Given the strong economic interdependencies between the United States (US) and Europe as well as the shared commitment to safeguard civil liberties online and combat disinformation and unfair market practices, European Union (EU) cooperation with the US on digital markets is crucial. Thus, the EU-initiated transatlantic Trade and Technology Council (TTC) was established to navigate European and American understandings of “digital sovereignty” and the resulting market regulations. The first TTC meeting took place in September 2021 and demonstrated both a shared commitment to building an alliance on “democratic technology” and diverging ideas on how to best regulate the digital market and its biggest players. As the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed vulnerabilities of international supply chains and accelerated digitalisation, European policymakers are well-advised to continue pursuing their digital foreign policy strategy of advancing digital sovereignty by leveraging the “Brussels effect”, which also fosters the further integration of EU digital policy and contributes to the deepening of the transatlantic digital market.

Since 2015, the EU has found significant success in externalising its norms and principles in the digital policy arena, even prompting Anu Bradford to subtitle her 2020 book on the Brussels effect “How the European Union rules the world”. The Brussels effect is based on the idea that disputes arising from different interpretations by nations of key norms can be efficiently addressed by regulating private actors of the digital market. This is done so that they design their terms of service in compliance with internal market standards and even lobby foreign governments to adopt legislation convergent with EU law in order to increase legal certainty. The EU’s regulatory power in digital foreign policy is derived from its economic power, as evidenced by the fact that non-European digital technology companies – mainly headquartered in the US, but also in China – adjust their terms of services so that access to the European internal market is secured. A great example of the Brussels effect is the 2021 EU Cloud Code of Conduct (CCoC), which outlines detailed requirements for cloud service providers to protect personal data in accordance with article 28 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This code is a global first and a highly efficient regulatory framework that ensures compliance without being legally binding. However, a permission to operate cloud services within the internal market is only granted to companies that comply with the code, and so far, companies such as Alibaba Cloud, Google Cloud, IBM, and Microsoft have implemented data protection provisions in accordance with the CCoC. This demonstrates an efficient multi-stakeholder regulation of international service providers, as the European Commission developed the code in cooperation with private companies. Furthermore, the effort of formulating and implementing the CCoC is indicative of the process of European re-sovereignisation, which gained momentum with the necessity to govern the complex and transnational digital economy of the 21st century. Europe’s norms-based digital foreign policy has not only advanced its external sovereignty, but also its internal sovereignty, and it has intensified calls for deepening European integration as well.

EU Sovereignty in the Digital Age

The European Commission has declared the years 2020–2030 Europe’s “digital decade”, and a key challenge in this period is securing European “technological sovereignty” and digital sovereignty. These terms were first used by industry representatives who cautioned that industrialised European nations were dependent on the availability, integrity, and controllability of current and emerging technologies, both for civilian and safety purposes, and that Europe was lacking production capacities and R&D investments – which threatened technological sovereignty. Given that many concerns regarding the vulnerability of critical technological infrastructure are often also discussed as cybersecurity issues, the term “digital sovereignty” has emerged and is sometimes used interchangeably with “technological sovereignty”. Such discussions of the various dimensions of sovereignty demonstrate that the concept of sovereignty has become even more complex and is nowadays better understood as a process, not a status quo. In other words, sovereignty no longer merely refers to a legally defined status – instead, it needs to be understood in the context of EU actors’ moderating capacity of legitimising their positions through transparent, internal opinion-forming processes and exercising them effectively internationally in multi-stakeholder bodies and institutions such as the TTC.

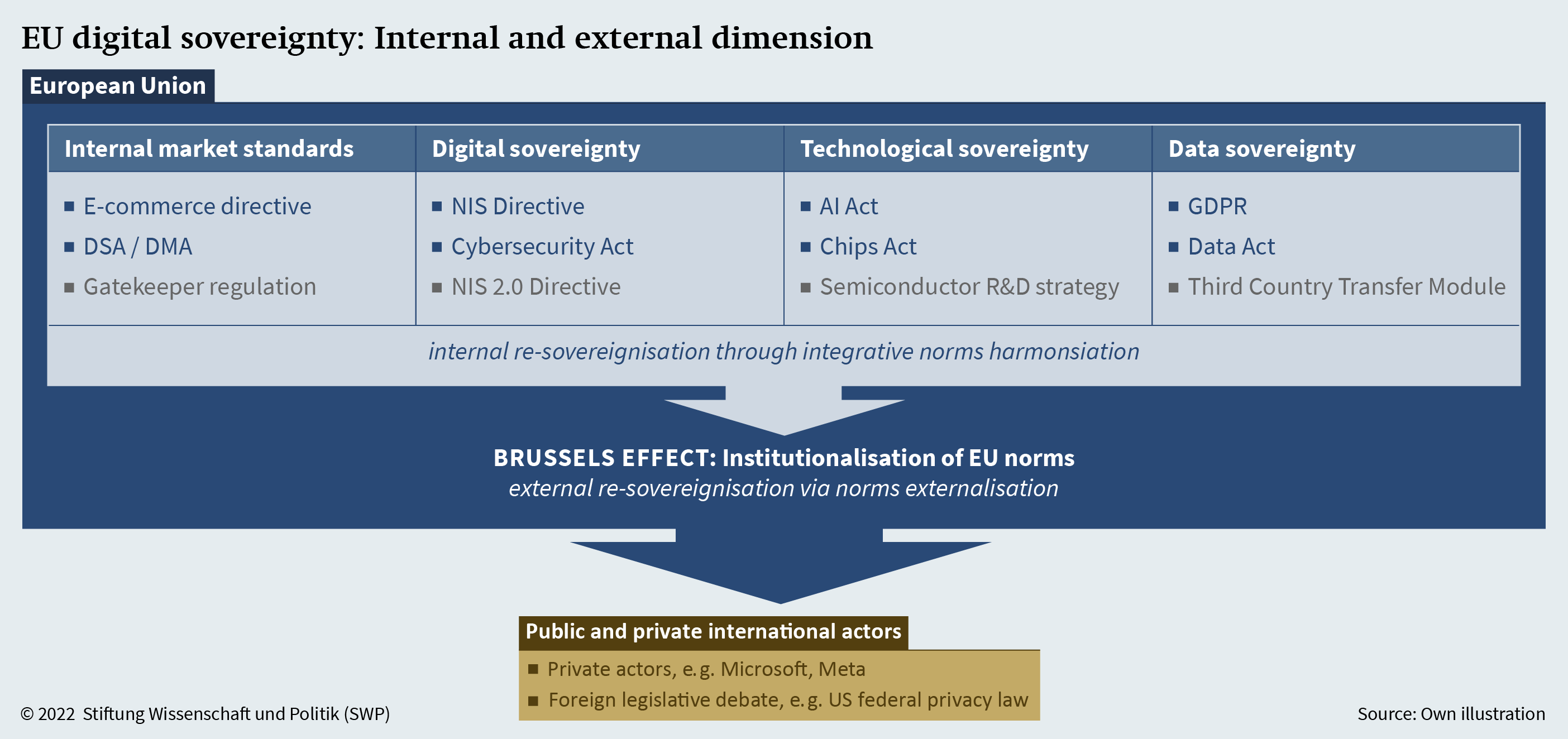

Consequentially, European technological and digital sovereignty have an internal and external dimension and emphasise that the key tool for European re-sovereignisation is Europe’s regulatory power based on its norms and values. Internally, the EU can offer guidance on transnational and complex issues such as liability in the platform economy or data protection on social media platforms; externally, the EU can institutionalise its core values and norms by setting the standards required for access to the internal market. In order to establish a framework that is reflective of ethical considerations and protects consumer rights while enabling fair market competition, company growth, and innovation, the EU – represented by the European Commission and the Council of Ministers – needs to facilitate cooperation between corporations, interest groups, and public bodies in complex and transnational issues such as interoperability and liability. Thus, an appropriate understanding of European sovereignty in the digital age encompasses both the internal and external dimensions of European action, and that refers equally to the member state, European, and international levels of digital policies. In other words, sovereignty today is more appropriately understood as a multi-level political practice.

EU Digital Policy

As part of Europe’s digital decade, the European Commission initiated a variety of acts and directives with a special focus on digital sovereignty and both of its dimensions: externalising European norms by regulating access to the internal market, and deepening European integration by providing guidance on digital challenges. Although regulatory competencies for current and emerging digital technologies rest with member states, EU digital policy has advanced positive and negative European integration (see SWP Comment 43/2015) and non-binding documents, such as the CCoC, and demonstrates successful leverage of European regulatory power in digital foreign policy affairs. The following brief overview of the central pillars of the EU digital strategy and relevant tools illustrates two key observations: The EU seeks to safeguard its digital sovereignty by externalising its fundamental values, such as core principles of the internal market (mutual recognition, direct-effect, non-discrimination, etc.), but its new rules and regulations primarily apply to foreign companies, especially in the US and Asia (specifically South Korea and China), which can lead to disputes.

A common EU digital foreign policy first started to take shape with the 2016 EU Network and Information Security directive (NIS Directive), which consists of three parts – national capabilities, cross-border collaboration, and national supervision of critical sectors – and first set international standards in the cyber realm by regulating access to the European market. Since 2021, the NIS 2.0 Directive and the mandate of the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy to enter into interinstitutional negotiations has further advanced the debate surrounding framework guidelines for European cybersecurity and demonstrated potential for harmonised EU-wide cyber regulation.

In 2019, the European Parliament adopted the EU Cybersecurity Act, which established a cybersecurity certification framework for information and telecommunication products and services that companies want to offer on the European market, overseen by the EU Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). Additionally, the Commission issued a recommendation for ensuring the cybersecurity of 5G networks in March 2019 and presented a “toolbox” on secure 5G networks in January 2020. The toolbox includes strict access controls before allowing a telecommunications company to contribute to the establishment and operation of national 5G networks. Especially in the US, where the Federal Communications Commission has identified and listed five companies (all from China) whose equipment and services are deemed an unacceptable national security risk, critics remarked that the toolbox was not strict enough. Meanwhile, some European governments and companies have expressed concerns for the advancement of their digital connectivity if global market leaders such as China’s Huawei are excluded from the internal market, which again illustrates the importance of agreeing on norms and standards with the US, as American companies can provide feasible alternatives and help advance European connectivity.

The 2021 Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) constitutes the first regulatory framework for such technologies worldwide, as it introduces a risk-assessment framework that is designed to regulate access to the European market based on the risk category evaluation of a company’s AI technology products. European and international companies have welcomed the introduction of a regulatory framework in a hitherto largely unregulated field, but they have expressed concerns that the act could prove to be innovation-inhibiting, as companies do not yet know how strictly the evaluation criteria will be interpreted and could thus lose the incentive to invest in new AI applications that they might never be able to commercialise, as interoperability with European systems is uncertain.

The European e-commerce directive was over 20 years old when the Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA) were introduced, which address issues that have arisen with the emergence of new products and service providers on the digital market. Still, the e-commerce directive remains the cornerstone of European digital strategy and digital foreign policy tools of regulating market access and institutionalising European norms. The e‑commerce directive sets standards for transparency requirements for service providers and liability along the business chain, to include intermediary service providers, and general rules for commercial communications. As the digital economy further diversified and personal data of private citizens themselves became an economic good, the EU updated its rules to ensure the data sovereignty of its citizens and companies.

The DSA introduced new rules in the issue areas of transparency, with specific information obligations on the storage and commercialisation of user data, handling hate speech and participation bans, and reporting users who are found to share illegal content. The DMA is designed to establish a level playing field for enterprises in the digital age and to enable innovation and growth. It is tailored to regulate “gatekeepers”, which are defined as “large, systemic online platforms”. Examples of gatekeepers (although no companies have been designated as gatekeeper so far) would be Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) depending on these gatekeepers shall be protected by the DMA, as gatekeepers can no longer utilise their power as platform providers to advertise their goods and services more prominently, or prevent users from uninstalling or disabling specific software if they wish to do so. Furthermore, gatekeepers are now required to allow commercial users access to data they generate while using their platforms, and to allow third parties to inter-operate with their services. The data sovereignty of European citizens is also protected by the recently adopted Data Act, which clarifies under which conditions private data can be commercialised.

The 2022 EU Chips Act is designed to integrate national efforts into a coherent European semiconductor research strategy and to facilitate collective action for (re-) building production capacities in order to reverse the trend of outsourcing semiconductor production – Europe once had the highest production output but now only 10 per cent of the global chips industry’s market shares are there. Chips (also known as semiconductors) are critical components of digital technologies manufacturing, both in the civilian and military realms – and currently so high in demand that there is a global shortage. While American companies such as market leader Qualcomm design the chips, they are manufactured mostly in Taiwan – one single Taiwanese company produces 92 per cent of the global chip supply of the most advanced chip type, creating a highly vulnerable supply chain bottleneck.

This outlined European digital foreign policy has already greatly advanced the data sovereignty of European citizens and levelled the playing field of the digital market while also increasing protection against cybersecurity threats, thus significantly contributing towards securing European digital sovereignty. However, Europe cannot achieve digital sovereignty alone – as of now, it lacks production capacities, big digital technology companies, and to some extent also the relevant digital infrastructure. Therefore, transatlantic cooperation and action are necessary for securing the digital sovereignty and geopolitical position of the EU and to further ensure fair market competition and the safeguarding of the civil liberties of its citizens – and the same applies to the US. For instance, the US and the EU account for 21 per cent of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity, but for 43 per cent of the global consumption of digital devices, revealing a potentially dangerous dependency on Chinese manufacturers.

Institutionalisation of the TTC

All recent conflicts in matters of trade and tariffs aside, the EU and the US still share an unwavering commitment to democratic values and fair market competition, which distinguishes them from Chinese competitors in digital services and technology production. Therefore, the European Commission proposed a Trade and Technology Council (TTC) in mid-2020 to find common ground on trade and technology standards after a contentious relationship and disagreements with the US on economic policies during most of the Trump Administration. While this suggestion received only little attention then, the Biden Administration showed greater interest in cooperating with the EU and exploring the idea of an alliance on democratic technology, and the TTC held its inaugural meeting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on 29 September 2021. Ten working groups of the TTC have been established, and a second meeting is planned for the spring of 2022.

The overarching European goal being pursued via the TTC is “values-based digital transformation”. The European approach in proposing and participating in the TTC clearly bears the hallmarks of the EU digital foreign policy strategy based on the Brussels effect. For instance, its pioneering act on AI regulation, which is designed to prevent the exploitation of this technology for illicit and unethical purposes, first sparked a debate on its purported innovation-inhibiting effect, and then resulted in the establishment of a TTC working group seeking to specify the rather broad legal speech of the act. International companies might express a hesitancy to invest in AI R&D when interoperability with European systems is uncertain, as a lack of compliance with European standards means exclusion from the internal market, and thus the loss of an important opportunity to commercialise. However, a realistic take on this issue also shows that such companies can hardly sustain their growth if the European market is inaccessible. Therefore, they have to seek cooperation with the EU and comply with requirements that ensure the overarching goal of protecting European citizens’ rights.

A case in which the Brussels effect even extends beyond the regulation of private actors and shapes foreign legislative debates is the US legislative debate on a federal privacy law. This debate gained momentum after a joint call for a federal privacy law similar to the GDPR by key players such as Apple, Alphabet, Meta, and Microsoft. The involvement of dominant tech companies in this process highlights the power of the Brussels effect, as even strong market dominators such as Meta need to reconsider their terms of service and data commercialisation business model if they want to retain access of the internal market. This is evidenced by the U-turn performed by its executive board in 2020, when key executives initially threatened to pull platforms such as Facebook and Instagram from the European market in response to the Schrems II ruling but quickly backtracked, as this tactic did not influence the European position as desired. Twenty-five per cent of Meta’s revenue is generated in Europe, which is too big of a share to lose. Consequentially, Meta had to adapt its terms to European standards and has called for a US federal privacy law that converges with the GDPR in order to further increase legal certainty and interoperability.

Such lobbying efforts by US companies underscore the desire of private US actors to cooperate with Europe on digital and technological standards via the TTC in order to retain market access and sustain their growth. Their European counterparts are also highly involved with the TTC through formats such as the Commission’s online consultation platform for stakeholder involvement in shaping transatlantic cooperation. All in all, Europe is dependent on US technology while US companies are dependent on access to the European internal market. There are several contentious issues that need to be addressed in order to make transatlantic cooperation and trade more efficient and sustainable. EU policymakers are well-advised to remain cognisant of the success that the digital foreign policy strategy of the Brussels effect has already yielded for the EU and to pursue this strategy further, as some topics of transatlantic dispute remain.

“Gatekeepers” of the Digital Market

Conflicts between the partners on both sides of the Atlantic have arisen regarding the planned designation of gatekeepers, which will primarily apply to non-European companies such as social media platforms mentioned above and digital marketplaces such as America’s Amazon or eBay and China’s Alibaba. Compliance of such companies with the provisions laid out in the DMA would mean fundamental changes to their established business models, which are based on offering free use of their platforms to private users and third commercial actors in exchange for their data and an opportunity to increase the platform’s growth. As access to the marketplaces is free, consumers can easily find an SME advertising its products there and then purchase from the SME directly, often at a cheaper price. This means that the gatekeepers need to advertise their own products more prominently in order to profit as well. While some observers caution that the definition of gatekeeper should not be too broadly interpreted, and that the designation of gatekeepers should focus on companies with little competition, such as Google – which has a market share of almost 90 per cent in Europe – American partners are concerned that US companies are specifically being targeted, and thus are calling for a broader interpretation of the term. This has created a dilemma for the DMA in terms of preventing discriminatory practices by market leaders while adopting non-discriminatory regulations to address data sovereignty and fair competition on the digital market.

Furthermore, US policymakers have expressed security concerns about requiring the possibility to distribute programmes such as apps outside of “closed systems” – in other words, to install apps on smartphones and other devices without relying on the two dominating market powers, Apple (iOS) and Alphabet (Android). However, this also means that the cybersecurity of smart devices can be compromised by downloading malicious software from a third source without established vetting and verification processes.

The EU has set precedent in issuing such decidedly antitrust regulations for the digital market, such as the DSA and the DMA, and thus set the scene for the transatlantic debate. In the negotiations to come via the TTC, it would be best for the EU to insist on the framework created by the DSA and the DMA for fair competition and data protection while engaging both private actors and transatlantic partners in the design of specifications and further provisions. This approach could be especially efficient, as the US is currently debating anti-trust legislation concerning big tech companies as well. Given that digital services are “indivisible”, as Bradford puts it, US companies updated their terms of service in accordance with the GDPR, which constitutes the world’s strictest and most detailed data protection regulation, as it would simply be too costly to offer a different service model across different countries. As the DSA and the DMA are already in place, the EU has provided a framework for the transatlantic debate, which needs to be specified and fleshed out through a multi-stakeholder effort such as the TTC.

Schrems II and Legal Certainty

Another point of disagreement are data protection regulations, especially since the European Court of Justice (ECJ) voided the “privacy shield” (the transatlantic agreement regulating the exchange of users’ private data between European company subsidies and their American holding companies for commercialisation purposes) in Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited and Maximilian Schrems in July 2020. Until now the EU has failed to implement a new framework, with dire consequences for the companies concerned. For instance, the Austrian data protection authority banned the use of the data analysis tool Google Analytics, which was a significant setback for Google but also for Austrian companies utilising the tool. Following the ruling, the EU Cloud CoC General Assembly, which includes international companies, started to work on the Third Country Transfer Initiative, which seeks to address concerns regarding the processing of European users’ personal data in a third country by developing a specific “module” to complement the GDPR. However, so far, no third-country module has been introduced, as it remains unclear how such a module should be designed to comply with the ECJ’s expectations.

A feasible solution for providing legal certainty for transatlantic data transfers is urgently needed, as interoperability is crucial for the provision of digital services and the pursuit of further business opportunities in Europe, both by American companies and European companies working with American digital products. This is an issue of significant importance. The EU should seek to finally agree on a replacement for the EU-US privacy shield to provide legal certainty for European companies using American services, and for American companies seeking to design products for the European market. The nomination of an oversight board might be a feasible step towards the institutionalisation of the Third Country Transfer Module, as such watchdogs and their ability to issue fines have successfully mediated company practices and GDPR regulations in the past, for instance in the cases of GDPR violations by TikTok and Facebook.

Institutionalising a replacement for the privacy shield first requires a joint European effort to agree on a feasible alternative, which is only achievable through deepened integration. The establishment of a replacement for the privacy shield would not only mean a further step in the process of European internal re-sovereignisation It would also be an important signal reaffirming European external digital sovereignty, as GDPR provisions have been successfully externalised via the Brussels effect in the past, and further strengthening the regulation and its international implications is necessary to underscore the GDPR’s durability and credibility.

Setting the Agenda for Transatlantic Cooperation

Transatlantic cooperation and European technological sovereignty can appear to be mutually exclusive. For instance, the EU Chips Act calls for greater public investments in semiconductor R&D in Europe, whereas the American CHIPS Act, passed in June 2020, calls for investments in chip design R&D in America. Concerns about an emerging and counterproductive “subsidy race” have been voiced on both sides of the Atlantic. Careful leverage of the Brussels effect could also remedy this issue: Both American and European policymakers understand that a strictly US or EU focus on reclaiming technological sovereignty is unrealistic, which is why they are discussing areas in which international cooperation is inevitable, such as the procurement of rare earth elements necessary for chip production, via a TTC working group. This debate should also include considerations of an expansion of the TTC, for instance to include Canada, which is also committed to democratic technology governance and can certainly offer resources that are in demand.

As both the EU Chips Act and the US CHIPS Act have only been issued recently, the EU should seize the opportunity to facilitate transatlantic research cooperation and set regulations for both the semiconductor market competition and the technological capabilities of such products – similar to AI regulation – in order to outlaw the inclusion of specific features that make chips made in Europe or the US vulnerable to espionage or sabotage. Transnational cyber threats such as technological backdoors can only be combated if such equipment has equal certification in both the US and the EU. Although only the US currently has sufficient capabilities and expertise to compete with companies such as Huawei, whose products do not meet certification standards, the EU can set the agenda for spelling out the details of future cooperation on – and governance of – democratic technology, as it already successfully has in the case of AI technology. The case of Huawei equipment also illustrates that companies not willing to comply with EU standards face market exclusion, which the EU should emphasise when it wants to protect its citizens’ data from US intelligence agencies as well.

The Way Forward

The path ahead can only be international, and especially transatlantic: American companies are dependent on access to the European market to sustain their growth, and in turn, European citizens and companies (as well as public administrations) are dependent on products offered by American digital technology companies in their daily lives and operations. Moreover, the US and EU constitute the biggest markets, which are also liberal democracies, in a world where autocracies are on the rise, and they share key values such as the right to privacy and free speech as well as a commitment to free and fair economic competition. All of this makes a strong case for transatlantic cooperation in advancing digital development and democratic technologies. Leading up to the spring meeting of the TTC, European policymakers should continue their approach of leveraging the Brussels effect in order to ensure and enhance compliance with the European standards of fair market competition and data protection. At the same time, it is important to keep the door open for negotiations regarding the specifics of relatively new provisions such as the DMA’s designation of gatekeepers – the EU has established a pioneering framework for the digital market and should now continue its approach of multi-stakeholder involvement as the regulations are translated into company practices and further spelt out. In order to enter such negotiations with a coherent approach and credible mandate – and thus be able to secure and manifest external digital sovereignty – it is crucial to further advance the process of European internal re-sovereignisation, such as by agreeing on a replacement for the privacy shield. EU regulations developed in the European comitology procedures have been successfully externalised via the Brussels effect in the past, even despite strong initial opposition, and the EU should strive to continue this method, and thus strive to deepen integration.

Dr Annegret Bendiek is Deputy Head of the EU / Europe Research Division at SWP. Isabella Stürzer is a Student Assistant in the EU / Europe Research Division.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2022

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

doi: 10.18449/2022C20