Strategic Raw Material Cooperation between Africa and Europe

Making EU External Instruments Fit for African Industrial Drive and European Resilience

SWP Comment 2026/C 07, 09.02.2026, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2026C07

Research AreasAfrican governments are entering the geopolitical competition over critical raw materials with a growing sense of strategic confidence. While the AU-EU Summit in Luanda in November 2025 reaffirmed political commitments on both sides, European initiatives continue to lose ground. It is true that the Critical Raw Materials Act has expanded the EU’s diplomatic footprint; however, its limited project pipeline and fragmented financing under the Global Gateway have left the bloc unable to match the speed and scale of competing offers notably from China, the Gulf States and the US. African partners expect cooperation on industrial projects and deeper integration into value chains. With stronger internal coordination and increased financing under the next Multiannual Financial Framework, the EU can strengthen both its ability to deliver and its credibility.

African governments are increasingly repositioning themselves amid the growing global demand for minerals and the intensifying geopolitical competition. As current or future producers of copper, cobalt, graphite and other minerals, they are adopting a more assertive approach, more closely aligning their raw material policies with domestic industrial objectives and recalibrating their engagement with international partners accordingly.

At the continental level, the African Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS), which the African Union (AU) adopted in 2025, seeks to promote local value creation and regional supply-chain integration. Governments from Johannesburg to Dar es Salaam are courting investment not only in mining but also in mineral processing and enabling infrastructure.

This repositioning is shaped by a broader geoeconomic turn. Global competition over resilient supply chains has evolved into a contest over industrial sovereignty, at the centre of which stand critical raw materials (CRMs). For its part, the European Union (EU) is still searching for a coherent response to this development. Decoupling from non-European supply is neither realistic nor desirable, as Europe’s demand cannot be met domestically. Thus, the bloc’s increased resilience in mineral supply chains depends on diversification based on reliable external partnerships.

At the AU-EU Summit in Luanda in November 2025, the two sides reaffirmed their commitment to multilateralism and CRM cooperation. With CRMs now increasingly addressed through industrial and geopolitical lenses, the EU must use the 2024 Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) to adjust its external instruments – including the EU budget and the engagement of the European Investment Bank (EIB) – in order to engage effectively with external actors on this issue. The twofold goal should be to promote its own diversification goals and respond to Africa’s increasingly assertive industrial strategies.

African states’ industrial ambitions and strategic agency

Many African states remain heavily dependent on the export of unprocessed raw materials, a model that captures a limited share of value and reinforces the weak upstream and downstream linkages to the wider economy. In 2024, more than half of African countries derived at least 60 per cent of their export revenues from oil, gas or mineral commodities. Rising global demand and geopolitical competition over CRMs have strengthened Africa’s strategic agency, prompting renewed efforts by the AU and mineral-rich states to use resource endowments as levers for industrial development and thereby increase local value addition. Though long articulated – most notably in the Africa Mining Vision (AMV) of 2009 – this ambition has become a political focus once again.

Against the backdrop of the global green energy transition and the associated growing demand for minerals, the AU’s African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC), together with the African Development Bank (AfDB), began work on the AGMS in 2022; the strategy was formally adopted in March 2025. Building on the AMV, it aims to strengthen continental coordination and strategic positioning amid intensified global competition by promoting regional initiatives, such as shared infrastructure and the development of green industrial value chains. Implementation is to be supported by a Green Minerals Development Fund and public–private investment platforms, among other instruments. Mineral stewardship and environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards are identified as prerequisites for sustainable development and as means of strengthening the global competitiveness of African producers.

But significant institutional challenges persist. While progress is being made under the industrial pillars of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), negotiations on raw materials remain particularly sensitive. Moreover, the AMDC, whose mandate is to support the implementation of continental strategies and related instruments, has not yet been fully ratified; thus, there is no access to regular AU budget funding. At least 15 AU member states must ratify the establishment of the centre; as of the end of 2025, only four of the 55 members of the AU had completed that process – Nigeria being the last to do so and major continental mining producers such as Ghana and South Africa still not having voted on the issue. Overlapping initiatives – including the Africa Minerals Strategy Group (AMSG), which, launched at the Future Minerals Forum in Riyadh in 2024 (with Saudi Arabia as observer) – pursue similar objectives but operate outside formal AU institutional frameworks. As a result, continental coordination and the harmonisation of standards and operational practices remain a work in progress (as in the EU) while support to member states continues to fall short.

At the same time, the political momentum is increasingly shifting to national capitals. Governments across Africa are becoming more and more assertive. Many are advancing new critical mineral strategies to capture greater value at home through export restrictions, processing targets and investment incentives. The strategies recently published or being drawn up by Zambia, South Africa, Ghana and Tanzania reveal the characteristics of various forms of resource nationalism and balance openness to investment with stronger state intervention.

The new critical mineral strategies are primarily national in scope. Links to continental frameworks such as the AMGS are limited, and political ambition has not yet been translated into implementation through regional initiatives. The most prominent of such initiatives – the Zambia–DRC battery cluster – has attracted considerable attention but made only modest progress to date.

Navigating global competition

African governments have voiced the ambition of assuming a more influential role in global mineral governance in order to promote their industrialisation goals amid intensifying geopolitical competition.

South Africa has positioned itself as a key African champion of multilateral mineral governance. It co-chairs the UN Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals, while its G20 Presidency in 2025 marked a milestone in putting critical minerals firmly on the agenda. The Leaders’ Declaration, adopted in November 2025, welcomed the establishment of a G20 Critical Minerals Framework and explicitly addressed the priorities of mineral-producing countries, which were identified as value addition, local beneficiation and sustainable mining. At the same time, the document recognised the supply security concerns of import-dependent economies, such as European member states.

Translating political commitments into favourable industrial outcomes for African producers remains a complex undertaking. Structural constraints – most notably, those restricting access to capital and technology – continue to reinforce the asymmetry of global market relations. In addition, high investment needs in the area of infrastructure development (especially transport and energy), which are crucial not only for mining operations but also for downstream projects and industries, often exceed domestic capacities to provide such funding, leaving African governments reliant on external partners.

But contrary to what many European policymakers still believe, African governments are not idly waiting for European offers in the mining sector. Interest in the continent is high among both long-standing and new partners and investors, with the latter moving quickly to secure their strategic interests. China continues to consolidate its dominant position, with the main goal of ensuring access to minerals and maintaining its global industrial lead. Gulf states are significantly expanding their resource diplomacy and acquiring strategic mining assets, while India and Turkey, among others, are increasing their mining and manufacturing footprint. For its part, the US under Trump is pursuing a distinctly transactional and bilateral approach, grounded either in political trust in and support from the US government or in the use of coercive tools such as tariffs; overall, with limited value for building long-term industrial partnerships.

African governments are keenly aware of the strategic interests of those driving this external engagement. Rather than favouring one partner over another, most governments are seeking to navigate the competing bids in the minerals sector by choosing external actors based on their ability to deliver tangible investments and concrete industrial outcomes.

Ambitions and constraints of EU raw material cooperation

At first glance, the EU appears well positioned: African governments remain open to new partners, and both sides are interested in more sustainable and resilient mineral value chains. On closer examination, however, it is evident that priorities differ: the EU’s focus is on supply security and industrial resilience, while African governments emphasise investment and industrial development. The two agendas are not incompatible and the foundations for cooperation are in place. The key challenge lies in strengthening the execution and delivery of cooperative projects.

Partnerships and projects

Since 2021, the EU has significantly expanded its engagement in the mineral sector. The CRMA, adopted in April 2024, anchors Europe’s strategy for reducing dependencies and diversifying supply chains by explicitly recognising the need for external partnerships with mineral-rich countries.

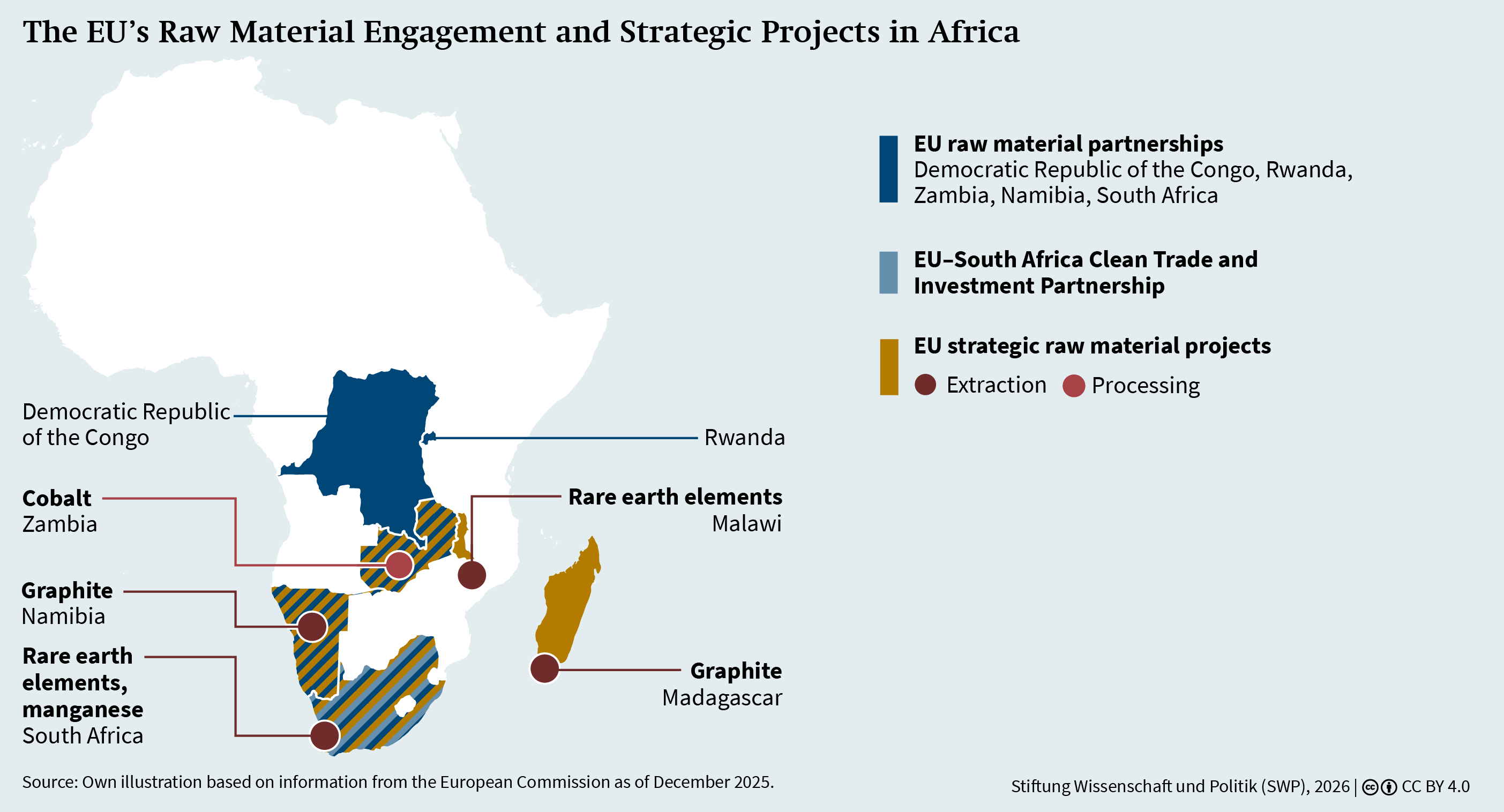

To date, the EU Commission has concluded 15 official CRM partnerships with countries around the world, including five African states: Rwanda (currently paused), the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zambia, Namibia and, more recently, South Africa (see Figure 1). At the same time, the EU is exploring a Clean Trade and Investment Partnership (CTIP) with South Africa, which is intended to facilitate industrial cooperation. And it continues to conduct a structured dialogue with the AU.

These initiatives have increased EU visibility in the mining sector on the African continent. The uniform template used for all CRM partnerships commits to cooperation across five areas: 1) supply-chain integration, 2) infrastructure financing, 3) research and innovation, 4) capacity-building and 5) sustainable and responsible sourcing. Implementation is guided by bilateral roadmaps and pursued under the Team Europe approach, whereby the EU, the individual member states and the bloc’s various institutions join forces.

In practice, cooperation has advanced most clearly in governance-related areas (3–5), where the EU has built a recognised comparative advantage. In Zambia, for example, the government values technical assistance in resource governance and environmental management. South Africa’s signature to its CRM partnership on the sidelines of the G20 summit sent a strong signal in support of multilateralism, amid heightened geopolitical tensions and the US boycott of the summit. Pretoria explicitly welcomed the EU’s commitment to support not only South Africa’s value-addition efforts but also the improved governance of CRMs.

While development-oriented instruments are well suited to deliver on governance, sustainability and capacity-building objectives, they are less effective in mobilising CRM investment and accelerating industrial projects, which is what African partners are expecting. To help close this gap, the EU has started launching its strategic raw material projects. The first such projects were announced in 2025, including five in Africa (not all of which are partnership countries). They are intended to strengthen links between African producers and European industry. As Figure 1 shows, they comprise four mining projects (in Madagascar, Malawi, Namibia and South Africa) and one refining project (in Zambia) and cover five of the CRMs included in the 2024 EU’s list of 13 strategic raw materials.

While the launch of these projects is an important step forward, the overall impact remains limited. To date, EU engagement has been confined largely to isolated flagship projects. The bloc needs to develop a more proactive and coordinated external project pipeline, rather than continuing to rely on the lengthy application-based procedures followed until now. More important, project support – particularly funding for private-sector engagement – remains slow in materialising and limited in scale, constraining the effectiveness of the EU strategy.

State-business relations

The EU’s approach to critical raw materials remains market-based and relatively cautious. As a result, its ability to deliver concrete projects is lagging that of more assertive actors in what is a strongly competitive CRM market.

China – notably through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – follows a state-led model that combines diplomatic support, state-backed finance and infrastructure investment to secure long-term offtake for its downstream industries. Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), are rapidly expanding their footprint through sovereign wealth funds and strategic investments across mining and infrastructure sectors. And the US under Trump has stepped up its intervention, too, and is now deploying substantial public funds. In October 2025, the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) entered into a US$1.8 billion investment consortium with two international investors (one from Abu Dhabi). Closer US–Gulf cooperation in Africa had already been anticipated, with early consortium interest focused on a potential stake in a Glencore DRC mining asset. In February 2026, Washington launched the FORGE alliance, proposing a preferential trade zone and exploring price floors. This may accelerate US-backed projects in Africa, under “America First” priorities and conditioned by political relations with the US government, while likely to prioritise extractive projects.

In Europe, CRM projects and the construction of related infrastructure continue to depend mainly on voluntary private-sector engagement. European corporates have long tended to rely on market mechanisms while investment in overseas mining remains limited, with significantly higher levels from France than Germany. Despite growing geopolitical pressure to diversify mineral supply chains, this dynamic has not changed fundamentally. Private-sector engagement, particularly in upstream mining, still falls short of political expectations. There are several structural factors constraining engagement: equity stakes in mining projects are extremely capital-intensive, they require long-term commitments and they also entail high commercial and reputational risks. As a result, such investments are feasible only for a small number of firms. Furthermore, both real and, in some cases, exaggerated risk perceptions weigh heavily on Africa as an investment destination. The business-to-business relationships between local and European companies remain small in number. Indeed, hesitation was evident from the limited participation of European firms in the Lobito business forum in Zambia in late 2025, which were aimed at attracting interest in the local mining sector.

At the same time, long-term engagement is crucial. Opportunities to diversify mineral supply chains are structurally constrained: markets for critical minerals are often highly concentrated and offtake agreements secured – largely in favour of Chinese buyers at present.

Although the EU is Africa’s most important trading partner overall, it plays only a small role in the continent’s mineral sector. Mineral trade flows are difficult to follow owing to their complexity, but the available data point to still small volumes of critical mineral exports to Europe. South Africa is an exception of sorts, particularly in the supply of platinum group metals and owing to its relatively larger industrial base. Elsewhere, value-chain integration between the two continents remains underdeveloped, highlighting the importance of effective project delivery for mineral cooperation.

The Global Gateway gap

A dedicated and well-coordinated external financing architecture is not provided for in the CRMA. As a result, the EU’s ability to support cooperation with African partners in a strategic and efficient manner continues to be restricted. Despite early calls for an EU-level raw materials fund and integrated instruments that would combine public finance and de-risking tools for projects with technical assistance, there has been little commitment in this regard. For this reason, external engagement continues to rely on a fragmented set of existing instruments.

In practice, the EU’s external engagement over CRMs on the African continent is channelled through the Global Gateway, launched in 2021 by the Von der Leyen Commission as the EU’s global infrastructure and connectivity initiative. The Global Gateway does not constitute a single financing instrument; rather, it brings together EU tools – notably, the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+) – and financial contributions from member states under the Team Europe approach. By crowding in private investment, the initiative initially aimed to mobilise €300 billion between 2021 and 2027, including €150 billion for Africa. In October 2025, the Commission announced that the overall target had already been exceeded.

In its current institutional design, the Global Gateway is difficult to operationalise as an effective and strategic instrument. Diffused responsibilities within the EU and its member states, combined with unclear access modalities for the private sector, are complicating factors for coherent implementation. Significant gaps remain in the areas of project-pipeline transparency, project delivery and the mobilisation of private capital.

Moreover, integrating the raw material agenda into the Global Gateway proved challenging from the outset. When the CRMA was adopted in 2024, the EU’s current Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) was already halfway through its seven year mandate (2021–27) and most Global Gateway–related budgets had already been allocated, limiting the scope for the funding of additional projects. While some flagship initiatives have been launched – including the Lobito Corridor as an enabling infrastructure project in Southern Africa – the EU has yet to translate political ambition into concrete CRM projects with higher private-sector involvement.

Future delivery of such projects hinges on the allocation of dedicated financial resources and thus on the negotiations over the next MFF (2028–34), which are set to intensify in 2026. In July 2025, the EU Commission proposed consolidating its external action instruments into a €200.3 billion “Global Europe” instrument, with geographically oriented pillars. Although €60.5 billion was earmarked for Sub-Saharan Africa, those funds have to cater to competing priorities that range from migration to humanitarian assistance. Thus, the sum is unlikely to prove sufficient to meet the scale required for comprehensive CRM engagement.

The EIB will play a decisive role in the European external CRM engagement. Its impact will be greatest if it acts not merely as a technical financier but as a strategic actor. Its willingness or clear mandate to engage in high-risk, capital-intensive projects outside the EU will be central to the credibility of Europe’s diversification efforts and its CRM partnerships in today’s highly competitive global environment. In March 2025, the bank adopted a Critical Raw Material Strategic Initiative, signalling its increased engagement along the value chain, and announced an annual spending target of €2 billion for the sector. Those funds are likely to account for a major part of the €3 billion announced under the RESourceEU Action Plan in December 2025. Just how much financing will ultimately be available for non-EU projects remains uncertain, however.

Given the limited resources within the EU, more effective coordination is essential in order to maximise impact. The EU has taken initial steps towards institutional innovation. The Global Gateway Investment Hub is intended to function as a single-entry platform for companies. They shall submit investment proposals through government-led “Team Nationals” platforms, aiming to ensure aligning projects with EU and partner priorities while maximising coordinated national and European support. Effective coordination and collaboration is essential due to account for the realities of the raw material sector. Capital-intensive mining projects involve high risk and require multi-billion euro financing packages, as illustrated by Vulcan Energy’s lithium project in Germany, which relies on a multi-actor financing package of around €2 billion.

At the same time, access for firms to EU financing is challenging, particularly for non-European firms, as requirements and due-diligence procedures are rigid and complex, and support limited in scale. That situation could be remedied, at least in part, through the closer coordination between EU-level instruments and member-state tools. Several member states – including France, Germany and the Netherlands – have established dedicated raw material funds that can be used to achieve complementarity, particularly in the case of large, value chain-integrated projects and major infrastructure corridors. Uncoordinated national initiatives risk undermining the EU’s credibility. Italy’s €320 million pledge to the Zambian part of the Lobito Corridor, which was made outside the established coordination channels, exemplifies how unilateral action can weaken EU collective visibility and delivery.

Finally, proposals for enhanced coordination under the Global Gateway highlight the need to more closely integrate export credit agencies (ECAs) into the initiative. If tasked with earlier engagement and active risk-sharing, ECAs can add value by de-risking capital-intensive raw material projects. For its part, Germany offers relevant experience with its untied loan guarantees (UFKs), which could be leveraged more systematically. In 2024, there were 14 such guarantees in place, with just one other being approved during that year. Thus, the available coverage capacity is still far from being fully utilised.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The AU-EU Summit in November 2025 confirmed that there is a large degree of political alignment in what is becoming an increasingly fragmented global order. Critical raw materials featured prominently on the agenda of the summit, reflecting the important role these commodities play in geoeconomic competition and the industrial strategies of the two continents. There is a clear overlap of interests in Africa’s ambition to leverage mineral resources for industrial development and Europe’s need to diversify and de-risk supply chains. At a time when multilateral cooperation can no longer be taken for granted, resilient mineral supply chains demand credible partnerships. The structured dialogue with the AU, combined with the bilateral CRM agreements and the launch of the first strategic projects, provides a solid institutional foundation for such partnerships. Accelerating project delivery and scaling up industrial projects are the main tests of the EU’s credibility as a partner in today’s highly competitive environment.

For its part, the EU needs to ensure that Africa is anchored more firmly in its raw material strategy. It must also shift away from its development-oriented approach and instruments. While technical assistance remains an important component of the European CRM offer, in areas such as mineral governance, standards and capacity building, CRM partnerships are increasingly being driven by industrial and geopolitical considerations. The work of the Directorate-General for International Partnerships (DG INTPA) within the framework of bilateral CRM partnerships is important but cannot, in itself, constitute the primary organising logic of EU CRM engagement on the African continent. Depending on institutional capacity, the stronger involvement of industry-, trade- and energy-focused portfolios, particularly that of the Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (DG GROW), is essential. This would not only strengthen industrial cooperation and integrate technical and market expertise; it would also ensure greater strategic coherence across the EU’s external actions.

There are three main requirements for putting such a shift into practice. First, more robust external project pipelines must be developed and jointly defined. Building on continental frameworks such as the AGMS, project pipelines drawn up with African partners and supported by African financial institutions would improve alignment with African industrial priorities while responding to Europe’s supply-security objectives.

Second, project delivery depends on the availability and strategic use of finance. For this reason, CRM cooperation needs to become a more integral part of the EU’s external financing architecture and embedded in the next MFF, including through dedicated budgetary lines and the expanded use of blended finance for projects along mineral value chains and enabling infrastructure. This should be complemented by greater transparency regarding the EIB’s RESourceEU commitment – in particular, the extent of its risk appetite and the scope of support for projects in African partner countries. At the same time, there should be no delay in enhancing coordination within the Global Gateway framework, with the aim of improving systematic coordination between EU institutions and member states and, crucially, strengthening the role of national ECAs in addressing the high-risk, capital-intensive nature of CRM investments.

Third, European companies are essential for project delivery. In particular, downstream offtake agreements are needed to provide long-term demand certainty and underpin public investment decisions. While public support remains vital in the current geoeconomic environment, companies must assume greater responsibility for building resilient mineral supply chains that support Europe’s industrial competitiveness going forward.

Within Team Europe, Germany can play a reinforcing role by advocating a stronger anchoring of the CRMA in the next MFF and supporting more coherent Global Gateway coordination with Brussels, under the leadership of the Foreign Office. The contribution of the respective line ministries should be clearly defined: the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development should expand support for external project pipelines and technical assistance, while the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy should strengthen external economic instruments, including UFKs, and embed Germany’s raw material policy in a coordinated European approach.

Meike Schulze was a Research Associate at the SWP until December 2025. She currently works as a freelance political scientist and consultant. This SWP Comment was prepared as part of the 2024–25 project “International Raw Material Cooperation for Sustainable and Resilient Supply Chains”, which was funded by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2026C07