Contours of an EU Partnership and Alliance Strategy

How Europe Plans to Strengthen Its Security with Partners beyond the United States

SWP Comment 2025/C 29, 23.06.2025, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2025C29

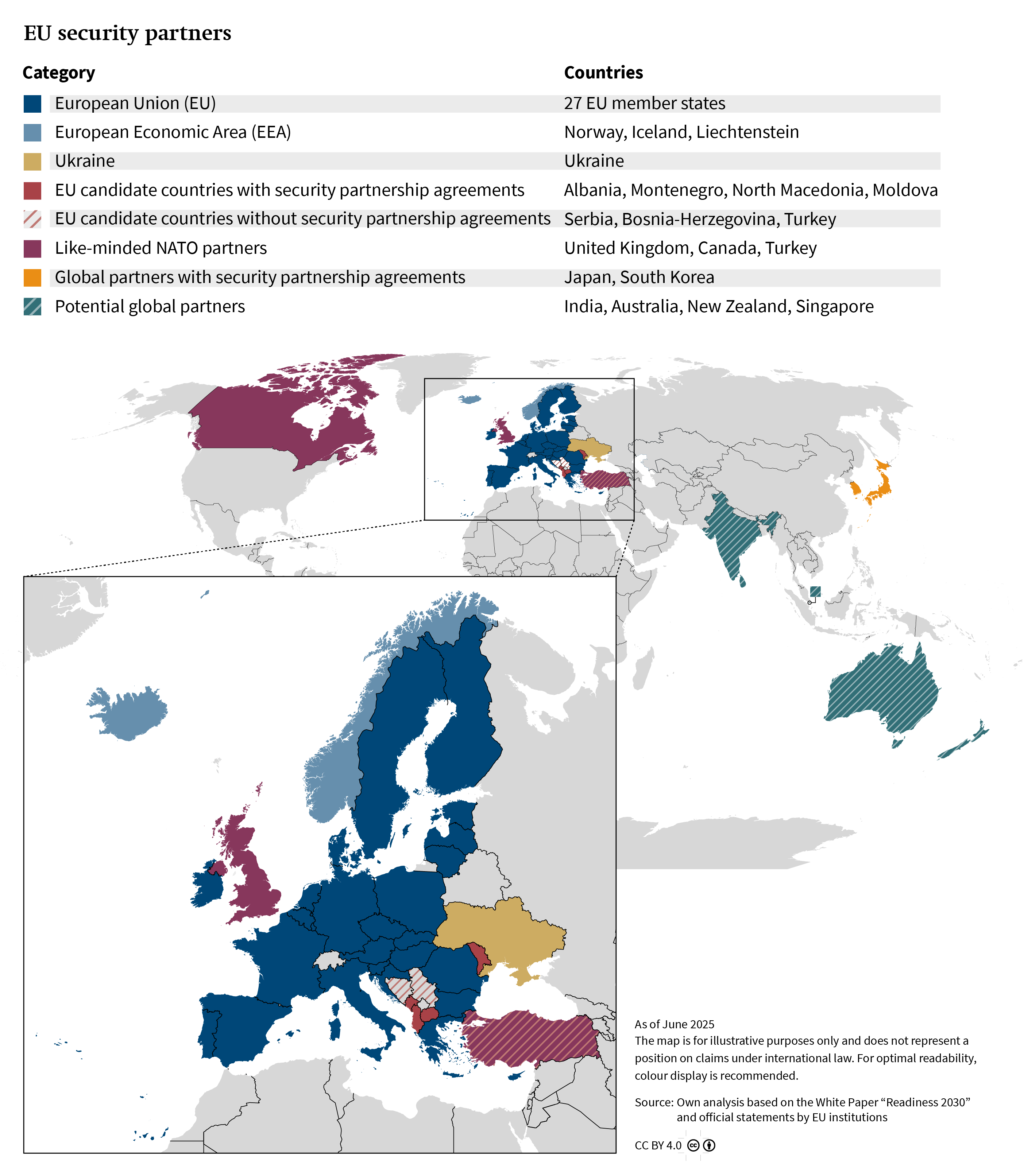

Research AreasEurope must take more responsibility for its defence, if necessary without the United States, given Washington’s volatility. In March 2025, the European Union (EU) launched a series of initiatives to strengthen defence industry and defence policy cooperation. With these new instruments also come the outlines of a new partnership strategy. Previous Brussels formats for defence industrial cooperation were only open to members of the EU and the European Economic Area (EEA). The Security Action For Europe (SAFE) Regulation – adopted by the EU in May 2025 – on the other hand, provides for a level of integration of Ukraine in this sector that comes close to that of an EU member. With the United Kingdom, the EU has created new opportunities for participation for the first time since Brexit via a security partnership agreement. The EU also wants to offer countries such as Canada, Turkey, Japan, South Korea, Australia and even India points of contact via partnership agreements. In order for this strategy to be successful, the EU needs to make itself a more attractive partner.

Since the United States, under President Donald Trump, has implemented a change of strategy in its Ukraine policy and is conducting direct negotiations with Russia without the Europeans, the European security order is in a phase of reorientation. Old certainties are dissolving, in particular the firm belief in the American security guarantee via NATO. The new prevailing tenor is that Europeans must take more responsibility for their own security as quickly as possible and invest massively in their defence and arms industry.

The institutional component of this reorganisation remains complex, as does the question of who exactly belongs to “Europe”. NATO continues to form the central framework for common defence – with a stronger focus on its European pillar – while France and the United Kingdom are forging a Coalition of the Willing for a possible mission in Ukraine. The EU, meanwhile, is aiming to improve its industrial and fiscal foundations for a more autonomous European defence capability.

To this end, the EU has published a White Paper on defence entitled “Readiness 2030” and launched a series of instruments to support the member states in the area of armaments and strengthen cooperation. These include the SAFE Regulation, adopted in May, with which the EU intends to raise 150 billion euros and make it available to the member states as loans. Other instruments include the use of “national escape clauses” in EU fiscal rules to exempt national defence spending – initially for four years – the mobilisation of private capital, and procedures and incentives for joint defence procurement.

Opening up to EU partners

It is this area of joint procurement and joint investment in the European defence industry for which EU states have agreed a new approach to the Union’s partners at the proposal of the European Commission. The Commission is building on the Strategic Compass of 2022, according to which security partnerships should form one of the pillars of EU foreign and security policy (see SWP Comment 3/2022).

First, the EU wants to play a much bigger role in the defence industry. Until now, the EU has only played a subordinate role in this policy area. Military procurement is largely excluded from the regular rules of the internal market (see Art. 346 TFEU). Instruments such as the European Defence Fund (EDF) had too limited a size to make them relevant for corresponding decisions by member states. This is now set to change with the SAFE Regulation, which is a platform for joint procurement and other initiatives.

With its previous defence cooperation instruments, the EU was very selective when it came to the involvement of friendly third countries. It does not have an overarching set of rules for such cases, but rather slightly different guidelines for cooperation with the European Defence Agency (EDA), involvement in selected projects under the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and participation in the EDF (see SWP Working Paper, Research Division EU/Europe 2/2025). For example, more than 20 countries have concluded agreements to participate in EU operations. The United States, Canada and, in future, the United Kingdom are participating in the PESCO project for military mobility. However, the EU had previously drawn a clear boundary: With a few exceptions, defence industry cooperation was only open to EU members and countries that are linked to the EU internal market via the EEA – the latter applies in particular to Norway. Of all the non-EU states, Norway has therefore been the most closely integrated into the instruments of Brussels’ defence policy, in some cases even more so than some EU states such as Malta, Ireland and Austria. This applies, for example, to PESCO projects, participation in the EDF and EU operations, as well as involvement with the EDA.

Other NATO but non-EU states such as the United Kingdom and Turkey were denied participation. The White Paper on defence and the SAFE Regulation introduce a potential reorganisation of partnerships here. SAFE loans are reserved exclusively for EU member states. However, the offers for third countries to participate in joint procurement are no longer based purely on the logic of integration, and thus require membership in the internal market; instead, the EU is opening up to selected partners with which it has concluded security partnerships, thus turning a legal requirement into a political choice. At the same time, this procurement should primarily (at least 65 per cent) include components from European defence companies, potentially involving those based in partner countries. In parallel, EU leaders began consulting “like-minded” NATO partners the day after the European Council meetings in March 2025. The countries discussed below are in the foreground.

Special role for Ukraine

Ukraine plays a remarkably prominent role. In the SAFE Regulation, with few exceptions, it is put at the same level as EU members, analogous to the EEA states. This is surprising insofar as Ukraine, unlike the EEA members, does not participate in the EU internal market. Nevertheless, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is striving for close integration of the Ukrainian defence industry, which is developing rapidly under the pressure of war, for example with regard to drones and AI technology.

Ukraine’s special status goes even further. EU member states wishing to apply for SAFE loans are required to submit a “Defence Industry Investment Plan” to the Commission. This should not only specify any planned purchases, but also emphasise its own steps to support Ukraine and its participation in joint procurement (Art. 7 para. 2 SAFE Regulation).

The 65 per cent target is to apply to all businesses based in the EU, the EEA and Ukraine – without Kyiv having to conclude a partnership agreement. This is intended to accelerate links between the Ukrainian and EU-European defence industries, but it also represents a remarkable example of gradual integration into the EU, long before the desired full membership. Last but not least, the Ukrainian president has attended most of the European Council meetings since 2022 as a guest for individual agenda items – whether in person or via video link.

New security partnership with the United Kingdom

The EU has also explicitly created new opportunities for the United Kingdom. During the Brexit process, London withdrew from any institutionalised cooperation with the EU in matters of security and defence policy. However, a rapprochement has been taking place since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022; the current Labour government has been working towards an EU-UK security pact (see SWP Comment 27/2024). Nonetheless, the existing third-country rules, which clearly exclude countries outside the EU internal market from defence industry cooperation, would have severely limited the scope of such a security pact.

The SAFE Regulation and the White Paper on defence now stipulate that joint procurement and the modalities of origin can be extended beyond EU and EEA members and Ukraine to “like-minded” states that have negotiated a security partnership agreement with the EU. EU leaders explicitly include the United Kingdom among these “like-minded” states and concluded a Security and Defence Partnership Agreement with it in May 2025 at the first EU-UK summit since Brexit.

This agreement sets a new course in four respects. Firstly, it closes one of the gaps in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, which was concluded after Brexit in a phase when the British – under Prime Minister Boris Johnson – were still explicitly ruling out structural cooperation with the EU in foreign and security policy matters. In contrast, regular formats for exchange are now being created between the High Representative and the British Foreign and Defence Secretaries, as well as at the working level between the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the relevant British ministries.

Secondly, the agreement – in combination with the SAFE Regulation negotiated at the same time – lays the foundation for the United Kingdom to participate in joint procurement in the EU without being in the internal market. However, in order to realise this and to determine the conditions under which British defence companies fall under the 65 per cent internal procurement target of SAFE, a further agreement is required and is currently being negotiated. Thirdly, the partnership agreement also contains a series of declarations of intent to deepen EU-UK cooperation in security and defence policy. These include a framework agreement for British participation in civilian and military EU operations, an agreement on administrative cooperation with the EDA and cooperation on military exercises, including the exchange of personnel between the EU and British institutions.

Fourthly and finally, a broad range of topics was defined on which cooperation would be intensified. These include regional security (such as Ukraine, the Western Balkans, the Arctic and the Indo-Pacific), the coordination of sanctions, maritime security, armaments policy initiatives, cyber security, coordination in international organisations, external economic security, migration, the climate and security nexus, and global health. Alongside Norway, this potentially makes the United Kingdom the EU’s closest security partner – if the declarations of intent are actually pursued.

A difficult balancing act with Turkey

The cooperation with Turkey poses other challenges. On the one hand, the country has the second-largest armed forces in NATO; it has built up a substantial defence industry, for example in the drone sector, and already has arms agreements with individual EU and NATO states such as Poland, Spain and Italy. The country’s strategic importance for the Black Sea region, the South Caucasus and the Middle East has also increased. On the other hand, security relations between the EU and Ankara have been de facto blocked since 2004 due to the Cyprus conflict. Although Turkey has participated in previous military operations within the framework of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), it has so far been excluded from all arms policy initiatives such as PESCO, the EDF and the EDA. In regions with a large Turkish military presence, Ankara also acts as a strategic rival to (parts of) the EU, for example in the case of Syria. Last but not least, the trend towards the autocratisation of Turkey has recently accelerated. It was particularly striking that the arrest of Istanbul’s mayor and Erdoğan rival, Ekrem İmamoğlu, in March 2025 took place shortly after the invitation to the strategic exchange with the EU. The official criticism from Brussels was correspondingly cautious.

In view of this balancing act, which is not new, it is all the more remarkable that the EU is becoming more open to involving Ankara in security policy. Turkey was always invited to the consultations with like-minded partners following European Council meetings. It has also been represented in the British-French strand of the Coalition of the Willing since the London meeting on 2 March 2025, and it has publicly offered the prospect of participating in a mission to monitor a potential ceasefire in Ukraine.

For its part, the Commission has proposed in the SAFE Regulation that all candidate countries – including Turkey – can participate in joint procurement projects. Conversely, however, defence products from Turkey and other candidate countries are not automatically included in the “European” share, unlike goods from Ukraine. The (albeit cautious) rapprochement with Turkey is particularly evident when contrasted with the approaches to other candidate countries beyond Ukraine, which were not included in the exchange formats that have now been carried out twice following the European Council meetings in March 2025. This also applies to Montenegro, Albania and North Macedonia, which have already joined NATO. However, the EU has already concluded security partnerships with the latter two. There are also question marks over how to deal with Georgia: Legally, it is now a candidate country and thus would fall under the category of partners under SAFE. The EU also conducted a regular security dialogue with Georgia up until 2024. However, since the Georgian government has recently turned towards Russia, the accession process has been de facto halted and concrete defence industrial cooperation is unlikely as long as the political situation in Georgia does not change.

Strengthening global partnerships

Beyond the EU’s direct neighbourhood, the EU also wants to conclude further security partnerships. Of particular importance now is Canada, which has been hit with particularly high tariffs by the Trump administration. Additionally, President Trump regularly threatens to make it the “51st state” of the United States. As a result, the EU is coordinating closely with Canada on trade issues and has already begun negotiations on a security agreement. The latter is to explicitly include a defence industry component so that the country can participate in joint procurement and Canadian products are included in the “European” share. In a break from tradition, Canada’s new prime minister, Mark Carney, did not travel to the United States for his first visit abroad, but to France and the United Kingdom. The upcoming EU-Canada summit, which both sides are planning on the eve of the NATO meeting at the end of June 2025, will also focus strongly on security and defence cooperation. The EU has also been conducting a security dialogue with NATO member state Iceland since 2023.

The EU’s most prominent global partners are Japan and South Korea. It has long maintained comprehensive free trade agreements with both countries and has also had a security agreement with each since the end of 2024. South Korea has now become an important defence supplier for individual member states such as Poland (see SWP Research Paper 2/2023). Both countries have supported Ukraine financially and with arms deliveries, also as a signal to China with regard to Taiwan. Security policy cooperation is also to be explored with Australia, with which the EU is negotiating a free trade agreement, and with New Zealand, with which such an agreement has been in force since 2024.

The EU is also emphasising India as a potential partner (see SWP Research Paper 17/2024) and has been holding regular consultations in recent years. An EU-India free trade agreement is being sought, although the negotiations are complex. In February 2025, the entire von der Leyen Commission visited the country – the first non-European trip in the new term of office. Among other things, it was agreed in New Delhi to examine a possible security partnership agreement. The EU also wants to establish a security dialogue with Singapore.

Key aspects of the existing security partnerships

The EU’s interest in its own security partnerships is not entirely new. Even before the new agreement with the United Kingdom, it had already concluded a whole series of them in 2024, namely (in the order in which they were signed) with the Republic of Moldova, Norway, Ukraine, Japan, South Korea, Albania and North Macedonia. What all of these security partnership agreements have in common is that they emphasise a common set of values and their threat analyses focus on the same dangers – such as hybrid attacks, cyber attacks, international terrorism, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and threats to international organisations. However, they are not mutual assistance agreements. Concretely, all six agreements mention participation in EU missions and operations, structured dialogue on security issues and potential coordination in international forums. An institutional framework is also created for each of these, including annual EU summits with Japan and South Korea as well as strategic dialogue formats at working and ministerial levels.

The differences between the agreements lie primarily in the depth of cooperation and diverging priorities. For example, the agreement with Norway is the most extensive and most concrete, analogous to previous cooperation agreements. If the parties follow through on the various declarations of intent, the United Kingdom will come close to a similar level. An expected difference between the security partnerships with Japan and South Korea is that the agreements in question do not mention support for Ukraine or cooperation on border protection, but instead place a greater focus on maritime security and the protection of trade routes. These two agreements also contain a declaration of intent for an agreement on the security of classified information, as the EU already has with the other four countries, as well as the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States.

In their current form, the security partnership agreements are therefore primarily symbolic and aimed at strengthening coordination, as there are no mutual promises of assistance. Many aspects such as joint exercises and participation in CSDP operations initially remain at the level of declarations of intent. As far as the defence industry is concerned, only consultations are envisaged in each case; however, the agreements to date do not yet contain any provisions on participation in CSDP instruments. On the basis of SAFE, it would now be conceivable to involve the states concerned in joint procurement. However, in order for the states to benefit more extensively from the new instrument and be able to count their own defence industry towards the minimum 65 per cent share, they – as well as the United Kingdom and the candidate countries – would still have to conclude a separate agreement with the EU on SAFE.

Partnerships on three levels

In the future, the EU’s defence and armaments policy initiatives will not only strengthen European resilience and industry, but also create a new network of partnerships. If one examines the list of existing and potential partners, the contours of an EU partnership and alliance strategy can be recognised on three levels.

Firstly, the members of the EEA will continue to be the most closely integrated and connected. This applies in particular to Norway, which is more closely integrated into the CSDP structures than some EU states. What is new, however, is that Ukraine is largely treated as an EU member in SAFE, and EU states that use the instrument benefit particularly from cooperation with Kyiv.

At the second level are “like-minded” NATO partners outside the EU, with whom the Brussels leadership has already held consultations after the successive European Council meetings in March. The United Kingdom is of particular importance here. The Security and Defence Partnership Agreement with London now opens up the prospect of defence policy and defence industry cooperation, which could also include British participation in joint procurement – although details, including the modalities of participation in SAFE, still need to be negotiated. This will require both sides to overcome old Brexit traumas. Canada is also turning towards the EU and the Europeans in the face of constant threats from Washington. The relationship with Turkey remains complicated but could also lead to a security partnership.

Global partners are located at the third level. Among these, the EU has already concluded security partnerships with Japan and South Korea, but these have so far mainly comprised declarations of intent, coordination formats and diplomatic friendships. Other potential partners are Australia and New Zealand, as well as India and Singapore.

The EU needs to make itself an attractive partner

The most important prerequisite for the success of this alliance strategy is that the EU makes itself a more attractive partner. Only an EU that invests extensively in security and defence and in which such investments flow largely to its own industry and that of selected partners can offer full security agreements. SAFE needs to be widely utilised by the member states in order to succeed where previous EU initiatives have failed: namely in the development of joint procurement, financing and cooperation in the rearmament of Europe. The new German government should set a good example here. Then the EU can approach its partners with promising offers.

Cleverly designed EU partnerships should simplify the complex European security architecture, or at least not complicate it any further. Incompatibilities with NATO initiatives should therefore be strictly avoided. Conversely, EU projects can strengthen the European pillar of the alliance through close ties with NATO partners; this applies to countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway, Canada and (more limited due to the difficult relationship) Turkey.

In order to realise a genuine partnership and alliance strategy, the EU should work on linking the security partnerships with broader cooperation where possible – in trade policy, in the defence of the rules-based order and in geostrategic competition. The EU already has far-reaching trade agreements with important partners: from Norway’s EEA membership to the association agreements with Ukraine and other candidate countries; the Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the United Kingdom; and the free trade agreements with Canada, Japan and South Korea. The aggressive and unpredictable tariff policy of the US administration requires new partnerships that can be coupled with security cooperation. There are a number of options for this. For example, consultation mechanisms could be set up with partners in the event of – economic or military – pressure from third parties; dialogues on military security could be combined with those on economic security; or joint measures could be agreed on security-related topics, such as access to critical raw materials or the protection of supply chains and critical infrastructure. This also requires more synergies between economic and military security within the EU, in particular through coordination within the Commission and with the EEAS.

If Europeans want to avoid becoming a pawn of foreign powers in a world increasingly characterised by spheres of interest, they must summon the strength to become a pole of their own. Not all steps towards this must be taken within the EU framework, as the British-French initiative to support Ukraine shows. However, attractive EU security partnerships based on joint investments and a strengthening of Europe’s own defence industry – coupled with the expansion of trade relations – can serve as a powerful instrument. This should also make it possible for the EU and the European pillar of NATO to avoid being played off each other in Europe’s security architecture. Instead, the EU should endeavour to combine its strength in the internal market with effective security partnerships.

Dr Nicolai von Ondarza is Head of the EU/Europe Research Division at SWP.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C29

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 28/2025)