A Migration Miracle? Indian Migration to Germany

Opportunities and Challenges

SWP Research Paper 2025/RP 04, 15.09.2025, 35 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2025RP04

Research AreasDavid Kipp is an Associate in SWP’s Global Issues Research Division. This Research Paper was written as part of the “Strategic Refugee and Migration Policy” project, which is funded by the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The author would like to thank Emma Landmesser, Janna Langosch and Arthur Buliz for their support.

-

The number of Indian migrants in Germany has risen sharply in recent years. In particular, they are helping alleviate the shortage of skilled workers in STEM professions.

-

For Germany, India is the most important country of origin for labour and education migration. Currently, the profile of migration to Germany is changing: fewer experts are entering on the EU Blue Card (which, until recently, was the most important residence permit for skilled workers), while more students, trainees and professionally qualified people are coming to look for jobs or have their qualifications recognised by the German authorities.

-

The Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement (MMPA) concluded by Berlin and New Delhi in 2022 does not expand the German legal framework for recruiting skilled workers through the provision of new access routes. However, it does improve the practical implementation of self-organised migration from India – for example, by speeding up visa procedures.

-

The MMPA Joint Working Group offers the opportunity not only to engage in a dialogue with the Indian government aimed at harnessing the full potential of increasing migration but also to address the challenges that have arisen from that trend, including the inadequate regulation of private recruitment agencies.

-

The example of India shows that Germany’s external infrastructure and migration-related development cooperation must be used much more effectively in countries of origin in order to develop new approaches to the fair and successful recruitment of skilled workers for the German labour market.

-

Migration cooperation is a bridge builder in German-Indian relations, which are becoming increasingly important. Key areas of bilateral collaboration – such as digitisation, artificial intelligence and climate protection – should be systematically linked to knowledge exchange and the mobility of skilled professionals in these sectors.

Table of contents

2.1 Historical and social factors

2.2 Recent trends in international migration

2.3 The development of Indian migration to Germany

3 Foundations, legal framework and actors in German-Indian migration cooperation

3.1 The foundations of bilateral migration cooperation

3.1.1 The Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement

3.1.2 Skilled Labour Strategy for India

3.2 Legal framework and state actors

3.3 Non-state recruitment actors

4 Migration Cooperation: Opportunities and Challenges

4.1 Different approaches to migration cooperation

4.2 Skills matching for labour migration

4.3 Education migration – High level of interest demands improved selection procedures

4.4 Return policy – (not) a major problem

5 Enhancing Germany’s External Infrastructure in India

5.1 Improvement of Germany’s external infrastructure

5.2 Redefining migration-related development cooperation with India

5.3 Approaches to EU cooperation with India

Issues and Recommendations

The new German government emphasises that its migration policy aims to limit irregular arrivals and strengthen state control over migration processes. It is paying less attention, however, to the challenge of further developing skilled migration from third countries so that the demographic decline in the working-age population of Germany can be addressed. While the German government intends to establish a digital central agency (the so-called Work and Stay Agency) in order to boost the effectiveness of the procedures required for the migration process and the recognition of qualifications of applicants, such measures alone will not suffice to achieve the desired number of skilled workers recruited from abroad. Even an up-to-date legal framework and digital procedures will have the hoped-for impact only if a sustained effort is made to cooperate on migration policy with countries of origin. This is clearly evident in the case of India, the country that has become the largest source of labour and education migration to Germany.

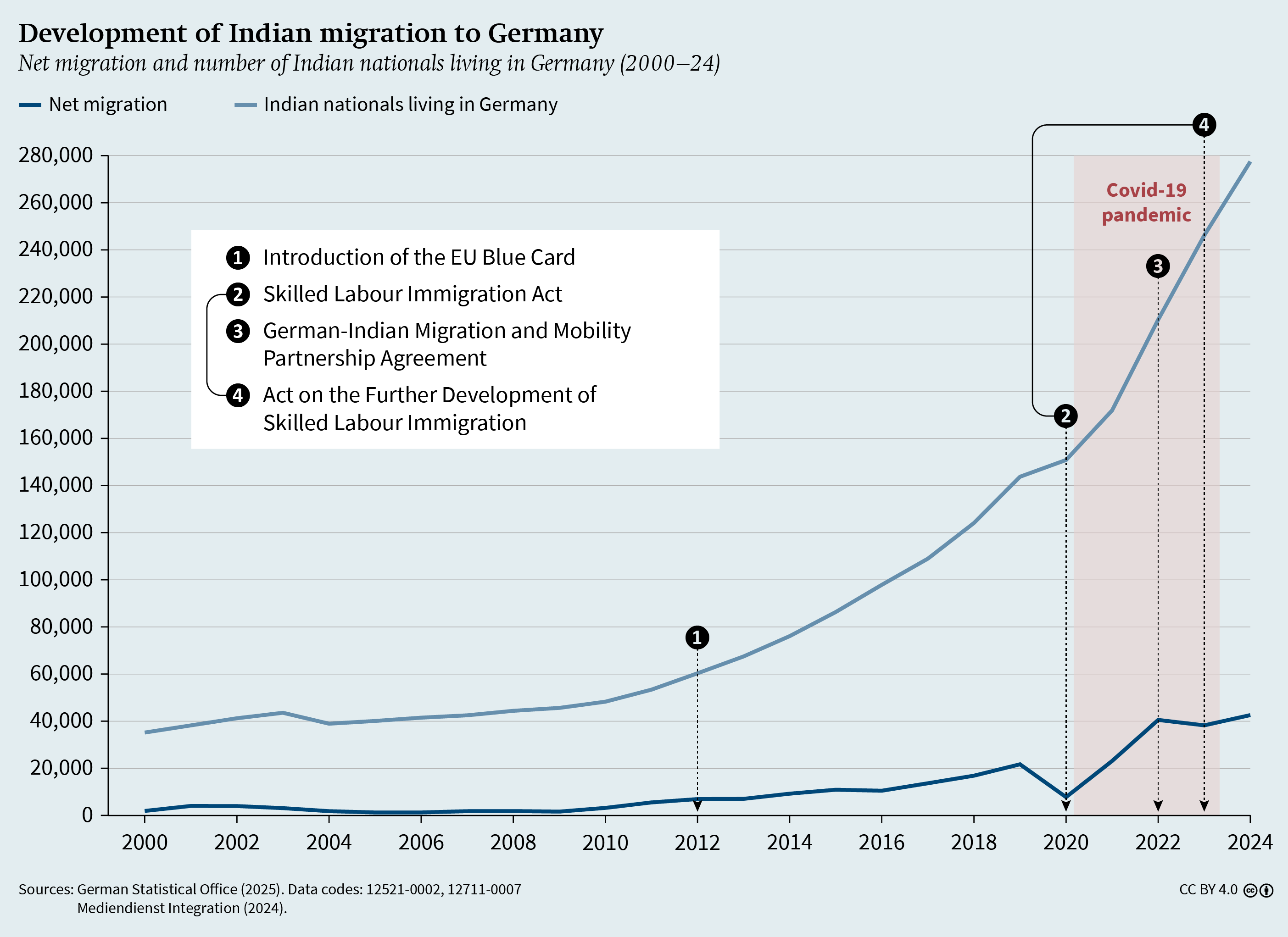

The number of Indian nationals in Germany has more than tripled over the past decade – from 86,000 in 2015 to 280,000 in 2025 – while the already low number of asylum applications from India has continued to fall. The majority of Indians employed in Germany are highly skilled workers in natural sciences, (information) technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and there are now more than 50,000 Indians currently studying at German universities. As a result, Indian migration to Germany is considered a success story. Some observers even speak of a “migration miracle”.

In 2022, Germany signed a Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement (MMPA) with India. The aim of that agreement is to further improve the conditions for “safe, orderly and regular migration” from India to Germany. This research paper examines the learning processes that can be observed in German migration policy amid deeper migration cooperation with India and considers the opportunities and challenges arising from Indian migration to Germany.

India has a large number of institutions, programmes and bilateral agreements devoted to migration cooperation. On the one hand, the Indian government is interested in alleviating pressure on the domestic labour market, where 7–9 million new jobs need to be created each year for the growing working-age population. On the other hand, it is seeking to harness migration as a tool to deepen foreign relations, enhance the strategic role of the diaspora and ensure the steady inflow of remittances. Measured in terms of these ambitions, migration governance is weak in India, partly because the long-overdue reform of its migration law has been repeatedly postponed. At the level of central government, there is a lack of trustworthy partner institutions for the overseas recruitment of skilled workers. So far, German recruitment efforts have focused on the subnational level, that is, the Indian states, some of which have structures that inspire more trust than those of the central government.

But when Indians want to go abroad to work, study or undergo training, most of them turn to private recruitment agencies rather than state institutions. Together, these agencies form a migration infrastructure that has grown over the decades and enables migrants to identify the fastest and easiest migration routes to different destination countries. However, fraudulent business practices are frequently reported owing to the lack of transparency, quality standards and government regulation.

Recently, many private recruitment agencies have been stepping up their activities in Germany. One reason for this is that since the reform of its Skilled Labour Immigration Act, Germany has become more open for skilled workers and students. By contrast, traditional destinations for Indian migration – such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia – have become more restrictive. Elsewhere, the Gulf states still attract mainly low-skilled Indian migrants, who continue to live and work largely in poor conditions in those countries. Although private recruitment agencies are extremely important for the migration of Indians, they are not mentioned in the MMPA – an omission that the German government corrected in its “Skilled Labour Strategy for India”, adopted in October 2024. This is a good starting point for engaging with the Indian government in the MMPA Joint Working Group with a view to developing new instruments that take into account the important role private agencies play in the recruitment of skilled workers and at the same time ensure they are better regulated.

The number of Indian students at German universities is steadily increasing. Despite its internationalisation since the mid-2000s, the German higher education system is not yet sufficiently equipped to deal with the large number of students from India. For example, there are no reliable selection methods for the numerous applications from India, which makes quality control difficult. And despite the great labour market potential of Indian students, instruments for integrating them into the German economy are not yet sufficiently developed. In addition, under the business model developed by some private recruitments agencies in India working with various private universities in Germany, young Indians pay high fees for a place at university only to find out that in some cases, the study conditions are poor and their degree is of limited value. Because of the large debts they have incurred, many Indian students depend on short-term ways of earning money in the gig economy. This means working in services such as food delivery, which, arranged via platforms, do not offer a permanent employment relationship.

Despite the challenges, Indian migration provides many opportunities. Germany’s intensified cooperation with India in this policy area should be seen in the context of the latter’s growing international importance. Moreover, migration plays a crucial role as bridge builder for the strengthening of bilateral relations. This is a process that necessitates the creation of synergies with other areas of cooperation. In the case of Germany, the extensive bilateral development cooperation with India should be further opened up to migration-related cooperation. The aim should be to work with Indian partners to establish the structural conditions that make migration from India to Germany (and other destination countries) as fair as possible. Finally, at the EU level, it should be ensured that the cooperation efforts of the individual member states do not work against one another and the EU’s instruments for cooperation in migration policy are brought up to date.

Trends in Indian Migration

With a population of 1.46 billion, India is the most populous country in the world. Owing to its sheer size alone, it plays a particularly important role in international migration flows. While the migration of Indians to the Gulf states and traditional migration countries such as the US has grown over time, it is only in the past decade that migration via newer routes to Germany and other EU countries has gained significantly in momentum.

Historical and social factors

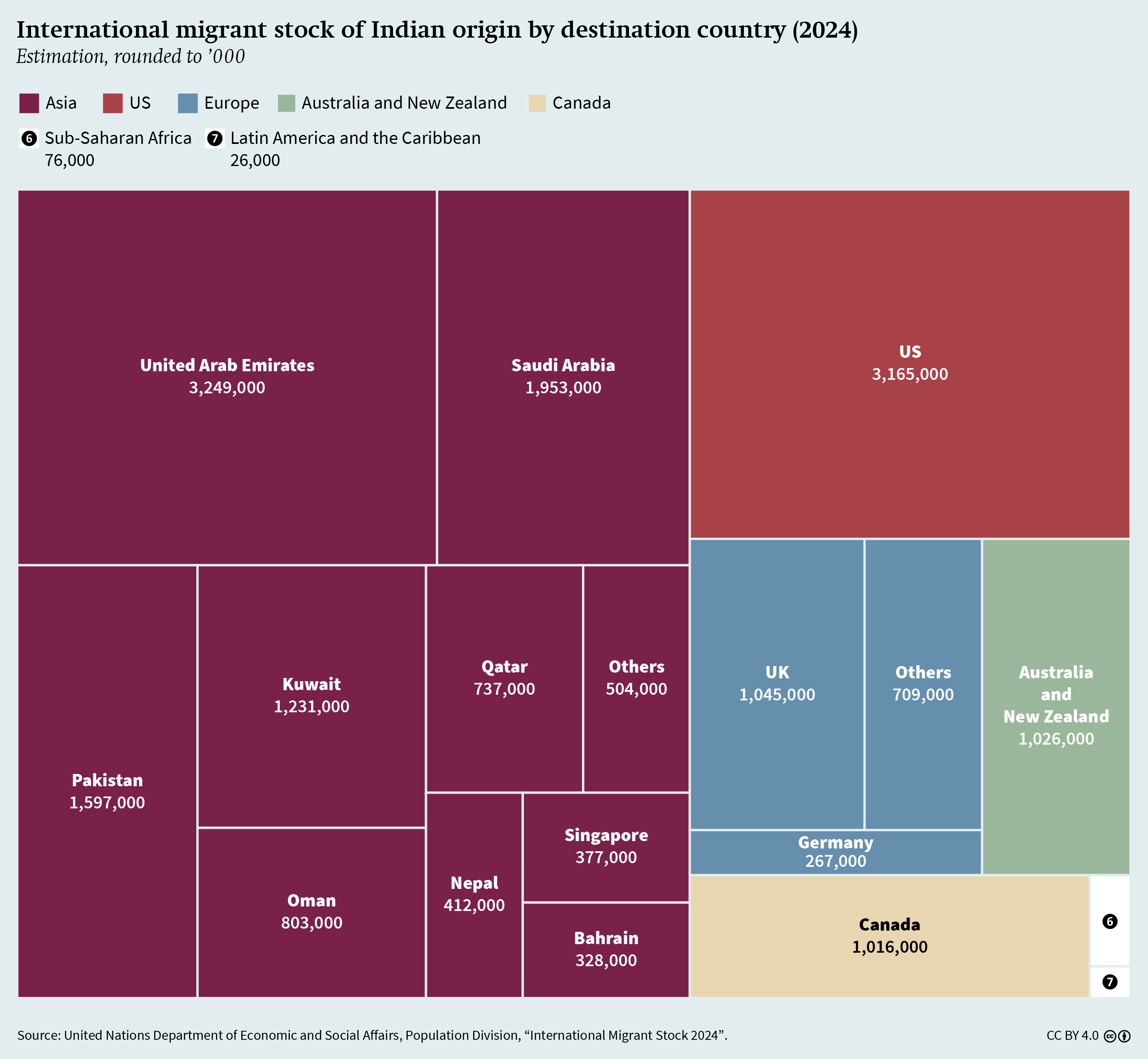

Contemporary migration from India cannot be understood outside the historical context. In the 19th century, British colonial rule established a system of temporary (forced) labour migration under which several million Indians were shipped to other British colonies around the world and exploited there.1 The British withdrawal from India in 1947 and the associated partition of British India into India and Pakistan were unique events both in terms of the scale and speed of the (forced) migratory movements. Four years after the partition, a total of 14.5 million people living in the region had been forced to flee.2 For a long time, this event continued to be reflected in the migration statistics of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), which until the mid-2000s listed Pakistan as the most important destination country for Indian-born migrants. However, this figure has fallen from 2.8 million in 1990 to 1.6 million in 2024.3

In the 1990s, migration from India to Western countries, primarily the United States, began to increase.4 In the West, Indian migrants have generally achieved an above-average socioeconomic status compared with the overall population. But the situation of Indian migrants who moved to the Gulf states from the 1970s onwards is very different. Those countries have attracted mainly low-skilled workers, who for decades have faced exploitation, poor working conditions and human rights violations.5 Even today, most Indian migrants there are employed in the low-wage sector of the labour market – on construction sites, in the hospitality industry or in transport and logistics – and often on a temporary basis only. In addition, Indian migrant workers’ wages have stagnated, while the cost of living in the Gulf states has soared in recent years.6 But none of this has deterred migration to the Gulf states. And for many Indian migrants, social expectations are another decisive factor: in states with a long tradition of migration, such as Kerala, individuals are often expected to pursue employment opportunities in the Gulf countries not least because of the prospect of comparatively high-earning opportunities owing to income disparities. In the Gulf states as a whole, incomes are on average about 120 per cent higher than in India; and in the UAE, they are up to 300 per cent higher.7

At the same time, Indian migration to the Gulf states is not limited to low-skilled workers; well-educated Indians have established themselves there, too.8 The latter often pursue highly skilled jobs in sectors such as healthcare, technology and finance but can also be found in management positions in large companies. The considerable influence of Indian nationals is also evident from their large-scale investments in the Gulf states. Particularly striking are the investments in real estate projects and the economy in Emirati metropolises such as Abu Dhabi and Dubai, where Indian nationals account for 30 per cent of all start-ups.9

The motives for leaving India are manifold. Among other things, migration decisions are influenced by the increasing autocratisation in the country and ongoing discrimination.10 An important factor in this context is religious and caste affiliation. For example, around 80 per cent of the Indian population are adherents of Hinduism, from which the caste system derives; and it is this system that shapes living conditions in rural areas. The migration of Hindus to countries such as Germany often means leaving behind the caste system, which can be perceived either as a deprivation or as liberation.11

In traditional migration countries such as the United States, many Indian migrants are from socially privileged classes.12 Religious minorities such as Christians and Sikhs are overrepresented in the US, too: in 2012, Christians accounted for 18 per cent of the total number of Indian migrants there (compared with 2.3 per cent in India) and Sikhs for 5 per cent (1.7 per cent). Hindus and Muslims, on the other hand, were underrepresented.13 Muslim Indians and lower castes have a relatively strong presence in the Gulf states. At the same time, caste discrimination persists in important destination countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States.14 California was the first US state to include this discriminatory practice in its anti-discrimination laws. The law defines “caste” as a system of social hierarchy that is often determined by birth and either confers social privileges or causes disadvantages.15

Recent trends in international migration

Figures for international migration from India differ significantly. While according to UN DESA there were around 18.5 million Indian migrants worldwide in mid-2024,16 the Indian Ministry of External Affairs puts the number at around 35.4 million.17 The difference arises because UN DESA counts only Indians born abroad while the Indian Ministry of External Affairs includes not only the 15.9 million so-called non-resident Indians (NRIs) but also the 19.6 million Indian nationals and descendants of Indian origin living abroad as persons of Indian origin (PIOs).

According to the UN DESA figures, the most important destination region for Indian migrants is the Gulf states, led by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with 3.2 million Indian migrants, Saudi Arabia with 2 million and Kuwait with 1.2 million. The Western industrialised countries are the second most-important group of destination countries. The United States has 3.2 million Indian migrants, almost half of whom have US citizenship;18 and the United Kingdom has some 1 million, although according to the 2021 British census, a similar number of British citizens are of Indian origin.19 It is unclear whether the UN DESA figures reflect the latest migration trends, as half a million Indians migrated to the UK in 2023–24 alone.20 Approximately 1 million Indian migrants live in Canada and, according to the 2021 census in that country, a similar number of Canadian citizens are of Indian origin.21

Education is an important driver of Indian migration; however, many Western destination countries want to limit the number of Indian students.

In Australia, the number of Indian migrants has doubled to 900,000 over the past decade. Student migration has played a significant role in that increase. Between July 2022 and June 2023, more than 100,000 student visas were issued. But at the request of the Australian government, this number was lowered to 50,000 for the period from July 2023 to June 2024.22 Similarly, both the Canadian23 and the British government24 have taken measures to reduce the number of migrants, which will make further migration from India more difficult.

Since President Trump took office for a second time, the United States has introduced various restrictions on Indian migrants and stepped up the deportation of those without valid residence status. In early 2025, the Indian government agreed to take back around 18,000 nationals who were living in the US illegally, hoping to thereby improve relations with Washington and secure legal visa programmes.25 However, the total number of Indian migrants without valid residence status in the US is significantly higher: in 2022, it was estimated at 375,000.26 In 2023–24 alone, almost 190,000 people arrived irregularly, mainly via the so-called donkey flight route, which is used by smugglers moving migrants from various Central American countries to the Mexican-US border.27 Alongside the US, Canada is increasingly becoming a destination country for Indian migrants; but at the same time it serves as a transit country for onward travel to the United States.

In addition, there have been isolated cases of Indian nationals attempting to enter the EU and Germany via Russia and Belarus.33 The prospects for Indian nationals seeking asylum in the EU are poor, even though the proportion of positive first-instance decisions on asylum applications across the EU rose from 1.8 per cent in 2022 to 2.3 per cent in 2023 and 4 per cent in 2024.34

The development of Indian migration to Germany

Migration from India to Germany – which was modest until the early 2010s – can be divided into four historical phases.35 In the 1950s, Indian engineering and medical students became the first to enter the Federal Republic in significant numbers. They were followed from the late 1960s onwards by 6,000 nurses from the state of Kerala, whose recruitment was organised by the Catholic Church.36 In 1970, there were around 8,000 Indian nationals living in Germany.37 The third phase was marked by the forced migration of Punjabis and Sikhs following the unrest in the Indian state of Punjab in the early 1980s. The number of Indian nationals in Germany subsequently rose to more than 28,000 but then declined somewhat until German reunification.38 In the German Democratic Republic, on the other hand, there was no systematic recruitment of Indian workers, although an unknown number of Indians studied there.39

The fourth phase of immigration began in reunified Germany between 2000 and 2004 with the introduction of the German Green Card.40 However, the initiative was of limited success, as fewer than 15,000 IT specialists were recruited, instead of the targeted 20,000.41 Of these new IT recruits, just under 4,000 came from India.

It was not until the introduction of the EU Blue Card, which was implemented in German law in 2012 that there was a quantum leap in the number of migrants from India. This new residence permit made it easier for third-country nationals to enter the EU for work purposes. From 2005 to 2015, the number of Indian nationals residing in Germany more than doubled – from 40,000 to 86,000. At the beginning of 2025, there were around 280,000 Indian nationals living in Germany as permanent residents,42 more than 152,000 of whom were in employment subject to social insurance contributions.43 With the exception of the coronavirus year 2020, net migration has grown steadily44; however, at the same time, the number of Indian nationals leaving Germany has risen somewhat in recent years.45

Migration movements from India to Germany are becoming more diversified.

Since the beginning of the 2010s, the gender distribution of migrants from India has changed, too: the ratio between male and female migrants, which was 70:30 in 2012,51 has narrowed to 60:40 in 2023.52 According to a survey conducted by the German Employment Agency’s research institute (IAB) in 2021, the majority of migrants from India want to stay permanently in Germany, while 37 per cent have already obtained German citizenship.53

In 2024, the number of visas issued for study purposes exceeded 25,000 and thereby surpassed those issued for labour migration.54 More than 50,000 Indian students were enrolled at German universities, making them the largest group of international students in the country (between the 2018–19 winter semester and the 2023–24 winter semester, their number increased by 138 per cent55). Not least because of its numerous universities, Berlin is the main destination for migration from India to Germany – more than 40,000 Indian migrants now live in the German capital (in 2014, there were just 3,50056) – followed by Munich and Frankfurt am Main. The growing number of Indian migrants is also reflected in the increasing flow of remittances from Germany to India, which, according to estimates by the Bundesbank, rose from €131 million in 2022 to €164 million in 2024 – an increase of around 25 per cent.57

Foundations, legal framework and actors in German-Indian migration cooperation

Having slowly gained relevance over the previous two decades, migration was finally identified as a new area of cooperation with the signing of the Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement (MMPA) at the German-Indian government consultations in Berlin in May 2022. The MMPA has strengthened cooperation efforts on both sides.58 And in the case of Germany, it was accompanied by the further liberalisation of the Skilled Labour Immigration Act and the introduction of the “Skilled Labour Strategy for India”.

The foundations of bilateral migration cooperation

The Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement

In the early 2000s, Germany paved the way for large-scale skilled labour migration from India through its programme aimed at meeting IT skills shortages (the Green Card) and, in the 2010s, through the EU Blue Card. At the same time (2011), Germany and India concluded a bilateral social security agreement on pension insurance. This agreement stipulates that social security contributions paid in one of the two countries are to be taken into account in the other country in order to safeguard pension entitlements.59

It took several years of negotiations for the MMPA to be signed. Initially, in 2019, the responsible German ministry – the Ministry of the Interior (BMI) – wanted to negotiate only a bilateral agreement on the readmission of Indian nationals.60 Inspired by the MMPA between France and India (signed in March 2018),61 the initiative for a broader agreement developed during the bilateral dialogue. In the end, the Indian-German MMPA was negotiated not by what at the time was the Grand Coalition but by its successor, the Scholz government, and agreement was reached during the German-Indian consultations in Berlin in May 2022. This was the first comprehensive bilateral migration agreement under the then new German government and was to be followed by others.62 The signing took into account India’s growing importance for Germany’s foreign policy, which had already been acknowledged in the government’s Indo-Pacific Guidelines of 202063 and was reconfirmed more recently (in October 2024) in a strategy paper titled “Focus on India”.64

Following the logic of the agreement between France and India, the MMPA aims to comprehensively regulate migration: it seeks, on the one hand, to promote the mobility of Indian students, trainees and skilled workers and, on the other hand, to strengthen readmission cooperation. While the German government has emphasised improved readmission cooperation,65 the Indian government has stressed the need for accelerated visa procedures.66 The former prefers the concept of “mobility” to that of “migration”, which it regards as having negative connotations. Because the MMPA is an agreement about both migration and mobility, a bridge that spans the two concepts is thus being built between the parties.

The agreement comprises a series of non-binding declarations of intent, which do not, however, go beyond the existing legal framework. The most concrete objective, which is set out in Article 6, aims to send at least 3,000 young professionals from India to Germany each year.67 In addition, detailed rules are laid down on the return of Indian nationals required to leave Germany, on voluntary return and reintegration, and on combating irregular migration and human trafficking (Articles 12–14). In accordance with Article 16, a Joint Working Group on Migration and Return Issues has been established. This group is to oversee the monitoring of the implementation of the agreement and will meet regularly (at least once a year). The BMI is the responsible ministry and the establishment of a separate sub-working group is planned to deal with issues related to the return of nationals required to leave. In April 2025, a sub-working group on labour migration was set up; the German Foreign Office (AA), the German Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS) and their Indian counterparts are in charge of this new group.

Germany’s MMPA with India – like the migration agreements that it has since concluded with Georgia and Kenya – is an international treaty. At the same time, the German government has reached informal agreements with Morocco and Colombia that allow for greater flexibility and for domestic sensitivities in the partner country to be taken into account.68 The advantage of an international treaty over an informal agreement is that migration cooperation is not as dependent on fluctuating priorities and changing governments. This is evident in the context of Indian migration cooperation with the Gulf states: India has had better experience under its international migration agreement with Saudi Arabia than under the non-binding memorandums of understanding with other Gulf states such as Oman and Bahrain.69

Skilled Labour Strategy for India

Once the BMI and the AA had secured agreement on the MMPA, the entire German government was called upon to implement it. During the previous legislative period, the BMAS developed the political will to shape the cooperation on skilled labour recruitment from India; and in autumn 2024, it published, together with the AA, a corresponding strategy.70

The “Skilled Labour Strategy for India” focuses on the improved matching of Indian skilled workers with companies in Germany and on increased efforts to teach the German language in India, including through more online language courses. Economic and academic cooperation is to be expanded and partnerships with Indian institutions in the field of higher education and vocational training intensified. In addition, a series of measures are planned to promote targeted outreach and provide information on regular migration channels to Germany. They include further developing the “Make it in Germany” information portal so that it is more country-specific as well as working with Indian influencers on social media and making use of trade fairs in India.

The strategy also includes measures to improve the recognition of Indian professional qualifications (which was included in the MMPA) and streamline the administrative processes in Germany and abroad necessary for the migration of skilled workers. A new sub-working group has been set up to deal with labour migration issues separately from return policy. Although the strategy may be of shorter-term nature compared with the MMPA, it has effectively highlighted the potential of migration cooperation for both parties. Moreover, in this document, the enormous importance of private recruitment agencies is recognised for the first time and their regulation has been made an area of future cooperation.71

Legal framework and state actors

Following a reform in 2020, the Skilled Labour Immigration Act was amended in 2023, further opening up the already liberal legal framework for labour migration to Germany from third countries. As early as 2013, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) had stated that Germany had the most liberal immigration regulations for skilled workers and highly qualified people of all OECD member states.72 However, unlike in countries such as Italy and Spain, Germany’s migration law is not geared towards accepting large contingents of workers from abroad.73 For this reason, the MMPA does not set binding targets for labour migration or rules that favour Indian migrants. Rather, the agreement aims merely at interpreting the rules in the spirit of goodwill and strengthening and improving the conditions for cooperation between state actors from the two countries. For Germany, this means the continued presence of Goethe institutes and centres in India, while those facilities have recently been closed in other countries.74

Various ministries from each of the two countries have agreed to cooperate with one another. In Germany, the AA and the BMAS are playing a key role. The AA is responsible for coordinating specific measures in India through its country desk and missions abroad; and the BMAS is responsible for coordinating the measures in Germany outlined in the Skilled Labour Strategy for India and for dealing with specific issues related to labour migration. Other German ministries that have dealings with India are involved, too, through a new, interministerial country concept for the recruitment of skilled labour from India. They include the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWE), the Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR), the Ministry for Education, Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMBFSFJ), the Ministry of Health (BMG) and the Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Finally, the AA and BMAS are responsible for implementing the country concept, which, the first of its kind, is intended to ensure that the activities of the individual departments are coordinated on the ground.

In India, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), the Ministry of Labour and Employment (MOLE) and the Ministry for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) are responsible for migration cooperation with Germany. From 2004 to 2016, there was a separate Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs (MOIA), which was responsible for promoting labour migration and the Indian diaspora; for reasons of efficiency, it was later integrated into the Ministry of External Affairs.75 Responsibility for issues related to the return of nationals lies with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as in the case of Germany.

The respective embassies and implementing organisations of the two countries play a key role in migration cooperation, too. On the German side, they include the German Employment Agency (BA), the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the Goethe institutes and centres, and the Indo-German Chamber of Commerce (AHK). On the Indian side, the semi-state National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) has a special role to play. A public-private partnership (PPP) that is 51 per cent privately funded, the NSDC was established by the MSDE in 2008. Besides performing its main task of vocational training, the NSDC is also active in the training and recruitment of Indian migrant workers through its subsidiary NSDC International (NSDCI). But because the NSDCI does not have a licence as a recruitment agency, it has to depend on cooperation with licensed agencies.

In India, migration is only loosely regulated; attempts to reform migration legislation have failed.

In India, the regulation of migration is less developed than in Germany or even other leading countries of origin for migrant workers. Furthermore, the protection of Indian workers from exploitation and abuse has long been neglected. The employment of Indian nationals abroad is regulated by the Emigration Act of 1983.76 The Protector General of Emigrants (PGE) under the Ministry of External Affairs is responsible for implementing Indian migration legislation. Its most important task is to protect Indian migrant workers from exploitative or fraudulent recruitment practices. The PGE is supported by 14 regional sub-units, known as Protectors of Emigrants (PoEs), which act as licensing and supervisory bodies at the operational level. In early 2025, it was announced that the number of PoEs is to be increased to ensure better territorial coverage.77

One of the PGE’s main powers is to grant licences to recruitment agencies. At the same time, it has an oversight role and is responsible for ensuring that employment relationships are based on fair recruitment practices and binding contracts. (To this end, the eMigrate system was introduced in 2014. This is a digital platform that connects all relevant government agencies with potential employers, workers and insurance companies. It also enables affected migrants or third parties to report unregistered or fraudulent recruitment agencies.78) The PGE’s supervisory powers are limited by executive order to 18 target countries in Asia and the Gulf states – both regions where working conditions can be particularly precarious. Furthermore, checks are carried out only on employment contracts for low-skilled and selected medium-skilled jobs. Highly skilled workers and students, along with migrants to Western countries such as Germany, are exempt from state control and approval procedures.

In 2021, an attempt to reform India’s outdated migration legislation proved unsuccessful.79 However, the growing number of abusive recruitment practices – including those that may have been deployed in the case of the Indian migrants who claim to have been unwittingly recruited as mercenaries for the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine – has triggered new dynamics.80 The Indian government is reportedly planning to introduce a new bill to the parliament in 2025 – an Overseas Mobility Facilitation and Welfare Bill.81 Meanwhile, the Immigration and Foreigners Bill82 was passed in spring 2025 as a replacement for the outdated law on the entry, stay and departure of foreigners in India. Under the new law, a modern, digitally supported system is to be introduced – one that includes a visa and registration requirement and the establishment of an immigration authority.

The Indian states attach great importance to migration cooperation, although there is no mention in the MMPA of such cooperation at the state level.83 They pursue their migration policy interests more or less independently of the Indian central government, and almost half of them have their own semi-state recruitment agencies. At the same time, there have been new regulatory attempts at the level of the states to prevent abusive recruitment practices. In the southern state of Kerala, for example, a task force headed by the local PoE has been formed,84 which, among other things, launched investigations against numerous fraudulent recruitment agencies in March 2025.85

Non-state recruitment actors

Non-state actors play a crucial role in self-organised migration from India to Germany. They include the Indian migrant workers themselves, who often use their networks and knowledge of the local language and conditions to inform and support people in India who are interested in migrating. The importance of these diaspora actors is recognised in the MMPA (Article 11) and promoted within the framework of the GIZ programme “Migration & Diaspora”.86 Otherwise, there is no mention in the MMPA of non-state actors.

The Indian staffing and recuitment market is lucrative: it was estimated to be worth US$18 billion in 2022 and projected to reach around US$48.5 billion by 2030.87 Private recruitment agencies operate in complex networks involving employers, private universities and other agencies both within India and elsewhere.

Many private recruitment agencies are not registered, making it even more difficult to regulate them.

Just under 2,000 recruitment agencies are registered with the Indian Ministry of External Affairs. All are required to provide a bank guarantee: agencies that place fewer than 100 workers a year have to deposit the equivalent of around €8,000, while the others have to deposit the equivalent of some €50,000.88 Because even the lower amount can be too high a hurdle for smaller recruitment agencies, it is not surprising that there is a large number of unregistered providers – more than 3,000 according to a 2024 parliamentary report – whose activities are rarely prosecuted.89 It is often private recruitment agencies working in the field of education migration90 and travel agencies that operate outside the existing regulatory framework, as they are not required to register with the Indian Ministry of External Affairs and thus their activities are not monitored.91

Excessive recruitment fees for prospective migrants is a common problem.92 Although there is an upper limit of 30,000 Indian rupees (around €300) plus 18 per cent VAT,93 many migrants have to pay up to US$1,500 for a job in the Gulf states.94 Higher four-digit euro amounts are demanded for migration to Europe, with placements in East European countries such as Romania or Hungary tending to be cheaper than in those in Germany.95

Though not explicitly stated in law, registration is, in effect, limited to Indian nationals or Indian-registered legal entities. This is the reason why the AHK-India was denied a recruitment licence, for which it had applied as part of the BMWE-funded pilot project “Hand in Hand for International Talents”: the implementation of the project, aimed at the recruitment of skilled workers in the catering industry,96 required partnering with a registered Indian recruitment agency. For international recruitment agencies, another option would be to establish an Indian subsidiary run by a local manager.

Alongside the traditional German recruitment agencies, new actors are to be found along the German-Indian migration corridor. They include IndiaWorks97 in Freiburg, which is jointly operated by a former employee of the local chamber of crafts and a representative of the Indian recruitment agency Magic Billion. IndiaWorks recruits workers for the hospitality, skilled trades and healthcare sectors. While skilled workers are placed free of charge (according to the “employer pays principle”98), trainee apprentices have to pay fees totalling several thousand euros for their preparation, language training and placement, in part as employers are unwilling to contribute to those costs because they will have to provide expensive training once the trainees are in Germany.99 From an Indian perspective, the earning potential in apprenticeship professions in Germany seems to be attractive enough that even people with an Indian bachelor’s degree are being recruited for training positions.100 When approaching employers, it is advantageous to have legal representation and local contacts in Germany – something that Indian recruitment agencies have recognised, too. This explains why Indian companies are taking over German nursing recruitment agencies. For example, Border Plus has acquired the Onea Care recruitment agency101 and TERN the Rekruut company.102 Both German-based companies are certified with the quality seal “Fair Recruitment Healthcare Germany”, which, introduced by the BMG, is intended to guarantee, among other things, the “employer pays principle” and comprehensive integration support.103

Despite the growing number of private recruitment agencies active along the Indo-German migration corridor, there is still no systematic oversight and control over their practices. To ensure fair migration, bilateral migration cooperation should be aimed at strengthening the transparency and regulation of private recruitment agencies.

Migration Cooperation: Opportunities and Challenges

In general, increasing migration from India is viewed positively in Germany, as it helps alleviate the shortage of skilled workers and because there are only a small number of Indian nationals residing irregularly in Germany, even though the overall number of Indian migrants is rising. At the same time, interest in Germany as a migration destination continues to grow in India.104 However, while many opportunities exist for expanding labour and education migration from India to Germany, there are also challenges. These include the different approaches to migration cooperation, skills matching in the area of labour migration and quality control in the selection of Indian students. Furthermore, India’s cooperation over the return of citizens required to leave Germany will remain a thorny issue, even though the numbers of such individuals are relatively low.

Different approaches to migration cooperation

India has extensive experience in migration cooperation with a large number of destination countries. It has concluded legally binding and non-binding agreements with seven European countries (including Germany, France and the United Kingdom) and other destination countries such as Australia, Jordan, Israel, Japan, Taiwan and the Gulf states.105 Migration cooperation clearly contributes to the diversification of India’s foreign policy relations, as it can serve as unifying element that strengthens cooperation in other areas. The Indian government sees at least some parts of the diaspora as representatives of its interests abroad.106

Another important incentive for the Indian government is remittances, which have more than doubled since 2010 and were estimated to reach around US$129 billion, approximately 3.4 per cent of gross domestic product, in 2024.107 Some regions of India depend heavily on remittances, which are crucial for their economic development. In recent years, the share of remittances from industrialised countries has risen significantly, overtaking those from the Gulf states.108 In addition to the tangible financial gains, India is counting on the intangible benefits: namely, that at least some students and workers from abroad will return to India with language skills, professional knowledge and entrepreneurial skills that can contribute to the country’s economic development.

Yet another incentive is linked to the immense challenges facing India’s labour market and education system. Around 90 per cent of the workforce is employed in the informal sector, and many people remain dependent on very low-paid casual work.109 In order to offer the growing working-age population the prospect of employment, between 60 million and 150 million new jobs will have to be created by 2030.110 But for decades, the Indian education system has favoured an elite higher education system over a high-quality broad-based one, which has had negative consequences for social justice and the long-term development of the Indian economy.111 Even if these structural deficits were to be tackled immediately, the tangible benefits could be expected only in the medium term. In the meantime, migration is helping alleviate at least some of the pressure on the job market.

For the Indian government, migration agreements provide an opportunity to reform vocational training. As a reference model, it cites the Technical Intern Training Programme (TITP) – an exchange programme with Japan that was launched by the MSDE in 2017 and is being implemented by the NSDC. The aim of the programme is to allow young Indians to acquire vocational qualifications through practical training at Japanese companies. However, the impact has been limited so far: by March 2024, the number of participants had only slightly exceeded 1,000.112 While India’s interest in practical training and knowledge transfer is understandable, such programmes could not easily be transferred to Germany because they would be at odds with German immigration law. Moreover, they run counter to the interests of German employers, who are keen to retain skilled workers once they have invested in their training.

The different approaches to migration cooperation are also evident in debate about the number of Indian migrants making their way to Germany. In 2024, the Indian government criticised the German implementation of the MMPA as too hesitant, noting that the MMPA target of recruiting 3,000 young workers a year (Article 6) had not been met through state-supported recruitment programmes. In response, Germany pointed out that significantly more than 3,000 had been recruited thanks to self-organised migration and that this figure was in any case not intended to be achieved exclusively through state-supported recruitment programmes.113

Although this dispute has now been resolved, it highlights the fundamental differences in approaches towards migration cooperation. While the Indian government is pushing for a rapid scaling up of labour migration through state recruitment programmes, there remains uncertainty in Germany as to which Indian state actor can be considered a trustworthy cooperation partner. The NSDC recently came under heavy criticism over a recruitment agreement concluded with Israel in November 2023 following the sudden shortfall of Palestinian workers in the wake of the Hamas attack. The Indian workers sent to Israel did not receive sufficient information or protection, nor were they sufficiently qualified in the eyes of their Israeli employers.114 Even better-prepared, privately recruited Indians suffered as a result of the poor reputation of Indian workers that the NSDC initiative generated.115 In addition to this problematic track record, there were also allegations of corruption made against the NSDC in spring 2025. They led to the dismissal of the chief executive officer, who simultaneously served as managing director of the NSDCI (the subsidiary created for recruitment).116

Against this backdrop, it is to Germany’s advantage that it is already cooperating with individual Indian states to recruit skilled workers. For example, under the “Triple Win” programme implemented by the BA and GIZ to attract nursing staff, recruitment agreements were concluded with the semi-state recruitment agencies Norka Roots in Kerala (end of 2021) and TOMCOM in Telangana (end of 2023).117 For their part, the German states have launched their own recruitment measures together with various Indian states; some of which are linked to existing university partnerships or India-based liaison offices for economic cooperation.

The conditions for cooperation vary considerably from Indian state to state, above all owing to the diverse migration traditions.118 In terms of the volume of international remittances, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh are the most important home states of Indian migrants.119 However, there are significant differences in conditions even within each of these states – for example, between urban and rural areas. Good educational standards and a reliable migration infrastructure are important factors for cooperation. The economy and social fabric of Kerala, for example, has been shaped by migration since the 1970s. It has two well-functioning semi-state recruitment agencies: Norka Roots, which offers comprehensive support and reintegration services for migrants from Kerala, and ODEPC Kerala, whose sole focus is recruitment.

Many other states do not have such high-quality recruitment structures. They include Maharashtra, notwithstanding the large volume of remittances that it receives. In early 2024, Baden-Württemberg signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the state on the recruitment of a sizeable number of migrant workers.120 For its part, Maharashtra – during the run-up to the State Assembly election – took steps to rapidly set up a new state recruitment agency and other support structures, including language training in cooperation with the Goethe Institute. But then it rushed ahead with the selection of several thousand candidates, despite not yet having agreed on the selection criteria with the German state of Baden-Württemberg, which was not responsive to attempts to forge ahead with the project.121 Both sides seemed to have lacked the experience and state structures to implement the MoU, which might have been signed primarily for political purposes. As a result, the project is currently on hold, causing enormous disappointment among the candidates selected in India.122 This whole episode underscores the need for robust implementation structures as well as for expertise on both sides in launching such projects.

In any case, private recruitment agencies are often able to support migration ambitions more effectively and flexibly as many have a long track record in the selection of good prospective migrant workers and the necessary job-specific preparation. However, the quality of services offered varies enormously: while some established recruitment agencies have been operating reputable businesses for many years, others lure potential clients with unrealistic promises or even fraudulent claims. Moreover, the vast majority of the agencies charge their clients fees, thereby violating the “employer pays principle”. Improved regulation of private recruitment agencies is essential for the sustainable expansion of labour migration from India. Because Germany cannot directly regulate India-based agencies, it is required under the framework of the MMPA to engage in closer bilateral coordination with the Indian government and the individual states from which the majority of labour migrants to Germany are recruited.

Skills matching for labour migration

Since the early 2010s, migration from India to Germany has increased significantly, mainly owing to highly skilled workers gaining access to the German labour market via the EU Blue Card. These skilled workers make an important contribution to alleviating skilled-labour shortages, particularly in key sectors such as IT. Overall, their integration into the German labour market has been very successful: in February 2024, the unemployment rate among Indian nationals was just 3.7 per cent, roughly half the German average. In addition, Indian workers tend to be younger and better educated than the average member of the working population in Germany and are more likely to be employed in highly skilled professions, especially the STEM ones. A similar trend is evident in income levels: at the end of 2023, the average gross wage of Indian nationals was €5,359, well above the German median of €3,945.123

At the same time, there are signs that the proportion of IT experts among migrants to Germany is declining, although it is not entirely clear why. One reason could be Germany’s weak economic growth in recent years and the corresponding fall in demand for workers in the local IT sector. Another could be the declining attractiveness for IT specialists from India, because they are also in demand in their home country and earning opportunities have improved. What is certain, however, is that demand for Indian experts in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) is growing.124

Unclear is which fields of activity beyond the STEM professions lend themselves to recruitment from India.

It remains to be seen whether Indian specialists beyond the STEM and AI professions can be successfully recruited for those industries where the shortage of skilled workers is greatest. Small and medium-sized enterprises, in particular, remain reluctant to recruit workers from third countries such as India. According to a survey conducted on behalf of the Bertelsmann Foundation in 2024, only 18 per cent of German firms were actively seeking workers abroad, even though a full 70 per cent of the companies surveyed complained about staff shortages, especially among those with vocational training.125 The high administrative hurdles, including the lengthy recognition of professional qualifications, are often cited as the reason for their reluctance. However, another factor is scepticism about the integration and performance capabilities of third-country nationals. For their part, Indians interested in migration are often very concerned about discrimination and racism in Germany. According to an OECD survey of skilled workers of various nationalities who have migrated to Germany, this has proved to be a much bigger problem than anticipated by those workers.126

Besides the social challenges, successful labour migration requires an effective matching process to ensure that Indian qualifications are transferable. The fact that practical training accounts for only a small proportion of the Indian curriculum is considered a weakness compared with the German dual system of vocational schools and training on the job. Nevertheless, there appears to be a good match in the healthcare professions, particularly in the case of urgently needed nursing staff. Their training is regulated at the federal level by the Indian Nursing Council and in many respects meets the requirements for nursing professionals in Germany127 – a strength that the GIZ project “Global Skills Partnerships”, funded by the BMG, wants to further enhance. As part of this project, German and Indian education institutions are developing joint nursing curricula. The aim is to ensure that the corresponding qualifications can be immediately recognised in either country.128

Discussions are also under way on the targeted recruitment of workers in other sectors, including for so-called green jobs (for example, technicians and engineers for renewable energies). In addition, Deutsche Bahn (DB) plans to recruit Indian train drivers and, in the long term, train skilled workers in India for other occupations within the company.129 As regards other occupational fields, pioneering work will be necessary in both Germany and India, involving cooperation between government actors, companies and private recruitment agencies.

Besides government pilot projects aimed at attracting skilled workers for specific industries, the effects of the newly established legal avenues for self-organised labour migration to Germany should be closely monitored. The Opportunity Card introduced in Germany in summer 2024 is intended to enable qualified individuals to find a job in Germany and gain a foothold in the labour market. Those who already have a residence permit for employment or training can apply for the card, too. During the job search, part-time work (up to 20 hours a week) is permitted. Although it is still too early to draw any meaningful conclusions, it seems that private recruitment agencies regard the Opportunity Card as a relatively simple migration route from India.130 It remains unclear how many Indian migrant workers have, in fact, entered the country in possession of this new residence permit and whether they are sufficiently informed about its initial temporary nature.

Education migration – High level of interest demands improved selection procedures

An important driver of Indian migration is the desire to study abroad. In 2024, there were 1.33 million Indian students enrolled in other countries,131 most of whom came from the states of Maharashtra, Telangana and Punjab.132 Germany ranks fifth among the most popular destination countries and is the leading non-English-speaking country for study, accounting for around 6 per cent of all Indian students enrolled overseas.133 The fact that there are no or only low tuition fees at Germany’s institutes of higher education134 makes the country attractive to students from India’s middle class who want to avoid the high fees charged by traditional destination countries.135

Germany has less experience dealing with international students than traditional immigration countries such as Canada and Australia.136 Standardised selection procedures abroad have barely been established, not least because German universities are less market-oriented and therefore less active in seeking to recruit students from abroad.

The majority of Indian students in Germany have already obtained a bachelor’s degree in India and are now pursuing a master’s degree in Germany (mainly through courses offered in the English language). Only 10 per cent come to Germany to study for a bachelor’s degree.137 This is due in part to the fact that there is only a limited number of good study programmes beyond the bachelor’s level in India. Seventy-three per cent of Indian students in Germany choose a STEM subject, which corresponds to the prevailing educational preferences in India.138 According to the OECD, the proportion of Indian students who remain in Germany after the completion of their studies is higher than that among students of other nationalities. In 2020, 76 per cent of students who had gone to Germany from India five years earlier were still in the country after graduation, compared with an average of 63 per cent of all international students.139 A DAAD survey conducted in 2024 confirms the higher number of students intending to stay: around 40 per cent of Indian students said they were “definitely” planning to remain in Germany, while another 26 per cent said “probably yes”.140

Amid the growing number of Indian students wanting to study in Germany, the country’s higher education system is faced with the challenge of selecting the right candidates from among the numerous applications. Under the German-Indian MMPA, an Academic Evaluation Centre (APS) was established at the German Embassy in New Delhi (as had been done previously at the German embassies in China and Vietnam) “to improve the quality of applications of qualified Indian students as well as the application process experience for the applicants”.141 However, the APS in India has so far limited itself mainly to supporting visa procedures and checking the admission requirements of Indian students. It is clear that the role the APS could play goes beyond this. An internal evaluation of APS data shows that it is not always the best-performing students from India who apply to study in Germany. Moreover, there are hardly any students from India’s leading universities among the applicants.142

Owing to the admission freeze for international students in the United States and the more difficult visa and admission requirements in traditional destination countries such as the United Kingdom and Canada, interest in studying in Germany will only continue to grow.143 As in the case of labour migration, private agencies play a key role here. They provide support with the choice of university as well as with the application and visa process; and they also offer their services to foreign universities.144 However, they are not regulated by the responsible authorities (PoEs), which makes it difficult for the Indian state to clamp down on fraudulent activities.

Finally, professional education consultancies face the challenge of “study-abroad influencers”, who share their experiences in Germany over social media and YouTube.145

Indian students in Germany suffer under the questionable practices of some recruitment agencies.

The growing number of Indian students is having a direct impact on the German labour market, as many have part-time jobs in the gig economy and logistics.146 Many Indian students have to generate an income while studying – mainly through temporary jobs in services such as food delivery – in order to pay off the debts they incurred when migrating to Germany.147 At the same time, they face high rents and precarious living conditions and have to do everything in their power to protect their residence status.

Together with some private universities, private recruitment agencies have developed a business model in which they secure places at university for young Indians and then charge them a high four-digit sum in euros annually. These private universities offer a quality of education that is not always the highest and award degrees that are often not recognised by the German authorities, leaving graduates with poor prospects of finding employment in Germany.148 Such abusive practices among international educational institutions, which are still only a limited phenomenon at present, should be curbed by the responsible bodies in Germany. If they are not, the credibility of the entire migration corridor is at risk, as demonstrated by the example of Canada, where similar cases of fraud led to a tightening of migration policy.

Fortunately, most Indian students in Germany attend regular universities. Despite all the challenges, there is enormous potential for their helping alleviate pressure on the local labour market. This potential could be tapped into more effectively if local networks of universities, civil society and employers were involved in language support and integration measures from the outset. For its part, the German Employment Agency is seeking to lead the way with a pilot project to support Indian students in selected locations as they transition to the labour market.149

Return policy – (not) a major problem

Compared with the total number of Indian nationals residing in Germany, the number of those required to leave the country is very low. Nevertheless, improved readmission cooperation was the guiding principle for the German government and the BMI (the responsible ministry for this issue) during the bilateral negotiations in 2018. But it should be noted that the relatively high number of asylum applications at the time (2016) – some 3,500 – may have been a factor.

After the conclusion of the MMPA, there was criticism from within the German government about readmission cooperation having, in fact, declined rather than improved. In 2023, 51 Indian nationals were returned,150 compared with 176 in the pre-coronavirus year of 2019.151 The reasons for this are not clear. The lower number of repatriations could be interpreted as a tactical move by an Indian government that wants to see immediate tangible progress in the expansion of labour migration to Germany. However, it seems more plausible that time was needed for adjustments to be made on both sides following the replacement of the previous voluntary repatriation practice by a formal agreement. Indeed, repatriation processes depend to a large extent on trust being built between the administrations and individual actors involved and the resulting willingness to cooperate.152

The return of persons required to leave the country is regulated by Article 12 of the German-Indian MMPA.153 Accordingly, India is obliged to respond to a readmission request within 30 calendar days if the identity of the person to be returned has been clearly established. If this is not the case, the deadline does not apply and India has the option to confirm the Indian nationality of the individual concerned “within a reasonable period”. That process requires lengthy checks because the Indian side often insists on the nationality being confirmed by the police of the responsible state.154 Once people have been returned or return voluntarily, they find themselves with almost no support from the Indian state: there are no reintegration measures in place apart from those supported by Germany for voluntary returns (such as the REAG/GARP programme155), as a report to the Indian parliament pointed out.156

Recently, the number of returns of Indian nationals required to leave Germany has risen again: in 2024, they more than tripled compared with the previous year. A total of 167 Indian nationals required to leave were deported,157 while 656 returned voluntarily.158

Cooperation on readmission can be expected to continue to improve. At the same time, the new German government wants to declare India a safe country of origin in order to speed up decisions on asylum applications received from that country. Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland, France and Switzerland have all classified India as a safe country of origin.159 At the end of 2024, the Netherlands however had to remove India from its list of safe countries of origin in accordance with a ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that countries cannot be classified as safe when certain regions are excluded.160 In April 2025, the EU Commission proposed a uniform application of the concept of “safe country of origin” in the form of a new, joint EU list and named India as one of the countries that might be included on that list.161 Even if asylum applications and the return of Indian nationals required to leave the country remain issues for bilateral migration cooperation, other challenges appear more urgent.

Enhancing Germany’s External Infrastructure in India

Improvement of Germany’s external infrastructure

In order to attract suitable workers from India, Germany must further develop its external infrastructure. The German Foreign Office has acknowledged this in recent years by expanding the relevant personnel capacities of embassies and consulates and maintaining the presence of the Goethe Institute.162 There have also been major improvements in visa procedures. The diplomatic missions in India are playing a pioneering role here. With the support of external service providers and the German Office for Foreign Affairs (BfAA), the time needed for the acceptance and processing of applications has been significantly reduced. Since 2022, the German Consulate General in Kolkata has been running a pilot project to test the digitisation of visa procedures, which should become standard practice at all missions abroad. The goal is for applicants to appear in person only for identity checks and biometric data collection, with everything else – at least in the case of India – being done electronically in advance with the help of external service providers. Even if there are concerns among domestic policymakers that such services are very vulnerable to fraud, the increasing number of visa applications in India would virtually be impossible to handle without VFS Global.

The so-called Work and Stay Agency for the recruitment of skilled workers, which is envisaged in the German coalition agreement of April 2025, will probably build on the experience gained from digitisation and centralisation. At the same time, the new German government will be able to assess the impact of the latest amendments to the Skilled Labour Immigration Act with the benefit of hindsight.

Furthermore, it is important that Germany’s external infrastructure in India is kept up to date in order to reach and inform Indians interested in migration. To this end, the central online portal “Make it in Germany” should be further developed and supplemented with a country-specific section.163 Any revisions of the platform should consider further simplifying the language, as the English used may be too complicated for non-native speakers, and translating the information provided into the most relevant other languages of India. Indian influencers in Germany, such as Foreign Ki Duniya,164 play an important role in providing information, too. However, a critical assessment is needed here as there are numerous reports of influencers painting an unrealistic picture or pursuing fraudulent business models.

The provision of a sufficient number of high-standard German-language courses is a major challenge for German institutions abroad.

Ensuring adequate capacity for the teaching of the German language is a considerable challenge for German institutions in India. In what is a rapidly growing market, the quality standards of the numerous private-language schools vary significantly. This is evident from the significantly lower pass rates in Goethe Institute language exams among those who have attended courses at alternative (mostly cheaper) providers, which often fail to ensure the same level of language proficiency.165 It is in this environment that the Goethe institutes and centres have to compete. Other institutions that certify the level of German-language skills include telc, a subsidiary of the German Adult Education Association,166 and the Austrian German-Language Diploma (ÖSD).167 At the same time, there are enormous differences in the approaches to language teaching. Some private agencies offer fast-track courses in which Indians interested in migration are prepared for the B1 level examination in two to three months of full-time study at boarding school-like structures.168 Given the increasing number of certification bodies and the growing range of courses on offer, it is essential to define quality standards and systematically monitor compliance with them.169

The growing interest in learning the German language is also evident from the number of students learning the language within the Indian education system. In 2024, there were 18,144 students studying German at 48 PASCH schools,170 25,704 at 126 schools participating in the Deutsch an 1000 Schulen project and 81,605 students at 413 other secondary schools.171 Between 2011 and 2014, a more systematic approach had been pursued by the Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan (KVS) – a central government organisation that runs more than 1,200 schools throughout the country and, above all, provides educational continuity through a uniform curriculum for the children of civil servants – which integrated German-language instruction into its syllabus. However, after just three years, German was struck from the curriculum as a result of the nationalist language policy pursued by the Indian government.172

Under the National Education Policy, which was reformed in 2020, students are required to learn three languages, one of which may be a non-Indian one; this means that German can be offered as a third language only if a state decides accordingly. For its part, the German Foreign Office has said there is reason for “cautious optimism” over the impact of this policy.173 For example, from the 2026–27 school year, the state of Maharashtra plans to introduce 12 non-Indian foreign languages – including German – for Grades 8 to 10 and possibly Grade 11 to 12. In order to further strengthen the status of German as a foreign language within the Indian education system, including at universities, new measures should be promoted within the framework of migration cooperation.

In order to improve the management of student migration from India, the APS should be granted increased responsibilities so that, among other things, a more competitive selection of study applications could be established in cooperation with the DAAD and German universities. To this end, the German government should seek a dialogue with the German states and universities aimed at reforming the admission procedures for international students. Measures should also be taken to increase the proportion of Indians studying for a bachelor’s degree in Germany, as receiving a full higher education increases the likelihood of language acquisition and retention.

Redefining migration-related development cooperation with India

Although the BMZ has focused on migration-related development cooperation for several years now, the topic has barely been addressed in Germany’s development cooperation with India. For example, Germany does not have a Centre for Migration and Development in India, even though the establishment of such centres has been a flagship initiative in recent years.174 The only related undertaking that the BMZ has supported is the much smaller “Shaping Development-oriented Migration” (MEG) project. Launched by GIZ, MEG involves 15 partner countries in all, one of which is India.175

For a long time, there were no links within the BMZ’s bilateral portfolio to other development cooperation priorities with India. It was only at the request of the Indian government that a migration component was added to an already planned GIZ project to improve vocational training in green professions, especially for women.176 Under this project, curricula are to be designed in such a way that trainees also qualify for employment in Germany or other destination countries. However, this should be seen only as a start. Together with the BMBFSFJ, the BMZ is working with India’s MSDE to make the Indian vocational training system more practice-oriented.177 And in spring 2025, the Indian government signalled in the JWG sub-working group on labour migration that it wants the state vocational training centres to be more geared towards practical preparation for working in Germany and to offer language courses.178

The BMZ’s hesitance can be attributed, among other things, to the strict limits on the use of development funds set by the OECD Official Development Assistance (ODA) criteria.179 According to these criteria, no activities may be supported if German employers are likely to benefit more than the country of origin – in this case, India. In addition, there may be concerns that the recruitment of skilled workers by German companies could lead to a brain drain of highly qualified workers in India. Indeed, there are labour shortages in those sectors in India – such as IT, renewable energies, electromobility, healthcare and manufacturing – in which modern technologies require rapid skills adjustments. And workers who have undergone practical training are in short supply, too, particularly in the technical professions and those requiring digital skills.180 As for shortages in the health and care sectors, these are evident mainly in the poorer, rural states.181 However, the main reason for this is not migration but inequalities within the country and the fundamental inability to exploit the country’s demographic potential and ensure that the several million workers who join the workforce each year have sufficient employment prospects.

Moreover, recent migration research highlights the many benefits of migration for the development of countries of origin. Besides the positive impact of remittances, they include strengthening educational incentives in the country of origin. Furthermore, some migrants do return to or invest in their home country – a phenomenon known as “brain circulation”. In India, this effect was particularly evident in the rise of the IT sector: influenced by their experiences in Silicon Valley, members of the Indian diaspora in the US brought technical know-how, market knowledge and international business practices back to India, thereby making a significant contribution to the global competitiveness of the Indian tech industry.182

So far, “Triple Win” has been the only recruitment project launched by a development cooperation actor. It is funded not by the BMZ but by German employers and is being implemented by GIZ International Services, a subsidiary that is allowed to generate revenue, which it reinvests into its development projects.183 GIZ International Services is supporting the recruitment agreement between the German Employment Agency and the semi-state recruitment agencies of the states of Kerala (since 2022) and Telangana (since 2024). The advantage of these programmes is that they are based on international standards for fair recruitment, including the “employer pays principle”. However, only 670 nursing staff have been recruited in three years; all of them were from Kerala.184 More recently, the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations (BDA) called for the “Triple Win” programme to be phased out, arguing that it was not attracting enough skilled workers and that private agencies had long since become more important.185 It is difficult to make an empirical assessment of the claim by the BA (which is also involved in “Triple Win”) that the programme is a trailblazer for other recruitment agencies and that, in the best case scenario, the latter would be guided by the same principles of fair and orderly labour migration going forward.186

Given India’s strategic importance both as a partner country for development cooperation and as an important country of origin for labour and education migration, the BMZ should seek to develop new measures and, together with the BMAS, step up the promotion of the framework conditions for fair migration to Germany. An important step in this direction is the decision to put private recruitment agencies to the agenda of the MMPA Joint Working Group (the sub-working group on labour migration), which is in line with the Skilled Labour Strategy for India. In addition, the German government should encourage the Indian government to improve the regulation of private agencies recruiting workers for Europe – for example, through the Protector General of Emigrants and the eMigrate platform – as a part of a possible reform of Indian migration law. Alternatively, a list of trustworthy recruitment agencies could be drawn up with the Indian government or dialogue sought with the various associations of private recruitment agencies with a view to establishing voluntary commitments along the German-Indian migration corridor.

It is unclear whether the German concept of fair migration is compatible with the reality of the Indian migration landscape.