Mounting Pressure on Russia’s Government Budget

Financial and Political Risks of Stagnation

SWP Research Paper 2019/RP 02, 08.02.2019, 44 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2019RP02

Research AreasDr Janis Kluge is a Senior Associate in the Eastern Europe and Eurasia Division at SWP.

Economic stagnation and demographic change in Russia are putting intense pressure on the government budget. Tax revenues have been declining since the late 2000s. Meanwhile, the oil dependency of Russia’s budget has increased significantly. This became patently clear when the oil price plummeted in 2014. Energy revenues have since begun to recover, but the Finance Ministry’s reserves have shrunk considerably and are only slowly being replenished.

To keep public budgets stable, the Russian government is forced to raise taxes and extend the retirement age in the years to come. There is a widening gap in funds required to cover the paternalistic social policies of earlier years. At the same time, the struggle for control of public resources is having a destabilizing effect on the political regime – especially in light of the ever more pressing question of Putin’s successor in the Kremlin.

Up to the presidential election of 2018, the Russian leadership avoided making any budget cuts that would have hurt key clientele groups: retirees and the military-industrial complex. Additional income was generated instead through a series of smaller budgetary adjustments. Shortly after the start of Putin’s fourth term, however, tax raises and a higher retirement age were announced, which lead to drastic declines in the president’s approval ratings.

As a reaction to shrinking funds, budget policy is now being controlled in a more centralized way by Moscow, while public oversight of government budgets has been restricted. Shadow budgets have also emerged outside the purview of the finance administration. In this complex and politically tense situation, conflicts between elites are erupting with increasing frequency, bearing risks for Putin’s fourth term in office.

Table of contents

Mounting Pressure on Russia’s Government Budget

2 Diminishing Room to Manoeuver

2.1 It’s not just the oil price

2.1.1 Effects of possible US s anctions on Russian government bonds

2.2 Russia’s hidden liabilities

2.3 Volatile oil price putting a strain on budget discipline

2.3.1 Fiscal Rules Volatile oil price putting a strain on budget discipline

3.1 Social and pension policy is becoming more expensive

3.1.1 The informal sector impedes targeted redistribution

3.1.2 Pensioners benefit from redistribution

3.1.4 Pensions increase oil dependence

3.1.5 Regression instead of reform

3.2 Defense expenditures are top priority

3.2.2 The risks for the arms industry

3.2.3 No change of course up to now

3.3 Russian discourse: Concepts without consequences

3.3.1 Kudrin’s fiscal manoeuver

3.3.2 The Stolypin Club’s “strategy of growth”

3.3.3 Low likelihood of implementation

4 Contested Control over State Finances

4.1 Undermining the separation of powers

4.2 Highlights and lowlights of transparency

4.3 Bypassing the budget: Public funds in state-owned companies

4.3.1 Dividends: Insubordinate energy companies

Issues and Conclusions

Mounting Pressure on Russia’s Government Budget: Financial and Political Risks of Stagnation

Russian budget revenues relative to GDP have declined substantially over the last decade. The lower oil price is one reason for this, but tax revenues outside the energy sector have fallen as well. The Russian economy has been in a period of stagnation for a number of years now, placing a burden on state coffers. The government reserves that the Kremlin was still able to fall back on prior to the 2009 financial crisis have been largely exhausted in 2015 and 2016, and economic growth is expected to be slow after 2018. The Russian leadership faces ongoing financial difficulties in the years ahead, making unpopular policies such as increasing the value added tax and raising the retirement age necessary.

At the same time, the domestic political situation has become more difficult for the Kremlin to manage. Without economic growth, the Russian leadership will no longer be able to fulfill its implicit “social contract” with the population. As long as the standard of living was rising, the vast majority of Russian citizens refrained from active participation in politics. But then from 2014 to 2017, real incomes fell for four years running. The Kremlin could now be facing a crisis of legitimacy – and that in a phase of uncertainty about a possible shift of power after Putin’s last term of office (2018–2024).

Will the Russian regime be able to adapt to the changing economic reality, or will dwindling resources lead to a destabilization of the political system? How is the Kremlin dealing with the increasing pressure to implement economic reforms? Are any practical ways to escape the budgetary dependence on oil revenues beginning to emerge, or will the risks increase further in the years to come?

After the oil price collapse of 2014 put the state budget under pressure, the Kremlin pursued policies aimed at maintaining the existing political and economic order. Rather than undertaking important but risky reform projects in the run-up to the 2018 presidential election, the leadership in Moscow sought to mobilize remaining reserves in the system by implementing a series of smaller budget and tax adjustments. In doing so, it sought to keep the financial and political risks resulting from budgetary policy in check. This changed with Putin’s inauguration, shortly after which tax increases and a higher retirement age were announced, which have led to drastic declines in the president’s approval ratings.

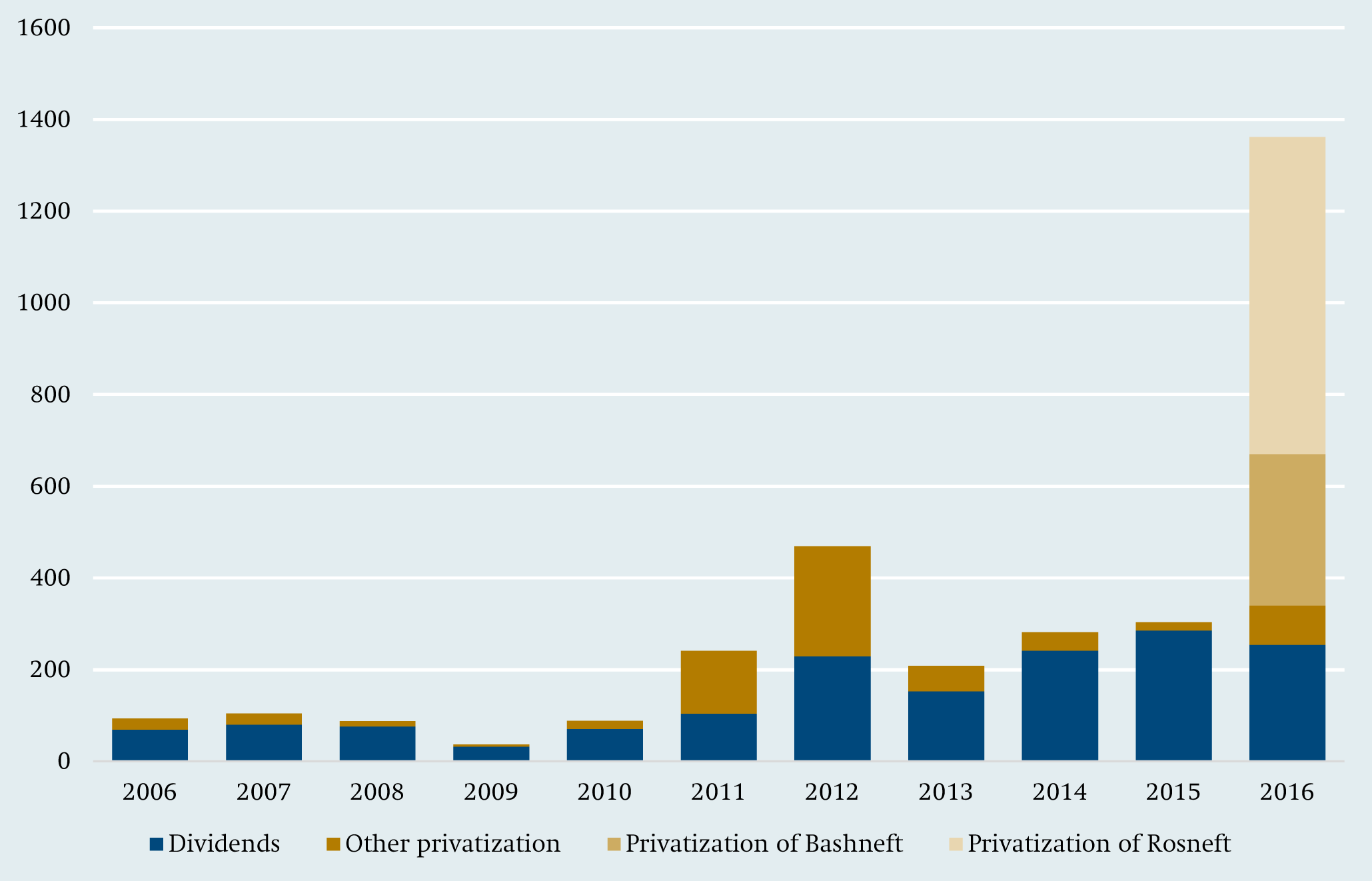

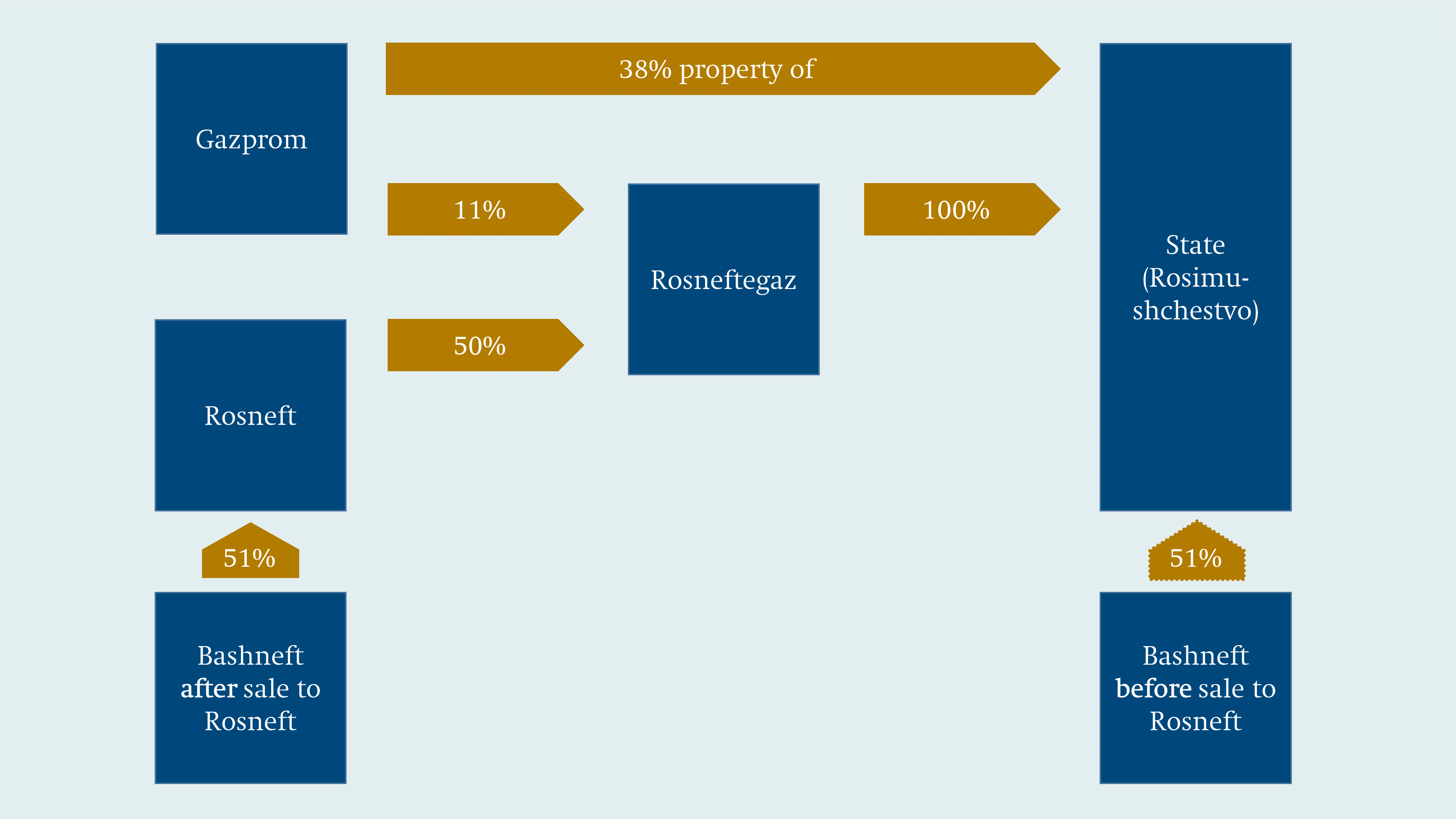

To increase revenues at the height of the economic crisis in 2016, the Russian government sold shares in the oil companies Bashneft and Rosneft but without relinquishing control over them. The state pension system discontinued capital accumulation so that all premiums could be used to cover the pay-as-you-go pensions. Russia’s commitment to oil output cuts, in line with the November 2016 resolution of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), was also aimed at increasing revenues without engaging in structural reform within the country.

On the spending side, Russia’s leadership has distinguished between politically risky and less risky areas. It has passed early and significant budget cuts in policy areas that did not affect the Kremlin’s core voters and supporters – areas like education, the economy (infrastructure), and health spending on the federal level. Pensions, social security, and defense, on the other hand, have long been spared from budget cuts.

Only when the 2016 budget crisis reached dangerous proportions did the Russian government decide to reduce pension inflation adjustments and eventually also raise the retirement age. The Kremlin’s approach to military spending was similarly cautious: Decisions on a long-term state armament program were delayed repeatedly and finally made in fall of 2017, only after the oil price had recovered to some extent.

The increased pressure on the government budget has exacerbated conflicts over the distribution of financial resources, heightening the importance of control over the remaining funds. This has led, among other things, to a centralization and personalization of decision-making power over budgetary funds in the Kremlin. Other political actors like the State Duma have not played a significant role in the budget process for years now. The already low scope of action available to regional government administrations has been curtailed further in recent times.

The Russian leadership is not only further weakening the Russian federalist system through centralization, but also undermining the binding nature of budgetary planning itself. Budget plans have become more opaque and unspecific, and resources that lie outside the Finance Ministry’s purview have increased. The big state-owned enterprises play an important role in this: they only pay part of their profits into the state’s budget, and in return, they take on direct political responsibilities in Russia and abroad. Public control over government resources is thus being gradually eroded and the directors of the state-owned enterprises are becoming influential political figures with their own agendas.

From the perspective of Germany and the EU, the vulnerability of Russia’s government budgets has important political implications. In a situation of declining government revenues, the Russian regime will have a difficult time legitimizing its rule by pointing to economic successes or instituting comprehensive social programs. The regime’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 garnered high approval ratings in 2015 and 2016 despite the economic slump. If a loss of legitimacy becomes an imminent threat, the Russian leadership could be tempted to build on this experience. The result would be a stronger emphasis on mobilizing patriotic sentiment and intensifying anti-Western propaganda. An improvement in relations between the EU and Russia would then be pushed off into the more distant future.

A more prolonged budget crisis or a serious de-stabilization of the Russian regime could also have severe immediate impacts on the EU. For Germany, it would pose risks to the energy supply and to the security of foreign direct investments in Russia. Political destabilization in Moscow would also quickly spread to neighboring countries with close economic ties to Russia. Unresolved conflicts in the region could then spin out of control.

Diminishing Room to Manoeuver

Russia’s public budgets are comprised of the federal budget (with spending of 17.8 percent of GDP in 2017), regional and municipal budgets (11.7 percent), and the social security funds (11.6 percent).1 In absolute figures, federal spending in 2017 was 16.4 trillion rubles (€249 billion2) and consolidated expenditures for all public budgets amounted to 32 trillion rubles (€485 billion). Since all of the various government budgets are interlinked through extensive transfers, total government spending (that is, the government spending ratio) adds up to 35.2 percent of GDP. In the broadest sense, government-controlled enterprises also belong to the public sector. Only estimates are available as to these companies’ expenditures. Studies by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Russian economists estimate them at 29 to 30 percent of GDP.3

It’s not just the oil price

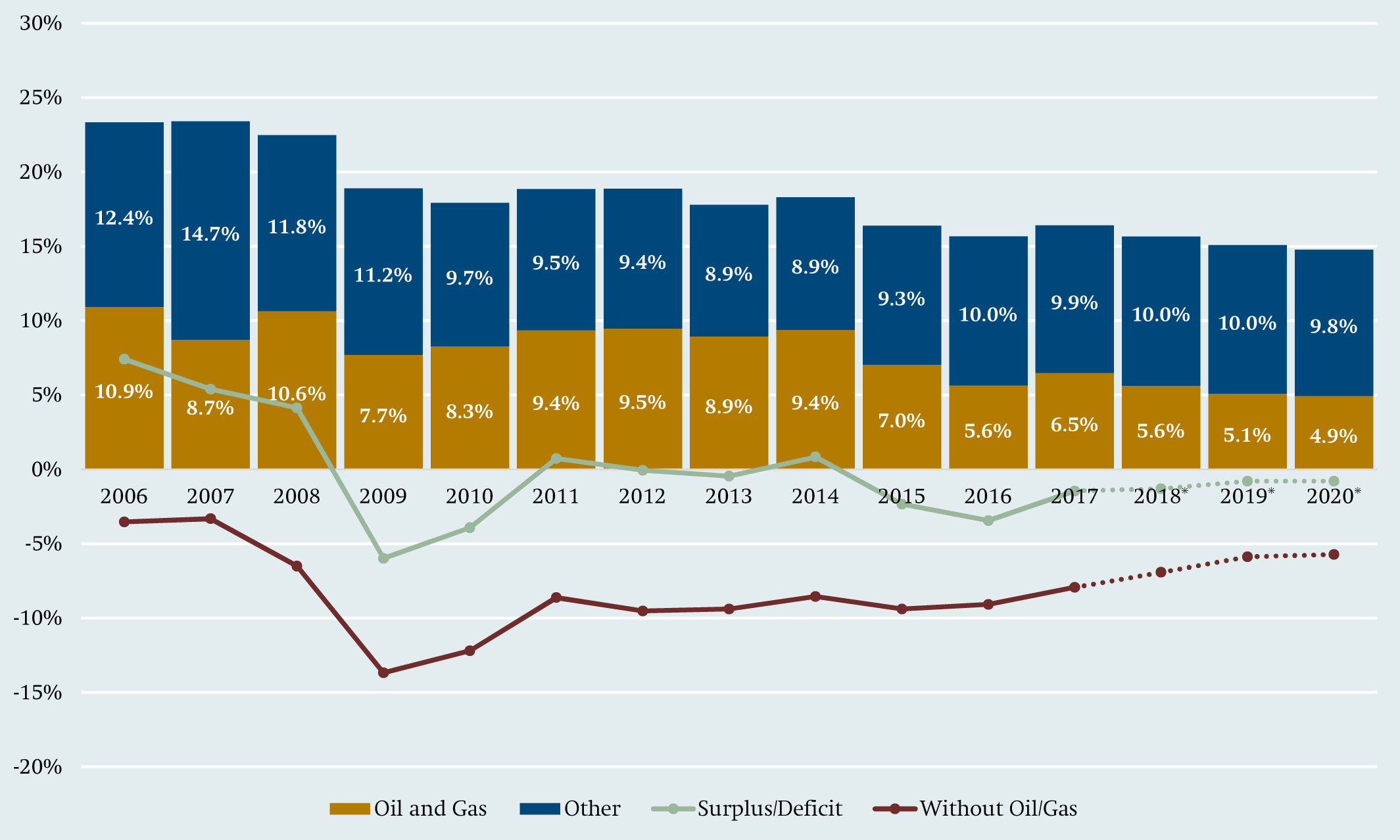

Oil and gas extraction taxes and export tariffs have made up around half of all federal and a quarter of total tax revenues in Russia since the mid-2000s (see Appendices A and B, p. 42 and 43). During the oil boom of 2010–2014, annual revenues from oil and gas sales amounted to 9 percent of GDP. At first glance, this does not seem to place Russia in the category of “rentier states”, which derive the lion’s share4 of their tax revenues from sales of oil and gas. In Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Iraq, energy revenues make up over 80 percent of the total government budget.5 In Russia, however, non-oil tax revenues depend in part on energy exports as well. Energy companies play an important role, for instance, in corporate and individual income taxes. Taken at face value, the budget figures also conceal the fact that domestic gas supply is cross-subsidized in the Russian economy by revenues from gas exports.6

The oil price slump of 2014 had a severe negative effect on federal tax revenues. Although the floating of the ruble exchange rate absorbed some of the shock, revenues fell by more than one third up to 2016 to just 5.6 percent of GDP, which resulted in a federal budget deficit of 3.4 percent of GDP. Without two major privatizations (Rosneft and Bashneft), the deficit would have been as high as 4.6 percent of GDP in Diminishing Room to Manoeuver

|

Figure 1 Federal budget revenues and balance (in percent of GDP) as of May 2018 |

|

Budget planning figures were used for the years 2018–2020. At the end of May 2018, a new budget bill was introduced in the Russian Duma taking the sharply increased oil price from 2018 into account. As a result of this, revenues are 1.8 percent of GDP higher, and instead of a deficit of 1.3% percent of GDP, a surplus of 0.5 percent of GDP is expected, Gosudarstvennaya Duma Federal’nogo Sobranija Rossijskoj Federacii, Zakonoproekt № 476242-7 [draft law no. 476242-7], 29 May 2018, http://sozd.parliament.gov.ru/bill/476242-7. Source: Minfin Rossii, Finansovo-ėkonomicheskie pokazateli Rossijskoj Federacii [Financial and economic indicators of the Russian Federation], https://www.minfin.ru/ru/statistics/ |

The reduced revenues from oil and gas sales are responsible for just part of the current budget imbalance. Revenues from other areas have been in decline for several years now. This is true especially of corporate and individual income taxes, which made up 10 percent of GDP in 2008 but just 6.2 percent of GDP in 2013 (before the oil price drop). Since these taxes accrue mainly to regional budgets, the regions’ debts increased substantially over this period. The situation was exacerbated further in 2012 after Vladimir Putin laid out goals for his third term of office in his May Decrees that placed a heavy strain on regional budgets.8 Pay increases for civil servants played a significant role in this. The risks of regional debt are ultimately borne by the federal budget. Regional debt is distributed extremely unequally across Russia’s regions, but is low overall at just 2.4 percent of GDP.9

The decline in non-oil revenues in the remaining budget balance up to 2014 was disguised by the boom in commodity prices. It only became evident in the non-oil deficit, an indicator published by the Russian Finance Ministry for the Russian budget’s oil dependence. This budget deficit is hypothetical: tax revenues from oil and gas have been deducted from it. For 2007, the non-oil deficit was still 3.3 percent of GDP; since the financial crisis, the budget deficit would have been between 9 and 10 percent of GDP without oil and gas revenues in most years.

Economic growth is unlikely to ease budgetary strain in the years to come.

According to estimates by Fitch Ratings, Russia would have needed an average oil price of $72 a barrel in 2017 to balance its budget. This places Russia in the middle among the world’s major oil-exporting nations: Nigeria ($139), Bahrain ($84), and Angola ($82) needed much higher prices. Kuwait ($45), Qatar ($51), and the United Arab Emirates ($60) adjusted better to the lower oil price. Like Russia, Saudi Arabia was in the middle of the field in 2017, at $74 per barrel.10

Economic growth is unlikely to ease the strain on budgets in the years to come. The Russian economy posted 1.5 percent growth in 2017,11 allowing it to leave the recessions of 2015 and 2016 behind. Yet forecasts for the coming years are less optimistic: growth rates are projected to be 1.7–1.8 percent up to 2020.12

The background to Russia’s current long-term economic slump is a significant decline in potential growth since the 2000s that is rooted in structural problems. Despite high potential returns on investment, large amounts of capital are exported and too little is invested in Russia. Private businesses have a difficult time in many sectors due to the lack of reliable property rights protections. The major state-owned enterprises, whose share in the Russian economy has increased even further in recent times, are less efficient than private businesses.13

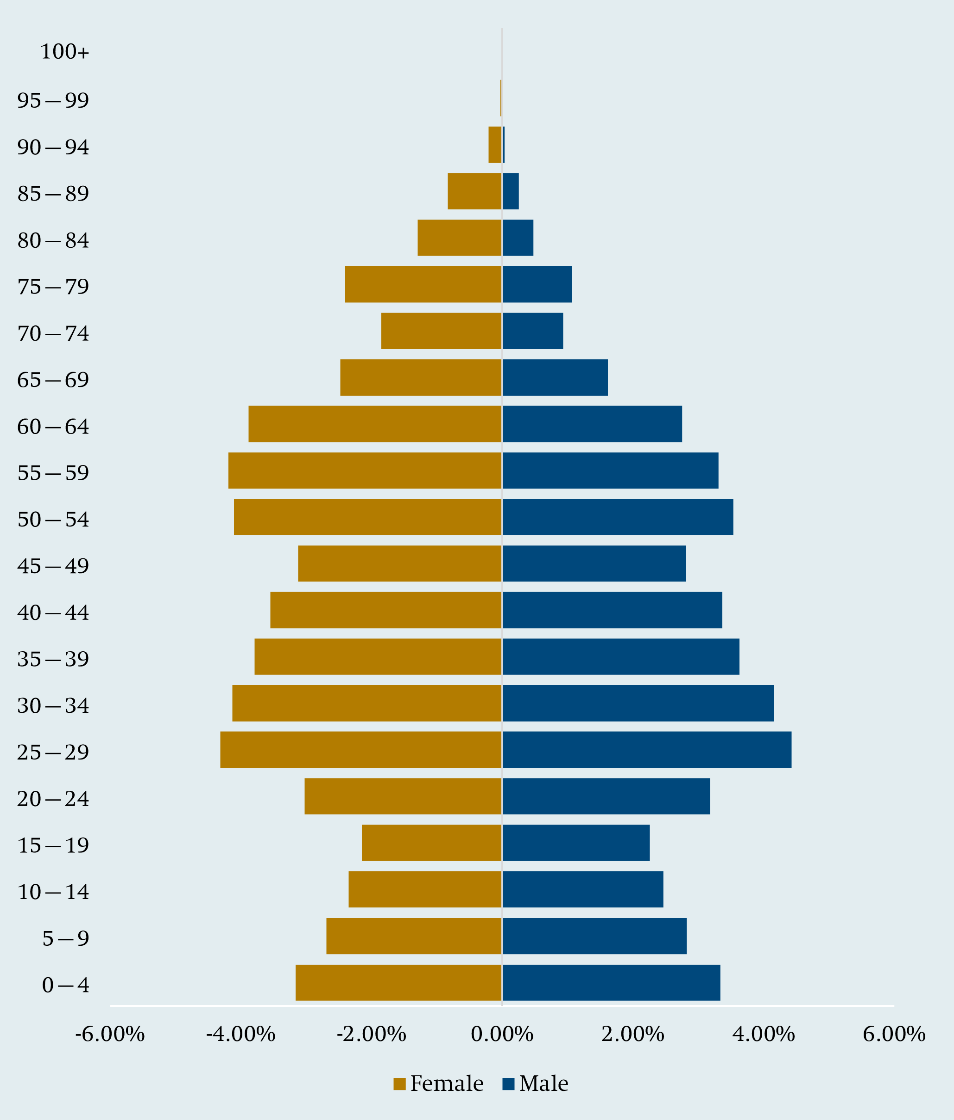

The difficult demographic situation in Russia at present is putting an additional damper on growth. Around one-third of economic growth from 1997 to 2011 came from the “demographic dividends” of a growing working-age population – an extraordinarily favorable situation.14 What had once been a blessing increasingly became a curse, however: in 2017 alone, Russia’s working-age population dropped from 84.2 to 83.2 million. A large cohort is currently leaving the labor market, while the cohort of young people entering the workforce is just half as large. Up to 2024, the Russian statistical office Rosstat expects a further decline to a working-age population of 77.9 million.15

Western sanctions are also having a negative impact on Russia’s prospects for the future. The immediate effect of the financial market sanctions imposed by the EU and USA during the crisis in the Ukraine peaked in late 2014 and 2015, but new risks arose in the summer of 2017 with the United States’ CAATS Act (Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act), which is severely affecting Russian companies with international business ties. Uncertainty about the future use of the various sanction mechanisms mentioned in the act is impeding the Russian economy’s integration into international supply chains and access to Western capital markets. This in turn raises protectionist walls higher that were erected around the economy by Russian industrial policy from 2012–2018 during Putin’s third term of office.16

|

Figure 2 Russian Population by Age Groups (2015) |

|

Source: Diagram by author based on data from the United Nations, World Population Prospects 2017, |

Diminishing Room to Manoeuver It’s not just the oil price

|

In the framework of the United States’ Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in 2017, the Treasury Department was directed to submit a detailed report on the consequences of the United States imposing sanctions on Russian government bonds.a If the US president sanctioned existing government bonds, both eurobonds (a bond denominated in a foreign currency) and government bonds denominated in rubles (Obligatsii Federalnovo Zaima, OFZ) would no longer be tradeable by foreign investors after a transitional period. The Russian government’s eurobonds had a total value of $49.8 billion in early 2018, one-third of which was held by non-resident investors ($15.1 billion). The total value of the OFZ was 6.8 trillion rubles (€103.5 billion), although bonds with a volume of 2.3 trillion (€35.4 billion) were held by foreigners.b If sanctions were imposed on existing Russian government bonds, many foreign investors would have to sell their holdings quickly. As a result, more capital would flow out of Russia and the ruble would come under downward pressure. Estimates suggest that the ruble would depreciate by around 10 percent,c accompanied by higher rates of inflation.d Returns on Russian government bonds would also increase, although the |

Head of the Central Bank of Russia, Elvira Nabiullina, estimated that this effect would be 0.3–0.4 percent. Other estimates predict a much larger increase of 2 percent. In 2017, returns fluctuated between 7.5 and 8.5 percent.e In its 2018 report on this sanction mechanism, the US Treasury warned of much stronger repercussions that could even go as far as destabilizing Russian financial markets. The report focused, however, on a more benign variant that would only impose sanctions on new bonds issuance. Yet even in this case, if investors reacted to the potential sanctions with preemptive caution, the results could affect current bond holdings as well.f In the short term, the effects of the sanctions would be clearly palpable in Russia, but the potential for new domestic borrowing would not be threatened. The Central Bank has announced that in the case of a sell-off by foreign investors, it would intervene by purchasing bonds. The Finance Ministry is also working to reduce its vulnerability to sanctions by issuing its first bond on China’s capital market and by issuing what are known as “people’s bonds”, government federal bonds for private individuals in Russia.g |

|

|

a “Minfin Rossii ne stanet forsirovat’ vypusk evrobondov iz-za sankcij SŠA” [Russia’s Finance Ministry will not force the issuance of eurobonds due to US sanctions], in: Vedomosti, 18 December 2017, https://www.vedomosti.ru/finance/news/2017/ 12/18/745646-minfin-rossii-ne-stanet-forsirovat-vipusk-evrobondov-iz-za-sanktsii-ssha (accessed 26 January 2018). b Bank Rossii, Nominal’nyj ob"em obligacij federal’nogo zajma (OFZ), prinadlezhashchich nerezidentam, i dolja nerezidentov na rynke [Nominal value of foreign-held OFZ and the share held by non-resident investors], http://www.cbr.ru/ statistics/credit_statistics/debt/table_ofz.xlsx; ibid., Vlozhenija nerezidentov v evroobligacii Rossijskoj Federacii [Foreign investments in eurobonds of the Russian Federaton], http://www. cbr.ru/statistics/credit_statistics/debt/72_eurobonds.xls; Minfin Rossii, Gosudarstvennyj vneshnij dolg Rossijskoj Federacii (2011–2018 gg.) [Government foreign debt of the Russian Federation (2011–2018)], https://www.minfin.ru/common/ upload/library/2018/05/main/Obem_gos.vnesh.dolga_ |

c Danil Sedlov and Julija Titova, “Vozhidanii sankcij. Kak amerikancy mogut obrushit’ rubl’” [In expectation of sanctions. How the Americans could cause the ruble to collapse], Forbes, 21 November 2017, http://www.forbes.ru/finansy-i-investicii/353045-v-ozhidanii-sankciy-kak-amerikancy-mogut-obrushit-rubl (accessed 2 February 2018). d Tat’yana Lomskaya, “Centrobank minimal’no snizit stavku iz-za ugrozy novych sankcij” [Central Bank reduces prime interest rate minimally due to the danger of new sanctions], Vedomosti, 14 December 2017, https://www.vedomosti.ru/ economics/articles/2017/12/14/745198-tsentrobank-snizit-stavku (accessed 2 February 2018).. e For 10-year government bonds denominated in rubles (OFZ). f Erik Wasson/Saleha Mohsin, “Treasury Warns of Upheaval If U.S. Sanctions Russian Debt”, Bloomberg.com, 2 February 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2018-02-02/treasury-warns-of-widespread-effects-of-russian-debt-sanctions (accessed 5 February 2018). g Ibid.; Sedlov and Titova, “Vozhidanii sankcij” (see note c). |

|

However, for Russia, the risk of financial insolvency is currently very low. Recent western financial market sanctions also caused total foreign debt (government and private) to fall to $529.1 billion. At the same time, the Central Bank’s monetary reserves were around $449.8 billion in February 2018. Russia would be able to use these funds to pay for its current imports for 19 months.21

Russia’s hidden liabilities

It would be short-sighted to attribute Russia’s budget difficulties solely to the surprisingly sharp drop in the oil price. The budget will continue to fluctuate between deficit and surplus with the ups and downs in energy prices in the future. Long-term budget forecasts predict, however, that the surpluses will occur less often, and that the deficits will be deeper.

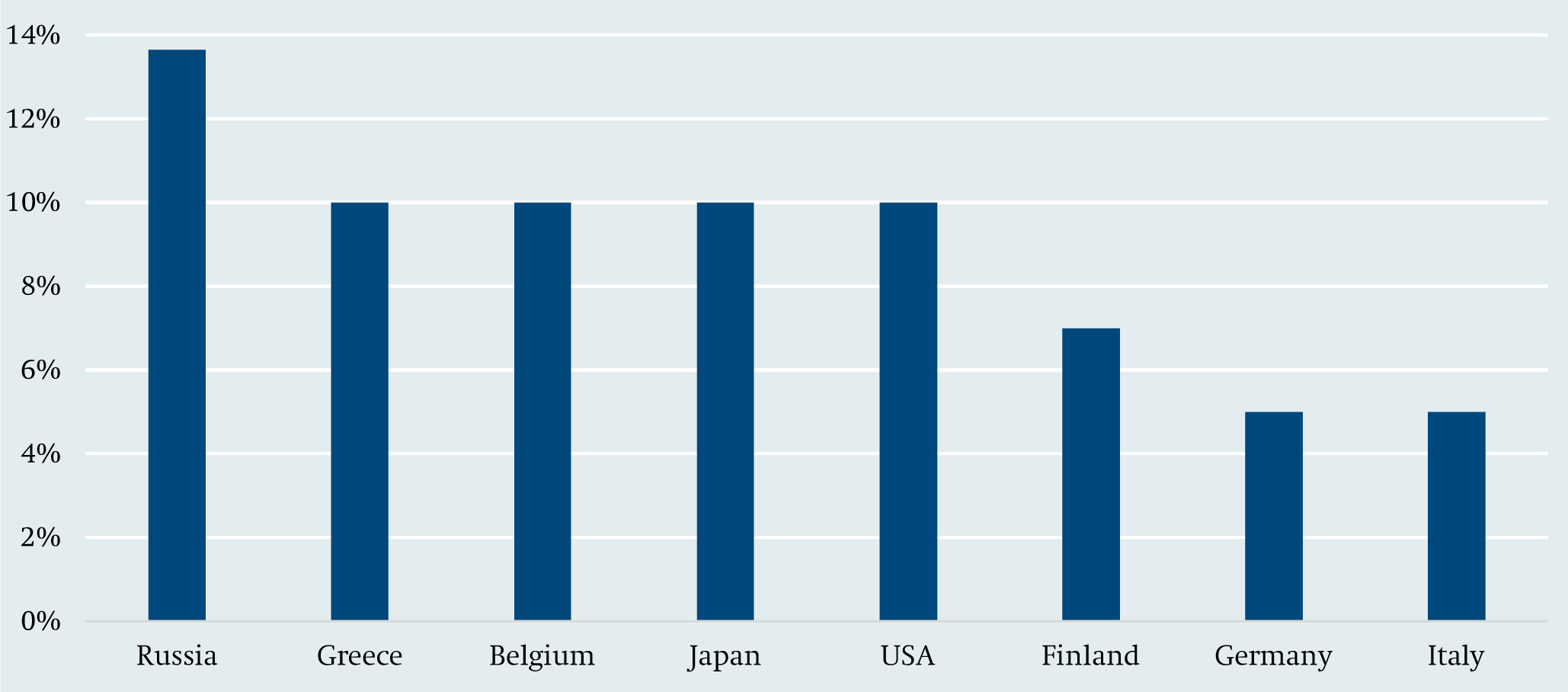

Of course, a number of parameters for long-term budget forecasts are uncertain, particularly future economic growth and commodity prices. Nevertheless, the high predictability of demographic developments allows for an approximate calculation of future burdens. Russian experts have long pointed out that the situation would worsen in the 2020s and beyond. As early as 2013, economists at the Gaidar Institute in Moscow warned that government revenues were likely to fall progressively further below expenditures in the long term.22 According to their estimates, all taxes would have to be raised by 49 percent or all expenditures reduced by 33 percent in order to balance future public budgets. Russia’s long-term “fiscal gap” of 14.6 percent of GDP per year – that is, the disparity between all future revenues and all future expenditures – is, according to the economists’ estimates, even greater than that of countries that are deeply in debt today, such as Greece, Belgium, and Japan (10 percent each) as well as Germany (5 percent).23 The gap is only gradually widening. Up to 2050, the forecast based on 2015 tax rates is an annual deficit of 11.7 percent of GDP (with expenditures increasing to 40.7 percent and revenues falling to 29 percent of GDP).24

As the financial room to manoeuver diminishes, the Russian government is forced to raise taxes and make people work longer into old age.

In comparable calculations, the World Bank estimates that Russian public debt could increase to 116 percent of GDP by 2050, although as much as 250 percent is possible depending on how productivity, demographics, and the oil price develop.25 The tax rates and pension levels assumed in these studies have already changed since Putin’s fourth term began in 2018. The studies do, however, clearly reveal what a comfortable situation the Russian treasury has enjoyed for the last 20 years. As the financial room to manoeuver continues to diminish due to demographic developments, the Russian government is being forced to raise taxes and make people work longer into old age.

Demographic change is a burden on budgets because it comes with a declining rate of employment, which causes government expenditures, especially within the pension system, to increase. Russia’s cumulative additional spending on pensions because of demographic change alone is estimated by the IMF to reach 97.9 percent of GDP by 2050.26 A similar level of reserves (instead of the close to 5 percent in the Russian welfare funds in 2018) would be required to counterbalance the impacts of demographic change on the current tax system up to 2050.

The reason for the negative forecasts is not just Russia’s demographic development, but also the predicted stagnation of oil and gas production. The World Bank expects annual oil production in Russia to fall from 547.5 million tons in 2016 to 436 million tons by 2050. At the same time, gas production is expected to increase slightly, causing Russian the value of overall energy production to remain at 2017 levels up to 2050.

It is problematic for Russia that such an important economic sector – one that was responsible for over half of Russian exports in 2017 – is predicted to show no growth. For countries that face significant demographic challenges, the solution typically centers around “growing out” of the expected burdens.

Volatile oil price putting a strain on budget discipline

For the Russian economy, the best chances of long-term growth lie outside of oil and gas. Companies outside the energy sector are much more dependent, however, on the provision of public goods. They require higher public investments than gas and oil producers, for instance, in infrastructure or the educational system. Improving the neglected economic potential outside the energy sector would therefore initially require increased government expenditures.27

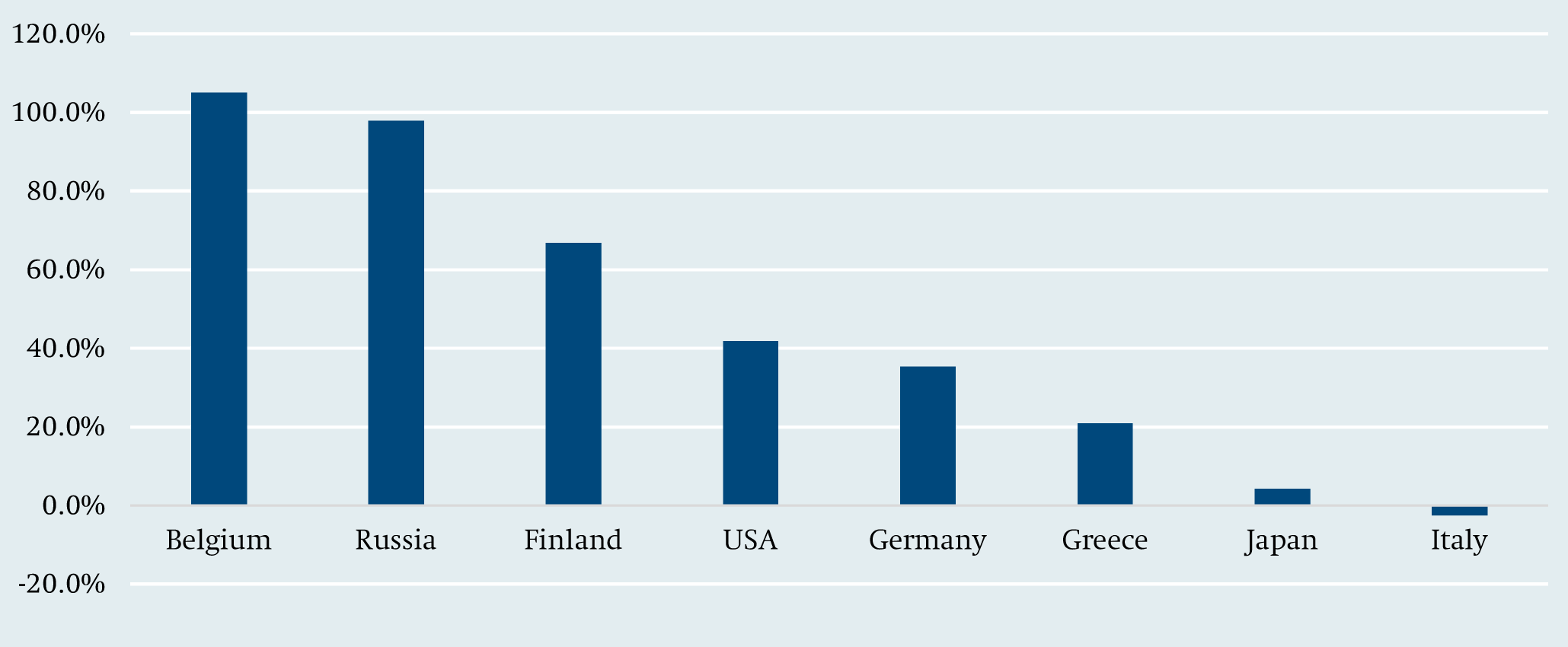

This reveals the dilemma currently facing the Russian leadership: on the one hand, major investments and possibly expensive structural reforms are needed to escape the long-term debt trap through growth. On the other hand, it is necessary to rapidly build reserves to pay for future pensions. Due to the current overall low percentage of government revenues (33.7 percent of GDP in 2017), Russia has to make more significant changes in relative terms than, for instance, Belgium (51.1 percent of GDP), which is confronted with a comparable increase in expenditures – and these changes will have a palpable impact on the Russian population.28

Volatile oil price putting a strain on budget discipline

The Finance Ministry’s reserves were the pride of Russian fiscal policy in the 2000s, but Russia’s sovereign wealth funds were never comparable in size to those of other oil-producing countries. In the United Arab Emirates, Norway, and Saudi Arabia, reserves amount to over 100 percent of GDP. In early 2009, Russian reserves reached their highest level to date at 16 percent of GDP. In 2015, just 11 percent of GDP remained. One of the two sovereign wealth funds (the reserve fund) was then used up entirely to cover budget deficits, and at the end of 2017 it was dissolved. The reserves in the second fund (national welfare fund) still made up 3.9 percent of GDP at the end

Diminishing Room to Manoeuver

|

Figure 4 |

|

Source: IMF, Fiscal Monitor, October 2013. Taxing Times (Washington, D.C., October 2013). |

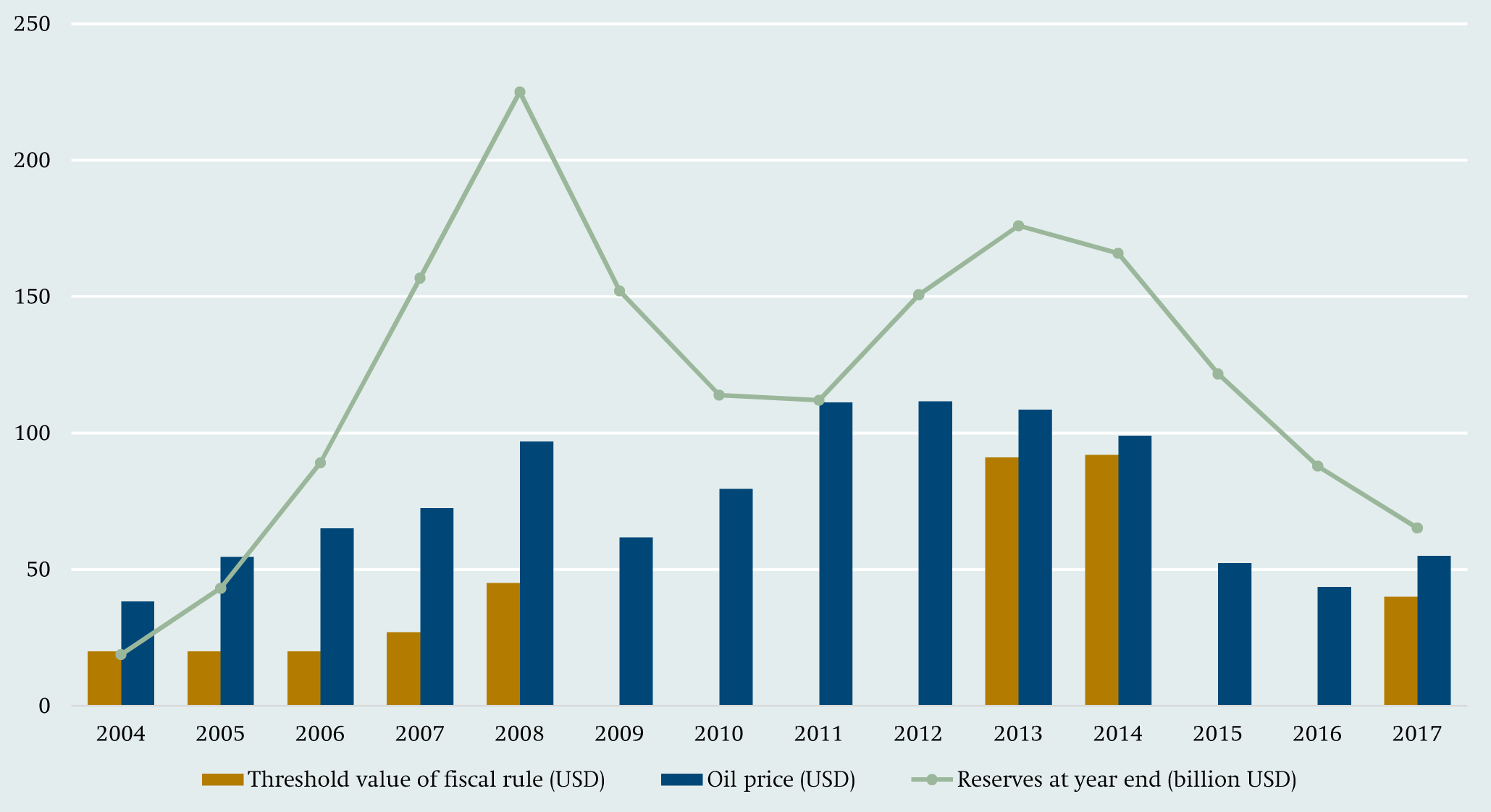

Up to now in Russia, fiscal rules have had a limited lifespan, regularly falling victim to the temptations of an expansive fiscal policy. The first fiscal rule, introduced in 2004 under then Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, stipulated that just part of the surging oil and gas revenues could be used for current spending. This freely usable part was determined by calculating revenues based on a fictitious oil price of $20: All revenues above this level had to be transferred to a “stabilization fund.” In light of the rising oil prices, the rule was weakened in the year 2007 and a new threshold value of $27 was set. In 2008, a new rule was established that again raised the threshold value to $45. This second rule was suspended in the following year to allow the additional funds to be used for a comprehensive stimulus package during the financial crisis. The third rule ($91, introduced in 2012) already became obsolete shortly after its introduction, when the oil price fell by half in 2014.30

As of early 2018, Russia has a new fiscal rule in place, again with a low oil price of just $40 as its threshold value. Budget plans for the years 2018 to 2020 are based on annual oil and gas revenues of only around 5 percent of GDP. The oil price in fact rose to over $60 at the end of 2017 and to around $70 in 2018, so revenues should be higher than estimated. Whether or not the Russian government will exercise the necessary fiscal discipline remains questionable in view of the short lifespan of past fiscal rules.

Fiscal Rules

Volatile oil price putting a strain on budget discipline

Volatile oil price putting a strain on budget discipline

Fiscal rules are legal provisions that are designed to ensure the long-term sustainability of budget policy. A fiscal rule is also enshrined in the German constitution in the form of the “debt brake”, (Basic Law, Art. 109 and 115), which limits new structural debt to 0.35 percent of GDP.a

When a country exports a large amount of its (finite) resources, a fiscal rule can be used to establish that only a portion of the revenues will be used and the rest will be saved. This ensures that future generations will also profit from the country’s resource wealth and isolates the government budget to some extent from major commodity price fluctuations. Fiscal rules can help to reduce negative effects of commodity exports on other economic sectors, known in economic jargon as the “Dutch disease”.

Government reserves are generally invested in low-risk foreign securities such as US or European government bonds. This prevents currency appreciation in boom periods and protects reserves from depreciation in times of crisis. If the fiscal rule is followed closely, pro-cyclical fiscal policy – that is, a fiscal policy that intensifies cyclical economic effects – becomes less likely, and the financial and political risks of fluctuating commodity prices sink. Comparative studies show, however, that fiscal rules are only effective in the long term under specific institutional conditions.b In Norway, for instance, an independent parliament, independent courts of law, and political competition would make it very difficult for the government to weaken its fiscal rule. In Russia, in contrast, there is no entity that could protect the fiscal rule from a change of priorities in the Kremlin.

a Christian Kastrop, Gisela Meister-Scheufelen, Margaretha Sudhof and Werner Ebert, “Konzept und Herausforderungen der Schuldenbremse” [Concept and challenges of the debt brake], Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 62, no. 13 (2012), http:// www.bpb.de/apuz/126016/konzept-und-herausforderungen-der-schuldenbremse?p=all (accessed 9 March 2018).

b IMF, The Commodities Roller Coaster. A Fiscal Framework for Uncertain Times (Washington, D.C., October 2015), 8, http:// www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Commodities-Roller-Coaster (accessed 11 August 2017).

Figure 5  The Finance Ministry’s fiscal rule, oil price, and reserves

The Finance Ministry’s fiscal rule, oil price, and reserves

Obstacles in Budget Policy

Budget imbalances in recent years have significantly increased pressure on the Russian government for reforms. A second or third “2016” with oil prices around $40 could make it necessary to implement austerity measures, which would further threaten the regime’s popularity.

Until recently, the Russian Finance Ministry has had few policy options to substantially increase revenues. At the end of 2014, President Putin announced a moratorium on tax increases that would apply up to the 2018 presidential election.31 The Finance Ministry nevertheless attempted to boost federal revenues through a variety of smaller adjustments. For instance, the government sold its shares in oil producers Rosneft and Bashneft. Capital accumulation, one of the pillars of the Russian pension system, was suspended in favor of a pay-as-you-go system so that all contributions could go toward ongoing pension payments. In the case of the corporate income tax, the possibilities for companies to carry forward losses have been limited.32 At the same time, a portion of the revenues from the corporate income tax has been shifted from the regional to the federal budget.33 Production taxes for the oil industry were increased, while the planned reduction of export tariffs was postponed.34 To balance the effects of the increased oil production tax on the Russian fuel market, a reduction of the gasoline tax was planned,35 but instead, the gasoline tax was significantly increased as well,36 and like with the corporate income tax, revenues were redistributed from regional budgets to the federal budget.37 The attempt to increase dividends from state-controlled joint stock companies partially failed, however, due to these companies’ resistance.38

The Finance Ministry attempted to increase federal revenues through a series of smaller adjustments.

Part of the losses in oil revenues were absorbed in this way, but the majority of measures implemented are not sufficient to increase tax revenues on a long-term basis. Either they could only be implemented once (privatization) or they increased current tax revenues at the expense of future budget years (pensions, corporate income taxes). The redistribution of regional revenues will not ease the federal budget in the long term because Moscow will ultimately have to take the responsibility for regional debt.

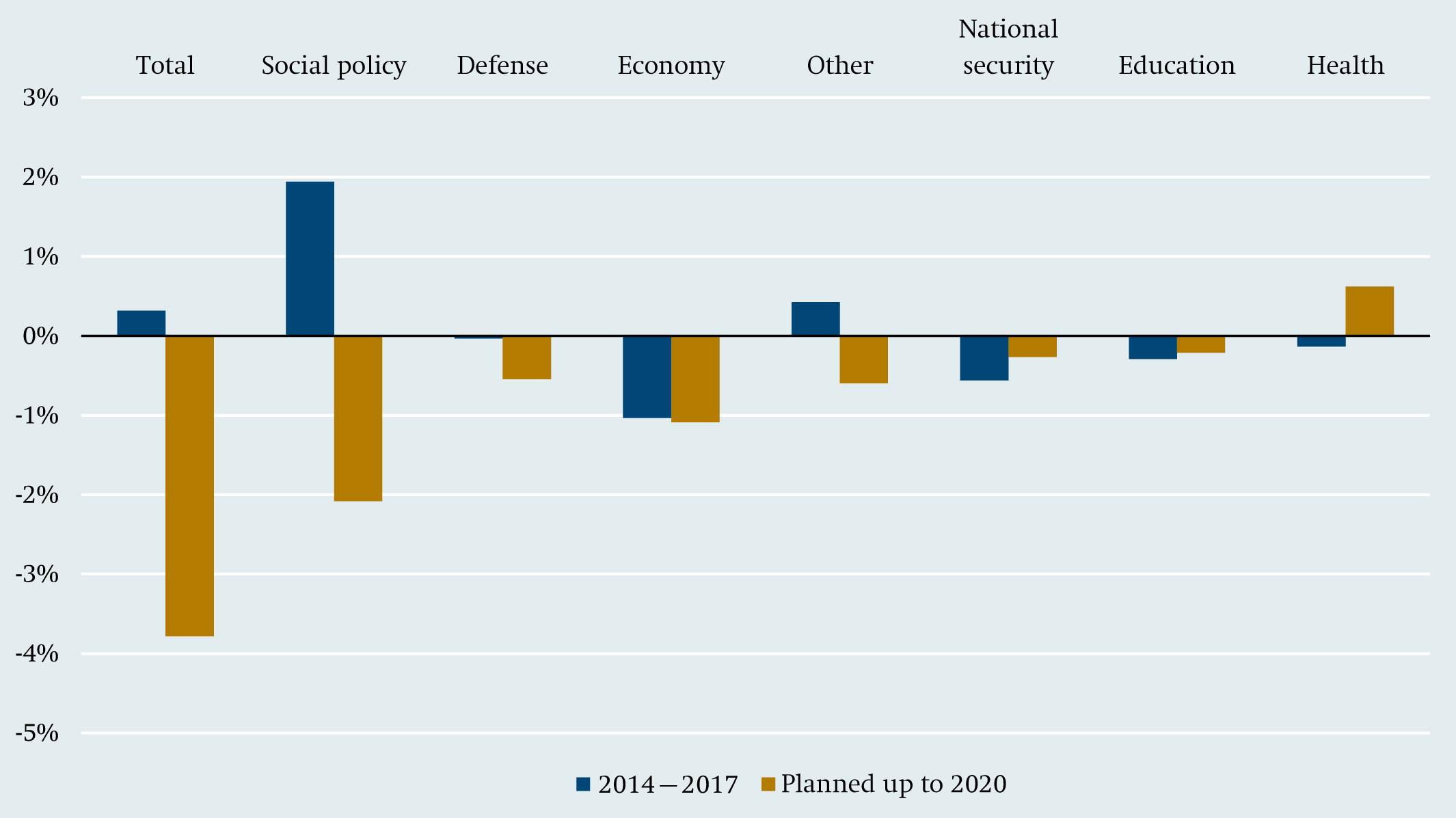

Before the tax and retirement age adjustment announced in 2018, the biggest adjustments were planned on the expenditure side. General govern ment spending in 2017, 35.2 percent of GDP, was unaffected by the fall in the oil price to 2014 levels (34.9 percent). The federal portion thereof fell slightly from 18.7 percent to 17.8 percent. Significantly more radical steps are planned for the years to come: the budget adopted at the end of 2017 for the period 2018–2020 envisions a reduction in federal spending to 15.6 percent of GDP.

ment spending in 2017, 35.2 percent of GDP, was unaffected by the fall in the oil price to 2014 levels (34.9 percent). The federal portion thereof fell slightly from 18.7 percent to 17.8 percent. Significantly more radical steps are planned for the years to come: the budget adopted at the end of 2017 for the period 2018–2020 envisions a reduction in federal spending to 15.6 percent of GDP.

|

Figure 6 Past and planned changes in spending (in percent of GDP) as of May 2018 |

|

Source: Calculations by author based on Minfin Rossii, Finansovo-ėkonomicheskie pokazateli Rossijskoj Federacii [Financial and economic indicators of the Russian Federation], https://www.minfin.ru/ru/statistics/ |

Social and pension policy is becoming more expensive

Social and pension policy is becoming more expensive

According to the 2018–2020 budget plan, the largest budget cuts relative to 2017 measured in percentage of GDP will be in the area of social policy. Including regional budgets and extrabudgetary funds, a decline of 2.1 percent of GDP is planned up to 2020, including a 1.0 percent of GDP cut in the federal budget’s social spending.

The social policy component of the budget is comprised largely of social benefits received by the population in the form of monetary transfers. The bulk of these (around 80 percent) consists of pension

Obstacles in Budget Policy payments. This budget item does not provide a complete picture of all of the Russian government’s social policy activities, however. Some measures that are designed to protect socially or economically disadvantaged segments of the population are financed through other budget categories such as health and education.

payments. This budget item does not provide a complete picture of all of the Russian government’s social policy activities, however. Some measures that are designed to protect socially or economically disadvantaged segments of the population are financed through other budget categories such as health and education.

|

Figure 7 Russia’s population below the poverty line, 2005–2016 (in millions of people) |

|

Source: Rosstat, Neravenstvo i bednost’ [inequality and poverty], http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/ statistics/population/poverty/# (accessed 2 February 2018). |

Obstacles in Budget Policy

The informal sector impedes targeted redistribution

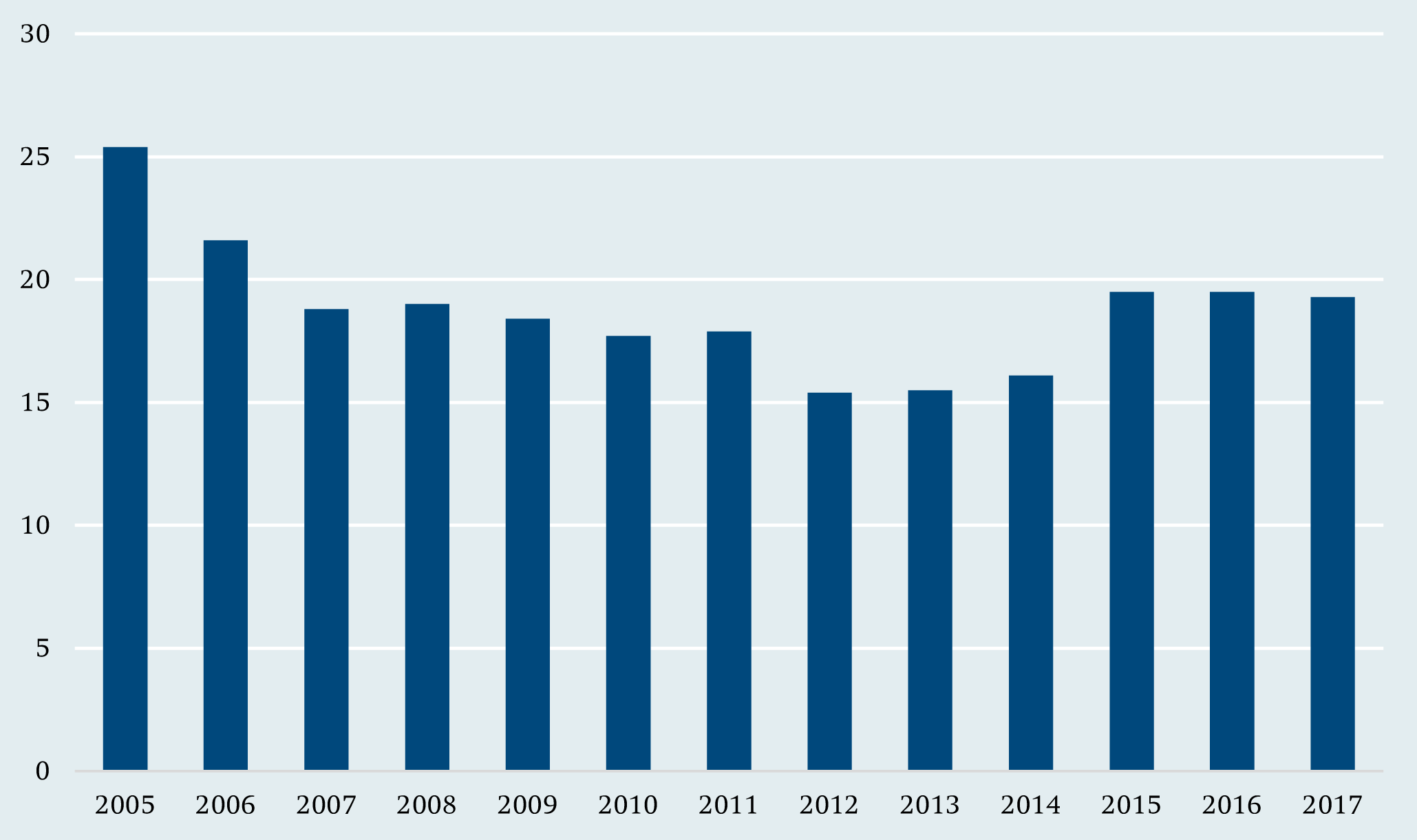

In Russia, over 80 percent of fiscal redistribution of income is achieved through pensions. This helps to attenuate the inequality in market incomes, which is extremely high by international comparison.41 Nevertheless, 20 million Russians live in poverty according to official Russian statistics. Economic growth in the 2000s and rapidly rising pensions in the period that followed caused the poverty rate to decline. Starting in 2014 with the economic crisis, poverty increased again. Pension levels are low by international comparison, at just 36 percent of average income. The majority of social transfers in Russia also do not go to the poorest sectors of the population but are distributed in a relatively indiscriminate way across income groups. This can be seen, for instance, in the basic pension: As a component of monthly pension payments, the basic pension is intended to guarantee a minimum level of social security. Pension rates are therefore differentiated into various categories of pension recipients or degrees of need. An evaluation of population census data from 2012 showed how badly this system is working: Only 20 percent of basic pensions paid ended up with the 20 percent poorest pension recipients.42 The unsystematic distribution of these funds means that the Russian government has to pay more than other countries for social policy in order to achieve a comparable reduction in inequality.

An important reason for the relative lack of focus in social benefits is that the informal sector makes up a large percentage of the Russian economy. In 2015, informal income made up 26.2 percent of total private household income. According to official data, around 21.2 percent of all workers were employed informally in 2016.43 Informal employment and the widespread employer practice of paying part of workers’ salaries in cash without withholding taxes (“in the envelope”) makes it more difficult for Russian authorities to clearly identify the actual level of benefit recipients’ need. This in turn makes it very hard to provide social support to meet existing needs in a targeted way. Thus, pension recipients in informal employment receive their full government pension even though they are only eligible to receive a percentage thereof. Furthermore, workers in informal employment do not pay contributions into the social funds. Measures designed to ensure that transfers are better targeted to existing needs could have a counterproductive effect, however: if government benefits were made to depend more heavily on formal wages and salaries, there would be the risk of more pension recipients attempting to engage in undeclared work, which would mean further growth in the informal sector.44

Pensioners benefit from redistribution

Overall, despite low pensions, pensioners in Russia are a net beneficiary of government redistribution. The legally guaranteed minimum pension is oriented toward a subsistence level of income calculated specifically for pensioners (as of 2017: 8500 rubles per month, or €129), which is slightly below the general poverty threshold (10,300 rubles per month, or €157). The proportion of pensioners living in poverty is, at 12.2 percent, below their proportion in the total population (21.6 percent). The losers in this “horizontal” redistribution across different demographic groups are families and adults living alone, who make up an overproportional percentage of the poor population. Redistribution from rich to poor (“vertical redistribution”) scarcely takes place at all through the Russian government’s tax and social policy.

The World Bank suspects that political considerations could be behind the privileged position accorded to pensioners, who play an important role as active voters and supporters of the Russian regime.45 Surveys confirm the importance of this group: not only is support for Vladimir Putin highest in the 60+ age group (88.8 percent of the vote); in the 2018 presidential election, expected voter participation in the 60+ age group was significantly above that in the young adult age group (18–24 years), at 86 percent and 47 percent, respectively.46 Opposition leader Alexei Navalny, in contrast, is regarded with skepticism by the older generation. In the Moscow’s 2013 mayoral election, where Navalny ran against Kremlin-backed candidate Sergei Sobyanin, the 60+ age group voted 70 percent for Sobyanin and just 14 percent for Navalny. In the 18–24 age group, Navalny beat Sobyanin with 53 to 35 percent of the vote.47

The pension system is becoming more expensive for Russia every year, as the percentage of the population that is dependent on government transfers grows. The proportion of pension recipients to employed people is shifting in Russia (as in many European countries), meaning that the pension fund depends on increasing transfers from the federal budget. A series of historically induced “demographic dips” in Russia have made this shift especially severe: Rosstat, the Russian statistical agency, predicts that the working-age population will shrink by 5 percent between 2018 and 2024, while the number of retired people will increase by 9.3 percent in the same period. This will require substantial transfers from the federal budget to the pension funds: In 2016, contributions to the pension funds amounted to 4.8 percent of Russian GDP, while pension payments were at 7 percent of GDP. The funding gap, which made up 2.2 percent of GDP in 2016, could rise to 3.3 percent of GDP by 2024 due to the country’s changing demographics.48 An increase in the retirement age in Russia – which is currently 55 for women and 60 for men – has been called for repeatedly by the Finance Ministry and economists, but was not implemented for many years due to explicit opposition from the Russian president.49 Only in June 2018, after the presidential election, did Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev announce that the government would raise the retirement age and the value-added tax in 2019, causing Putin’s popularity ratings to plummet.50

Return to paternalism

The Kremlin’s resistance to pension system reforms can be explained by the uniquely important role social policy plays in providing legitimacy to the Russian regime. While Putin pursued unpopular reforms inspired by economic liberalism in his first term of office, he embarked on a significant change of course in 2005. As a result, Russia again became a more paternalistic welfare state with a number of Soviet elements.51

This change is considered to have been triggered by the wave of protests that engulfed all of Russia in the summer of 2004. The demonstrations were against what is known as the “monetization of privilege” (monetisaziya lgot). The government wanted to eliminate special benefits for specific population groups like retirees and veterans (free use of public transport, free medications, health resort stays, etc.) and replace them with means-tested financial benefits. The protests soon led to the formulation of new political demands and focused increasingly on President Putin himself.52 The trust rating in the Russian president, a polling statistic compiled by the Levada Center, an independent public opinion research institute, reached a new low in 2005 at 38 percent.53 The demonstrations showed the extremely high willingness of pension recipients to mobilize politically.

As oil prices rose, the pension system increasingly became an instrument for the redistribution of windfall tax revenues.

The Kremlin reacted quickly: In Putin’s April 2005 speech before the Russian Federal Assembly, he declared social policy to be the most important task facing all levels of government. The government drafted a series of development programs with a significantly different focus from previous liberal-oriented reform plans. New transfers and benefits were introduced without the requirement of thorough means-testing. The “maternity capital” incentive – a one-time payment of the equivalent of €17,000 (purchasing power parity in the year the incentive was introduced) to mothers on their child’s third birthday – became the government’s showpiece, symbolizing the new direction of its social policies.

A media campaign flanked the return to a more paternalistic social policy. According to an analysis published in the state newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta on how social problems are reported on in Russia, media coverage starting in 2005 was aimed at presenting the government as the vanquisher of social problems. During the presidential election years 2008 and 2012 in particular, praise far outweighed critique of the government’s social policies in media reports on poverty, inequality, and discrimination.54

Russia’s expansive spending policy continued even after Putin moved to the position of Prime Minister in 2008. Against the backdrop of rising oil prices, the pension system increasingly became a rentier-state type instrument for the redistribution of windfall tax revenues.55 Inflation-adjusted pension payments increased 76 percent in the period 2007–2010 through annual pension increases and a revaluation of previous years of work. This was intended mainly to shield the population from the impacts of the 2009 economic crisis. Yet in 2010, when the economy was growing again at a rate of 4.5 percent, pension payments increased further. Public transfers played an increasingly important role in the continuous increase in Russians’ incomes, while private-sector wages made only a minor contribution to economic growth, especially after 2010.56

Pensions increase oil dependence

The large volume of pension payments and social benefits posed a particular risk to Russian budget stability: One the one hand, falling oil prices reduced government revenues, which are needed to finance transfers. An added challenge was that spending on social policy increased during the oil price slump. Since the dropping oil price meant that the ruble declined in value as well, imported consumer goods in Russia became more expensive, and consumer goods prices rose overall.57 Pension and social benefit recipients in Russia are legally guaranteed adjustment of their benefits for inflation. Due to this “scissors effect”, with revenues and expenditures moving in opposite direction, social policy spending exacerbates the Russian budget’s dependence on oil.

When federal tax revenues fell nominally by 6 percent, pensions had to be increased nominally by 11.4 percent at the same time to compensate for the previous year’s inflation (additional spending amounting to 1 percent of GDP). In 2016 as well, tax revenues fell nominally, while pensioners were due another inflation adjustment of 12.9 percent. With its reserves dwindling rapidly, the Finance Ministry pressed for an exemption to this rule. The Kremlin stalled on passing the resolution: first, the 2016 inflation adjustment was split into two parts, with a first increase of 4 percent in early 2016 and a second announced for the fall. This second increase did not take place, however: It was replaced by a one-time payment of 5,000 rubles (€76) to all pensioners – a symbolic amount considering the level of inflation adjustment.58

Compared to its decisions on other categories of budget spending, the Russian leadership acted very cautiously in deciding on pension inflation adjustments. While it significantly reduced spending on education and health without any major discussion in 2015 and 2016, it only intervened into pension system expenditures when the Finance Ministry’s reserves were close to being exhausted. The matter was also decided only after an explicit vote by the president.59

Regression instead of reform

While the government kept rising social policy expenditures in check by not following through with inflation adjustments, it was still not addressing fundamental problems such as the lack of focus in benefit provision and the looming risks of demographic change.

One possible way to resolve the “informal sector dilemma” in the pension system would be an approach in which individuals receive a portion of their pensions through a funded pension system. Employees who report their income officially and whose employers make payroll social security contributions could then be rewarded accordingly. If contributors have trust in the pension system, a similar effect could be achieved through a pay-as-you-go scheme. Trust is very low in Russia, however, and has declined further due to the incomplete inflation adjustment of 2016 and the “freezing” of the previously existing funded pension scheme.

A funded pillar was first introduced into the Russian pension system as part of the liberal reforms of 2002. Of the individual’s pension contribution, which is currently 22 percent of gross wages, 6 percent was set aside in the name of the contributor for future pension benefits. In 2014, however, this fund was frozen, which means that the contributions are not continuing to accumulate but are being diverted to cover ongoing pension payments. This helped to reduce transfers from the federal budget into the pension system. The savings are estimated at 342 billion rubles (€5.2 billion) for 2016 auf, 412 billion rubles (€6.3 billion) for 2017, and 471 billion rubles (€7.1 billion) for 2018 (0.4–0.5 percent of GDP).60 The decision to freeze accumulated individual pension savings has been extended multiple times already. There is currently no indication that the funded pillar will be reactivated, even in the draft budgets for the years up to 2020.61 A return to a system in which pensioners are required to build up their own individual pension reserves is thus not likely.

The burdens to the pension system are being hidden and shifted into the future. Although the budget deficit is declining, “implicit debt” is increasing.

From the viewpoint of fiscal sustainability and transparency, the decision to freeze the funded pillar of the pension system was a step backwards. Not only does it render the burdens to the pension system invisible and shift them into the future; it means that even as the budget deficit is shrinking, “implicit debt” is on the rise. Government-guaranteed future pension payments that are not covered by reserves or future tax revenues create hidden government liabilities. Pension transfers that are saved today will have to be paid off out of the budget in the future.62

No simple solutions

In the context of the economic crisis and declining tax revenues, the Russian leadership has had few simple options for action in the field of social policy. The Kremlin had to choose between unpopular reforms and budget cuts that would jeopardize political support from important voter groups, and a more debt-financed social policy that would increase medium- to long-term budget risks. The middle course it decided to take is beset by both political and fiscal risks, but most likely poses no immediate danger to political stability.

The political costs of this strategy are difficult to estimate, either from an outside perspective or by the Kremlin itself, since there are few forums for the public expression of dissatisfaction in Russia, and credible political alternatives are quashed before they can take root. Opinion surveys show, however, that public support for government social policy had been declining even before the controversial pension reform of 2018. The social policy index of the state survey research institute WCIOM, which has been collecting data on the subject since 2007, reached a new low in mid-2017. In 2015, 38 percent of the population reported being satisfied with social policy while 27 percent reported being dissatisfied. In mid-2017, this distribution tipped in the opposite direction: just 25 percent reported being satisfied, while 43 percent were dissatisfied.63 Studies by the Russian Academy of Sciences also show that the percentage of Russians who generally favor change increased dramatically in 2017 to over half of all respondents. The desire for change was less focused on political change, however. Sociologists reported a growing desire for a paternalist government that would play a stronger role in addressing the population’s social problems.64

Procrastination on unpopular reforms and the increase in implicit debt that is not covered in the budget figures create new fiscal risks. The population’s trust in the pension system – a key precondition for future reforms – has suffered from the government’s efforts at short-term budget savings.

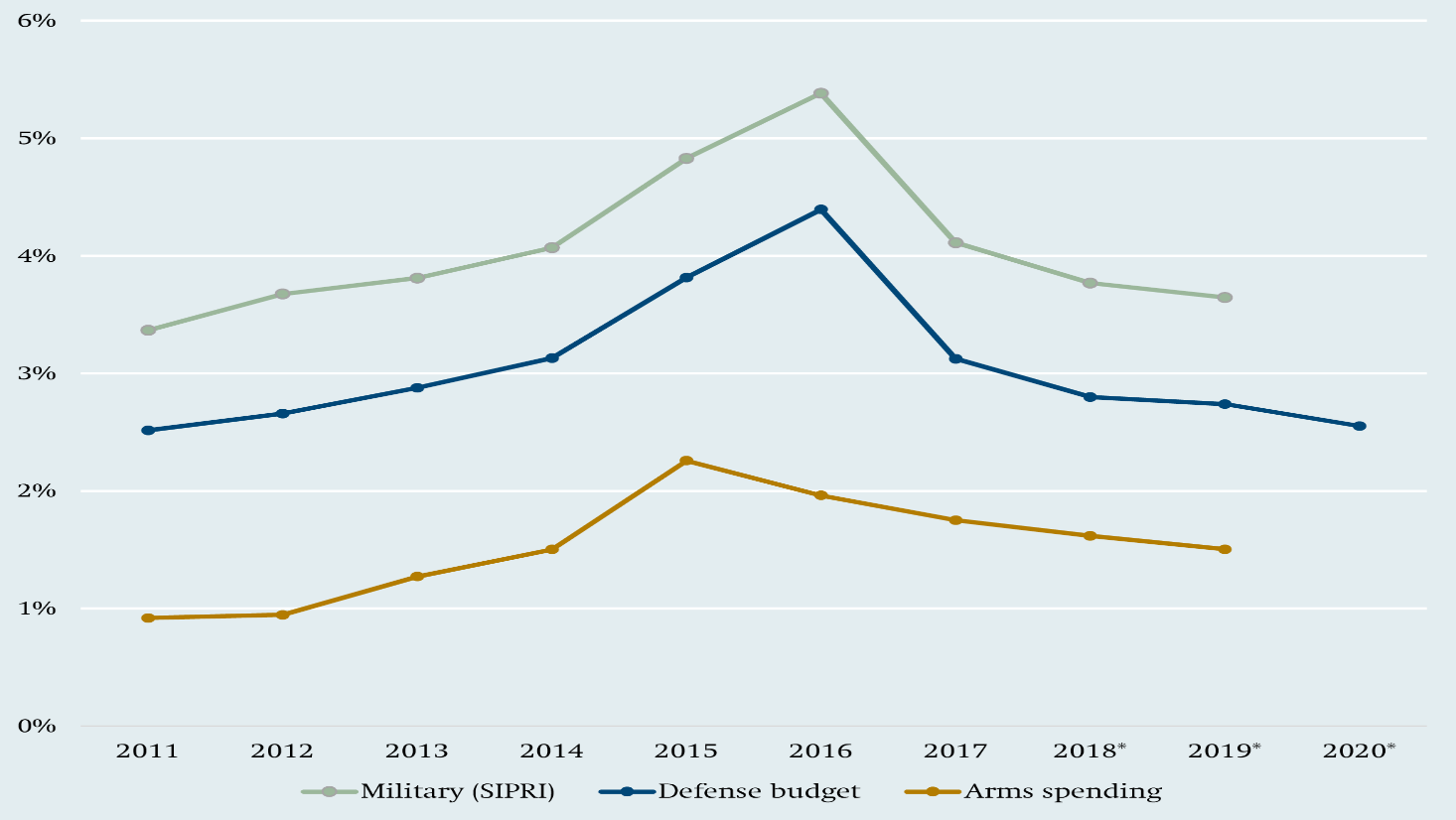

Defense expenditures are top priority

The 2017 defense budget was 3.1 percent of GDP (€43.3 billion). Defense expenditures, which are paid almost completely out of the federal budget, varied widely in recent years, reaching a new peak at 4.4 percent of GDP in 2016. In 2011, the defense budget was just 2.5 percent of GDP. The budgets project that defense expenditures up to 2020 will decline to 2.6 percent of GDP.

Russia is spending more on the military than its defense budget would suggest, however. Just three quarters of Russian military expenditures, classified according to the definition of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI),65 actually come out of the defense budget. The rest, amounting to another 1 percent of GDP (€13.8 billion) in 2017, are paid for out of other budget categories such as social policy (military pensions), education, and health.

Since 2008, the Kremlin has been pursuing a large-scale reform and upgrade of the Russian armed forces with the aim of returning Russia to its former status as a military superpower.66 The turning point in Russian arms policy came with the Georgian War of 2008, when the weaknesses of the Russian army became clearly apparent.67 Part of the increase in spending went for the organizational restructuring of the military: wages in the Russian armed forces were increased significantly in 2012 to attract qualified staff for a

Obstacles in Budget Policy professional army.68 But armaments account for most of the increase in military spending.

professional army.68 But armaments account for most of the increase in military spending.

|

Figure 8 Defense budget, military spending, and arms (in percent of GDP) as of May 2018 |

|

* Figures from the 2018–2020 budgets were used. Sources: Defense budget: Minfin Rossii, Finansovo-ėkonomicheskie pokazateli Rossijskoj Federacii [Financial and economic indicators of the Russian Federation], https://www.minfin.ru/ru/statistics/; Military and arms spending: Julian Cooper, Prospects for Military Spending in Russia in 2017 and Beyond (Birmingham, 2017), https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/government-society/crees/working-papers/prospects-for-military-spending-in-Russia-in-2017-and-beyond.pdf (accessed 2 October 2017). |

Armament spending is planned as part of the long-term programs known as Gosprogramma vooruzheniy (GPV, “state armament program”), which have a time horizon of ten years and are generally updated at five-year intervals. The GPV-2020 program adopted in 2010 included a drastic increase in arms expenditure for the decade from 2011 to 2020. Over that time period, 19 trillion rubles were to be allocated to weapons purchases (€472 billion at the exchange rate in 2010 when the program was adopted or 41 percent of Russian GDP in 2010).69 The stated primary goal of the program was to increase the percentage of modern weapons in the Russian military arsenal to 70 percent by 2020. In September 2017, President Vladimir Putin announced that 58.3 percent of Russian military weapons had already been modernized in the previous year.70 There is no clear definition of what qualifies weapons systems as “modern” or which specific weapons stock the figures refer to, but supplier figures on newly produced weapons show significant progress in production.71

The process of planning the follow-up program (GPV-2025) indicates that the tense budget situation has at least temporarily dampened the Kremlin’s arms ambitions. The new strategy for the years 2018–2027 includes spending in the amount of 19 trillion rubles (€288 billion). In nominal terms, it is similar in volume to the predecessor program, GPV-2020. As a percentage of GDP, the scope of the new arms program is just half of that (20.6 percent of GDP in the year of the program’s adoption, 2017).

|

Direct Spending on Military Operations in Ukraine and Syria According to estimates, the direct costs of Russian military operations in Syria and Ukraine make up just a few percent of the Russian defense budget, which amounted to around €43.3 billion in 2017. The necessary expenditures could thus be covered entirely through reallocations, for instance from the budget for military exercises, without any added burden on the budget. As the government provides almost no official figures, and most of the data on military exercises are classified as secret, the available sources consist either of information compiled by journalists or independent studies – for instance, those released by the opposition party Yabloko. In the case of Syria, the fact base is slightly better due the somewhat lower level of secrecy. In March 2016, President Putin stated that the first six months of the Syrian operation cost 33 billion rubles (€500 million). Russian experts estimate the costs of the operation from October 2015 to September 2017 at between 188.6 and 194.3 billion rubles (€2.9–3 billion).a The costs of the military operation in Donbas (independent of the annexation of Crimea) are estimated at 53 billion rubles (€800 million) for the first ten months (March to December 2014).b Russian economist Sergey Aleksashenko assumes $2 billion for the year 2015. That just covers the direct costs of pay and provisions for the deployed soldiers, but not the provisions for refugees or economic assistance to the self-proclaimed “people’s republics” in Donbas.c a Yabloko, Rossija potratila na Siriju ot 188.6 do 194.3 mlrd rublej [Russia spent 188.6 to 194.3 billion rubles on Syria], 2017, http://www.yabloko.ru/news/2017/09/22 (accessed 8 June 2018). b Ilya Yashin and Olga Shorina (eds.), Putin.War. Based on Materials from Boris Nemtsov (Moscow, May 2015), http:// 4freerussia.org/putin.war/Putin.War-Eng.pdf (accessed 3 October 2017). c Reva Bhalla, “The Logic and Risks Behind Russia’s Statelet Sponsorship”, Stratfor, September 2015, https://www.stratfor. com/weekly/logic-and-risks-behind-russias-statelet-sponsor ship (accessed 24 June 2017). |

The resolution on the new arms program was also postponed repeatedly. A decision on the GPV-2025 should have been made in 2015. In the light of the falling oil price and economic sanctions, this was put off again and again, as the Finance Ministry and the Defense Ministry had very different ideas about the scope of the budget, and the President chose not to exercise his authority to end the debate. In 2014, Putin had made relatively vague indications as to the overall direction it should take: he said the program should be realistic and within the government’s financial means.72

The defense budget grew to a record high in 2016 with no direct connection to the preceding escalation of foreign policy crises in Ukraine and Syria.

In contrast to the long-term armament programs, the change in defense spending from year to year does not necessarily indicate a change in the Kremlin’s priorities. From the outset, the GPV-2020 envisioned a more dramatic increase in arms spending in the second half of the program period.73 The partially inconsistent trajectory of spending from 2011 on was also due to the mode of financing military spending: armaments industries had received government guarantees for loans in the amount of around 1.2 trillion rubles (€18 billion) to start fulfilling arms contracts immediately.74 These guarantees are not contained in the defense expenditures in the early years. Starting in 2016, the Finance Ministry ended the practice of using bank loans to provide co-financing, and paid off the majority of the loans (793 billion rubles, or €12 billion). A further repayment took place in 2017 (approx. 200 billion rubles, or €3 billion). These payments caused the defense budget to reach a record high for a period of 2016, with no direct connection to the preceding escalation of foreign policy crises in the Ukraine conflict and in Syria.

Coalition for arms

The Kremlin’s security policy priorities only partially explain the increase in spending on long-term Russian arms programs. The systematic implementation of the wide-ranging GPV-2020 is also rooted in a particular constellation of domestic and industrial policy factors.

The most important decisions on the state defense orders are made by the military-industrial commission, whose individual members have a military or secret service background. Significant overlapping of responsibilities makes it easier for the military to assert its particular interests in the planning of expenditures: the defense ministry not only acts as arms buyer but is also responsible for evaluating the urgency of certain purchases and for planning supply needs. There are also major overlaps in staffing between the management of arms manufacturers, the presidential administration, the security agencies, and the military.75 The political weight of influential military-industrial interest groups has increased further with the expansion of defense spending. Furthermore, the Minister of Defense since 2012, Sergei Shoigu, is among the most popular politicians in Russia and has the strongest individual political profile of all of the ministers.76

In the public discourse, the drastic increase in arms spending has often been justified with industrial policy arguments. Vladimir Putin likes to present the defense industry as an engine of growth for the Russian economy, although economists cast doubt on the industry’s ability to play this role. In many cities, however, arms manufacturers are among the most important and in some cases the only major employers. As a result, they play a highly significant socio-economic role.

The risks for the arms industry

Against this backdrop, it is unsurprising that the arms sector has become one of the most important political clienteles for the Russian leadership: the arms industry employs around two million workers, whose support for the Kremlin regime is at times even instrumentalized in the state media. A prime example of this role can be seen in a television appearance by workers for the company Uralvagonzavod, which among other things is building the platform for the new combat tank Armata. During Putin’s annual live television conference, in which he takes call-in questions, they offered to come to Moscow and help clear the streets of the demonstrators who were protesting against electoral fraud in Winter of 2011/2012.77

According to the data from the Ministry of Industry, arms industry production more than doubled between 2010 and 2016.78 The share of civilian production in the arms industry fell during the period from 33 percent (2011) to 16 percent (2015).79 The companies are largely oriented toward the Russian defense ministry as their main buyer.

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

17.4 |

5.8 |

6.4 |

13.5 |

15.5 |

12.9 |

10.1 |

Due to their dependence on Russian state contracts, managers and workers at the arms producers are uneasy that budget plans project a significant decline in military spending.80 President Putin and then Vice President Dmitri Rogozin, who was until recently responsible for the arms industry (replaced by Yuri Borisov in May 2018), see the future of the industry in the production of goods with civilian applications and want the companies to open up new export markets.81

The Russian defense industry is being squeezed by high-tech western companies on the one side and cheaper Chinese manufacturers on the other.

The Russian defense industry has been successful in selling its goods abroad in recent years, with exports of around $15 billion annually. But it is being squeezed by high-tech western companies on the one side and cheaper Chinese manufacturers on the other. For many years, China was one of the most important buyers of Russian weapons, but it has made great progress in its own weapons manufacturing – in part through licensed production of Russian weapons systems. In recent times, Chinese providers have been penetrating markets such as Nigeria and Venezuela that were traditionally dominated by Russian arms suppliers. Given that Chinese arms producers possess the backing of a much more financially powerful state, as well as superiority in many production processes, Russian producers will have a difficult time asserting themselves against Chinese competitors in the future.82 With some weapons systems such as the air defense system S-400 or the fighter jet Su‑35, the Russian industry still holds the technological lead. The combat tank Armata, which is one of few weapons systems developed after the end of the Cold War, has good chances of becoming internationally competitive as well – provided Russia decides to export it.83

Whether there will be a successful and significant shift to civilian production is questionable since the arms industry’s own technological developments are either useful only for weapons systems or are classified as secret.84 As a result, it is being discussed whether the arms industry should be given preferential treatment in tenders by other state corporations as a kind of “start-up aid” for the sale of civilian goods.85

The sanctions imposed during the Ukraine crisis and under the US CAATS Act made it more difficult for the Russian defense industry to gain access to capital and to import goods that it needed for production.86 The loss of Ukrainian suppliers had already begun negatively impacting the sector in 2014. For Russian banks with international operations, the new sanctions substantially increased the risks of doing business with the arms industry.87 For this reason, Moscow created a special financial institution to support the defense industry on the foundations of Promsvyazbank, which the Russian central bank took over at the end of 2017 to prevent its collapse.88

No change of course up to now

It is unlikely that there will be a rapid change of course from the rearmament that has been pursued up to now. During the budget crisis of 2015 and 2016, the Russian leadership showed willingness to limit military spending. Yet even if the political will to do so could be maintained despite the recent rise in oil prices, the drastic cuts planned by the Finance Ministry would be difficult to implement for structural reasons. First of all, actors from the arms industry and military have a great deal of political weight in the decision-making process. In the last few years, for instance, they have repeatedly succeeded in having defense spending levels revised upward after budgets were passed. The growing foreign policy tensions between Russia and NATO are strengthening forces within the Kremlin that focus on security policy arguments. Second, due to sanctions, demographic developments, and increasing competition, the arms industry will have to battle increasing headwinds in the years to come. A significant decline in government arms contracts would have a severe impact on arms producers and could destabilize the socio-economic situation in a number of cities.

Ultimately, whether or not the planned budget reductions succeed will depend on arms producers’ flexibility – and this has been relatively low up to now. One can safely assume that the Kremlin will not allow these companies to fail, risking mass unemployment in many of Russia’s monotowns. A newly established bank serving the arms industry and possible cross-subsidies from other state corporations will continue even if arms spending falls. This will create new risks that could materialize in future budgets, for instance, if borrowers default on loans from Promsvyazbank.

Russian discourse: Concepts without consequences

The future of arms and social policy spending plays a central role in the Russian (expert) discourse on reform plans. On explicit instructions from the Kremlin, two reform proposals were developed starting in 2016: On the one hand, there is the proposal by a team at the Center for Strategic Research, headed by the economist and former Minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin. On the other hand, there is the “strategy of growth” developed by the Stolypin Club, now under the leadership of Russian businessman and Presidential Commissioner for Entrepreneurs’ Rights Boris Titov.89 Whereas Kudrin’s perspective on Russian economic policy is based more on neoclassical, supply-side economics, Titov’s strategy is clearly rooted in the Keynesian, demand-oriented tradition. Kudrin’s plans are much more strongly rooted in current economic literature. The two sides are in agreement on the urgent need for reform of the legal system as a precondition for better protection of property rights. On questions of budget policy, however, the two strategies take opposing positions.

Kudrin’s fiscal manoeuver

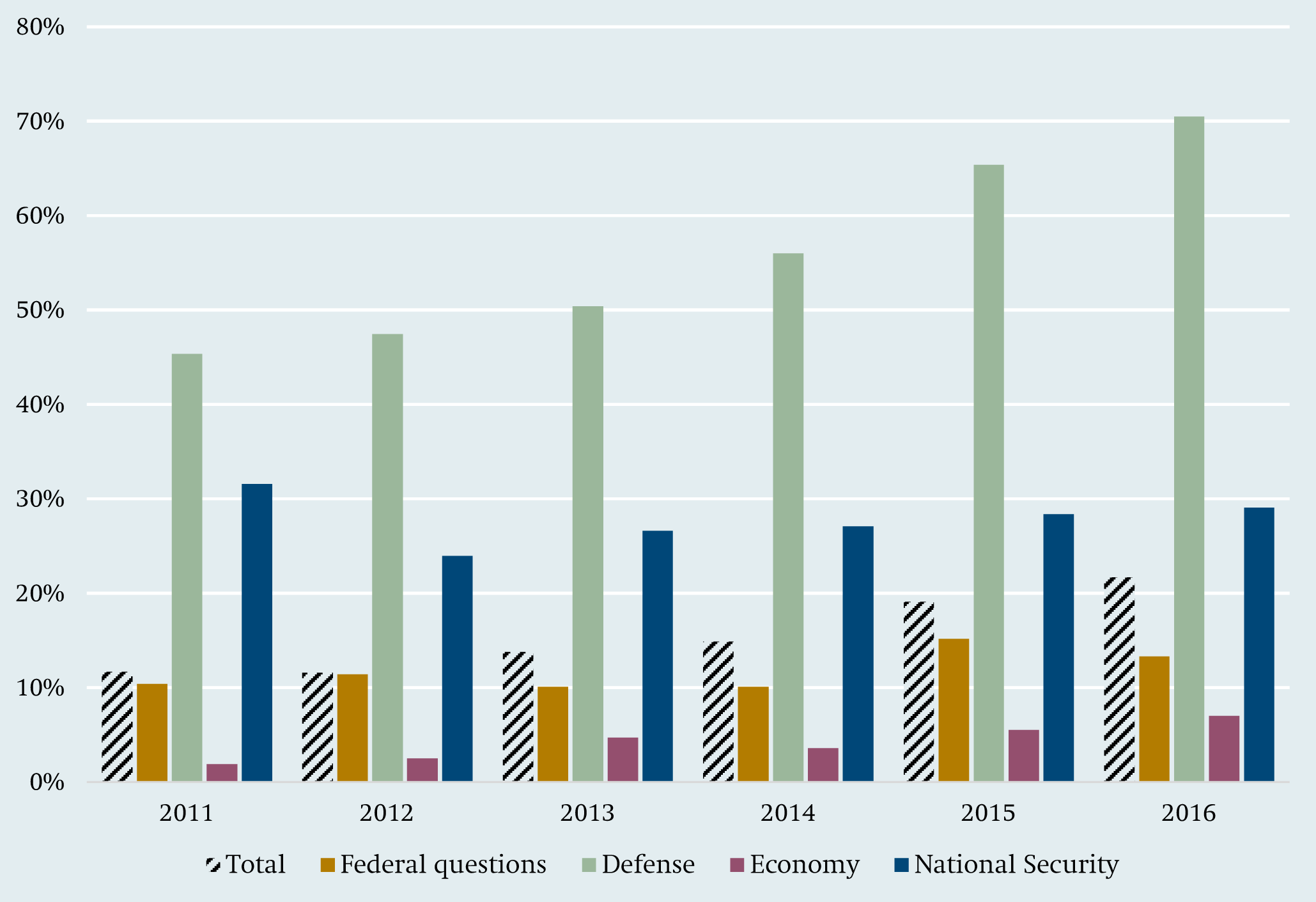

Kudrin proposes a redistribution of fiscal spending within the budget (“fiscal manoeuver”). He distinguishes between expenditures in productive areas (such as education, health, and infrastructure), which have a positive impact on economic growth, and expenditures in unproductive areas, which have little or even a negative impact on growth (military and security).90 In the category of expenditures with a negative impact, Kudrin includes social transfers that do not reach the needy population they are targeted at but are instead distributed indiscriminately (these are not taken into consideration in the following statistical analysis, however, due to the lack of data).

|

Budget category |

GDP |

Short-term growth |

Long-term growth |

|

Government spending (total) |

0.91 % |

||

|

Defense |

0.22 % |

–0.29 % |

–0.52 % |

|

National security |

0.78 % |

0.26 % |

–1.45 % |

|

Education |

0.38 % |

0.18 % |

0.47 % |

|

Health & sports |

1.25 % |

0.09 % |

0.14 % |

|

Infrastructure |

1.64 % |

0.26 % |

–0.68 %a |

a The long-term negative effect of infrastructural spending is explained by the fact that many projects are not geared toward economic needs. This is true, for instance, of the megaprojects carried out in recent years (Olympic Games, Soccer World Cup, and Kerch Bridge).

An empirical analysis by Alexei Kudrin and Alexander Knobel shows that expenditures on health and infrastructure in Russia lead to a disproportionate increase in GDP (1.25 percent and 1.64 percent, respectively, for every 1 percent of GDP increase in expenditures), while defense spending increases GDP little (0.22 percent, see Table 2). Defense expenditures are even detrimental to long-term growth, while educational spending in particular leads to positive growth effects.

Based on their analysis of these contributions to economic growth, a comparison with other countries, and the effectiveness of the various ministries, Kudrin and his colleagues recommend increasing spending on infrastructure, education, and health care, and decreasing spending on defense, security, and a number of subsidies. On the subject of social policy, Kudrin highlights the potential for savings in the area of untargeted social transfers.91 His proposals thus strongly resemble those of the World Bank for Russian budget policy.92

The Stolypin Club’s “strategy of growth”

The authors of the Stolypin Club’s alternative proposal call for a substantially more expansive monetary policy on the part of the central bank to promote private investment. At the same time, pointing to unused production capacities in Russia, they recommend boosting domestic demand through an increase in government spending to generate increased economic growth.93 Their plan aims to achieve long-term budget equilibrium not through spending cuts but through the increase in tax revenues resulting from economic growth. Titov pairs his Keynesian perspective with a developmental state approach: According to this idea, active industrial policy and ongoing import substitution will lead to the emergence of leading international enterprises in a variety of technological sectors. Titov and his colleagues expect that the defense industry will make a positive contribution to growth, and warn against a decrease in defense spending.94 Overall the Stolypin Club’s approach is less systematic in its design and more eclectic than Kudrin’s research-based recommendations.

Low likelihood of implementation

The Kremlin has shown no clear preference for either of the plans. After a presentation of the two reform papers, Putin suggested that a joint strategy be developed combining both concepts.95 In view of the contradictions between a number of the recommendations, this would be virtually impossible to carry out. Overall, the reaction on the part of the Russian leadership reveals a certain level of disinterest in the proposals for structural change.

Putin’s apparent reluctance to make a decision in this regard is most likely rooted in the fact that both programs contain ideas that contradict the Kremlin’s current political priorities. Kudrin calls for widespread cuts in areas affecting important political clientele groups that currently depend on the “unproductive expenditures” in the budget. Titov’s proposal may entail too many economic risks: Above all, the dangers of inflation but also of increased government debt make a more expansive monetary and fiscal policy uninteresting to the Kremlin, which has tended to act in a more conservative way up to now. This ambivalence became clearly apparent in Putin’s address to the Federal Assembly in March of 2018. The announcements in the first part of his address strongly recalled Kudrin’s demands: increasing spending on education, health, and infrastructure. The second part glorified the successes of Russia’s military buildup. There was no mention of any decrease in military spending.96

Contested Control over State Finances

Economic know-how and reform concepts can be found predominantly among the “liberals” within the Russian elite, who still hold important positions in the central bank, the Finance Ministry, and the government-owned Sberbank. In those contexts, however, they operate purely as technocrats and have only a limited scope of action. As political actors, the liberals are just as discredited in Russia as liberal political ideas themselves. This is due in part to the regime’s propaganda campaign dissociating it from the period of radical liberalization of the government and the economy in the 1990s. For the liberally inclined elite, the annexation of Crimea and the escalation of foreign policy confrontation with the West meant even further weakening of their position in the domestic political landscape.

Instruments of long-term voluntary commitment, such as budget plans and fiscal rules, require a minimum level of transparency and separation of powers to amount to more than just good intentions.

Sustainable fiscal policy in Russia is inhibited by problems of expenditure control. Instruments of long-term self-commitment such as budget plans and fiscal rules require a minimum level of transparency and separation of powers to amount to more than just good intentions. In reaction to the collapse of tax revenues, however, control over budget funds became more centralized and less transparent. Some of the revenues also do not make it into budgets but remain with state-owned enterprises. This increases their political clout, and since they are profiteers of the status quo, they have no interest in a reform of Russian economic policy.

Undermining the separation of powers

By granting the parliament budgetary powers, the Russian constitution gives the State Duma and the Federation Council an effective instrument for shaping public policy. In past years, however, Russia’s parliament has barely made use of this fundamental right in the sense set out in the constitution. After the acrimonious budget debates of the 1990s, which often ended in protracted impasses and delayed budget resolutions, there have been no further disputes between parliament and the executive since the early 2000s. In the Duma today, half as much time is spent discussing budget laws as in the early 2000s. The number of changes made during the readings in the Duma have declined continuously as well.97 As a result, budget planning has become very predictable.