Justice Reform as the Battleground for Genuine Democratic Transformation in Moldova

Insights for the Eastern Partnership

SWP Comment 2022/C 27, 11.04.2022, 8 Seitendoi:10.18449/2022C27

ForschungsgebieteThe euphoria felt by both domestic and foreign liberal audiences following the victory of a pro-reform party in Moldova is now receding. The new Moldovan leadership has stumbled in fulfilling its main electoral promise, namely to fight corruption by effectively reforming the justice system. There is a growing realisation that justice reform initiated and conducted with Western support over the last decade, and based on the implementation of existing best practices, might not be the most effective approach considering Moldova’s conditions. With corrupt courts and a public prosecutor office that is still connected to former kleptocrats, Moldova is a model weak state. A more suitable approach to justice reform would be to first establish prerequisites that would lead to the impartiality of the legal system before granting it political independence. This may also prove a more suitable model of justice reform for other Eastern Partnership countries undermined by strongmen and tycoons.

On 31 December 2021 the Rîșcani district court of Chișinău annulled President Maia Sandu’s revocation of her predecessor Igor Dodon’s appointment of Vladislav Clima as head of the Chișinău Court of Appeal. The district court ruled that its decision can be contested during a 30-day period at the Chișinău Court of Appeal, which is now once again led by Clima.

Sandu’s decree justified the move by pointing to a conflict of interest between Clima and two Supreme Court of Justice (SCJ) judges, as they were instrumental in nominating Clima. In fact, these two judges consequently blocked a SCJ decision to implement Sandu’s decree and actively delayed the SCJ’s reaction thereafter.

Vladislav Clima is a controversial figure. As a judge at the Chișinău Court of Appeal, Clima confirmed the decision of a lower level court to void the results of mayoral elections in the capital city of Chișinău in 2018, effectively overturning the victory of the opposition candidate. The ruling drew harsh criticism from the US and EU with both withdrawing their economic assistance to the Moldovan government, which was at that time controlled by the now fugitive tycoon Vladimir Plahotniuc. The Clima case illustrates the monumental challenge faced by Moldova’s new government as it struggles to reform a justice system appropriated by an organised “guild” of judges who exploit the law to preserve their own power and influence.

Political Inheritance of the Party of Action and Solidarity

By 2019 Moldova had suffered nearly a decade of oligarchic infighting for political power and control over lucrative businesses, an environment that led to the victory of business tycoon Vladimir Plahotniuc. In his pursuit for absolute power, he antagonised actors both at home and abroad, a reality that ultimately led him to flee the country due to pressure from the US – and indirectly Russia – to recognise the results of the 2019 parliamentary elections that his ruling Democratic Party lost and contested. A political struggle ensued between the Russia-funded Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM) – which aimed to take the reins of Plahotniuc’s now masterless kleptocracy – and the genuinely reform-driven Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS). In the end, Maia Sandu, the leader of PAS, won the presidential elections in November 2020, campaigning on an anti-corruption agenda. After a brutal legal and political battle with the desperately resistant Socialists and Plahotniuc-affiliated parliamentarians, Sandu managed to trigger snap parliamentary elections, which PAS overwhelmingly won in July 2021, earning 63 of 101 seats. This paved the way for her to set out to fulfil her promise of justice reform, as the previous parliament was controlled by the Socialists and their cronies who benefited from the status quo in the legal system and therefore resisted reform. However, now, several months after PAS gained the parliamentary majority, its appointed government is still trying to gain effective control over governmental institutions. It is hindered in doing so by a justice system permeated by corruption, ruled by clan practices and still connected to fugitive Moldovan tycoons that ruled the country up until recently.

The tug of war surrounding Clima’s appointment in which new authorities try to reform the justice system while courts obstruct these efforts is a vivid demonstration of the major challenges that the authorities face in their attempt to build a genuinely democratic state based on impartial rule of law. The problem runs deep. Between 1997 – when Moldova ratified the European Convention on Human Rights – and 2020, the European Court of Human Rights has delivered over 470 judgements on Moldovan cases, 90 per cent of which identify violations by Moldovan courts. Another instance highlighting the problem in Moldova’s justice system is the Russian “Laundromat ” case. Here, some $8 billion were laundered through Moldova using a scheme in which a local judge (fraudulently) ruled the existence of a debt which was to be paid by a Russian entity to a local account, consequently allowing money from Russia to be moved abroad. Moldovan prosecutors identified and accused some 16 judges involved in the fraud but 13 were later acquitted by Moldovan courts and five were reinstated to their posts at the recommendation of the Moldovan Supreme Court of Justice.

The corruption of Moldovan judges has been skilfully exploited by previous kleptocratic regimes, which turned a blind eye to their self-serving, unjust practices as long as they toed the party line. An informal contract existed between the two in which judges would be paid to deliver rulings that favoured the highest bidder and the kleptocrats in power. The courts’ services also involved granting legal backing for fraudulent appropriation of public property, seizure of competitors’ private businesses and persecution of political opposition.

If judges refused to comply with the Plahotniuc affiliates’ demands, the authorities would use prosecutors to pressure them. This was not difficult, given that many judges routinely engaged in corrupt practices, using their roles in the judicial system for personal gain. Gradually, a symbiosis emerged between the kleptocrats and groups of judges, some even being organised along family or kinship lines.

The Erosion of Effective Governance

Despite being in office for several months, PAS has been unable to secure de facto power even after obtaining de jure power by winning the 2021 elections. Although PAS defeated the kleptocrats politically, it has been confronted with the harsh realities of a corrupt justice system that operates independently, almost as a state within a state. The system of rents and informal institutional control that was built by the preceding kleptocratic regimes has proven robust and resistant to change. Paradoxically, previous legal reforms advocated and partially financed by the EU and US now protect the corrupt justice system from the new government’s attempts to cleanse it. These reforms, which aimed to insulate the justice system from political interference, were a sham under previous regimes as officials ignored the barriers and used a combination of coercion and co-optation to receive favourable rulings from judges. For the incumbent PAS government, however, the reform mechanisms have become a politically costly obstacle exploited by corrupt actors in the justice system to protect their interests. Thus, even though the PAS government appointed its ministers and other senior officials, the extent to which it has been able to take effective control over all governmental agencies and implement new policies is questionable.

This reality is observed in the relative continuity of many policies and approaches of the previous regimes. It is also seen in the increasing public discontent surrounding nominations of individuals linked to the previous regimes to important mid-level positions within public agencies. For instance, a former cabinet member of Plahotniuc’s Democratic Party was nominated to head a unit of the National Centre for Pre-hospital Emergency Care. This decision was ultimately annulled, but only against the backdrop of significant public outcry. Another move that drew extensive criticism was the PAS-controlled parliament’s appointment of Dorel Musteata to the SCJ. This became especially problematic as questions regarding the legality of his earnings emerged. Besides illuminating the difficulty that PAS is having in recruiting qualified individuals, these nominations reveal how powerful the influence of those connected to previous regimes still is.

Justice Reform: Obstacles and Options

The PAS government’s efforts to reform the justice system – its most prominent electoral promise – have thus been starkly scrutinised and criticised by the opposition and elements of civil society. To a large extent, this criticism is both biased and opportunistic. In the 101-seat parliament, PAS’s opposition consists of 6 seats held by the Șor Party, which is controlled by fugitive tycoon Ilan Șor, and 32 seats held by the electoral block comprising the PSRM and the Party of Communists. The PSRM is a peculiar force with strong dependency on the Russian government and links to Plahotniuc. These main opposition forces have strong connections with the old regime and would like to see PAS fail, and in doing so preserve their control over the kleptocratic mechanisms that still permeate state institutions. PAS’s failure would also offer new opportunities for other political forces, including the Party of Communists, in the next elections.

This environment has created an ongoing tug of war between PAS on the one hand and all other political forces – either parliamentary or extra-parliamentary – on the other. The opposition has also tried to involve Moldova’s development partners in constraining PAS, whether by claiming that PAS has nominated former corrupt judges and officials or that its legislative drafts do not conform to EU standards.

In the face of such challenges, the incumbent government has struggled to find any feasible solutions. Here, one answer could be to temporarily play the role of a “rational authoritarian”, invoking its strong legitimacy and authority given by popular mandate to forcefully intervene and temporarily adjust the legal framework in order to cleanse the justice system of corrupt schemes and individuals (including by vetting judges). Following this exercise, after the removal of all corrupt actors and practices, it could then revert back to the current legal framework designed to protect the legal system from political interference. The logic behind this approach rests on the assumption that a rational authoritarian can see the benefits in avoiding selective justice, as opposed to a kleptocratic authoritarian who flourishes on selective justice and the harvesting of public goods. Another solution – in which the incumbent does not have the full capacity to apply the coercive methods described above – would be to co-opt one of the players of the corrupt legal system and exploit them as a tool in purging the corruption by temporarily borrowing their powers; the government would then gradually need to replace the instrumentalised corrupt player as well. The PAS government tried the first method, but was quickly met with both domestic and foreign criticism claiming that PAS’s draft bills did not adhere to democratic standards. Internal actors were afraid that this approach would rewrite the kleptocratic rules of the game that they so enjoyed. Moldova’s development partners on the other hand were concerned that it could lead to an invariable slide towards authoritarianism. PAS’s questionable nominations seem to reveal they might be moving to the second method of co-optation. While the first approach risks tempting the government to set out on a path towards authoritarianism, the chances of this happening are largely mitigated in light of Moldova’s history of regular and largely competitive elections as well as the political culture of its voters. If the incumbent government embarks on a steady authoritarian path – as opposed to only using strong-hand practices for the duration of reform – PAS will very likely be voted out in the next elections. The risk of the second co-optation method is that the government is likely to become entangled in the corrupt schemes and agendas of the group that it co-opts. This could mean that the PAS government, or its associates, could acquire kleptocratic characteristics as well.

The strategy of co-optation is a typical element of transitional justice, whereby countries pursuing this approach simply lack a sufficient number of new and honest judges to replace the corrupt ones; or the governments do not have sufficient power to simply remove all corrupt players from the justice system at once. However, this method of co-optation requires a set of facilitating conditions in order to work. The authorities need to have the ability to be able to accept the costs of occasional coercion in case the co-opted player significantly departs from the logic of intended reforms. If the incumbent does not have the ability to effectively and promptly identify and sanction deviations from their plan, the result would probably be the monopolisation of the justice mechanisms under the single player who the government attempted to co-opt.

This risk is not negligible. As voiced by Moldovan civil society experts, the Moldovan legal system is very lenient towards corrupt judges; it is hesitant to sack them or to confiscate their ill-gotten gains. This represents a form of “professional solidarity”, as one observer puts it, and the public space is filled with anecdotes about corrupt judges and prosecutors. However, very little has been done by state institutions to investigate and sanction the violations of these actors and publicise their wrongdoings. Indeed, journalistic investigations are the only sources through which the public has been able to learn about the details of breaches of law perpetrated by actors within the justice system. Such investigations have revealed that a significant segment of judges in the superior courts, as well as prosecutors, tend to receive expensive donations and gifts from friends and families, including apartments, parcels of land and vehicles. It should not be surprising then that an International Republican Institute poll published in December 2021 revealed that the prosecutor’s office and the courts of justice were the public institutions viewed the least favourably: only 2 per cent of respondents had a “very positive” opinion of them, while 59 and 60 per cent expressed negative views of the respective institutions.

Given Moldovan judges’ tendency to protect each other, how does one break this vicious cycle and incentivise judges to respect the rule of law in an impartial manner? Answering this question is proving to be the incumbent government’s most difficult challenge. The state’s prosecution system was conceived, shaped and built to assist previous regimes in effectively collecting rents. Therefore, when PAS came to power, it found itself unable to ensure a functioning state that adhered to the rule of law. The courts operated like private entities, selling favourable rulings to the highest bidders; and they were helped by prosecutors, who were still informally controlled by the kleptocrats that had just been removed from government.

When PAS attempted to redress the problem by drafting amendments to the Law on the Public Prosecution Service, the PSRM-appointed Prosecutor General Alexandru Stoianoglo attacked the initiative, alleging that PAS misunderstood the principles of the rule of law. When he was consequently removed from office and put under investigation for passive corruption – among a number of other charges – media outlets with connections to Russia commenced an influence operation alleging that he was targeted because he was Gagauz – an ethnic minority in Moldova. These messages were also marketed to Moldova’s development partners via local embassies, particularly those of the US and EU, in the attempt to have them pressure the PAS administration. In short, kleptocratic actors who were losing control over the justice system attempted to falsely invoke democratic principles to manipulate Western officials into protecting the status quo.

In an act that further revealed the dysfunctionality of the public prosecution institution, Stoianoglo, together with the President of the Superior Council of Prosecutors, requested the opinion of the Venice Commission on PAS’s amendments to the Law on the Public Prosecution Service, including its mechanism to assess the Prosecutor General’s performance. The Venice Commission is the Council of Europe’s advisory body on constitutional matters, providing legal advice to member-states and promoting human rights and rule of law. In this letter, the two authors falsely alleged that the Law was amended in order to remove Stoianoglo due to his conflict with the new parliamentary majority. In its response, the Venice Commission recommended that the power to assess and dismiss the Prosecutor General remain exclusively with the Superior Council of Prosecutors. The Commission generally seemed to have accepted Stoianoglo’s story, failing to thoroughly investigate the case and differentiate between a politically motivated dismissal and an attempt to break fugitive tycoons’ power over the public prosecutorial system. The Venice Commission recommendations were based on the implicit assumption that the public prosecutor’s office was independent and effective in fulfilling its duties to investigate, litigate and resolve criminal charges with due regard for fairness and accuracy. This, however, was not the case. To be fair, it would have been difficult for the Venice Commission to justify an exceptional departure from the gold-standard on rule of law as it functions in the West. However, the Moldovan legal system is at a stage not unlike that seen by many Western countries before they built effective democratic institutions; they too were once weak states dominated by private interests. With this in mind, it is inappropriate and misguided to blindly project the West’s modern legal practices onto the feudalistic legal system that Moldova inherited from previous regimes.

![]() The Logic of Justice Reform

The Logic of Justice Reform

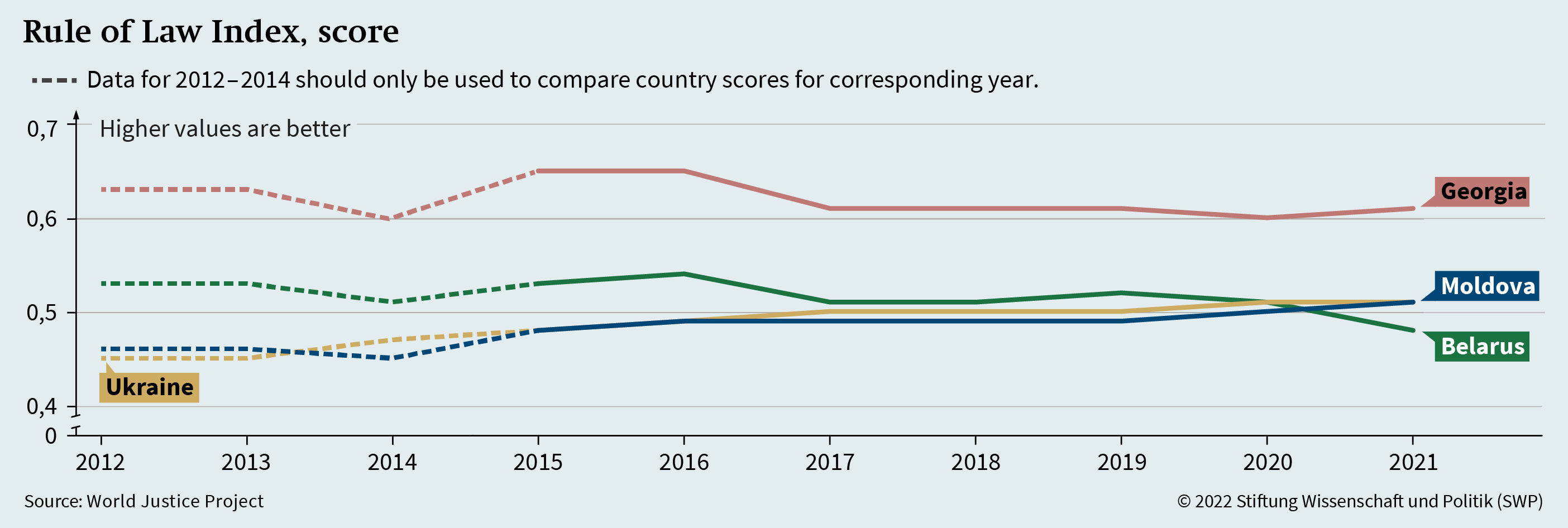

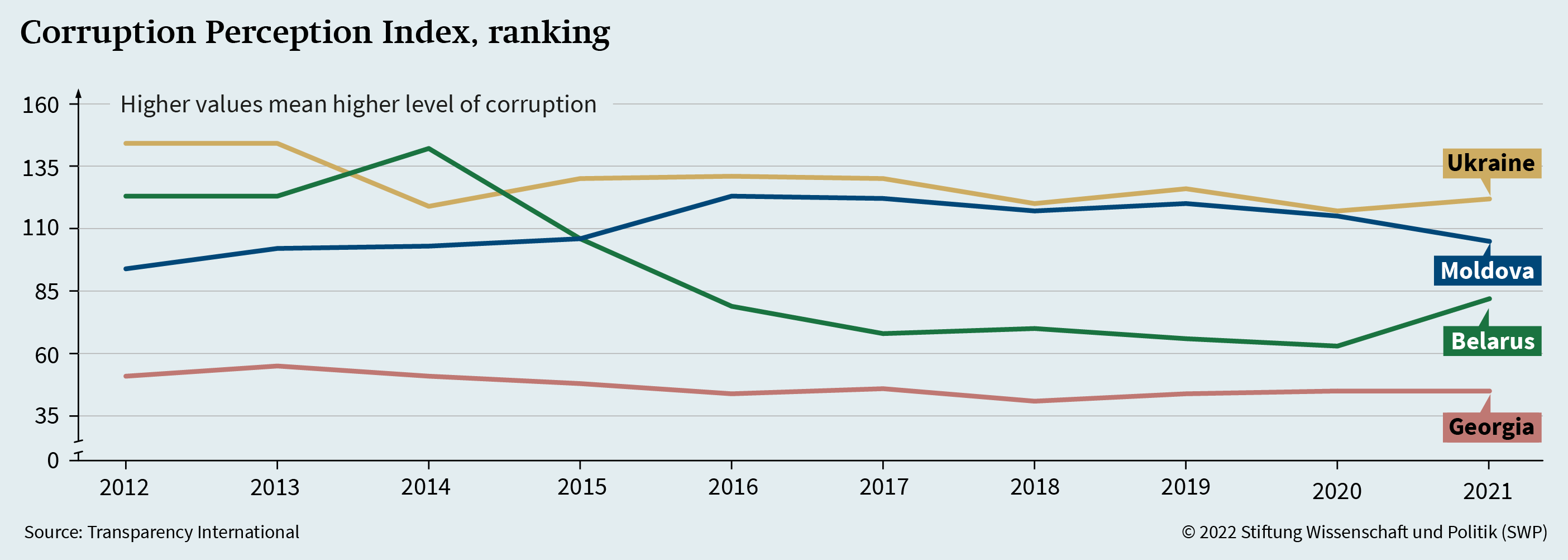

The questionable effects of past legal reform efforts conducted with support of Western organisations is not unique to Moldova. As seen in the first graph, despite years of reform between 2012 and 2021, the rule of law situation has not dramatically changed in Georgia, Moldova or Ukraine (Armenia and Azerbaijan were not included in the dataset). To the contrary, continuity or inconsequential changes to the rule of law are observed. Comparing and contrasting these changes with data from the corruption perception index graph, we can see that small positive changes to rule of law may even correlate with increased corruption in the case of Moldova. It almost seems as if the dynamics behind these two processes have – over the years – been drawn towards a specific and set value by some powerful attractor, suggesting the insignificant impact of reforms driving the rule of law and corruption processes.

The dynamics driving the changes to the rule of law in Ukraine and Moldova, on one hand, and the dynamics driving the changes to the rule of law in Belarus, on the other, seem to show a high degree of similarity. This suggests that reforms in Moldova and Ukraine produced an impact similar to the situation seen in Belarus, despite the latter’s lack of such reforms, thus underlying their failure. Here, despite not implementing Western-supported rule of law reforms, Belarus displays better results in terms of its placement on the corruption perception index when compared to Moldova and Ukraine, and a far superior improvement compared to Georgia. This quantitative evidence lends credence to the rational authoritarian logic explored earlier.

Western interventions for justice reform typically aim to promote the independence and impartiality of relevant justice actors and processes. Reform efforts advanced and funded by Western actors focus, as a rule, on promoting the independence of courts and prosecutor offices, aiming to insulate them from political interference. This approach implies that by doing so one can also achieve impartiality of the courts, which is starkly contradicted by the case of Moldova. Another implicit assumption is that generally, the legal system functions poorly because ruling elites and affiliated political actors attempt to influence legal processes. Yet another assumption is that courts and prosecutor offices will become impartial by default when they are protected from political pressure. In practice, Western development partners’ approaches towards justice reform in Moldova and the region prioritise judicial independence over impartiality, because the two are not necessarily interconnected. Thus, the Western model of an “independent judiciary” assumes that the judiciary itself is void of self-interest, a questionable idea indeed – especially in view of the situation in Moldova.

It makes sense to establish mechanisms that protect the justice system from political interference in strong states; but what about in countries with weak state institutions like Moldova? In such weak states – that are undermined by powerful private interests such as tycoons – political insulation of courts makes said courts even more vulnerable to the influence of the private actors. This is because, when tycoons start to yearn for political control, they then clash with the state and the political forces in power. When the state is weak, private interests can then acquire gradual control over and/or undermine select state institutions, including the courts. As these private interests take over the state, as occurred in Moldova under Plahotniuc and the short tenure of Dodon in 2019–2020, judicial reforms promoting courts’ independence are largely useless. At such points, the courts and prosecutors are not independent from private interests; and the state – being undermined by kleptocrats – is unable to take measures to counter these private interests and their corrupt actors in the justice system.

Here, when the state is free from the influence of tycoons, even in authoritarian contexts, it is still able to enforce the law in a non-selective way – albeit predominantly in the economic and social dimensions, and less so in the political one. However, regardless of how unorthodox it may sound, such an environment is a suitable foundation from which to begin genuine democratic reform and consolidation of the rule of law. This is because effective democracy starts with effective economic rights, which are enabled through the non-selective application of law, in turn leading to the evolution of effective political rights.

Outlook and Policy Insights

The new government in Moldova is facing major challenges in its planned reforms and in its ability to effectively govern the country. It represents an extreme case among the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) states, but extreme cases are often the most illustrative and illuminating. The PAS government is unable to acquire full and effective control over state institutions and processes as it is obstructed by a judicial system that sells justice to the highest bidder and a public prosecutorial system that is still under considerable informal control of recently removed kleptocratic forces. The existing legal framework, which is formally in line with European best practices and standards, serves as an obstacle to any government’s efforts to fix the problem. Moreover, the corrupt justice system is skilfully exploiting Moldova’s Western development partners by playing to their liberal ideals and claiming that rule of law in the country is in danger. It instigates them to exert pressure on the new parliamentary majority and, consequently, to obstruct its legislative actions and ability to effectively govern.

This exposes the ugly truth that corrupt and kleptocratic forces in Moldova still control the state, albeit informally. The case of Moldova emphasises the primacy of the judicial sector and related reforms in achieving effective democratic development and good governance. Based on the discussed rationales, a better understanding of Moldova’s case would be useful in assessing justice reform failures in other EaP countries. The Moldovan state is weak; exploited by private interest groups to collect rents. Its corrupt justice system is protected from political intervention, thus becoming a “state within the state”. The insulation of the justice system from political influence is an obstacle to governments that respect the rule of law, but it did not prevent previous authoritarian regimes from interfering with the courts and other actors of the justice system. At the same time, research indicates that some authoritarian regimes may even help to reduce the partiality of the court system in the economic and social realms.

In supporting rule of law reforms in EaP states, the EU should carefully consider and identify the core problems in each target country, adjusting the logic, pace and intervention behind reform assistance in order to understand and address the underlying mechanisms perpetuating the problems. It should not automatically apply its own model in EaP countries, but should instead focus on creating the conditions required for EaP states to gradually move from their current circumstances to the ideal model promoted by the EU. This reflects a “social engineering” approach that differs from the pre-packaged laundry list “standard model”. In Moldova’s case, this specifically means that instead of prioritising an independent justice system free from political influence, EU assistance should first work to build and strengthen the impartiality of the justice system. The two qualities are connected, but as the Moldovan case shows, they can also exist as independent conditions. Achieving the condition of impartiality would require the establishment of mechanisms that identify selective justice and then both effectively and promptly sanction it. Combining the rational authoritarian approach with selective co-optation would likely be the most effective solution. However, EU support for this would be necessary as the PAS government would otherwise suffer certain political costs. The EU is also a proper partner for PAS in this endeavour given its strong reputation and moral standing in the minds of the majority of Moldovan citizens. It should rely on its experience with legal reform assistance in Albania and other hybrid legal reform initiatives. In doing so it could consider assisting the Moldovan government in setting up an ad-hoc anti-corruption tribunal consisting of both national and international judges to investigate and sanction corruption within the legal system and with respect to high profile political cases. The suggested reforms should employ the logic of transitional justice, tailored to the weak state conditions of Moldova. They would need to keep in mind that transitional justice requires a balance between liberal commitments and political precautions. The reforms may be considered achieved when liberal norms are respected to the extent necessary for, and consistent with, the consolidation of liberal democratic institutions. This is important to consider, given that the law and its application is largely a dynamic condensation of power relations, and not just a rationalised technique for the ordering of social relations.

Dr Dumitru Minzarari is an Associate in the Eastern Europe and Eurasia Research Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2022

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

doi: 10.18449/2022C27