Security Politics “from Below”

Why the OSCE Should Systematically Incorporate Civil Society Expertise and Engagement to Remain Relevant in Matters of Peace and Security

SWP Comment 2025/C 35, 30.07.2025, 7 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2025C35

Research AreasIn the 50th year of its existence, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is more than ever looking for a new role. The war in Ukraine and other conflicts in the OSCE area show how important the work of civil society organisations is in times of war and crisis – especially in fields where the state’s ability to act is limited. In an increasingly fragile international order, the OSCE should refocus on its strengths in regional conflict management and take greater account of the expertise of civil society. Moreover, representatives of civil society should get involved in the structures of the OSCE more systematically than has been the case to date, not only formally but also in practice. The Helsinki Conference on 31 July 2025, which commemorates the adoption of the CSCE Final Act, offers a good starting point.

This year’s Finnish Chairperson of the OSCE has set the commitment to a free civil society as one of its priorities. Strengthening civil society and cooperating with it has always been of particular importance to the OSCE. The Helsinki Accords of 1975 not only laid the foundation for the emerging security dialogue in the East-West conflict, but also for a broad movement of human rights and civil society organisations in East and West. Citizens joined forces in so-called Helsinki Committees. They advised their governments on the implementation of the Helsinki principles and also committed them to the Helsinki model as an agenda for peace and disarmament, with the purpose of holding them accountable.

However, in times of geopolitical upheaval and the resurgence of Realpolitik notions of power and strength in international relations, civil society finds itself in a difficult position, especially as it tends to argue on the basis of moral convictions and represent values in a more idealistic way. States are also increasingly unwilling to fulfil their obligations in terms of (military) transparency and accountability (towards society).

And yet the war in Ukraine shows just how important the work of civil society organisations is in times like these – not necessarily in the traditional sense of promoting peace, but as a compensatory force in areas where the state’s ability to act is limited. Civil society engagement will foreseeably become even more important in a potential post-war phase. This applies not only to Ukraine, but also to other conflicts in the OSCE area where the OSCE could be mandated by the parties to the conflict and participating States to implement decisions (e.g. in the implementation of a possible peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan). In the rehabilitation phase, civil society actors can make important contributions, for example in the areas of border security and border management (delimitation / demarcation) or humanitarian demining.

The OSCE distinguishes between three dimensions in its work: the politico-military, economic and environmental, and human dimensions. In the 1990s, the model of the so-called conflict cycle was developed as an instrument of the politico-military dimension, in which the four individual phases of conflict – early warning, conflict prevention and resolution, crisis management and post-conflict rehabilitation – entail cross-dimensional elements.

In dealing with current challenges, especially at the regional level, the OSCE should make even greater use of the potential of civil society expertise and cooperation. In the case of political deadlocks in particular, civil society actors can often make concrete proposals for improving the living conditions of people on the ground. However, more intensive involvement at the level of field operations would have to go hand in hand with greater consideration of security policy demands, interests and needs “from below” in the institutional structure of the OSCE.

Civil society in transition

Pressure on civil societies is growing. Their scope for action and the space for dissent and criticism are increasingly narrowing. Across Europe, funding for non-state actors is becoming more difficult due to tightening public budgets. Governments and OSCE institutions, on the other hand, underestimate the power and relevance of the tasks that civil society forces are capable of performing, including in security-related areas.

The OSCE itself does not have a narrowly defined concept of civil society. Traditionally, it has pursued a non-discriminatory approach in order to be flexible enough to accommodate the views and proposals of a broad spectrum of organisations in the OSCE area. However, it can no longer be taken for granted that civil society forces “east and west of Vienna” support the Helsinki Consensus. The so-called “non-civil” or illiberal civil society, which has recently been gaining momentum in Western liberal democracies as well, makes the call for “more” civil society engagement a somewhat ambivalent undertaking. However, there are certainly efforts to counter the influence of GONGOs (government-organised non-governmental organisations) within the organisation, and thus to counteract the instrumentalisation of the OSCE by authoritarian governments.

The relevance of civil society is often still limited to its role as an informant, a mouthpiece for citizens and a service provider. In the OSCE context, civil society is mostly heard in the third, human dimension. However, representatives of the Civic Solidarity Platform (CSP), a network of civil society organisations in the OSCE that exists since 2010, criticise the missing link between the first and third dimensions. They argue that there is still an “invisible wall” that reduces the engagement of part of the NGO community (especially activists and grassroots organisations) to the human dimension. Think tanks and academic institutions are predominantly invited to discussions and meetings of the Forum for Security Co-operation (FSC). This no longer lives up to the changing international threat context (which is characterised by cyber and hybrid attacks, disinformation and GONGO propaganda) and a civil society that is specialising accordingly.

In 2023, at least the CSP’s demands for a coordinator for cooperation with civil society were met and a corresponding position was created. Anu Juvonen, director of the NGO “Demo Finland”, was appointed the OSCE’s third Special Representative for Civil Society in 2025. She has set herself the goal of bringing civil society concerns into the organisation more efficiently. Since OSCE decisions are not legally binding and there are no reporting mechanisms or formal appeal procedures, Juvonen sees the watchdog role of civil society – i.e. to monitor both the policies of participating States and OSCE institutions – as paramount.

In the OSCE context, there are several categories of organisations that could continue to play an important role in the future due to their function: Firstly, the actors at the local level who are deeply rooted in their respective societies (women’s, human rights and victim protection organisations, as well as watchdogs that monitor government action). Secondly, the international humanitarian organisations that act in an advisory capacity but are also entrusted with implementation tasks (for example in the areas of civil protection, reconstruction, mine clearance, etc.). Finally, the civil rights and human rights associations that are committed to transnational advocacy work in the OSCE area and have, for example, joined forces under the umbrella of the aforementioned CSP to promote the preservation and implementation of the Helsinki Principles. Ultimately, these organisations, primarily NGOs, have no democratic legitimacy and are not subject to regular evaluation. They derive their mandate and legitimacy primarily from their commitment, their self-imposed obligations and the important functions they perform.

Conflict cycle and civil society

To this day, the relevant literature criticises the fact that civil society’s potential in the OSCE’s conflict work remains insufficiently tapped.

This finding is often linked to calls for a better integration of civil society. However, conflict contexts vary. In many cases, the parties to the conflict simply do not want civil society to be involved in official negotiations, blocking better integration. And yet the results of the research project on which this analysis is based show that civil society organisations in the OSCE area are still not sufficiently recognised, especially in the phases of conflict prevention and post-conflict rehabilitation. This is more crucial today, particularly as the active war / conflict phase is increasingly merging with the post-conflict rehabilitation phase. For example, reconstruction and humanitarian demining often begin during the ongoing conflict / war, as the Ukrainian case shows.

Conflict prevention

Conflict prevention is a low-visibility activity, and because there are few success stories, it lacks recognition. Within the OSCE, there have been calls for some time to explore new ways of better integrating the expertise of civil society organisations in the field of conflict prevention and early warning (e.g. their knowledge of local discourses, troop deployments on the ground, etc.). Ultimately, the international community could save enormous sums of money if it focused its efforts more specifically on preventing violence and conflict rather than on subsequent interventions to end them. Civil society organisations could provide valuable advice and support in this regard. Examples of civil society networks that provide advice on early warning and prevention can be found in a number of regional organisations, including the African Union.

Conflict management

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine highlights how important it is, in terms of the conflict cycle approach, to also consider the phase “under wartime conditions”. The OSCE no longer plays a significant role in Ukraine in the current phase, after the Special Monitoring Mission (SMM), established in 2014, was withdrawn following Russia’s full-scale invasion in spring 2022 and the Office of the Project Coordinator had to close. Although the OSCE subsequently set up an extra-budgetary support programme for Ukraine, this cannot fill the gap in conflict management. The Ukrainian government cannot compensate for everything either. The involvement of local civil society in cooperation with international humanitarian actors and other societal groups is therefore indispensable. Under wartime conditions, civil society activities aimed at building civil defence and resilience are essential. The military also relies on the help of civil society. Civil society organisations, for example, take on tasks such as evacuating civilians, providing training courses on international humanitarian law, investigating and, above all, documenting war crimes and crimes against humanity, repatriating prisoners of war and abductees, and rehabilitating veterans. Their great advantage is that they can often adapt more effectively to the rapidly changing dynamics of war than state agencies.

If the OSCE is still to be perceived as an authoritative institution in the field of conflict management in the future, it is likely that it will take on a complementary role in cooperation with other actors. For example, as an implementing organisation with a civilian mandate, it could be supported by international partner organisations with a robust mandate and vice versa. The OSCE Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine lacked such robust support to credibly punish violations of the ceasefire agreement.

Post-conflict rehabilitation

Should a ceasefire be achieved in Ukraine, the post-war or rehabilitation phase is likely to be the most promising time for the OSCE to be activated as an implementing partner. It has numerous tried and tested instruments, methods and extensive expertise in this area. Dealing with victims and prosecuting crimes are of central importance for achieving lasting peace. Civil society has an important role to play during this period, as it can build on its documentation of war crimes accumulated during the acute phase of the war / conflict.

Humanitarian demining, stockpile management of conventional ammunition and the control of small arms and light weapons are also important prerequisites for the normalisation of post-war societies. When landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO) are removed, contaminated land can be cultivated again and used for food production. Non-governmental organisations active in this sector combine technical and military expertise with social and humanitarian skills. They are therefore natural partners for the OSCE, which often acts as a bridge-builder in relations with local authorities and governments. However, as was lamented in background discussions, these organisations are not always recognised or perceived as such by the OSCE.

Structural challenges

As a primarily intergovernmental organisation, the role of civil society in the OSCE context is ambivalent: on the one hand, its involvement is officially desired, but on the other hand, the OSCE is a complex organisation, which complicates cooperation in practice due to a lack of focal points. This is compounded by the fact that the OSCE always decides by consensus, meaning that decisions can only be made if all participating States agree. This also applies to conflict resolution formats. Since these formats’ specific arrangements have usually been determined long ago by the parties to the conflict together with the OSCE and the respective mandate, they are relatively inflexible today. Renewing the consensus on this is currently impossible in many areas due to Russia’s obstructive behaviour.

Formal involvement

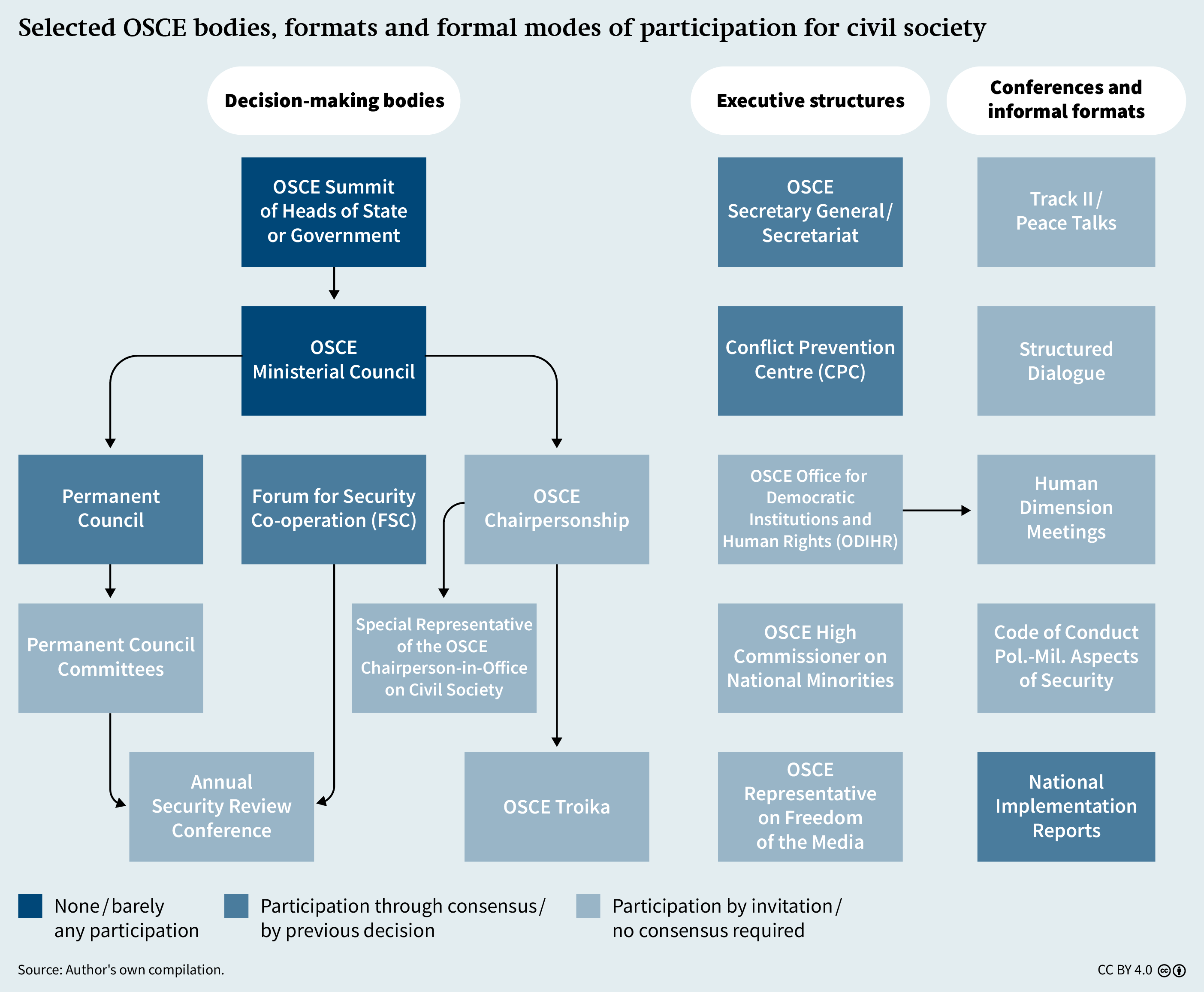

In principle, all OSCE bodies whose agenda is not decided by consensus but by the respective chairperson have the formal possibility of hearing representatives of civil society organisations (see graph on p. 5). However, systematic involvement does not take place in practice. The FSC meetings for example are characterised by a narrow agenda, as the participating States are usually only able to agree on a few common points. Nevertheless, civil society speakers have repeatedly been invited to the FSC security dialogues, on topics such as “women, peace and security”, “children and armed conflict” or “armed forces and the environment”. Ultimately, the participation of civil society representatives also depends on whether the first dimension involves so-called military (limited to the FSC) or non-military issues. The majority of interview partners did not see a deficit in civil society presence in the area of non-military issues.

Inclusivity

One of the core principles of the OSCE is inclusivity. In the field of mediation, this concerns, for example, the involvement of all parties to the conflict. In addition, the interviewed OSCE representatives considered inclusivity to mean more than just presence at the negotiating table, especially where certain processes are not supported by civil society. Ultimately, it is a question of striking a balance between inclusivity and exclusivity: a good process always takes into account who meets or is involved, when, where and how. Although inclusive processes are known to be more sustainable, civil society is not always (directly) involved because these processes initially start in an exclusive manner. In certain constellations, civil society can be involved at a later stage.

Under certain conditions, more inclusive mediation approaches are possible. One example of a relatively inclusive format is the Geneva International Discussions in the context of the Georgian conflict. The OSCE participates in these talks as co-chair. The process to resolve the conflict around Transdniestria (5+2 format, currently suspended) also provides for the involvement of experts from civil society organisations in the sectoral working groups. Although both formats have achieved improvements for the local populations in the past, they have made little political progress in recent years.

Informal cooperation

The precarious situation of the OSCE in recent years has led to a decline in interest in co-operation among civil society organisations. In fact, only a small circle of organisations works closely with the OSCE on a permanent basis. In addition, the OSCE is not a traditional donor organisation and the financing of projects must usually be provided by other sources or in the form of extra-budgetary projects funded by participating States. Co-operation with civil society is therefore often informal in nature. Critics complain that most of it takes place “off the record”, never finds its way into official OSCE documents and procedures, and thus does not enter the institutional memory of the organisation. They also argue that follow-up and feedback procedures are inadequate. Furthermore, the flow of information in the context of field operations has been criticised for often being one-sided: in the exchange and organisation of Track 2 or 3 dialogues (between civil society groups or societal groups, respectively), little is offered in return to the civil society that is consulted. National and international development co-operation projects offer good examples of how more systematic cooperation with civil society can look like.

Unnoticed rituals

Over time, interaction with the Civic Solidarity Platform network has taken on a more ceremonial character. For example, it has become an integral part of the annual civil society conference, which has been organised by the platform since 2010 in the run-up to the OSCE Ministerial Council, to adopt a declaration with recommendations to the OSCE institutions and participating States and submit it to the OSCE Chairperson-in-Office. In reality, however, these recommendations receive little attention: the majority of OSCE representatives interviewed were unaware of the platform or its conferences. Those who were aware expressed a wish for more realistically formulated recommendations. It seems likely that there is ultimately too little opportunity for dialogue here.

Conclusions

In the context of the eroding liberal consensus, which does not stop at the OSCE core states (Austria, Switzerland, Germany and the Nordic states), civil society representatives are finding themselves in an increasingly difficult position. The question also arises as to whether an incoherent, multi-layered actor such as civil society can still guarantee the implementation of the 1975 Helsinki principles today. Much within the OSCE depends on Russia’s current and future behaviour. In this unclear situation, the organisation is not only looking for a new role, but also for concrete ways to circumvent the consensus principle, for example in the form of extra-budgetary projects, which are mostly financed by like-minded states.

Similarly civil society could eventually cease to be viewed as a collective actor, but in a differentiated manner – with the consequence that certain tasks would be taken over by like-minded civil society organisations that are committed to the Helsinki principles and have the backing of governments that support extra-budgetary projects.

The German Federal Foreign Office should therefore refrain from cutting funding for the successful Eastern Partnership / Russia Programme (cooperation with civil society in the Eastern Partnership countries and Russia). On the contrary, the programme needs to be upgraded to strengthen the resilience of civil society in this region in the interests of crisis prevention, especially after the withdrawal of USAID.

Since security is a process that often works from the bottom up, and since the OSCE is a regional organisation, whose strengths lie primarily in networking and expertise at the local level, it is important that it remains active “on the ground” in the context of field operations. Given the damage to the OSCE’s reputation in Ukraine since 2022, it should make all the more effort to regain ground there. It should be more proactive than before in reaching out to Ukrainian civil society, for example by creating added value for the Ukrainian society through extra-budgetary projects. The establishment of citizens’ councils to advise on security policy, for example, could ensure that local structures become integrated into a mechanism that, after the end of hostilities, adapt any security regime to local conditions. It could thus take into account the people affected, their living conditions and their security needs. However, the chances of the OSCE participating in securing a ceasefire in Ukraine are currently considered slim.

Despite the expected reservations of the participating States, it would be advantageous for the OSCE to develop a reliable strategy to strengthen and structurally anchor civil society participation. Given the historically evolved role of civil society organisations and other non-state actors in the three dimensions, their systematic involvement in political-security deliberation processes is long overdue. In internal reform processes, the involvement of civil society should not be seen as an “add-on” but as an integral part of the organisation’s working processes. This requires reliable and sustainable participation formats as well as transparent communication channels, which could be established, for example, by the Special Representative on Civil Society.

An institutionalised but flexible framework, supplemented by a central contact point for non-governmental organisations within the OSCE Secretariat, could be a first step. This could be supplemented by a rotating consultation format among civil society organisations in the respective OSCE bodies, for example linked to the respective chairing country. This would help build trust, address legitimate criticism and position the OSCE as a credible actor in an increasingly fragile international order.

Dr Nadja Douglas is a researcher in the Eastern Europe and Eurasia Research Division. This article is based on findings from a project funded by the German Federal Foreign Office on the role of the OSCE in a new European security order, as well as a subproject on civil society engagement in the politico-military dimension of the OSCE, carried out in the first half of 2025. For the latter, 16 interviews were conducted with experts from civil society and academia, representatives of the participating States, and the OSCE Secretariat. In addition, a text corpus of around 2,600 OSCE documents was analysed using qualitative data analysis software and AI.

The author would like to cordially thank Celina Thadewaldt and Simon Muschick for their research support and assistance in designing the graph.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C35

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 36/2025)