Moscow Threatens the Balance in the High North

In Light of Russia’s War in Ukraine, Finland and Sweden Are Moving Closer to NATO

SWP Comment 2022/C 24, 31.03.2022, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2022C24

Research AreasRussia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is not based on legitimate or reasonable security interests – it is a blatant rejection of Europe’s security order. President Vladimir Putin already made this clear in his televised address on 21 February preceding the attack. Previously, Finland and Sweden had recalled the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) Final Act of 1975, to which Russia – as the successor state of the Soviet Union – has committed itself. According to the Helsinki Final Act, the sovereign equality of the signatory states is to be respected – and with it their right to choose their alliances freely. Moscow’s military aggression not only pushes Helsinki and Stockholm closer to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to an unprecedented extent, but it also makes the containment of Russian power an urgent matter once again. In the long term, it will have implications on the stability in the High North as well.

The Russian incursion has consequences beyond Ukraine. Repercussions in the Baltic Sea region and in the High North were already evident during the build-up of the war, and in the long term Russia’s aggression will also affect the Arctic. In addition to the Baltic States, Finland and Sweden – as Nordic member states of the European Union (EU) – are directly affected by the deteriorating security situation in Europe and around the Baltic Sea. Neither country is yet a member of NATO. In Helsinki, however, the “NATO option” is an integral part of security policy, and according to recent polls, the Russian war has prompted a majority of Finns (reaching up to 60 per cent) for the first time in Finnish history to support joining the alliance. The Swedish parliament already voted by a large majority in December 2020 in favour of the country’s future accession to the alliance, and recent polls from Sweden also confirm around 50 per cent support for NATO membership.

On 24 December 2021, the press department of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that President Putin’s demand to renounce the future enlargement of NATO also concerned Finland and Sweden. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov later withdrew the demand concerning the two Nordic countries and gave assurances that Moscow respected their sovereignty. In the same breath, however, he stressed that the military neutrality of Finland and Sweden was an essential part of the European security order. On 25 February 2022, the Kremlin’s press secretary, Mariya Zakharova, warned in a tweet that Finland joining NATO would have “serious military and political consequences”. The same threat was reiterated on 12 March in an interview with Second European Department Director Sergei Belyayev from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Tensions in the Baltic Sea Region

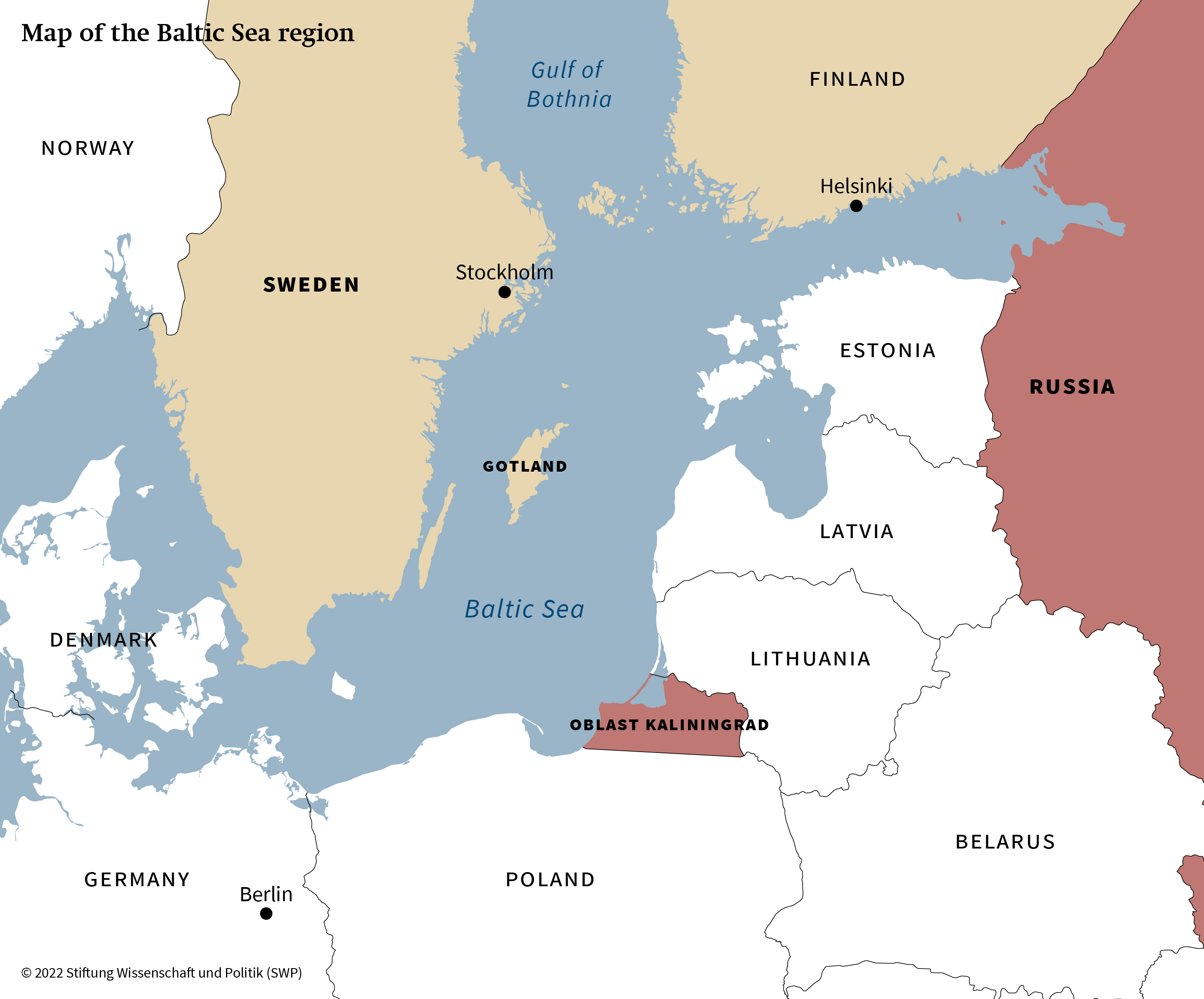

Military demonstrations of force have become “a firmly established instrument of Russian coercive diplomacy”. It therefore came as no surprise that Moscow’s demands for security guarantees – parallel to the troop build-up on the Ukrainian border – were accompanied by an increase in Russian activities in the Baltic Sea. In January, three Russian amphibious landing ships from the Northern Fleet arrived from Murmansk at the Baltic Fleet base in the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. As a reaction, Sweden increased its defensive readiness and had tanks demonstratively patrol the island of Gotland, which is located only 330 kilometres from Kaliningrad and considered a primary Russian target in the event of war. In mid-January, the warships of the Northern Fleet, together with three further warships, left the Baltic Fleet base for the Black Sea. At the same time, suspicious drone flights were spotted over three Swedish nuclear power plants. Furthermore, on 17 January 2022, a Russian cargo plane en route from Moscow to Leipzig made a detour over half of Finnish territory, thereby flying over two important Finnish military sites, including the air force headquarters and parts of the military intelligence service in Tikkakoski as well as the Halli military airport in Jämsä.

Such operations attract little attention in Germany because the Baltic Sea region is usually perceived as an economic area. In Northern Europe, on the other hand, the strategic importance of the region is the focus of security and defence policy. Finland’s new defence report from September 2021, for example, states that tensions in the international security environment have led to increased military activity in the Baltic Sea region.

Finland’s Geopolitical Room for Manoeuvre

With approximately 5.5 million inhabitants in an area almost as large as Germany, Finland is one of the most sparsely populated countries in Europe. It shares a 1,343 km long border with Russia and is dependent on foreign trade sea routes. Until the war in Ukraine, Finland’s geopolitical room for manoeuvre was strongly contingent on stable relations with Moscow as well as on broader European stability. Finland has therefore been a key participant in agreements on European security and cooperation. For example, in August 1975, the CSCE Final Act was signed in Helsinki.

Due to its geopolitical position in the immediate vicinity of Russia, Finland – unlike many Western European EU and NATO member states – never abolished compulsory military service and relies on a strong national defence. The country’s armed forces can reach a troop strength of 280,000 in the event of war and are equipped with modern weaponry. In December 2021, the Finnish government decided to purchase 64 F-35A Lightning II fighter aircraft from US manufacturer Lockheed Martin. The purchase guarantees a high degree of interoperability with NATO states and was therefore assessed in Russian media as an “unfriendly action towards Russia”.

In terms of foreign policy, Finland’s priorities were already marked by the deteriorating security situation in Europe according to a strategy paper of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for 2018–2022. Russia’s increased military presence in Finnish neighbouring areas since 2014 have required both a firm response and the continuation of regular dialogue. In the government’s new defence report of September 2021, the traditional focus on the Baltic Sea region shifts to a broader perspective that encompasses the Arctic and the northern Atlantic as one security political space.

The changing environment has thus led to stronger cooperation between the Nordic countries, especially Finland and Sweden, and in the transatlantic relationship. Sweden is Finland’s most important partner, providing the country with strategic depth in the event of conflict. Conversely, defence cooperation with Helsinki is very important for Stockholm, as Sweden does not have sufficient capabilities due to its military disarmament that began in the early 2000s. From Finland’s point of view, NATO’s presence and activities in the Baltic Sea region have a stabilising effect on regional security. Accordingly, Helsinki is seeking the closest possible cooperation with NATO, especially in air defence, which was the purpose of the multinational manoeuvre “Arctic Challenge” in June 2021. Finland and Sweden invited seven NATO countries, including Germany, to participate.

From the Finnish perspective, the EU, NATO, and Nordic cooperation are complementary elements, so that joining the alliance has not seemed necessary thus far. If Finland were to join, it should ideally be coordinated with Sweden. A Swedish application alone could dilute the NATO option for Helsinki because Finland would remain the only neutral state in Russia’s “buffer zone” or “sphere of influence”. The NATO option is an important and at the same time sensitive part of Finland’s security and defence policy – more so than ever in the current tense situation. That is why Finland reacted with alarm when Chancellor Olaf Scholz, at his press conference with Putin in Moscow on 15 February, said that NATO enlargement to the east would not take place during his term in office. Scholz did not explicitly specify that he was referring only to Ukraine. The statement was therefore interpreted to mean that Germany might block Finland’s accession to NATO as a concession to Russia. Although it was not his intention, Scholz’s statement touched a sensitive nerve in Finland.

Sweden’s Foreign Policy Tradition of Neutrality

Sweden follows a foreign policy tradition based on a deeply rooted neutrality as its political identity. Since 1814, Sweden has not been involved in a war. Non-alignment and peace efforts have traditionally been at the centre of Sweden’s foreign policy. At the same time, since the end of the Cold War, Stockholm has been pursuing a pragmatic security policy in which it is moving as close as possible to NATO, but without joining. A typical example of the Swedish approach is that the exact troop composition during an exercise of special units of the Swedish army with US troops in the autumn of 2020 in the country’s archipelago was kept secret.

According to Defence Minister Peter Hultqvist, Sweden must adapt to the changed situation, in which Russia is willing to use military means to achieve political goals, and an armed attack cannot be ruled out. In the period 2021–2025, the country’s defence expenditure is therefore to be increased by 40 per cent, and by as much as 85 per cent compared to the 2014 level. In the wake of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the Swedish government announced a further increase in defence spending, which is to reach 2 per cent of GDP from the current level of 1.26 per cent – without specifying a time frame, however. The number of personnel in the army is to be increased from 60,000 to 90,000 by 2025, and the navy is to receive two more ships and a submarine. There are also plans to equip the army and air force with new weapons systems and to improve the defence of Gotland, where a Russian invasion is expected in the event of a conflict. The island could become the “new Crimea”, from where Russia would control access to the southern Baltic Sea region. In addition, Stockholm wants to reactivate a civil defence system so that the country can hold out for three months in a war until help arrives. The naval base at Muskö has also been reactivated and exercise operations have resumed. The 2020 exercise, which was kept secret, likely took place with the support of US Special Operations Command Europe from Stuttgart. Even more remarkable is the Swedish decision on 27 February to supply weapons to Ukraine. The signal is clear: Even Sweden is backing away from its policy of neutrality because of Russia’s aggression.

“Freedom of Choice” under Pressure

In his 2022 New Year’s address, Finnish President Sauli Niinistö recalled Finland’s “freedom of choice” with regard to possible NATO membership. This reference was clearly addressed to Russia. According to Niinistö, there is no Finnish “model”, the so-called Finlandisation – in a sense voluntarily limiting its sovereignty – neither with regard to Ukraine.

In Finland, Russia’s war against Ukraine has brought about a historic shift in support for Finnish NATO membership. In a poll conducted on 28 February, a majority of Finns were, for the first time, in favour of joining the alliance: 53 per cent were in favour, only 28 per cent were against, and 19 per cent were unsure. The numbers in favour have since increased further and stabilised at around 60 per cent supporting Finland joining NATO.

The change of mood has also affected the political parties. Of the five governing parties, the Finnish Centre Party and the Left Alliance were previously against joining, while the Swedish People’s Party (the party of the Swedish-speaking minority) wanted membership by 2025. The Greens were internally divided, with the Greens parliamentary group’s leader, Atte Harjanne, advocating membership even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Social Democratic Party has traditionally taken a similar line to President Niinistö. Accordingly, the NATO option remained an important pillar of Finnish security policy, and no need was seen for the time being to abandon the non‑alignment policy.

However, the war in Ukraine has fundamentally changed the security policy calculations in Finland. Since the Russian invasion, more and more politicians in all parties have expressed a change of heart and come out in favour of Finland’s immediate accession to NATO. A national citizens’ initiative for a landmark referendum on the issue collected the necessary 50,000 votes within five days to trigger a parliamentary process.

In Sweden, a parallel development is under way. In the parliament, a majority emerged for the first time in December 2020 to prepare a NATO accession option. A year later, Russia’s demand that it reject any NATO expansion near its border also created alarm in Sweden. “In Sweden, we decide for ourselves with whom we cooperate,” declared Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson, in office since November 2021, and announced a “deepening of the partnership between Sweden and NATO”. In a recent poll after the start of the war on 4 March 2022, also for the first time in Swedish history, 51 per cent of respondents were in favour of joining NATO. Further opinion polls have since recorded somewhat varying degrees of support between 40 and 50 per cent. Moscow’s tough demand for more consideration for its own security interests and its attack on Ukraine have thus achieved the exact opposite of what was intended with its neighbours in Helsinki and Stockholm: Russia’s pressure has had the paradoxical effect of bringing Finland and Sweden closer to NATO.

Before Russia’s attack – and again after a month-long continuation of the war – some Western heads of state and government seemed inclined to consider a neutral status for Ukraine outside of NATO as a negotiation option. In this scenario, as a possible concession to Russia, Ukraine would not be able to join NATO for a certain period of time. From Finland’s point of view – whose historical experience with the Soviet Union gave rise to the term “Finlandisation” – this option should be viewed very critically. Since Ukraine, due to its lack of territorial integrity, had no realistic chance of joining NATO until the start of the war in any case, the idea of a moratorium was counterproductive. Excluding Ukraine from the prospect of NATO membership, even if only temporarily, could also mean excluding Finland. Although the two cases are not entirely comparable – not least because of Finland’s EU membership – it is conceivable in a worst-case scenario that Russia could make similar demands and use similar means of escalation against Helsinki in the future. Would the member states of the alliance then be prepared to close the “NATO door” to Finland as well? After all, an agreement on a new security architecture for Europe – as a self-imposed precondition for admitting further NATO members – could still be many years away.

Implications for the Security of the Baltic Sea Region

Finland is an attractive defence partner for NATO in the High North due to the reserve strength of its armed forces and their modern equipment. Since 2014, the strategic importance of the Baltic Sea region has increased, which at the same time has enhanced Finland’s role. In the event of an attack by Russia, Finland would have an important role to play in the defence of the Baltic Sea region. Thus, in Estonia, the Finnish decision to acquire F-35 fighter aircraft was seen as being very beneficial for the defence capacity of the entire region.

NATO member Norway’s intensified defence cooperation with Finland and Sweden also contributes to strengthening regional security in the entire Baltic–Arctic–North Atlantic region. Although Sweden lags far behind Finland in terms of the capacity of its armed forces, the close security and defence cooperation between the two countries is complementary for both sides. If they were to join NATO, this would enable almost immediate operational readiness within the alliance. Thus, the accession of the two Nordic states would be quite beneficial for the collective security of NATO’s northern flank.

De facto, Finland and Sweden have already adapted their defence policies to NATO to such an extent that the status of the two countries no longer corresponds to neutrality in the strict sense of the term. Under normal circumstances, their accession to the alliance would therefore be almost a mere matter of formalisation. How Russia would react to it, however, is difficult to foresee in the current escalating situation. Putin has often emphasised that Russia would not readily accept Sweden’s or Finland’s membership in the Western alliance. In 2017, for example, he described Sweden’s accession to NATO as a threat to Russia and announced already in 2016 that he would deploy Russian troops to the common border in response to Finland’s accession. Similar threats have been frequently reiterated by Putin himself and other Russian authorities. Given Russia’s decision to wage a war of aggression against Ukraine, there is no certainty that Putin would not indeed pursue this course.

Long-term Consequences for the High North and the Arctic

Russian warfare has ushered in a new era in the European security order. Countries such as Finland, Sweden, and Germany, which have traditionally been reluctant to export arms to conflict areas, decided within a week to supply weapons to Ukraine. For the first time in its history, the EU has taken a joint decision to supply an attacked country with weapons and has supported Ukraine militarily with equipment and supplies worth €1 billion, funded from the European Peace Facility. Even neutral Switzerland has joined in the far-reaching EU sanctions against Russia.

The long-term effects of these monumental changes cannot yet be foreseen in their entirety, but it is already clear that Moscow’s war has had an explosive impact on the balance in the High North. In Europe’s northernmost region, Western partners have so far sought balance and cooperation with Russia, while Russia itself has also been cooperative in view of its security and economic interests. In 1989, Finland initiated the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS) in Rovaniemi, and the Rovaniemi Declaration was signed in 1991, which led to the founding of the Arctic Council. At that time, environmental protection and the peaceful use of natural resources in the Arctic offered a common denominator to get all Arctic states to the negotiating table.

As a NATO member state, Norway has always maintained a balance between deterrence through membership in the alliance and reassurance towards Russia. On the one hand it has held exercises with NATO allies, but on the other hand Oslo has not allowed a permanent presence of NATO units in its territory. Such acts of self-constraint lose their meaning, however, when Russia becomes increasingly aggressive and militarily attacks the sovereignty of its neighbouring states. In doing so, Moscow is abandoning the principles of international law and the CSCE Final Act – which include refraining from the threat or use of force directed against the territorial integrity or political independence of another state. As a result, Norway has already significantly expanded its cooperation with the United States.

The changed security situation of the Arctic region is reflected in the recent strategy documents of Finland and Sweden. For example, the Finnish military intelligence service made public a review for the first time in 2021 in which it soberly notes, with regard to Russia, that Arctic states were also seeking to assert their interests through military means. In addition, the country’s latest defence report states that the significance of the great power rivalry has increased in the High North. Arctic sea routes are becoming more accessible due to climate change, which is progressing much faster closer to the poles, thus creating new opportunities to exploit resources. The Arctic is particularly vulnerable to spill-over effects from other world regions due to the growing great power rivalry and Russia’s military capacities placed there. The fact that Moscow is increasing its military capacities in the Arctic creates a high potential for escalation. Finland’s new Arctic Strategy of June 2021 also emphasises how strongly the Arctic security situation is interwoven with (negative) developments in other regions. Security policy developments in the Arctic thus influence Finland’s overall national security and are closely linked to the Baltic Sea region and the rest of Europe.

In Sweden’s new Arctic Strategy of October 2020, security policy is also given a higher priority. The previous strategy from 2011 stated that the security challenges in the region were not of a military nature. The new strategy paper, in contrast, not only emphasises the need for peace and stability, but also notes a “new military dynamic in the Arctic”. Foreign Minister Ann Linde emphasised the growing strategic and economic importance of the Arctic. Sweden must adapt to the changes taking place there. The strategy document states that the Arctic has long been considered an area of low tension, with favourable conditions for international cooperation. However, climate change and the changing geopolitical situation bring new challenges.

(Re-)Containment of Russian Power

In terms of security policy, all Nordic states have their ties with NATO in common – albeit to different degrees. In addition, Northern European defence ministers agreed in Oslo in November 2018 to step up the Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO) and to improve interoperability.

The security interests of the Nordic states have tended to converge over the past decade, largely because of Russia. Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Nordic governments have increasingly found a common denominator in this area – despite their different Euro-Atlantic frameworks, which have made security policy cooperation difficult to a certain extent in the past. Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, for example, are members of the EU, while Norway and Denmark are NATO members. Denmark, however, does not participate in the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) due to its opt-outs in the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy – although this decision could be reversed in a referendum scheduled for 1 June 2022. Whereas Norway, despite being formally outside of the EU, has an opt-in to participate in the same policy area. Finland and Sweden already have a high level of interoperability with NATO structures, although neither country is yet a member of the alliance.

In September 2020, the defence ministers of Finland, Norway, and Sweden signed a memorandum of understanding in response to the heightened military activities on the Russian side, which were already recorded at that time. According to the memorandum, the three countries want to conduct joint operations in future crisis and conflict situations (with Norway planning to transfer command to NATO in the event of a crisis and war), establish a strategic planning group for this purpose, and coordinate national operational plans. The decision by Denmark, Finland, and Norway to acquire F-35 fighter aircraft contributes towards interoperability with US forces.

Beyond regional cooperation, the United Kingdom remains the most important European partner in security and defence policy for the Nordic states, despite Brexit. Although Germany is considered a like-minded partner in many areas, it is not yet perceived as a key security policy actor in the Nordic states. However, this could change after Chancellor Scholz’s announcement of €100 billion in special funds for the Bundeswehr. For Germany, as a country bordering the Baltic Sea, it is necessary to take greater strategic (and defence policy) account of the North and to understand the Arctic–North Atlantic region – in a similar way as Finland, but also Russia – as one coherent sphere in terms of security policy. Defence cooperation in the North is currently developing very dynamically, and a closer connection with Germany would be advantageous due to its geographical location on the Baltic Sea. The Bundeswehr has already taken the first steps in this direction. In mid-February 2022, for example, the German navy conducted joint exercises with the Finnish and Estonian navies to show solidarity on NATO’s northern flank.

Moscow’s war course is giving new impetus to defence cooperation in the North and will probably lead to an expansion of NORDEFCO and an intensification of cooperation with the United States. The Kremlin’s long-standing assertion that the West would eventually attempt to constrain Russia’s power has now become a self-fulfilling prophesy as a result of the war in Ukraine. Whether the threat to Russian security claimed by Putin corresponds to reality is irrelevant, insofar as he has been acting according to this narrative since 2007, thus creating real consequences for all of Europe. This presents the West with a dilemma: It is not possible to meet excessive Russian security demands without compromising its own core values, principles, and interests.

Russia has a strong self-interest in the stability of the Arctic–North Atlantic region because its security and economic models depend on it. Thus, Moscow’s aggression is counterproductive, not only because it brings the West closer together and strengthens the will in Ukraine to defend its sovereignty. It is also counterproductive in terms of peace and stability in the High North, a region on which Russia remains dependent economically. However, economic considerations no longer seem to play a prioritised role in Moscow’s calculations; in case of doubt, national security – or regime security – takes precedence over economic interests. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that a similar escalation could follow in the High North as long as Putin’s regime stays in the Kremlin.

Minna Ålander is Research Assistant in the EU / Europe Research Division at SWP.

Dr Michael Paul is Senior Fellow in the International Security Research Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2022

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

doi: 10.18449/2022C24

(Revised and updated English version of SWP‑Aktuell 19/2022)