The Limits of Multilateral Climate Policy

COP30 and the Conflict Between Petrostates and Electrostates

SWP Comment 2026/C 05, 03.02.2026, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2026C05

Research AreasThe fossil-fuel foreign policy of the United States under President Donald Trump has intensified the conflict between petrostates and electrostates in international climate politics. At COP30 in Belém in November 2025, this cleavage was particularly evident in the dispute over a roadmap for the Transition Away from Fossil Fuels (TAFF). While an increasing number of countries regard TAFF as a necessary consequence of the global energy transition, fossil fuel producers prevented any substantive progress being made. The conference highlighted the structural limits of the capacity of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to mediate this distributional conflict. As a result, the EU faces a strategic dilemma: to further politicise the COP process around TAFF or to prioritise the stabilisation of key mechanisms of the Paris Agreement. Whether it can overcome that dilemma will become apparent during the run-up to the next global stocktake, which is due at COP33 in India in 2028.

Ten years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, the formation of two blocs – petrostates and electrostates – has become a structuring factor in geopolitics and international climate policy. Profound political and economic shifts underlie this division: several large economies are accelerating the transition to electrified systems and basing both their energy security and their international influence on clean tech. China is the prime example, with its prominent position in green supply chains and rapid expansion of renewable energies. Other states – including, most recently, the US – are pursuing a fossil-fuel foreign policy that secures their existing rent structures and ensures their ability to expand or preserve dependencies around the globe.

This bloc formation between electrostates and petrostates shaped the political dynamics of the 30th UN Climate Change Conference. In fact, its influence had already been evident during the run-up to COP30, when the US, together with Saudi Arabia, prevented an agreement on the decarbonisation of international shipping being reached. Although Washington did not send an official delegation, the Trump administration exerted pressure behind the scenes both before and during the conference, targeting small Caribbean island states, in particular. By withdrawing from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Trump administration wants to ensure that the US will not be able to participate in climate negotiations in the long run. In Belém, other petrostates, having traditionally rejected ambitious decisions, felt vindicated in their stance. That applied, not least, to Russia, which once again vociferously defended its positions after having remained on the sidelines for several years.

Against this background, the debate on the Transition Away from Fossil Fuels (TAFF) became the central political focal point of the bloc formation at COP30. While a growing number of countries see TAFF as a necessary consequence of the global energy transition, fossil fuel producers view it as a threat to their economic and geopolitical standing. COP30 made clear that the structural framework of the UNFCCC is far from being able to address this conflict in a productive way and translate it into robust decisions. The consensus principle and the ongoing formal separation between industrialised and developing countries are allowing a small group of states to prevent progress even when broad majorities do fundamentally exist. Thus, the question of whether and how TAFF can be negotiated in the multilateral climate regime is becoming a litmus test for the functioning of the UNFCCC as a whole.

The results of COP30

The official COP30 agenda included a number of technical negotiating points on which at least some, albeit limited, progress was made. Among the results achieved were the agreements reached on the indicators for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), on the establishment of a Mechanism for a Just Transition and on the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF – see SWP Comment 1/2026). This demonstrates that, even under difficult geopolitical conditions, the multilateral climate process remains capable of action.

Inadequate Nationally Determined Contributions

In the run-up to COP30, the parties to the Paris Agreement were asked for a third time to submit new or updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Although the NDCs themselves were not included on the official agenda, the conference marked an important moment in the five-year ambition cycle of the Agreement (SWP Comment 33/2024).

Overall, the NDCs for 2030 and 2035 submitted before the conference were barely more ambitious than the previous generation of contributions. Together with the renewed withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, the latest commitments would keep the world on a warming path of around 2.6 degrees Celsius until the end of the century. Moreover, only about two-thirds of the signatory states submitted new or updated NDCs; major emitters such as India and Saudi Arabia failed to submit any contributions before the conference; and China’s reduction target was low – just 7–10 per cent by 2035.

The EU linked its own NDC to the internal process for setting the 2040 climate target (SWP Comment 14/2024), and its members were able to agree on a common position only just before COP30. In the run-up to the conference, there was virtually no coordinated ambition diplomacy, unlike ahead of COP26 in Glasgow and the second round of NDCs. Targeted attempts to put pressure on hesitant states through political signalling or joint announcements were all but lacking. COP30 confirmed that the ambition mechanism of the Paris Agreement has little leverage without active political support – and that despite the UN having recently acknowledged for the first time that the target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is likely to be breached.

The Mutirão decision

Nevertheless, the Brazilian COP Presidency managed to make full use of its room for manoeuvre and address issues not included on the formal agenda. The starting point was what has become the almost routine dispute over the adoption of the agenda at the beginning of the conference. The group of like-minded developing countries (LMDCs) once again proposed that the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) be included on the COP agenda for discussion in order to problematise it as a “unilateral trade measure” that is detrimental to international climate cooperation. They also requested a separate agenda item on Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which regulates the financing obligations of industrialised countries, to tackle what they consider to be the insufficient climate finance targets that were set in 2024.

A novelty was that the EU, too, introduced its own agenda item, which addressed transparency and reporting (Article 13), while the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) called for a review of the status of NDCs. Thus, the so-called progressive coalition sought to promote two issues – ambition and transparency – that were directly pitted against the two advanced by the LMDCs – trade and financing.

For its part, the Brazilian Presidency made the conscious decision to depart from the usual procedure of informally sounding out delegations about the proposals and postponing any discussion about them in the absence of consensus. Instead, all four issues were discussed together in a consultation lasting several days. Ultimately, this new approach resulted in the so-called Mutirão decision, which, though not a classic cover decision, led to the controversial issues being put on the agenda. In this way, the technical nature of the remaining agenda items could be offset and the relevance of the conference ensured.

In the end, the Mutirão decision proved to be the most important outcome of COP30. It provides for a number of new dialogue and work formats, even if the mandates are characterised by vague wording and a high degree of ambiguity. A new work programme is to facilitate discussions over a two-year period that will seek to increase climate financing, with a focus on public funds. At the same time, the volume of funding for adaptation measures – a key demand of many developing countries – is to be tripled by 2035.

In addition, three annual dialogue formats have been established to discuss trade measures and climate cooperation. For the EU, this will mean defending the CBAM as a climate policy instrument. The “Global Implementation Accelerator”, a voluntary format led by the Brazilian Presidency, aims to link NDCs to support measures. In addition, the “Belém Mission to 1.5” will monitor and report on overall progress towards implementing the NDCs. The mission is to be headed by the presidencies of COP30–32.

Also noteworthy is a COP decision that implicitly acknowledges for the first time that global warming is likely to overshoot the 1.5 degrees Celsius target by the early 2030s (SWP Comment 47/2025). Finally, the majority of countries – against resistance from the LMDCs – defended the role of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as the provider of the “best available science”.

Roadmap for transitioning away from fossil fuels

However, though not part of the consultations on the Mutirão decision, the most contentious issue of the conference was a possible roadmap for TAFF – one that would build on and further operationalise the energy package that resulted from the first global stocktake at COP28 in Dubai in 2023. At that conference, “transitioning away from fossil fuels” was explicitly mentioned for the first time in a COP resolution. Since then, Saudi Arabia, in particular, has systematically fought against any further reference to the term “transitioning away”, while the EU and its allies want it to be established as a guiding principle for the energy transition.

The EU had not included a TAFF roadmap among its priorities for COP30. Even within the Brazilian government, there were differing assessments as to whether such a roadmap could be realised. While the Foreign Ministry, which is the responsible agency for Brazil’s COP Presidency, treated the issue with caution, Environment Minister Marina Silva publicly pushed for a stronger TAFF anchoring. Surprisingly, President Lula took up that position in his opening speech and thereby endowed the debate with political momentum. In the second week of negotiations, a small group of countries led by Colombia and the EU attempted to push forward a TAFF roadmap. Although the discussions gained traction in informal formats and in the media coverage, they were not part of the formal negotiations for most of the conference.

EU on the defensive

COP30 marks the EU’s strongest attempt to date to make TAFF the main political theme of the COP process. Until then, the had focused its efforts on expanding renewable energies – for example, through the inclusion of sub-targets on batteries and grids in the energy package. However, the dynamics in Belém showed how high the hurdles are for a decision on TAFF to be reached as part of the UNFCCC process and how limited Europe’s influence is under the current geopolitical conditions.

Instead of acting from a position of relative strength, the EU entered the negotiations from a position of structural weakness. As a result of the late submission of its own NDC, internal disagreements over its scope and design, growing domestic opposition to climate protection measures and the funding cuts for international support measures, Europe’s room for manoeuvre was limited ahead of the conference. While Italy and Poland allowed themselves to be persuaded and brought on board, enabling the EU to present a united front in support of a TAFF roadmap, an agreement was not reached until the end of the second week of negotiations, which was too late. Moreover, the EU delegation included a large number of new staff who were not yet used to working with one another. Even though the EU was able to more clearly define its role during the course of the conference, it could not avoid leaving the impression that the shift to promoting TAFF had been undertaken at relatively short notice and without sufficient preparation.

Progressive coalition under pressure

Against this backdrop, the EU found it increasingly difficult to form a broad progressive alliance. Ongoing criticism of the CBAM, particularly from India and other LMDCs, put a strain on diplomatic resources and shaped the political environment. At the same time, it was evident in almost all strands of the negotiations – and particularly in the Mutirão discussions – that many developing countries were not happy with the climate finance target agreed at COP29.

Delegations from small island states and other particularly vulnerable countries – which, traditionally, are allies of the EU – expressed concern that the Union would use adaptation and financing issues as bargaining chips to achieve the strongest possible TAFF wording. The renewed withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement further exacerbated the tensions: the EU became the focus of criticism from developing countries and was no longer able to position itself behind the restrictive line that Washington had usually drawn on financing issues in the past. In addition, the EU was confronted with expectations that could be met only to a limited extent owing to the limited fiscal leeway.

The fossil fuel bloc

A key reason for the failure to reach agreement on a TAFF roadmap lay in the structural and political power framework of the UNFCCC. The fossil fuel bloc – which was led by the Arab group around Saudi Arabia and supported by Russia and various fossil fuel-exporting countries from Africa and Latin America, among others – repeatedly used the consensus principle to prevent any wording that would have further consolidated or concretised the compromise reached in Dubai.

The EU was unable to achieve the diplomatic isolation of the core states of this bloc. In the recent past, it had succeeded in doing so thanks to a division of labour with the US: the EU had formulated ambitious demands and the US had overseen the political confrontation with the Arab fossil fuel producers. In Belém, things were different: the increasingly confrontational foreign policy of the US and the pressure tactics used by Washington in other climate policy contexts – including tariff threats and visa restrictions – reduced the willingness of some developing countries to openly oppose the petro bloc.

Even China, with its economic and geopolitical interests as an electrostate and its status as a leading exporter of renewable energy technologies, in effect sided with the LMDCs and the Arab group. Beijing deliberately acted with restraint in Belém and avoided exposing its role as a driving force. Instead, it once again emphasised its self-identification as a developing country and prioritised political cohesion with the major emerging economies of the Global South. For its part, the EU failed to translate the contradiction between China’s clean tech-based power projection and its defensive positioning within the UNFCCC into political pressure that might have prompted China to assume responsibilities aligned with its long-term geo-economic interests.

No agreement on fossil fuels

The outcome of COP30 regarding fossil fuels was ambiguous. On the one hand, a formal agreement on TAFF within the UNFCCC was not reached and the issue was addressed in the final text only indirectly through a reference to the results of COP28. (Even the G20 summit that was held at the same time came up with stronger language.) On the other hand, the Brazilian Presidency announced that it would initiate a voluntary process. This process envisages a series of high-level dialogues between the governments of producer and consumer countries, with reports being delivered to future COPs. Colombia and the Netherlands want to supplement the process with an international conference – already planned for April 2026 – on phasing out fossil fuels. In addition, President Lula announced post-Belém that a national Brazilian roadmap would be drawn up.

This ambiguous outcome can be attributed not least to the suboptimal strategic planning and negotiation skills of the TAFF proponents. On the Brazilian side, the presidential team repeatedly played down the chances of an agreement, despite Lula’s demands. The Presidency repeatedly called attention to the supposedly equal number of proponents and opponents (“80 vs 80”). However, on closer inspection it was revealed that the opponents by no means included all the African countries and that the proponents had a larger base. In the final phase of the negotiations, the Presidency presented a rather unambitious text as a basis for discussion that was strongly oriented towards the demands of the LMDC group, whose membership is more or less the same as that of the BRICS group, currently chaired by Brazil.

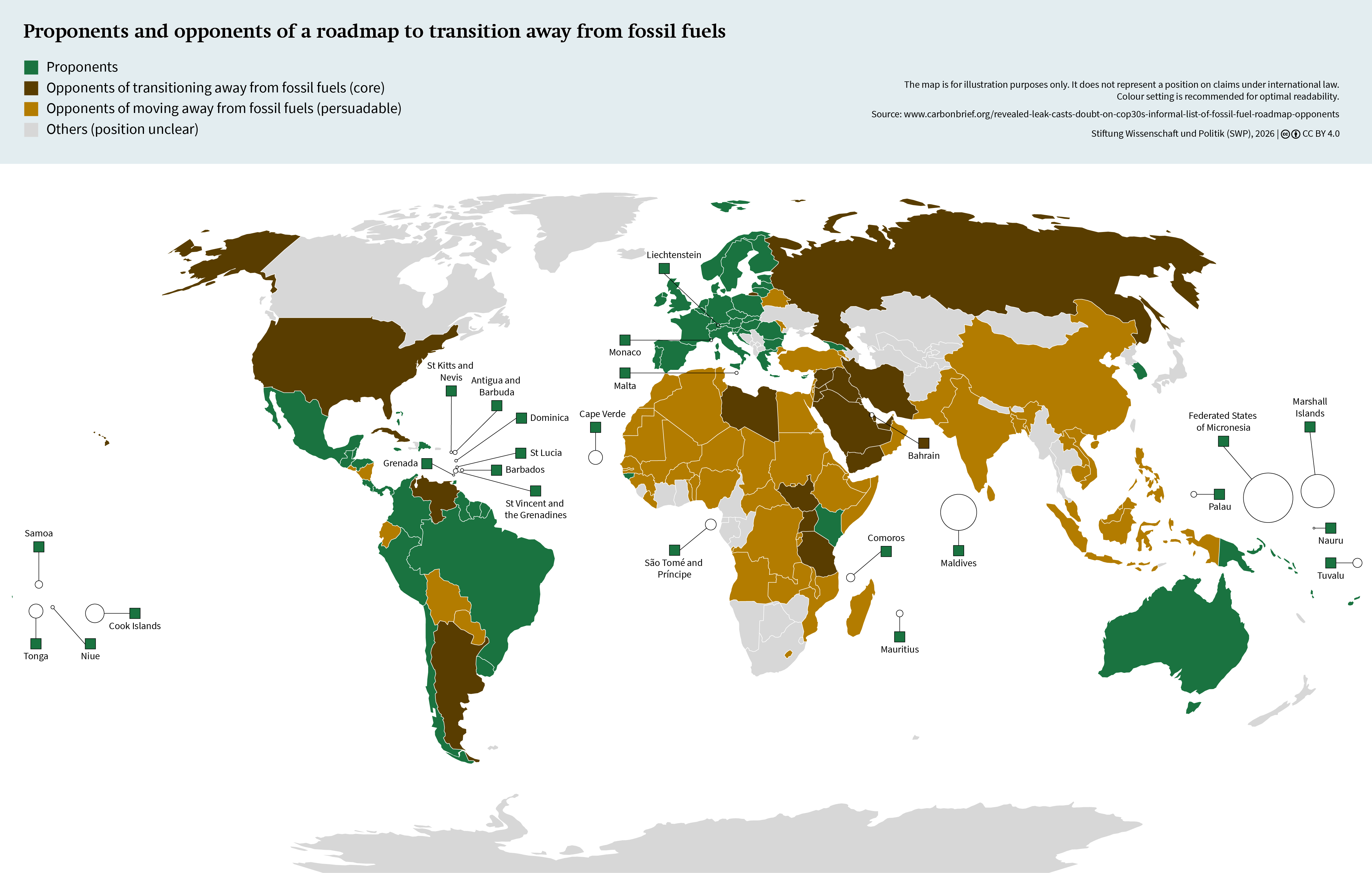

As the map on p. 6 shows, Colombia and the EU failed to mobilise a clear majority for a TAFF roadmap. The pro-TAFF coalition was significantly smaller than earlier such progressive alliances, which had brought together more than 120 countries: While it accounts for a majority of global gross domestic product (around 53 per cent), it represents only 36 per cent of the world’s population. Moreover, the opponents (including the US) account for more than half of global fossil fuel production and the proponents for just 21 per cent (24 per cent of countries cannot be clearly classified).

At the same time, there are countries outside the core fossil fuel group that do not necessarily draw a red line on this (see the ochre-shaded countries on the map). They may be willing not to actively oppose a TAFF roadmap. Indeed, some African developing countries have already signalled they could be open to persuasion, as have India and China.

However, the consensus principle that applies within the UNFCCC remains a major hurdle. Under the current circumstances, the EU was neither willing nor in a position to allow the negotiations to ultimately fail as a result of resistance from fossil fuel producers. While some allies discussed that option, it was evident that the EU put more emphasis on preserving the ability to act multilaterally and presenting a united front among UNFCCC members. This raises the question of whether it was wise from a strategic point of view to turn the UNFCCC into an arena for confrontation between petrostates and electrostates by focusing on a TAFF roadmap. While the TAFF debate reflects real shifts in the global energy economy, it also exacerbates institutional tensions in a process geared towards consensus-building.

Structural limitations of the UNFCCC

Here, the fundamental question arises as to whether and in what form the transition away from fossil fuels will or should remain the main bone of contention at the UNFCCC negotiations in the coming years, not least during the run-up to the second global stocktake, which is due at COP33 in India in 2028. What happened in Belém demonstrates that there are two dimensions to this question. On the one hand, TAFF addresses the core political-economic challenge of the global energy transformation. Addressing that challenge could help move the UNFCCC process away from an approach oriented solely towards target-setting. If the focus is to be placed on implementation, the issues of fossil fuel production and dependency structures will have to be addressed, as will the geopolitical consequences of the energy transition.

On the other hand, no substantive agreement was reached at COP30 because of the structural limitations of the multilateral climate regime. Belém has made clear that the institutional framework of the UNFCCC is of limited suitability when it comes to moderating fundamental distributional conflicts over the energy transition. Because of the consensus principle and the persistent division into industrialised and developing countries, the prevailing balance of power in the negotiations is unlikely to change in the medium term. Although debates continue about the need to overhaul the UNFCCC, there is little chance of reforms being passed under the current political conditions. The idea that the gradual intensification of the TAFF debate within the existing framework would automatically lead to significant progress is not supported by the results of Belém.

Consequently, there is a risk that the political push for the TAFF roadmap – both during the negotiations and in the public follow-up – will now stagnate at the symbolic-political level and the other main elements of the Paris Agreement will recede further into the background. NDCs would be affected, in particular. Indeed, the third NDC round showed that just when the United Nations was acknowledging for the first time that the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit is likely to be breached, the Paris Agreement was unable to prove its effectiveness. The EU’s decision to give political priority to TAFF under such conditions must be understood as a strategic prioritisation – one that, at best, might send a political signal on the issue of fossil fuels.

Strategic dilemma for the EU

This leaves the EU faced with a strategic dilemma. If TAFF is to be the core issue within the UNFCCC, Europe must be credibly prepared to intensify the political confrontation with fossil fuel producers. Logically, as the drama of the final phase of the negotiations in Belém indicated, this would require the EU to accept the failure of future COPs and explicitly put the blame on the blocking role of individual petrostates. For such a strategy to have any chance of success, the following would be required: a stable internal position on climate and energy policy, adequate fulfilment of the commitments to provide financial assistance to developing countries and long-term diplomatic efforts to build a coalition for phasing out fossil fuels. If the EU is unable to meet those conditions, any failure threatens to be perceived not as an ambiguous political signal but as European weakness.

Such a strategy could also form the basis for encouraging China to take on more responsibility. The People’s Republic has a serious interest in ensuring the continued functioning of the multilateral climate regime, but at present it is unwilling to act in keeping with its economic role as a provider of clean tech.

For the time being, advancing the TAFF roadmap outside the UNFCCC makes more sense. So far, short-term actionism has been the defining feature of the issue at the international level. For example, it is not yet clear what elements a TAFF roadmap might contain and how it should relate to national phase-out plans. The international conference on phasing out fossil fuels scheduled to take place in Colombia in April 2026 offers an opportunity to organise a coalition for transitioning away from fossil fuels and anchoring the issue in the international climate agenda. It could also be used to determine the conditions under which countries that are not part of the core group of fossil fuel proponents would participate in processes and political declarations and what support their participation would require. It is important that the process extends beyond the Colombian conference and the Brazilian Presidency’s initiative and is shielded from disruptive forces, such as those originating in the US. At the same time, existing links to the UNFCCC process should be kept open so that it is not undermined by parallel structures.

By the time of COP33, the EU should have defined its priorities more clearly. Does it want to continue to escalate TAFF as the main contentious issue within the UNFCCC, with all the risks that entails for multilateralism and alliance-building? Or does it want to more sharply focus its limited political resources on stabilising the core mechanisms of the Paris Agreement and promote TAFF in other formats? Both paths will require that preparations begin much earlier, are carried out more consistently and prove politically more robust than was the case in the run-up to COP30 – especially with regard to China.

Jule Könneke is an Associate in the Global Issues Research Division and head of the project “German Climate Diplomacy in the Context of the European Green Deal”. Ole Adolphsen is an Associate in SWP’s Global Issues Research Division and on the project “Climate Foreign Policy and Multi-Level Governance”. Both authors are members of the Research Cluster Climate Policy and Politics.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2026C05

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 1/2026)