting Potential

The link between violent conflicts and internal displacement can be reciprocal: Internal displacement is not only a regular consequence of armed conflict, but it can also contribute to the geographical expansion or shifting of conflicts.11 A number of mechanisms are at work here. When people in civil wars are displaced by state actors, those affected sometimes ally themselves with armed non-state actors. In other situations, they are defenceless against exploitation by such actors.12 Case studies from Uganda and Darfur show that places with a high density of IDPs can serve as places of refuge or as weapons depots or recruitment areas for rebel groups.13

The relevant literature lists a number of possible factors that could also link disaster-induced internal displacement to an increase in violent conflict. These include competition for scarce resources, the forced coexistence of different ethnic groups, and growing discontent when governments fail to provide adequate support to populations affected by natural disasters.14 However, a direct connection has not yet been proven empirically.15 Beyond severe human rights violations, the interplay between internal displacement and violent conflicts has particularly serious consequences in terms of foreign and security policy if it destabilises countries in the long term and leads to cross-border movements.

Causes and Trends

As with cross-border flight, internal displacement is caused by a combination of social, economic, and political drivers and acute triggers. Wars and violent conflicts, natural disasters, large infrastructure projects, and high rates of violent crime fall into the category of acute triggers. Poverty, marginalisation, and state discrimination are among the most important structural drivers. The triggers, in turn, can be divided into two categories: those that directly involve state actors and those that do not (see Table 1).16 This distinction is relevant because the question of state involvement can influence how openly state authorities deal with internal displacement, and whether or not they accept external support.

Triggers

Depending on the trigger, the quality of the available data on internal displacement varies. In principle, however, they are far less reliable than data on cross-border displacement. The available statistics are mostly projections of selectively collected data.

Wars and Violent Conflicts

The best documented cases are internal displacements due to wars and violent conflicts. In addition to direct combat operations, the fear of being recruited into (para-)military units or the loss of sources of income due to conflict can also be reasons for displacement. In the course of a civil war, ethnic minorities are often disproportionally affected and are sometimes – as was the case during the Bosnian War of the early 1990s – actively displaced as part of an “ethnic cleansing”. Civil wars generally trigger larger waves of displacement than wars between states.17 A specific dilemma is particularly pronounced in the case of conflict-induced displacement: State actors are often directly or indirectly involved in displacement, but at the same time the state is also responsible for protecting its own citizens.18 IDPs are particularly vulnerable in this situation because, unlike cross-border refugees, they are still on the territory of those responsible for their displacement, and no other authority is responsible for their protection.

State actors are often involved in conflict-induced displacement.

Figure 1 (p. 13) shows that the number of IDPs resulting from conflict fluctuated moderately between an average of 20 to 25 million from 1990 up until 2012. Since 2013, there has been a sharp rise, to more than 40 million. This was largely caused by the Syrian civil war, but the number also reflects the unstable situations in Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. The almost uninterrupted increase in the total number of IDPs due to conflict since the end of the 1990s cannot, however, be attributed solely to the new displacements that occur every year. Another reason is that durable solutions are found only for a minority of IDPs. As a result, the duration of individual instances of displacement steadily increases, meaning that the group of people affected grows from year to year.19

According to recent surveys, there are conflict-induced IDPs in 61 countries world-wide.20 However, for years a small group of states has been responsible for the vast majority of these cases. For example, at the end of 2019, more than three-quarters of all conflict-induced IDPs were in just 10 countries, at least 6 of which – Syria, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Sudan, and Iraq – have been among the 10 most-affected countries for at least five years (see Figure 2, p. 13).

|

||||||||||||

The geographic overview in Figure 2 makes it clear that, aside from in war zones, conflict-induced internal displacement occurs predominantly in states with weak governance structures. The significant overlap with the main countries of origin of cross-border refugees also indicates that, in cases of displacement, there is often a continuum between internal and cross-border movements: Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan are among the 10 most-affected countries in both categories. From a development perspective, another category of countries is of particular interest: those that are both affected by internal displacement and host large numbers of cross-border refugees from other countries. Sudan and Ethiopia, for example, are among the 10 most-affected countries world-wide in these two categories.21 In Latin America, the Venezuelan refugee crisis threatens to destabilise Colombia.

Natural Disasters and Slow-Onset Environmental Changes

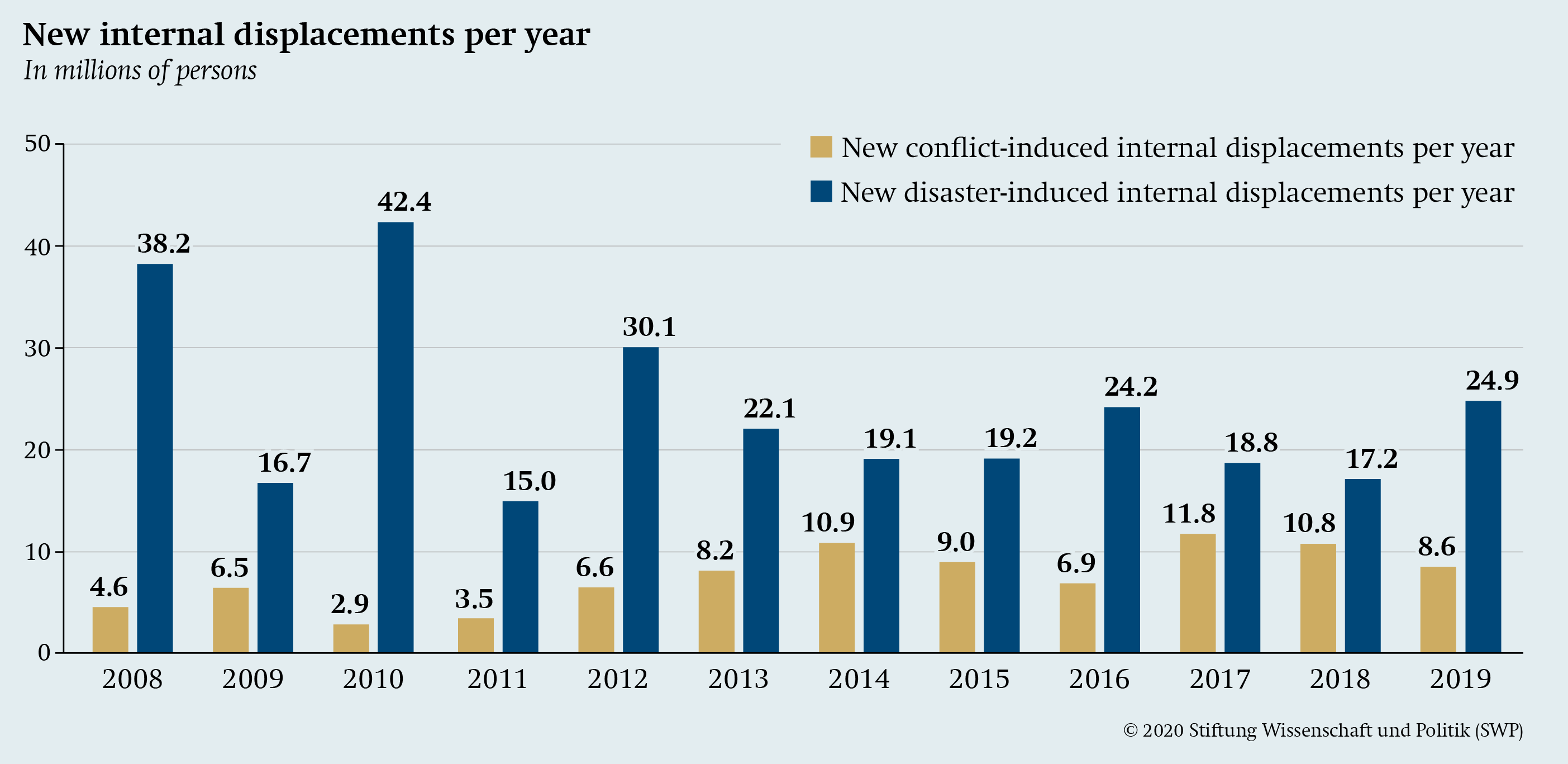

Internal displacement resulting from environmental changes is referred to as “disaster displacement”. This category includes displacement due to sudden-onset natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and forest fires, as well as forced relocation as a result of gradual environmental changes such as desertification or sea-level rise.22 So far, statistics have primarily been collected on displacements resulting from sudden-onset disasters. The available data show that, every year, far more people leave their homes as a result of natural disasters than as a result of wars and violent conflicts, and that high numbers also occur in wealthy countries such as the United States. Disaster-induced displacement is subject to greater fluctuations than conflict-induced displacement (see Figure 3, p. 14).

These strong annual fluctuations can be explained by the fact that violent conflicts gradually spread and intensify, whereas natural disasters are distinct events that cause many people to flee at a given time. In 2010, for example, floods in just two countries – China and Pakistan – forced 26.2 million people to leave their homes. This was significantly more than the total number of all disaster-induced internal displacements in 2011, a year in which there were no natural disasters of comparable dimensions.23 However, the apparent fatefulness of disaster-induced displacement often masks deeper structural disparities. Members of poor and marginalised groups, for example, are more likely to settle in flood-prone areas, live in dwellings that are not earthquake-proof, and have no reserves that would allow them to survive climate-related crop failures.24

|

Data gaps Geneva-based IDMC brings together all available data on internal displacement, making it the authoritative source for up-to-date statistics in this area. Nevertheless, the available data remain patchy. The reasons for this are manifold. On the one hand, many IDPs do not appear in the official surveys because they are scattered throughout the country and are difficult to distinguish from other poor population groups. On the other hand, the question of who is counted as an IDP depends on the national context. For example, whereas in some countries the children of IDPs are not included in the statistics, in others the status of IDP is “inherited” by the next generation – even if the original IDPs are already locally integrated or have settled permanently.a Moreover, especially in countries with weak social security systems, the support services provided for IDPs may encourage people who are not affected by displacement to register.b Finally, statistics on internal displacement always have a political dimension and are therefore used for political purposes. For example, affected governments present declining figures to demonstrate their ability to act or to prove that an internal conflict is under control. High figures, on the other hand, serve to maintain territorial claims or signal the need for support. There is a lack of standardised survey methods on internal displacement and no consensus on when internal displacement is considered to have ended. To remedy this situation, the UN Statistical Commission (UNSC) established an Expert Group on Refugee and Internally Displaced Persons Statistics (EGRIS) in 2016 to develop a comprehensive statistical framework on internal displacement.c The Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement, co-founded by UNHCR and the World Bank in October 2019, also focusses on improving the quality and availability of data on internal displacement. a See Zara Sarzin, Stocktaking of Global Forced Displacement Data, Policy Research Working Paper no. 7985 (Washington, D.C: World Bank Group, February 2017), 14. b See UN Ukraine, “Pensions for IDPs and Persons Living in the Areas Not Controlled by the Government in the East of Ukraine”, Briefing Note, February 2019, 1. c In March 2020, UNSC adopted the International Recommendations on IDP Statistics proposed by EGRIS. See https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/51st-session/documents/BG-item-3n-international-recommendations-on-IDP-statistics-E.pdf (accessed 20 April 2020). |

Like conflict-induced displacement, the bulk of disaster-induced displacement is concentrated in a small group of countries. In 2019, for example, more than 80 per cent of the new cases arising were from just 10 countries. Most of these are located in South-East Asia and the Pacific, as many countries in these regions are affected by seasonal storms and flooding.25 A number of countries have high rates of both conflict-induced and disaster-induced internal displacement. In Africa these include Ethiopia, Niger, Nigeria, South Sudan, and Sudan, and in Asia include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines.26

Large Development and Infrastructure Projects

Large-scale projects designed to promote the economic development of a country often involve the resettlement of certain population groups. This is a relatively well-documented phenomenon in the construction of dams. Especially in India and China, entire regions have been flooded.27 Urban renewal initiatives, mining projects, and infrastructure projects such as the construction of railway lines may also mean that people have to leave their homesteads. Reliable figures do not exist, but estimates suggest that 10 to 15 million people are affected every year.28 Particularly in strongly affected countries, government agencies refuse to categorise this form of migration as internal displacement, as it is deemed to be an inevitable outcome of modernisation efforts and because, ideally, a balance has been struck between the interests of the affected residents and the interests of the population as a whole.29

|

In 2019, the number of conflict-induced IDPs increased to 45.7 million Source: IDMC |

Indeed, there are relevant differences between conflict- and disaster-induced internal displacements. Extensive development projects go through a planning phase; the necessary relocations are therefore announced in advance. This allows for an orderly process, and the state or the respective executing agency can make compensation payments or provide new accommodations. Nevertheless, resettlement can constitute a form of displacement if it takes place under duress or if there is no adequate compensation. Like other types of internal displacement, this mostly affects poor and marginalised population groups who are not able to influence political decisions in their favour. This is the case, for example, when urban slums are cleared to make room for expensive new housing, or when indigenous populations are forced to leave their ancestral lands to allow for the exploitation of mineral resources. In addition, particularly disadvantaged people often have no formal land titles or cannot refer to land registry entries and are therefore sometimes evicted from their accommodations without compensation.

Organised Crime

Under certain conditions, organised crime also leads to displacement.30 In some Latin American countries, such as Honduras and El Salvador, the number of violent crimes is so high, and the negative effects of gang crime so serious, that a substantial part of the population feels compelled to move.31 IDMC estimates that at least 432,000 people in the Northern Triangle of Central America were affected by this at the end of 2017.32 Often these are individuals or individual families, so the phenomenon is even less visible than other forms of displacement.33 This variant, too, usually affects poor population groups, which do not have the necessary resources to protect themselves from violent crimes, and it indicates that the state has not fulfilled its duty to protect its own citizens.

The Role of International Actors

Since internal displacement occurs predominantly in developing countries, the fact that wealthy states also actively contribute to the phenomenon is often overlooked. Some of them finance dubious infrastructure and agricultural projects, fuel local conflicts, or send rejected asylum seekers or temporarily vulnerable persons back to places where they become internally displaced.34 The legal framework of the global refugee regime also has a direct impact on internal displacement, as many countries apply the principle of the “internal flight alternative” in their asylum procedures: They only grant people access to international protection under the Geneva Convention if they can prove that they could not find safety elsewhere in their country of origin.35 In these instances, internal displacement is legally considered the preferred alternative to cross-border flight.36

Structural Drivers and Protracted Internal Displacement

When comparing the different scenarios in which internal displacement occurs, it becomes clear that – although the above-mentioned triggers are ultimately determinative for the relocation of individual persons – pre-existing economic, social, or political disadvantages have a major influence on which population groups are most affected. These structural drivers increase the risk of displacement in two ways. On the one hand, poor and marginalised population groups are more vulnerable to displacement for several reasons: Members of such groups often settle in areas that are threatened by natural disasters or riven by organised crime. Furthermore, they often lack the reserves to bridge periods of scarcity caused by climatic or economic factors. It also often happens that state authorities do not protect them from displacement by private actors.37 On the other hand, they find it particularly difficult to overcome disadvantages resulting from their displacement. They are therefore disproportionally affected by protracted displacement (see text box).

In contrast to temporary displacement, protracted internal displacement is not an inevitable consequence of conflicts or natural disasters, but – at least in part – the product of fundamental political failures and deficiencies. This weakens the previously introduced distinction between internal displacement that does involve and that which does not involve the participation of state actors. Since the primary responsibility for the protection of IDPs lies with the state authorities of their respective home country, protracted displacement indicates that the state has failed in this respect, regardless of the original trigger of the displacement. Therefore, the risk of protracted displacement is particularly high in countries characterised by social inequality, ethnic tensions, and weak institutions. Often, as in Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, there are several large waves of displacement over the course of decades, which, although they have different triggers in individual cases, can jointly be attributed to a “permanent crisis of statehood”.38 Structural discrimination in these cases manifests in the lack of state support to overcome the disadvantages suffered in the course of the original displacement. The extent of state support for IDPs often depends on how much political capital national authorities can draw from this commitment. People in geographically and politically remote parts of the country, as well as politically unpopular groups and ethnic minorities, often lose out. Besides state weakness and the political neglect of affected population groups, repression by authoritarian governments can also perpetuate internal displacement. For example, state actors sometimes prevent people who left their homes due to natural disasters from returning, so that short-term, disaster-induced displacement is transformed into longer-term displacement perpetuated by the state.39

|

Protracted Displacement The term “protracted displacement”, introduced at the end of the 2000s, has fundamentally changed the political debate on internal displacement. The determining criterion for describing a displacement as “protracted” is notits duration, but rather whether any progress towards durable solutions is discernible, or whether the situation is becoming engrained.a This perspective also changes the assessment of humanitarian aid operations in cases of displacement by drawing attention to the deficits of an understanding of protection that is limited to “care and maintenance”. This narrow understanding of protection can lead to scenarios whereby those affected become permanently dependent on aid programmes and transfer payments.b a IDMC, IDPs in Protracted Displacement: Is Local Integration a Solution? Report from the Second Expert Seminar on Protracted Internal Displacement, 19–20 January 2011 (Geneva, May 2011), 7. b Center on International Cooperation, Addressing Protracted Displacement: A Framework for Development-Humanitarian Cooperation (New York, NY, December 2015), 6f. |

|

Additional data requirements Total figures give a first impression of the extent of internal displacement. However, they have only limited practical use, since the support needs of those concerned vary according to the context. A more detailed assessment of the conditions in which IDPs live in the various countries and regions is needed in order to distribute the available resources sensibly and to develop appropriate recommendations for action. This is where a recent IDMC initiative comes in that assesses the severity of displacement in different countries and regions in eight issue areas:a (1) security, (2) income opportunities, (3) housing, (4) basic public services, (5) access to documents, (6) family reunification, (7) political participation, and (8) access to the legal system.b This new frame of reference offers helpful starting points for the work of development actors in particular. However, the planning and implementation of the appropriate assistance requires further information, ideally in the form of disaggregated data that reflect the socio-demographic structure of IDPs and their specific needs. This is time-consuming and costly, but it forms an important foundation for targeted programming. Since many affected governments are unwilling to deal with internal displacement, scientists are faced with a kind of chicken-and-egg problem when collecting data: Reliable data are necessary to make the problem visible and to bring it into the public domain. At the same time, however, the governments concerned would first have to acknowledge that there is internal displacement. As long as they deny this, they will not provide the financial and administrative resources necessary for data collection and analysis. a IDMC, Impact and Experience. Assessing Severity of Conflict Displacement. Methodological Paper (Geneva, February 2019). b These sub-sectors meet the criteria of the Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons developed by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) of the United Nations (see the section on “Political and Legal Regulatory Approaches” in this paper, p. 22). |

Case Studies: Ethiopia and Pakistan

Large-scale displacement not only leads to high personal costs, but also to structural changes. Typical consequences include increased urbanisation, a shift in traditional power relations, and an exacerbation of social inequalities. Ethiopia and Pakistan are useful case studies for illustrating these different trends, since both countries have been affected by different forms of internal displacement for decades and have experienced far-reaching economic, political, and social impacts.

Ethiopia’s history is marked by recurring waves of displacement. The politically motivated denial of internal displacement also has a long history. Both Haile Selassie’s regime and the subsequent Derg military regime in the 1970s and 1980s feared reputational damage as a result of large-scale displacement caused by mismanagement and famine. In the course of the economic upswing since the turn of the millennium, Ethiopia has embarked upon a number of large and prestigious infrastructure projects. In this context, the government resettled many citizens without taking into account the social costs of such measures. The routine denial of there having been expulsions – particularly those caused by conflict and development – was a permanent feature of Ethiopian politics until very recently. As a result, for a long time international actors were only able to provide very limited support to those affected.40 This changed when the new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, took office in May 2018. The Ethiopian government now acknowledges the existence of conflict-induced internal displacement, it seeks support from aid organisations, and it engages constructively in international discussions on improvements in this area.41

The political opening in Ethiopia under Ahmed coincided with a rapid increase in new displacements.

However, the political opening under Ahmed coincided with a rapid increase in new displacements. In addition to 296,000 displacements due to natural disasters such as droughts and floods, Ethiopia experienced 2,895,000 new conflict-induced displacements in 2018, the highest number world-wide.42 The causes were mostly social and ethnic tensions that had existed for a long time and were kept under control by the previous authoritarian government; in the context of the newly created political freedoms, these tensions have been increasingly unleashed in violent conflicts.43 Overcoming this problem is a monumental task for Ahmed’s government. The national Durable Solutions Initiative for IDPs, launched in December 2019, is a step in the right direction, so long as it respects the freedom of choice of those affected and does not push them to return prematurely.

Since Pakistan’s founding in 1947, migration and expulsion have shaped the country’s history. Between 2010 and 2015 alone, around 1.5 million people had to leave their homes due to natural disasters – mainly floods and earthquakes.44 Violent conflicts in the past have also regularly caused large waves of displacement. The FATA region (Federally Administered Tribal Areas), a semi-autonomous region in north-west Pakistan until its merger with the neighbouring province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2018, was particularly affected. It is considered to be a place of origin and retreat for terrorist militias, which the Pakistani army has repeatedly attempted to combat with major military offensives. During the Zarb-e-Azb offensive, which started in June 2014, more than 900,000 people were forced to leave their home regions within the first month.45

State authorities support different groups of Pakistani IDPs to very different degrees. Since 2007, assistance to people who have been forced to leave their homes because of natural disasters has been coordinated by a network of regional disaster management authorities and is relatively well-organised. But there is no institution that takes care of those who have been displaced by conflict. In recent years, IDPs from the FATA region in particular have suffered from this deficit. In addition, the Pakistani government, concerned for its reputation, was anxious to cover up the extent of the fighting and displacement in the region, and therefore did not launch a humanitarian appeal.46

Reinforcement of Existing Urbanisation Trends

Urbanisation is considered a megatrend of the 21st century.47 Displacement, both internal and cross-border, is also increasingly becoming an urban phenomenon.48 This puts a burden on the infrastructure of affected cities, poses security risks, and creates social challenges. In Pakistan – a country already marked by rapid urbanisation – many IDPs have moved to the cities in recent years due to family networks or in search of income opportunities.49 This is particularly true of Karachi, the economic centre of the country, as well as the provincial capital Peshawar, whose population almost doubled between 1998 and 2013, from 1.7 to 3.3 million.50 In both cities, the already inadequate education and health care systems were not prepared for the high level of immigration; the water and energy supplies are equally inadequate. This competition for scarce resources leads to resentment among the local population towards newcomers, thereby fuelling social tensions. Thus, the competition for housing is intensifying, and the poorest population groups are being pushed to the periphery of the cities. In addition, new security risks arise because the Taliban use Karachi as a place of retreat and to recruit new fighters. At the same time, IDPs from the FATA region are experiencing further disadvantages, as they are sometimes perceived as Taliban allies and are therefore subject to increased state controls. The consequences are restrictions on their freedom of movement and discrimination when looking for work.51

In Ethiopia, where current calculations show that 86.8 per cent of the population lives in rural areas, internal displacement and urbanisation are less strongly linked than in Pakistan. Nevertheless, IDPs constitute an above-average proportion of the urban population: 21 per cent of those affected live in cities or peri-urban areas, compared with 13.2 per cent of the total population.52 In both countries considered here, internal displacement contributes to slum development. In turn, the housing situation in slums often carries an increased risk of disaster-induced displacement.53

Increasing levels of urbanisation, however, not only bring disadvantages but also create opportunities. If IDPs are supported in their entrepreneurial endeavours, they too can make positive contributions. For example, they can strengthen trade relations within the country.54 Particularly in the case of protracted internal displacement, it is unlikely that displaced persons will return to rural areas. It is therefore important to recognise the long-term demographic changes resulting from internal displacement at an early stage and to take them into account in urban planning processes. This is the best means for meeting the challenges of displacement in urban areas.55 Support from international actors can be helpful here. It is beyond the competence of humanitarian actors to adapt complex urban systems to the demands of rapid immigration. The necessary expansion of public services and material infrastructure can only succeed in close coordination with the respective city administration. It is therefore usually a task for development actors.

Shifts in Established Power Relations

Civil wars often result in the expulsion of minorities, sometimes, as in the Bosnian War, with the explicit aim of ethnic segregation. However, internal displacement due to rampant, omnipresent violence or natural disasters also carries the risk, especially in multi-ethnic societies, that the power relations which have been balanced over years and decades may be called into question, thus fuelling conflict.56

The federal system of Ethiopia has been organised along ethnic lines since 1991. Six of the nine federal states that make up the country as a whole, namely Afar, Amhara, Harar, Oromia, Somali, and Tigray, are each dominated by a different ethnic group. The remaining three are more ethnically mixed. Even though the central government, which was clearly authoritarian until the change of government in 2018, has great power, this federal structure allows for a certain degree of self-government and cultural autonomy. However, the federal system by no means fully reflects the diversity of Ethiopia’s multi-ethnic society. Moreover, the political participation levels of the groups that dominate the individual states are not equal, since some of them participate in the central government while others do not. The system as a whole is fragile because, among other things, migration movements within the country disturb the coherence of ethnically dominated regions. Border disputes and land conflicts regularly lead to internal displacement in Ethiopia. In 2018 and 2019, for example, there were violent clashes both within Oromia and Harar, on the borders between Oromia and Somali, and between Amhara and Tigray, as a result of which many people were displaced.57 The origins of some of these conflicts lie in previous state resettlement programmes, during the implementation of which traditional land rights were ignored.58

Pakistan is also a federal state, but its political system is less strictly organised along ethnic lines compared to Ethiopia. Nevertheless, the displacement of population groups has brought about demographic changes in individual regions and thus has called existing power relations into question. This can be illustrated by the example of Karachi, Pakistan’s capital from the founding of the state in 1947 to 1959, and today the country’s leading economic metropolis and the capital of Sindh province. As a result of the violent riots that accompanied the partition of India after independence from the British Empire, many Muslim refugees (the Mohajirs) from India settled in Karachi. Decades later, the Pakistani military government under Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq mobilised this group to create a counterweight to the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), which had its stronghold in Sindh. This led to the founding of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) in the mid-1980s, a political party that initially fought for the rights of the Mohajirs and their descendants. The MQM proceeded to become an important opponent of the PPP in Karachi and in Sindh province.

Due to its economic attractiveness, Karachi also became the largest Pashtun city outside the traditional Pashtun settlement areas in the north-west. From 2007 onwards, the moderate Awami National Party (ANP) developed into the political mouthpiece of the Pashtun middle class in Karachi. The concern of the established parties about a further strengthening of the ANP resulted in prejudice against Pashtun IDPs seeking refuge in Karachi.59 Ultimately, however, the ANP did not succeed in becoming a decisive force in Karachi. One important reason for this was that their representatives were deliberately threatened by Taliban supporters in the early 2010s and became victims of attacks.60

Exacerbation of Societal Inequalities

Displacement not only brings about new human rights violations. Often, long-standing patterns of disadvantage and marginalisation are perpetuated and reinforced. In Pakistan, IDPs from the former FATA region are discriminated against, for example when looking for work.61 They are also being urged to return to areas that are no longer officially classified as conflict areas, but in which water and electricity supplies, as well as access to education and health, are still not guaranteed.62 However, there are other forms of structural disadvantage. For example, people who had lost their homes due to the major floods in 2010 had to present a machine-readable identity card in order to receive financial support. Yet, since most Pakistani women are not registered under their own names but only as family members of a male relative, it was particularly difficult for single or widowed women to access these support services.63 Another disadvantaged group of IDPs were agricultural workers, who were quasi-feudally dependent on landowners and also had to leave their homes because of the floods. Some of the poorest among them reportedly did not return to their homes, fearing that they themselves would have to pay for the costs of the crop failure, and thus fall into debt bondage.64

In Ethiopia, on the other hand, poor population groups are especially affected by government resettlement programmes. In the course of the modernisation and expansion of the capital, slum dwellers and the rural population from the immediate vicinity of Addis Ababa in particular are being resettled. Many of those affected lose access to sources of income.65 It also happens time and again that state resettlement programmes violate the rights of host communities. Pastoralists, that is, shepherds who practise extensive natural grazing, are particularly affected by this. Since their land rights are often not formally documented, the areas they use are considered potential settlement areas, and they are resettled without prior consultation.66

|

Advantages and disadvantages of registration IDPs are often considered “statistically invisible” because they live scattered within host communities or with relatives and are not easily discernible in everyday life. As a result, the full extent of the need for support sometimes goes unrecognised or is denied by state authorities. In order to provide targeted assistance to IDPs, they must generally register with local or national authorities. Apart from purely practical challenges – similar to those involved in the registration of cross-border refugees – an additional problem arises here: An official status as an IDP may have the effect of singling them out from other nationals not affected by displacement. This can have negative consequences. On the one hand, the “visibility” generated by official registration can be dangerous, especially for persecuted minorities, for example if it results in physical attacks or triggers targeted discrimination. On the other hand, there is a danger that state actors will use registration as a pretext for shifting the responsibility for the protection and care of the persons concerned to aid organisations and will no longer fulfil their obligations towards their own nationals. This issue demands a high degree of political caution and sensitivity from international actors. Not only should a responsible and data-protection-compliant approach to personal data be guaranteed. Above all, registration should never be an end in itself, but should be made dependent on whether it is beneficial or detrimental to the overall situation of IDPs. |

A recent concerning development under the leadership of Prime Minister Ahmed is the state-organised repatriation of people who have only recently fled violent conflicts in their home areas. Such repatriations to areas that are sometimes still unsafe are not carried out under physical duress. In some cases, however, they are a prerequisite for access to food aid and other support services. For this reason, those who are particularly dependent on support have no choice but to accept the risks of return.67

Durable solutions are only possible if disadvantages caused by displacement are eliminated.

The comparison of two very different country contexts – Ethiopia and Pakistan – illustrates the longer-term challenges arising from internal displacement. State actors who shy away from structural change often try to restore the status quo that existed before the displacement. Hence they press for a quick return of the affected people to their homes. If, however, the circumstances for a safe return are not assured, or if the persons concerned have other preferences, this approach perpetuates the disadvantage suffered in the context of the initial displacement. For durable solutions, it is essential that disadvantages caused by displacement are eliminated. It should not matter whether people settle where they are, return to their home towns, or settle elsewhere. Such solutions are challenging and require that the respective state shows a high degree of willingness as well as an ability to act – international actors can help to strengthen both. These efforts are based on the standards and regulatory approaches to internal displacement that have been developed over the past three decades.

Political and Legal Regulatory Approaches

In contrast to the global refugee regime that is enshrined in the Geneva Convention and institutionally consolidated by the existence of UNHCR, the rights of IDPs are secured neither institutionally nor under international law. Nevertheless, important legal advancements have been made in the last three decades that strengthen the rights of IDPs and identify possible solutions. In addition to the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, there are also points of reference at the regional level, in particular concerning the protection of IDPs and the provision of development-oriented support. At the national level, more and more legal protection instruments have also been created.

Internal Displacement on the International Agenda

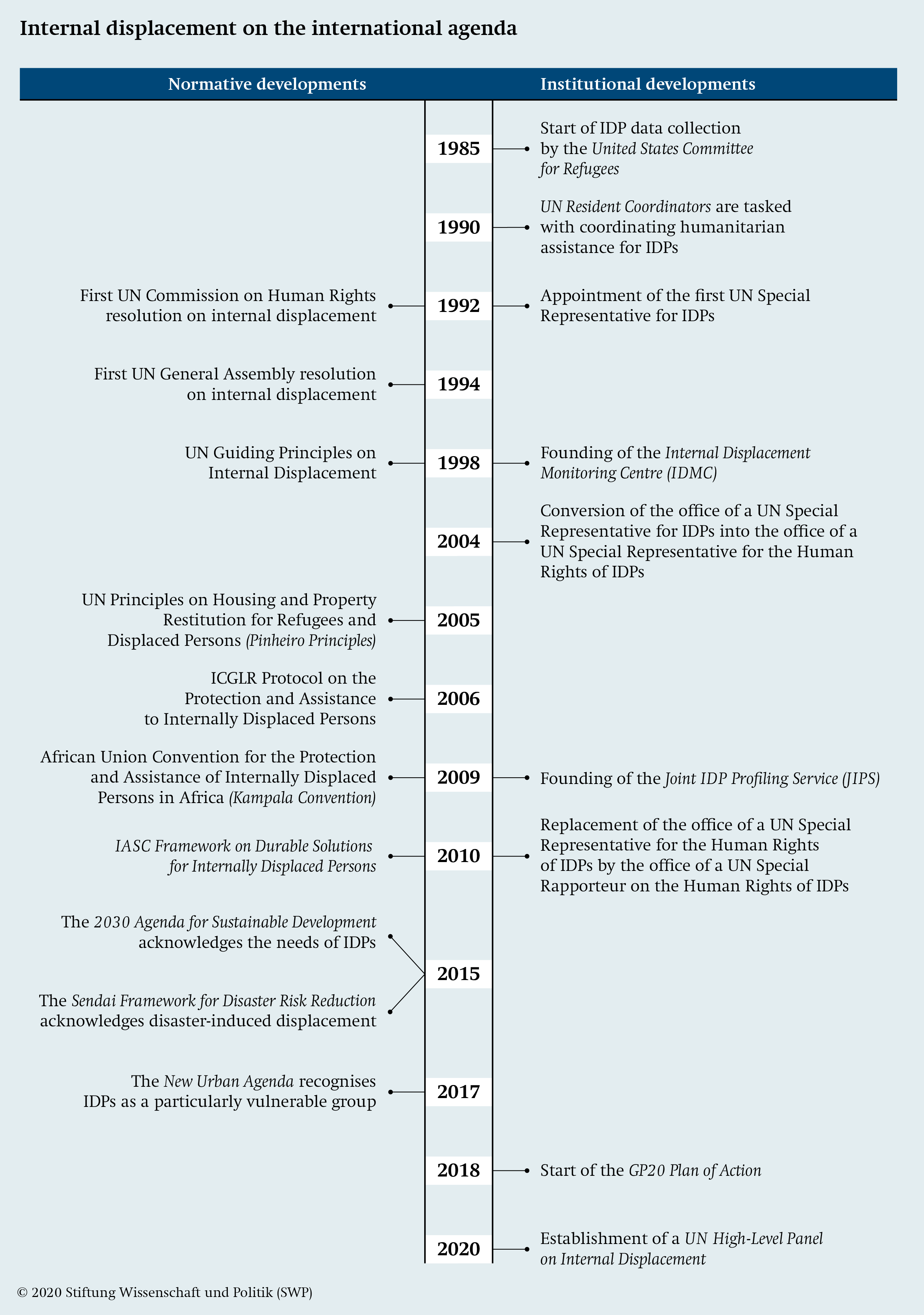

When assessing international developments pertaining to internal displacement over time, it is useful to distinguish between normative (binding and non-binding under international law), institutional, and discursive developments. The timeline in Figure 4 provides an overview of the first two areas.

International Legal Foundations

In 1992, the UN Commission on Human Rights adopted its first resolution on IDPs, in which it called, inter alia, for the appointment of a UN Special Representative for IDPs.68 The first incumbent was former Sudanese Foreign Minister Francis Deng. The urgency of his task was underlined by the upheavals of the Bosnian War. The existence of a large group of IDPs within a European state – and the concern of Western European states that these people might cross the border – brought the issue of internal displacement to the attention of the international community. Deng used this window of opportunity to strengthen the rights of IDPs. In 1998, he presented the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement to the UN Commission on Human Rights, which were developed under his aegis.

The Guiding Principles became the main point of reference for the protection of IDPs.

These Guiding Principles subsequently became the central reference point for the protection of IDPs under international law.69 They do not contain any new legal norms, but delineate how existing principles of international law and humanitarian law can be applied in the context of internal displacement. They are structured according to the different phases

of displacement. Section II is devoted to protection against displacement, Section III to protection during displacement, and Section V to return, resettlement, and reintegration. These are supplemented by general guidelines (Section I) and guidelines on humanitarian aid (Section IV). The primary responsibility of national authorities is a recurrent theme throughout the Guiding Principles.70

One of Deng’s main concerns was to overcome the contradictions between national sovereignty and an international responsibility to stand up for those in need of protection. Under the slogan “sovereignty as responsibility”, he advocated a sophisticated understanding of state sovereignty that does not hold legal self-determination to be absolute, but emphasises that it goes hand in hand with the responsibility of a state towards its own population.71 This understanding is taken up in the Guiding Principles, which stipulate that offers by international humanitarian organisations and other appropriate actors that can assist IDPs must not be arbitrarily rejected – “especially if the competent authorities are unable or unwilling to provide the necessary humanitarian assistance”.72 Deng thus created the concept of a state’s responsibility to protect, the non-fulfilment of which cannot be passively accepted, but rather must be compensated by the international community. He was thus one of the pioneers of the norm “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P), which was established at the UN level in the early 2000s, legitimising humanitarian interventions.73

With the publication of the Guiding Principles, the cornerstones of an international responsibility to protect IDPs were established. Over the next few years, further international and regional standards and legal instruments were developed. These include the Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons, also known as the Pinheiro Principles, adopted in 2005. They provide refugees and IDPs with the same legal security and access to housing and land as other citizens.74 In the African context, two agreements were concluded at the regional level that, to date, remain the only legally binding instruments of protection for IDPs under international law. The first is the Protocol on the Protection and Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), adopted in 2006, which makes the Guiding Principles binding for the 10 member states of the ICGLR. The second is the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) of 2009.

The Kampala Convention, in particular, points the way forward in several respects. First of all, it is the only legally binding instrument at the regional level to date that not only affirms the rights of IDPs but also spells out the resulting obligations for state actors. In addition, the Kampala Convention expands the possibilities for international engagement by authorising the African Union to intervene in member states if necessary and to help create durable solutions for IDPs. After Swaziland became the 15th African state to ratify the Kampala Convention, it entered into force in 2012. In the meantime, 31 states have acceded.75 A number of others have publicly expressed their willingness to do so soon.76

The end of internal displacement is not a one-off event, but a process.

At the UN level, it was Walter Kälin who promoted the implementation of the Guiding Principles in the national context. In 2004, he took over the UN office of Special Representative from Francis Deng, but with a new title that now entailed a focus on human rights (UN Special Representative for the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons).77 During Kälin’s term of office, the UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) developed a key document that was to shape discussions on internal displacement for years to come: The Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons for the first time defined the end of internal displacement not as a one-off event, but as a process, in the course of which the special needs of those affected are gradually reduced.78

Since the mid-2010s, some contradictory developments have taken place. On the one hand, internal displacement is increasingly being taken into account in important development and humanitarian processes. For example, the SDGs, which were adopted in 2015, list IDPs as a vulnerable group. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, adopted the same year, contains recommendations on how to prevent or manage disaster-induced displacement. The core commitments agreed at the World Humanitarian Summit 2016 include the ambitious goal of halving the number of IDPs by 2030.79 In addition, the New Urban Agenda of 2017 recognises the particular challenges faced by IDPs in urban areas.80

On the other hand, the topic is consistently omitted in key refugee and migration-related processes. Whereas in 2015 and 2016 cross-border migratory movements moved to the top of the international agenda in the context of large-scale immigration to Europe, the issue of internal displacement has not received the same attention, despite steadily increasing numbers.81 In the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants of 2016, IDPs are only mentioned in the introduction, and neither the Global Refugee Compact nor the Global Migration Compact, adopted at the UN level in December 2018, takes IDPs into account.82 This has serious consequences, for example in the distribution of funds earmarked for the implementation of the two compacts.

Institutional Developments and Responsibilities

From the beginning, institutional responsibilities for IDPs were fragmented. In the event of severe crises, they were distributed ad hoc to those humanitarian actors who were on the ground. The deficiencies of this system were known early on. As early as 1988, the UN General Assembly called for more effective coordination of humanitarian aid for IDPs. Since 1990, UN Resident Coordinators have taken on these institutional responsibilities, but significant shortcomings remain.83

In 1998, IDMC, financed by the Norwegian Refugee Council, was established. The work of this organisation improved the quality and availability of the data on IDPs and paved the way for a first stocktaking of the situation of IDPs world-wide. Two major UN publications in 2004 and 2005 came to the unanimous conclusion that the existing system could not ensure the protection of IDPs.84 The findings of these reports were an important driving force behind the UN humanitarian reform process completed in 2005, as well as the structural reforms within individual aid organisations.85 Since then, UNHCR, as head of the Global Protection Cluster, has had primary responsibility for the protection of conflict-induced IDPs and shares the leadership of the Camp Coordination and Camp Management cluster with the International Organization for Migration (IOM).86 Furthermore, OCHA and UNHCR set up organisational units specifically focussed on IDPs, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) developed, for the first time, an official position on the consideration of IDPs in its work. Within the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery was given responsibility for internal displacement. In addition, the Joint IDP Profiling Service (JIPS) was established in 2009. As a service provider, it offers to collect socio-demographic data on individual groups affected by internal displacement, thus facilitating targeted support. With the founding of the Global Program on Forced Displacement in the same year, displacement-related issues were put on the World Bank’s agenda, but without an explicit focus on internal displacement.

These institutional advances were thwarted by setbacks in other areas or were not sustainable. In 2010, the office of the UN Special Representative for the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons was replaced by that of a UN Special Rapporteur on the same issue. Although the change of mandate was presented to the outside world as a purely technical reform, it did in fact mean a downgrading of the office. Since then, it no longer entails official employment with the UN, but is fulfilled by a private individual without remuneration.87 The already poorly equipped position has only minimal travel funds. This complicates one of the role’s core tasks – official country visits – and makes the respective officeholders dependent on additional support from individual donor countries. At the same time, a number of humanitarian organisations, in particular OCHA, UNHCR, and the ICRC, reduced the size of their organisational units dealing with internal displacement or disbanded them altogether in the early 2010s, referencing the successful mainstreaming of the issue. Finally, UN actors have been urged by their donors to focus on their core mandates in the face of an increasing number of major crises and the resulting growing funding gaps, that is, in the case of UNHCR, on the protection of cross-border refugees.88

A few years later, the fact that IDPs were not mentioned in the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants prompted these same actors to reposition themselves on the issue. UNHCR, in particular, took a self-critical look at its previous role in the context of internal displacement during an operational review process in 2017. In the report that concluded this review, the organisation committed to giving greater priority to IDPs and formulated the goal of systematically raising money for cases of protracted internal displacement.89

In order to meet the complex challenges posed by internal displacement, much more flexible and longer-term financial resources are needed than are currently available. A reform of international financing structures would be in line with both the goals formulated in the “New Way of Working” and the recommendation on the Humanitarian–Development–Peace Nexus (the so-called Triple Nexus) adopted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee in February 2019.90 Due to existing organisational logics and competition between different actors, however, the level of implementation of these reform proposals has been slow. Nevertheless, promising progress has been made in some areas. New flexible financial instruments have been developed in recent years to support countries hosting large numbers of cross-border refugees. These are the Global Concessional Financing Facility and the Regional Sub-window for Refugees and Host Communities, which was introduced in the 18th budget period of the International Development Association (IDA).91 Comparable instruments for cases of short-term or protracted internal displacement, on the other hand, are lacking and are not planned for the coming IDA budget period.

To mark the 20th anniversary of the UN Guiding Principles on Internally Displaced Persons in 2018, UNHCR, OCHA, and the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons launched a new initiative, the GP20 Plan of Action.92 This three-year action plan follows a multi-stakeholder approach and has proved to be an important catalyst for intergovernmental learning.93 In parallel, IDMC and IOM established an informal dialogue format so that Geneva-based ambassadors of countries directly affected by internal displacement can exchange information. The representatives of the 18 countries involved so far have greatly appreciated the confidential framework and the depth of the discussions. Participation in the dialogue format can be seen as an indicator that the respective governments are open to dealing with the issue of internal displacement in a transparent and constructive manner. Furthermore, a common understanding of the problem is growing, which focusses on protracted internal displacement and the search for durable solutions.94

A further initiative was launched in the anniversary year of 2018. In a letter initiated by Norway and Switzerland, 37 states (including the 28 member states of the European Union, but also Afghanistan, Argentina, Georgia, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, and Zambia) called on the UN Secretary-General to establish a High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement in order to raise international awareness of the issue and develop new approaches.95 As the circle of support continued to grow, the UN Secretary-General decided to establish such a panel and entrusted UNHCR, IOM, and OCHA with the task of jointly designing and preparing it. The eight-member panel started its work in January 2020 and is expected to present a final report with recommendations after one year. It comprises government representatives, civil society, and private-sector actors, as well as representatives of international organisations, and it is supported by a secretariat in Geneva and a four-member advisory group. The members of the panel come from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Italy, Jordan, Colombia, Norway, Rwanda, and South Sudan. Most of these countries are strongly affected by internal displacement.96

This configuration gives reason to hope that the process will not be limited to navel-gazing (whereby only internal UN coordination problems are discussed), but instead address the pressing question of how affected states’ willingness to act can be strengthened. However, in the context of the corona pandemic, the field visits and consultations that were meant to inform the panel’s work are unlikely to happen, and can only partially be compensated through online meetings. Since no genuine development actor was involved in assembling the panel, it will also be a core task of the newly established secretariat to ensure the engagement of organisations such as UNDP and the World Bank in the ongoing process.

Discursive Change

When the United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants first collected figures on internal displacement in the mid-1980s, it was considered a purely humanitarian problem that primarily required better coordination of existing assistance.97 Francis Deng, the first UN Special Representative for IDPs, emphasised the individual rights of the persons concerned during his term of office, thus adding a human rights dimension to the discourse. Since 1998, this has also been reflected in the resolutions of the UN General Assembly dealing with internal displacement.98

A major achievement is that IDPs are mentioned as a vulnerable group in the Sustainable Development Goals.

In the years that followed, the implementation of the Guiding Principles in national law was a focal point of the international commitment to address the issue of internal displacement. The search for reasons for the continuing increase in numbers, despite progress in legislation, shifted attention to the prevalence of long-term displacement. Starting in 2009, numerous publications on the phenomenon appeared, which jointly established the term “protracted displacement” in the public discourse.99 This new focus has again found its way into the political discourse: In its resolution on internal displacement in 2014, the UN General Assembly took up the concept and added a development dimension to the humanitarian and human rights perspective enshrined in previous resolutions.100 The UN actors and non-governmental organisations concerned with internal displacement took up this change in perspective and advocated that internal displacement be taken into account in the context of international development policy processes. In this context, it is a major achievement that IDPs are mentioned as a vulnerable group in the SDGs.

At the same time, a consensus has emerged between OCHA, UNHCR, and IOM that immediate emergency care for displaced persons is not enough, but that the strategies and work programmes of humanitarian actors must from the outset address the entire “displacement continuum”, from prevention to durable solutions. In recent position papers, all three organisations acknowledge the need for early cooperation with a wide range of local actors, and for capacity-building and representation of IDPs, both at the national level and within specialised ministries and local governments. Overall, the repositioning is characterised by a more development-oriented view of the issue of internal displacement than was the case just a few years ago.101

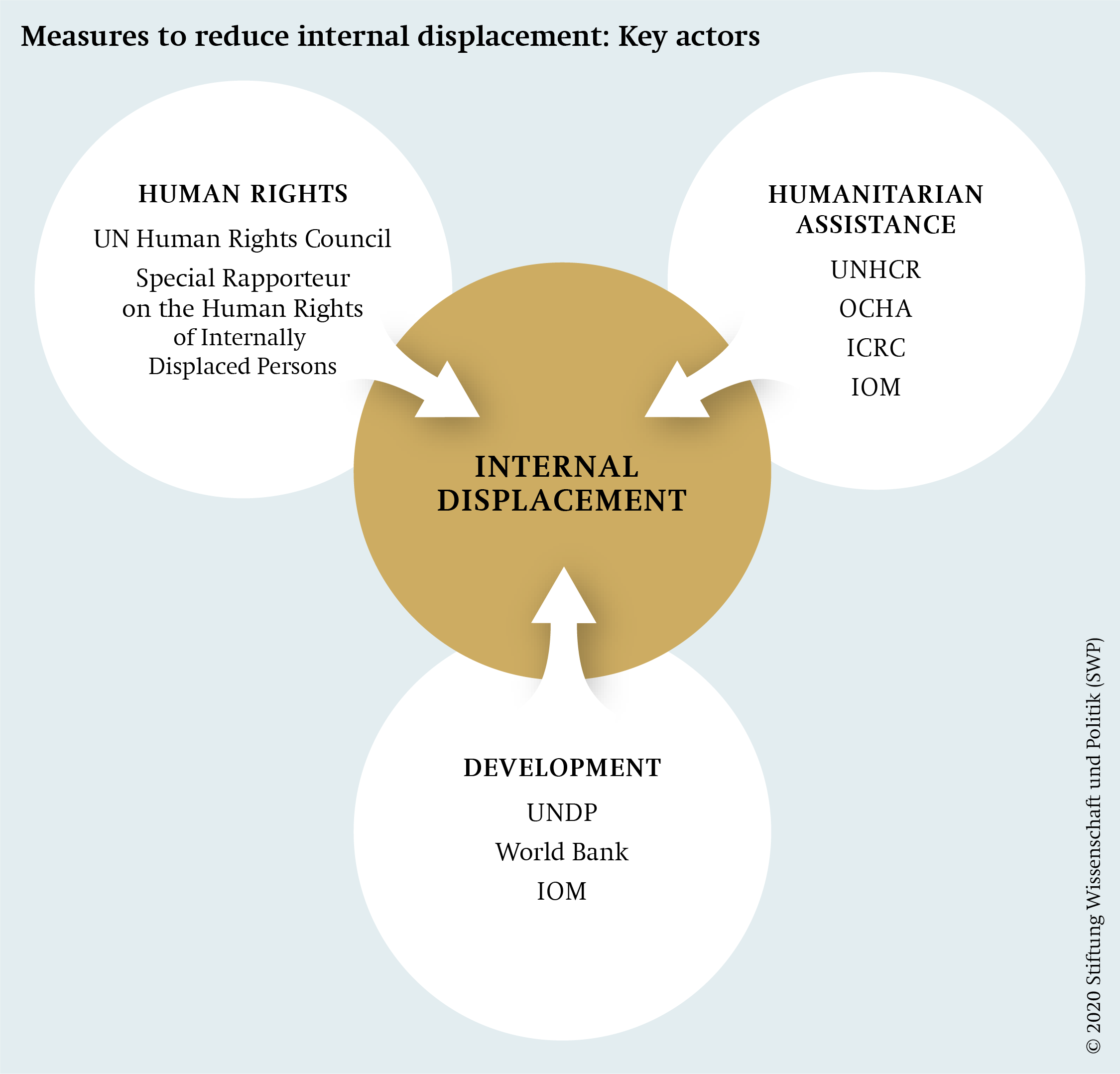

In the course of the last three decades, there has been a shift in the perception of, and the discourse on, internal displacement. As a result, it is no longer seen as a purely humanitarian problem, but instead as a multidimensional task that includes humanitarian, human rights, and development elements. This broadening of perspectives has been accompanied by the fact that more and more international actors are becoming conceptually or operationally involved in the field of internal displacement.

As they interact, these actors are forming a global regime of internal displacement that is slowly growing more solid. With the exception of IOM, which is active both in humanitarian and development policy, each actor involved is firmly rooted in one of the three dimensions. This results in an “empty middle” in institutional terms. The new IDP regime, whose norms and standards are currently being developed, lacks an actor who would serve as a central political advocate for IDPs. Experts on IDPs agree that such a position is necessary to achieve real improvements in protection and support for IDPs.102 It would therefore make sense to reintroduce the post of a Special Representative for IDPs who reports directly to the UN Secretary-General and deals with the issue in all its dimensions. In the spirit of the Triple Nexus, greater attention should also be paid to the peace-building dimension of internal displacement, and the relevant actors should be involved systematically and at an early stage in the debates on internal displacement.

National Protection Instruments

Since the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement are not binding under international law, they only take effect if they are integrated into national legal systems. The fact that this is increasingly the case speaks for their now consolidated and growing importance.103 The transposition of the Guiding Principles into national law can take different forms. It can either result in national legislation or be reflected in policy instruments and action plans based on the Guiding Principles.

Laws alone are not enough when resources are scarce or a country’s legal system is overloaded.

A legal basis is important to make state authorities accountable and to make the rights of IDPs enforceable. However, legislative procedures are usually cumbersome and lengthy, and laws alone are not sufficient when resources are lacking or when a country’s legal system is fundamentally overloaded or otherwise not functioning. Policy instruments such as ministerial decisions, ordinances, or action plans can be adopted more quickly, and this facilitates the application of general legal regulations in concrete cases of displacement. To date, the protection of IDPs has been enshrined in law in 13 countries, and relevant policy instruments exist in 35 countries.104 International actors’ ability to make a difference has been inconsistent: On the one hand, progressive national legal instruments have emerged under their guidance, while on the other hand, they have had little influence on the implementation of corresponding provisions.105 More important are often the positions of sub-national actors. In Afghanistan, for example, the implementation of the Afghan National Policy on Internal Displacement, adopted in 2013, is failing due to unresolved land conflicts because of resistance at the regional and local levels.106 In contrast, the efforts to establish a national protection instrument in Ethiopia were largely motivated by a previous initiative at the regional level.107

Given the difficulties in applying displacement-specific legal and policy instruments, other formats are worth exploring. Depending on the context, a sectoral approach that systematically takes into account the needs of IDPs in different policy areas may be a more effective form of protection. An example of this would be to include school access for IDP children in national education law.108 From a development perspective, mainstreaming the concerns of IDPs in national legislation is particularly promising if it makes existing structures more inclusive, instead of creating unsustainable parallel structures.109

The 31 African states that have so far acceded to the Kampala Convention have, by ratifying it, committed themselves to transposing the provisions contained therein into national law. So far, only one state has done so: In December 2018, the National Assembly of Niger passed a law to this effect. This was preceded by an extensive national consultation process, supported by UNHCR and the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, in which state actors as well as traditional and religious authorities participated.110 This example shows that international actors can help to give the Kampala Convention greater prominence in individual states, especially by supporting national administrations.

Persuasion at the regional level is more effective than economic sanctions or threatening military gestures.

The overall slow progress in ratifying and implementing the Convention indicates a lack of political will. Regional and (sub-)regional forums play an important role in driving the process forward, such as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, the Southern African Development Community, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Thematic exchanges among neighbouring countries, which often face similar challenges, can increase the willingness of national decision-makers to commit themselves to the protection of IDPs.111 In this area, the GP20 process has provided new impetus. Thus, Senegal and Cape Verde committed themselves to ratifying the Kampala Convention after a meeting of parliamentarians from ECOWAS countries with regional representatives of the GP20 process in March 2019.112 A quantitative study published in 2018 on the effectiveness of the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement supports the thesis that regional forums and actors play a central role. The results of the study show that persuasion at the regional level has a greater influence on the national implementation of the Guiding Principles than economic sanctions or threatening military gestures.113 This is an important lesson for future efforts to protect IDPs.

Perspectives and Scope for Action for International Engagement

Internal displacement is often a direct consequence of wars and violent conflicts. In these situations, the most pressing challenges are not initially displacement-specific. Instead, as is currently the case in Syria, the focus is on the much larger areas of conflict resolution, reconstruction, and reconciliation. Even in the event of devastating natural disasters, immediate emergency aid is the first priority for all those affected, whether or not they have been displaced. The circumstances are fundamentally different in the case of protracted displacement, that is, when disadvantages caused by displacement become permanent. In this case, the situation of those affected is not an inevitable consequence of acute triggers, but either politically intended, the result of political failures, or due to a lack of capacity on the part of the respective government.