The political geography of Kashmir has changed radically in recent months. The starting point was the Indian government’s decision on 5 August 2019 to divide the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) into two Union territories. In response, Islamabad published a map on 4 August 2020 showing all of Kashmir as part of Pakistan. At the end of September 2020, the Chinese government terminated the status quo with India in the Ladakh/Aksai Chin region. This indicates a new phase in the conflict over Kashmir, in which China and Pakistan could work more closely together. In addition, the conflict is being expanded to include a new geopolitical dimension because, for China, the dispute with India is now also part of the struggle with the United States over the future distribution of power in the Indo-Pacific.

The territorial affiliation of the former princely state of J&K has so far been the subject of two largely independent conflicts: (1) the well-known dispute between India and Pakistan; (2) the less well-known dispute between India and China over the demarcation of their approximately 3,500-kilometre-long border, which also affects Kashmir. Recent developments could lead to the two previously separate conflicts becoming more intertwined in the future.

The Indo-Pakistani Conflict over Kashmir

Following the independence of British India and the creation of India and Pakistan in August 1947, a number of princely states initially remained independent, including J&K. When tribal warriors from Pakistan invaded, with support from Pakistani officers, the Hindu Maharaja of J&K turned to the Indian government for military assistance. At the end of October 1947, the princely state joined the Indian Union, which, in return, sent troops to support the Maharaja. The fighting against the tribal warriors developed into the first Indo-Pakistani War, which ended in January 1949 with an armistice. Since then, the former princely state has been divided into two parts, one Indian and one Pakistani.

Kashmir has a high symbolic value for India and Pakistan in the context of their respective conceptions of the state. Pakistan, which was founded as a state for the Muslims of British India, claimed Kashmir – with its majority Muslim population – as one of its parts. For India, Kashmir became a symbol of the secularism and openness of the new state to all religious communities.

The ongoing Kashmir conflict between India and Pakistan can be divided into two major phases. The first phase, from 1947 to 1972, saw the internationalisation of the dispute. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru brought the conflict before the United Nations (UN) and proposed a referendum to decide whether the territory should belong to India or Pakistan. Since 1948, the UN Security Council has adopted a number of resolutions concerning the conflict. The tenor of these resolutions is that, firstly, all Pakistani troops must withdraw from J&K. Secondly, an interim administration, assisted by Indian troops, should be set up. Thirdly, this administration would have to prepare a referendum to be held across J&K. Kashmir’s independence was not provided for in the resolutions and is rejected by India and Pakistan. China did not become a member of the Security Council until 1971 and therefore did not participate in the UN resolutions.

In 1948, the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) was established to settle the conflict and monitor the ceasefire in force since 1949. In 1951, the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) took over this task. Until the 1960s, Security Council veto powers such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union made various unsuccessful attempts at mediation.

The second phase brought a bilateralisation of the conflict. It began with the Simla Agreement of 1972, which followed the third war between India and Pakistan in 1971, in which East Pakistan was split off and Bangladesh was founded. At that time, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi failed to take advantage of Pakistan’s military defeat and achieve a lasting solution to the Kashmir issue. Both states agreed in the Simla Agreement to deal bilaterally with outstanding issues and to establish a new Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir. India subsequently suspended its cooperation with UNMOGIP, which continues to monitor the ceasefire along the LoC.

Pakistan continued to try to internationalise the Kashmir issue, for example by provoking regional crises such as the Kargil War in 1999, by having the Pakistani army and intelligence agencies support terrorist groups that carried out attacks in the Indian part of Kashmir, and by denouncing the human rights violations of Indian security forces in Kashmir in international forums.

The international community gradually moved away from the UN resolutions. All Security Council veto powers repeatedly called for a bilateral solution to the conflict. In December 2003, Pakistan’s president, Pervez Musharraf, also distanced himself from the UN resolutions, paving the way for the so-called composite dialogue with India. In 2007, the two sides agreed on a compromise on the Kashmir issue that has never been made public, essentially enshrining the status quo. In 2008, the terrorist group Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT), supported by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), carried out an attack in Mumbai, which brought an end to the dialogue.

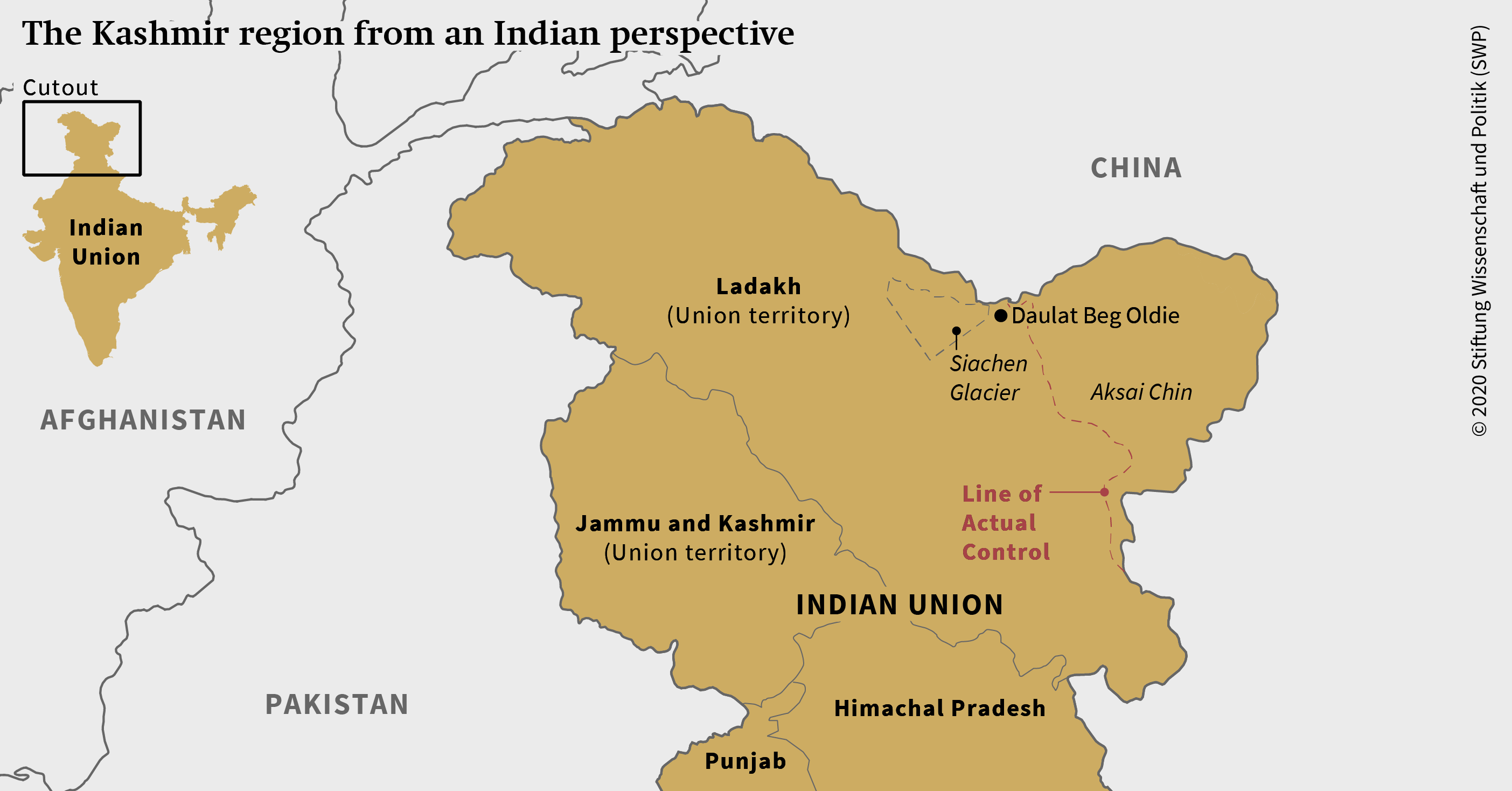

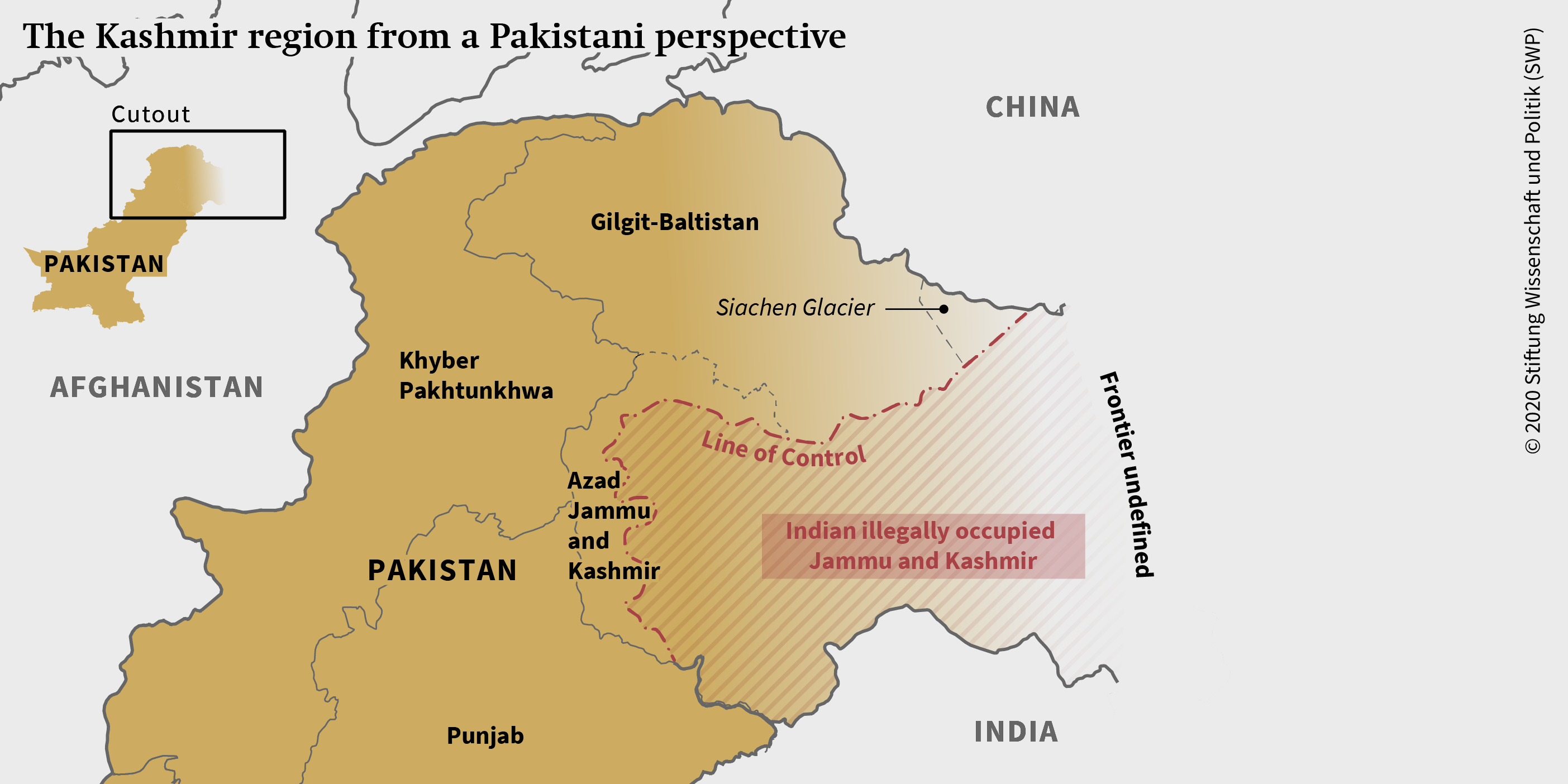

The different positions of India and Pakistan are also reflected in the official maps. Since India insists that the whole of Kashmir joined the Union in October 1947, Indian maps therefore show the whole territory of the former princely state as Indian territory. Because J&K has a border with Afghanistan in the north, India also sees itself as a direct neighbour of Afghanistan. Pakistan, on the other hand, saw the whole of J&K as a disputed territory – according to the terms of the UN resolutions – whose status would only be decided in a referendum. Therefore, Pakistani maps have not depicted Kashmir as part of its own territory, even though the regions Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) and the formally independent state of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) are de facto ruled by Islamabad.

The Indo-Chinese Conflict in Kashmir

From the international perspective, “Kashmir” is synonymous with the conflict between India and Pakistan. Since the late 1950s, however, the People’s Republic of China has also been an actor in the dispute over the territorial legacy of the former princely state – a fact that has received little attention.

|

Map 1 |

|

Source: Barthi Jain, “Govt Releases New Political Map of India Showing UTs of J&K, Ladakh”, Times of India (online), 2 November 2019, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/govt-releases-new-political-map-of-india-showing-uts-of-jk-ladakh/articleshow/71867468.cms |

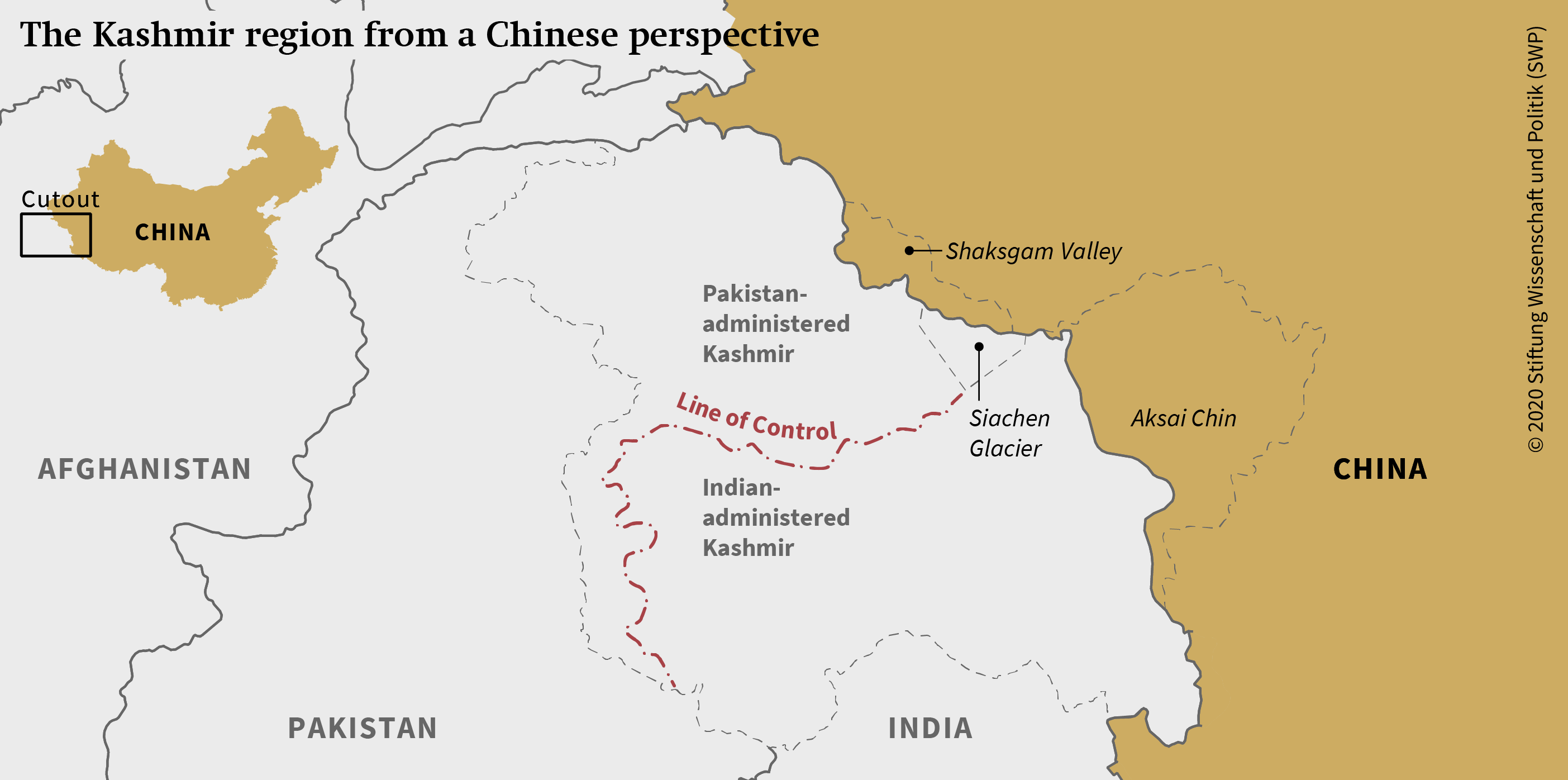

India and China are separated by the longest disputed border in the world, at around 3,500 kilometres. In the Himalayan region, it follows the colonial McMahon Line and is particularly controversial in Kashmir and north-east India. In the late 1950s, China built a permanent road to Tibet through the Aksai Chin region in Kashmir. In 1959, Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai proposed an exchange of territory. This would have given China the Aksai Chin region in exchange for giving up its territorial claims in north-eastern India, now the state of Arunachal Pradesh. However, the Indian government rejected the proposal. After India’s military defeat in the border war of 1962, both sides broke off diplomatic relations, leaving the course of the border unresolved.

Following their political rapprochement after 1988, the question of borders came back into focus. The two countries set up, inter alia, a joint working group to demarcate the border and appointed special envoys. Since then, India and China have concluded a number of agreements (in 1993, 1996, 2003, 2005, 2012, and in 2013) to increase stability in the border region and reduce tensions through confidence-building measures. The 1993 agreement established the current Line of Actual Control (LAC), which is more of a space of mutually accepted patrol routes and military posts rather than a “line”.

The political changes reflected in the new maps and territorial claims since the summer of 2019 seem to herald a new phase in the dispute over Kashmir.

The “Old” Position of India

The point of departure for the new conflict dynamics was the Indian government’s decision on 5 August 2019 to divide the state of Jammu & Kashmir into the two Union territories of J&K and Ladakh. The political leadership of the majority Muslim state of J&K had been granted a number of privileges upon accession, which later led to repeated conflicts between the government in New Delhi and the state government in Srinagar. Kashmir’s special status had been a thorn in the side of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for many years. With its decision, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi was fulfilling one of its election promises. In contrast to federal states, Union territories in India are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Home Affairs in New Delhi.

With this decision, which was based purely on domestic political considerations and communicated in this way to the international community, New Delhi reaffirmed India’s well-known position that all of Kashmir has been formally part of the Union since its accession in October 1947. Thus, in the newly elected assembly of the Union territory of J&K, there are again 24 seats for the Pakistan-controlled part of Kashmir.

The BJP government’s decision sparked strong protests in the former state. Above all, it was an affront to the moderate parties, which had always advocated that the state should remain in the Indian Union, regardless of all political disputes about the form that autonomy should take. In the last state election, in 2014, the voter turnout was over 65 per cent, despite calls for boycotts by Islamist parties demanding accession to Pakistan. Political observers had interpreted this as a clear vote for India.

Pakistan’s “New” Position

With its new map of 4 August 2020, Islamabad underlined its position on the Kashmir issue. Pakistan’s national borders encompass the whole of Kashmir, which confirms the political claim to the territory. Pakistan had ceded the Shaksgam Valley in its part of Kashmir to the People’s Republic in 1963 as part of its political rapprochement with China (see Map 3, p. 6). The Aksai Chin region claimed by China is marked as “frontier undefined”. This corresponded to the position agreed by the two states in the 1963 treaty. Earlier maps, on the other hand, often graphically separated Kashmir – including the GB and AJK regions – from Pakistani territory to indicate that Kashmir is a disputed territory as defined by UN resolutions.

Pakistan has now also changed the nomenclature for the Indian part of Kashmir. The previously used term “disputed territory” was replaced by “Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu & Kashmir”. On the official map, the reference to the UN resolutions can only be found in the Indian part. This implies that the referendum referred to in these resolutions only has to be held in the Indian part. This may be in line with Pakistan’s self-understanding, but the UN resolutions provide for a referendum in the entire former princely state.

Finally, the map also includes areas such as the Siachen Glacier and Sir Creek – in the Indus delta – which have been repeatedly negotiated with India. The renewed claim to the former princely state of Junagadh – located in today’s Indian state of Gujarat, which had joined India after a referendum in 1948 – was also surprising.

Ali Amin Gandapur, Minister of Kashmir Affairs and Gilgit-Baltistan in the government of Prime Minister Imran Khan, announced in September 2020 that the GB region would soon become a province of Pakistan. This has been demanded by the local population for many years. In early November, Prime Minister Khan announced that GB would get the status of a provisional province. The full integration of GB would contradict Pakistan’s traditional position, according to which the question of Kashmir’s final status would only be decided in a referendum. It remains to be seen as to how far the status of a provisional province can be reconciled with the demands of the people in GB. The elections in GB announced for November 2020 could provide further insight into the future status of the region.

In Pakistan it is pointed out that the announcement to make GB a province of its own also benefits China. The lifeline of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – the largest and most expensive single project under the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – runs through the GB region. From a geopolitical perspective, CPEC is a unique project. Although China is Pakistan’s closest ally, it has long advocated a bilateral solution to the Kashmir issue. But this was more in line with India’s position than Pakistan’s. Against this background, the investments in CPEC after 2015 could also be seen as support for the status quo in Indo-Pakistani relations at the time, as it prevailed before BRI began. A stronger constitutional integration of GB would also indirectly secure Chinese investments. After all, the UN resolutions, even if they are only hypothetically relevant, require Pakistan to withdraw from the territory of the former princely state as a precondition for a referendum. Moreover, the Kashmiris could also opt for India in this referendum.

|

Map 2 |

|

Source: Ministry of Defence, Survey of Pakistan. Political Map of Pakistan, 5th edition (2020), http://www.surveyofpakistan.gov.pk/Detail/MTUzYWU5ZGItNTA4NS00MDlkLWFlODctNTRkY2JmNWI0Mjg2. |

The fact that CPEC runs through the Pakistani part of Kashmir is also the main reason why India refuses to participate in the BRI. China had long been courting India’s participation. Because it claims all of Kashmir, the Indian government sees CPEC as a violation of its national sovereignty.

With its new map, Pakistan is reaffirming its political claims on Kashmir, but it is also moving further away from the UN resolutions, despite all statements to the contrary. India’s decision to divide J&K was a welcome opportunity for Pakistan to re-mobilise on the Kashmir issue, which had been relegated to the background in recent years due to economic and political problems. As a result, the hardliners have gained ground in Pakistan as well. Prior to 5 August 2019, Khan had tried several times to resume dialogue with India, but he has since refrained from doing so.

The continuation of the conflict with India is likely to be in the interests of the all-powerful army, which has dominated foreign and security policy towards India for decades. Despite all the economic problems, Pakistan’s defence budget for financial year 2020–21 was increased by 11.9 per cent.

China’s “New, Old” Position

The Chinese government also criticised India’s decision of 5 August 2019 and the creation of the Union territory of Ladakh, which formally includes Aksai Chin. The fact that Ladakh is now centrally administered by New Delhi made it easier for the Indian government to expand the military infrastructure in the region bordering China. China had a clear advantage here, which Indian military experts had repeatedly criticised. After all, there had been repeated incidents in this section of the LAC in the past. Apart from the development of the infrastructure, a statement by the Indian Minister of the Interior, Amit Shah, may have caused annoyance in Beijing. Immediately after his government’s decision, he had reiterated India’s claim to Aksai Chin in Parliament. Chinese experts saw the fact that Chinese troops had crossed the LAC in the Ladakh/Aksai Chin region several times since the beginning of May as a reaction to the Indian decision of August 2019. On 15 June, a serious incident occurred in the Galwan Valley, in which 20 Indian and an unknown number of Chinese soldiers were killed (see SWP Comment 39/2020).

|

Source: “Mapping India and China’s Disputed Borders”, Al Jazeera, 10 September 2020, |

The rhetoric in the Chinese media has become much more intense. India is now portrayed as a provocateur in the border conflict, which legitimises a Chinese reaction in the form of military defence measures. According to a Chinese survey conducted by the party-affiliated magazine the Global Times and the Chinese think-tank CICIR in August 2020, more than 70 per cent of respondents said that India was too hostile towards China; 90 per cent supported retaliatory measures against India.

While tensions in the border region continued, the Chinese side also increasingly emphasised the geopolitical dimension, in particular the intensified military relations between India and the United States and their political cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, including in the framework of the Quadrilateral group (“the Quad”), in which Australia and Japan are also involved.

At the end of September 2020, representatives of the Chinese government surprisingly declared that China’s territorial claims included the territories of the former LAC of 1959. This was China’s first move away from the 1993 agreement that established the current LAC, whose course was never clearly defined. Despite numerous rounds of talks in the past, both sides have never exchanged official maps of the critical areas, including the Ladakh/Aksai Chin region. Therefore, mutual territorial claims have remained vague. With its new position, China resorted to its old one from 1959, which had not been recognised by the Indian government at the time.

Indian military experts have pointed out that since May, violations by Chinese troops have focused mainly on regaining control of the 1959 LAC areas. According to India, China now controls approximately 1,000 square kilometres of territory previously controlled by India.

Outlook

In 2000, US President Bill Clinton described Kashmir as “the most dangerous place in the world”. At the time, this referred to the explosive mix of terrorist attacks and a possible military escalation between the nuclear powers India and Pakistan, which was evident during the Kargil War in 1999 and after the attack on the Indian Parliament in December 2001.

The political changes reflected in the new maps could herald a new phase in the conflict. There is a possibility that the two long-standing conflicts in and around Kashmir could become more intertwined with greater co-operation between Pakistan and China against Indian. Politically, this was already evident in August 2019, when China, in its role as a permanent member of the Security Council, secured an informal meeting of the panel on the Indian decision to dissolve J&K. Although the meeting ended without result, it was celebrated as a great diplomatic success in Pakistan.

China’s claims on the 1959 LAC threaten the infrastructure that India has built up in recent months in some areas. In the event of a military escalation, Chinese troops could block access to Daulat Beg Oldie. The military airfield there is of central importance for supplying Indian troops on the Siachen Glacier. The glacier is the highest war theatre in the world, where Indian and Pakistani troops have been facing each other since the mid-1980s. Apart from the possibility that Pakistan and China might cooperate politically and militarily on Kashmir in the future, recent developments have added another conflict component to the “world’s most dangerous place”. China now no longer sees its border conflict with India as a bilateral problem, but as part of its geopolitical dispute with the United States, in whose camp India is perceived to be. This also affects the LAC in the Ladakh/Aksai Chin region.

The Indian government’s decision to dissolve the state of J&K has therefore proved counterproductive in several respects. Pakistan’s protests were to be expected, and criticism by Western governments and human rights organisations of the massive restrictions of freedoms in Indian Kashmir is unlikely to have impressed the Indian government, nor had it in the past. China’s extreme reaction, on the other hand, which de facto also called into question parts of the bilateral rapprochement of the past 20 to 30 years and probably caused India a permanent loss of territory, had obviously not been anticipated by the Indian side. India’s purely domestic political decision has unintentionally added a geopolitical dimension to the conflict, thereby making it more international – something that Indian governments have so far tried to avoid at all costs.

German and European policy-makers are likely to have problems with the positions of all parties to the conflict. During her visit to India in November 2019, German Chancellor Angela Merkel described the situation in Indian Kashmir as “untenable” because massive restrictions on civil rights were imposed there after the country’s transformation into a Union territory. Pakistan’s attempts to internationalise the conflict will still find hardly any support in Berlin and Brussels. Beijing’s efforts to restore the current 1959 Line of Control, in turn, will not diminish the growing reservations about the matter in Germany and Europe.

Although Berlin and Brussels share an interest in regional stability, they have little opportunity to influence the parties to the conflict. The approach agreed by India and Pakistan in 2007 was essentially to establish the political and territorial status quo in Kashmir. In the new conflict scenario, a solution between the governments involved is likely to be a long way off. Kashmir has a different strategic importance for the three states. For India, it was, is, and remains a purely domestic issue. The new developments once again offer Pakistan the opportunity to mobilise nationally and internationally for its cause. For China, the conflict is a new stage in the geostrategic struggle, especially in terms of its foreign policy: It is wrestling not only with India over the future role of both states in South Asia, but also indirectly with the United States over who holds power in the Indo-Pacific.

Dr Christian Wagner is Senior Fellow in the Asia Division at SWP.

Dr Angela Stanzel is Associate in the Asia Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2020

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN 1861-1761

doi: 10.18449/2020C52

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 85/2020)