Almost eight months into the offensive on Tripoli by Khalifa Haftar’s “Libyan Arab Armed Forces” (LAAF), the war shows no signs of abating. Ongoing diplomatic efforts are divorced from realities on the ground. The current balance of forces rules out any possibility for a return to a political process. This would require either robust international guarantees or a fragmentation of both opposing camps. As long as Haftar has the chance to advance in Tripoli, he and his foreign supporters will view negotiations as a tactic to divide his opponents and move closer to seizing power. To create the conditions for negotiations, Western states should work to weaken Haftar’s alliance – and ultimately to prepare the post-Haftar era.

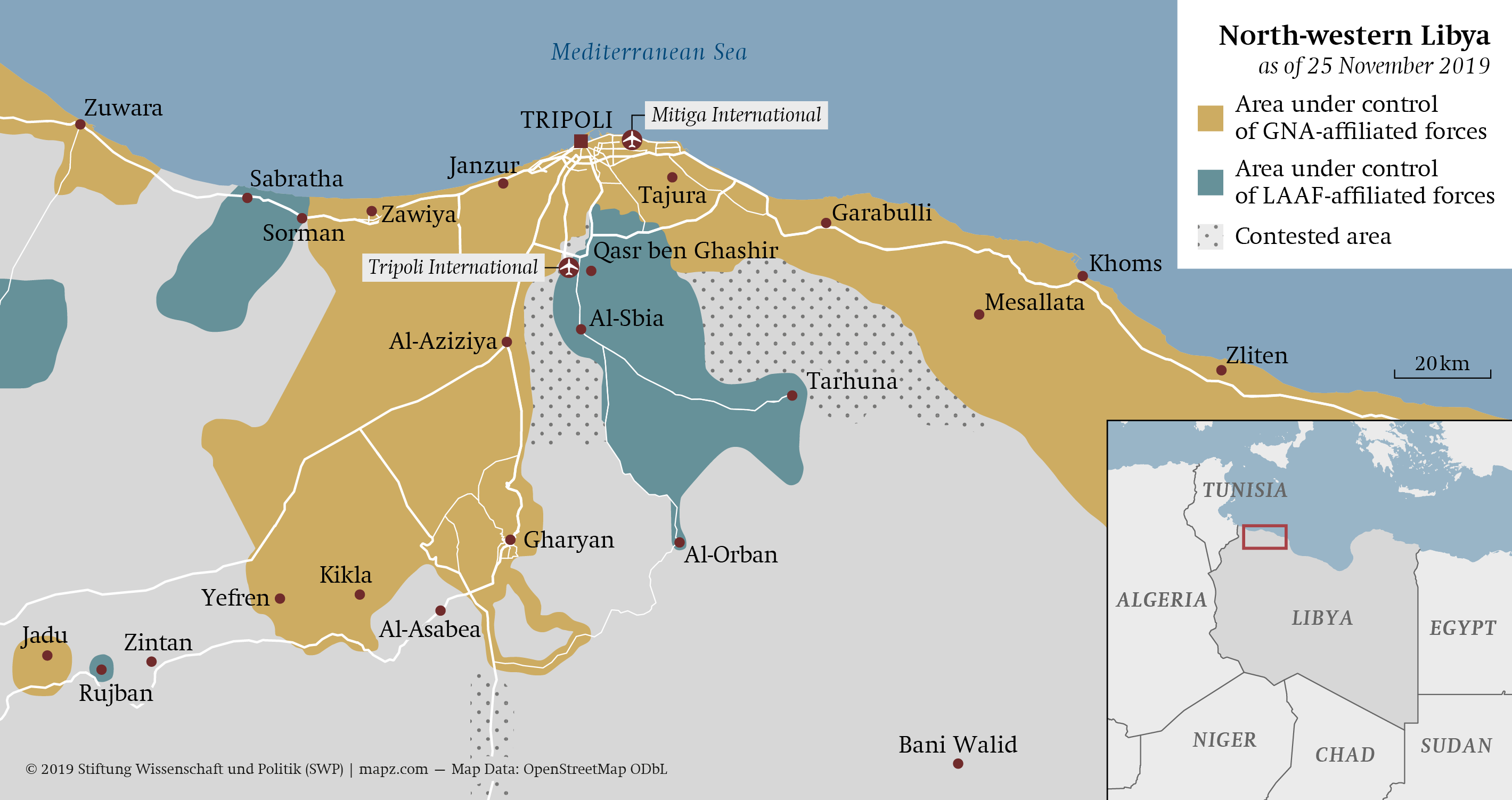

After the first few days of the offensive in April, Haftar’s forces for months made no more territorial gains in Tripoli. Nor were Haftar’s adversaries – an alliance of armed groups from western Libyan cities that go back to the 2011 war against Qadhafi – able to repel the attackers. The recapture of Gharyan in late June 2019 was the last major success of the anti-Haftar forces. Since he lost Gharyan, Haftar has been relying solely on Tarhuna as the base for his ground offensive. The militia of the Kani brothers in that city has come to play a central role in Haftar’s alliance.

As the war has dragged on, foreign military support has become ever more important for both sides. At the same time, inhibitions towards causing civilian casualties have steadily fallen. In mid-April, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) started using combat drones in support of Haftar. His adversaries pulled even in mid-May by obtaining combat drones from Turkey. Since late June, UAE fighter jets have also repeatedly bombed Haftar’s opponents. The UAE gradually established air superiority; Turkish drones have largely stopped operating.

Despite this, Haftar has made little progress because he has been unable to mobilise greater numbers of determined Libyan fighters. His forces include units he built up during recent years in eastern Libya as well as western Libyan armed groups, whose loyalty to Haftar is often doubtful. Among them, hardline Salafis and former supporters of the Qadhafi regime form prominent subgroups.

To boost his forces, Haftar has deployed ever more Chadian and Sudanese fighters – but most importantly the mercenaries of the Russian private military company Wagner, who arrived in Tripoli in September, and by mid-November numbered well over 1,000 men. Only with this Russian contingent, which was undoubtedly approved by the Kremlin, was Haftar able to regain the offensive during November. But his modest advances came at the cost of US permissiveness towards Haftar’s offensive. Alarmed over the Russian mercenaries, the United States called on Haftar to end his offensive. It remains unclear whether further steps will follow that call.

The long stalemate caused war fatigue among armed groups on both sides. Haftar’s increasing reliance on foreign mercenaries is a case in point. Among his adversaries, there are growing accusations that the Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli lacks determination in the fight against Haftar, is failing to mobilise the needed weaponry from abroad, and that many of its members are busy with self-enrichment, or even complicit with Haftar. Mobilisation for the defence of Tripoli has declined in recent months. Since the frontlines had not seen any real changes in months, many no longer saw the urgency of the situation. Major advances by Haftar would likely prompt renewed mobilisation.

War of Attrition

As the stalemate persists, each side hopes that the opposing camp will fragment at some point. These hopes are not entirely baseless, but they are often misplaced.

Haftar is waging a war of attrition against his opponents, with generous foreign support: The Chinese-made Emirati drones are clearly superior to the Turkish model, and the Russian air-defence batteries provided by the UAE give Haftar’s bases an important advantage. Haftar is seeking to slowly degrade his adversaries’ capabilities with relentless airstrikes. This assumes, however, that the Tripoli government will not get better at replacing destroyed weapons and vehicles.

Haftar and his foreign backers also expect that some militia leaders in the enemy camp may soon switch sides. In fact, this has been unlikely since the beginning of the war: Defectors cannot trust Haftar to keep any promises he makes now, once he has won.

It is true that Haftar’s enemies are only united by the threat he poses to them. There are real tensions between some of the component elements in the anti-Haftar alliance. Past conflicts and expectations of future rivalries fuel distrust between them, but the opportunism of these forces is often overestimated. Most commanders and fighters not only firmly believe that they are fighting for a just cause: against the establishment of dictatorship by force. Many of them are also deeply rooted in the social fabric of particular cities and are convinced that they are defending their families and communities. If they lose the war against Haftar, they will have to flee abroad. It is therefore unlikely that Haftar’s opponents will give in easily.

The forces fighting Haftar are placing their hopes in ceasefire negotiations with militias from Tarhuna that would sideline Haftar. This idea does not lack plausibility: Local ceasefires also ended the last civil war, in 2015. The Kani brothers’ militia only joined Haftar’s alliance with the start of his Tripoli offensive and had previously been opportunistic in the choice of its allies. Contacts between forces in the anti-Haftar camp and representatives of Tarhuna have never broken off; attempts at negotiations continue. But for these to progress, two conditions would need to hold: First, Haftar would need to suffer reversals that would increase pressure on Tarhuna – which is currently not the case. Second, Haftar’s opponents would need to guarantee that they will not try capturing the city once it has broken with Haftar. This would require the deployment of units that enjoy respect on both sides.

The Berlin Process

In September 2019, UN Special Representative Ghassan Salamé and the German government launched the Berlin process, a series of consultations between the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and the states intervening in Libya. The initial aim was to hold a high-level conference at which these states would commit to discontinue their support to the warring parties and respect the arms embargo. This was to create the conditions for a ceasefire and a return to a Libyan political process.

However, among Haftar’s foreign supporters, Egypt, France, and the UAE pushed to expand the agenda beyond the issue of foreign meddling to include the outlines of an intra-Libyan settlement. Suspending UAE drone strikes while fighting continues on the ground would probably lead to Haftar’s defeat. These states therefore cannot trust that an end to foreign meddling would lead to a negotiated settlement favourable to them. As a result, the discussions have come to include ceasefire arrangements, the contours of a political process, and certain “reforms” that Haftar’s backers see as part of a settlement. These notably include easier access to Central Bank resources for Haftar – through the restoration of the board of governors of the Central Bank and its absorption of debt accumulated in eastern Libya over recent years – and the demobilisation of “militias”, by which Haftar’s supporters only mean those of his adversaries.

The international alignments reflected in the Berlin process mean that Haftar’s opponents would need to make major concessions in exchange for a ceasefire. At the same time, Haftar’s forces would remain in greater Tripoli – if only because militias from nearby Tarhuna are there anyway.

Such ideas are incompatible with the options open to Haftar’s opponents – who, like other Libyan parties, are not participating in the Berlin talks. The anti-Haftar alliance is fragile and lacks strong political leadership. Should some of its representatives accept an unconditional ceasefire – let alone more wide-ranging concessions – the alliance would splinter into proponents and opponents of such a deal. Latent distrust would turn into open enmity. The fragmentation of his opponents would allow Haftar to move forward militarily and persuade some of his enemies to switch sides. Under current circumstances, talks with Haftar would therefore be fatal for his opponents – and they are acutely aware of this danger.

The launch of the Berlin Process was based on the assumption that, after months of war, Haftar’s foreign backers had concluded that a military victory was unrealistic, and they would therefore be ready to negotiate. This assumption was wrong, as shown not only by the arrival of Russian mercenaries since September. France, Egypt, and the UAE also appear to view negotiations merely as a step towards Haftar’s capture of power. There is no reason to believe that these states have now abandoned their longstanding goal of empowering Haftar.

If a minority among the forces fighting Haftar were to agree to a ceasefire and negotiations, this would not bring about an end to the conflict. Rather, it would risk ushering in a much more violent phase of the war. Haftar could exploit tensions among his opponents to advance into densely populated neighbourhoods of Tripoli. There, the conflict could take a much higher toll on civilians. If Haftar actually ends up taking control of Tripoli – after months or perhaps years of fighting, which would cause major destruction – he will not yet have captured the cities that form the strongholds of his opponents: Misrata, Zawiya, and the Amazigh towns. Yearnings for revenge against these communities are widespread in his alliance. Attempts to subjugate these cities would certainly see war crimes and arbitrary repression.

Alternatives

A political solution will only become imaginable once Haftar no longer has the possibility of using negotiations to exploit rifts among his opponents for military gains. There are two conditions that could prevent him from doing so. First, the United States and European states offer robust guarantees that they will prevent Haftar from violating a ceasefire. This would require much more than words, as the United States, the EU, and the UN lost most of their remaining credibility in Libya when they failed to react to Haftar’s offensive. Merely supervising the ceasefire with civilian observers and aerial photography would fail entirely to offer security. But a peacekeeping mission is currently not on the table.

The second possible condition would be that Haftar’s alliance fragments as well, removing the threat of a renewed offensive following negotiations. This could happen as a result of military reversals and local negotiations in western Libya, or if his foreign backers change course – by diversifying their Libyan clients, or in response to increased Western pressure. The United States would certainly need to play a key role in this regard, particularly to contain Russian influence. That said, the current administration will hardly pursue a predictable and consistent Libya policy.

But Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, and other European states could also exert more influence than they have done to date – by engaging more intensively with France. French political backing for Haftar’s war clearly harms European interests. France’s European partners have rarely addressed this issue openly, and there has been little public debate about it in France. This is largely due to the discretion with which the French government has pursued its line since French weapons were found in Haftar’s Gharyan base in June 2019, briefly raising eyebrows. Opening up a debate on this policy would force the French government to explain its position. The aim should be a unified European approach towards Haftar’s foreign supporters.

A fragmentation of Haftar’s alliance could also weaken his authority in the east and cause renewed instability there. But given that Haftar is 76 years old and reportedly ill, this is a likely scenario anyway. For now, the personality cult surrounding Haftar and the repressive apparatus run by his inner circle hold the conflicting interests in his eastern alliance together. But Haftar’s departure could at any moment provoke a scramble to fill the vacuum. Preparing the post-Haftar era would be a more sensible realpolitik than helping to empower him by watching the current war to its bitter end.

Dr. Wolfram Lacher is a Senior Associate in the Middle East and Africa Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2019

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN 1861-1761

doi: 10.18449/2019C45

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 65/2019)