From Frontline to Central Regional Node: Turkey’s Recalibration of its Regional Strategy in Iraq

SWP Comment 2025/C 43, 02.10.2025, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2025C43

Research AreasOnce viewed by Ankara primarily as a fragmented security frontier, Iraq now sits at the centre of its regional strategy. This recalibration is shaped by shifting regional dynamics in the aftermath of 7 October: the weakening of Iran’s influence across multiple fronts, the Gulf states’ rising economic and diplomatic weight, and the search for new stabilising axes in the Middle East. Turkey’s renewed engagement is not just about countering the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) – it signals broader regional aspirations that combines security cooperation with Baghdad and Erbil, a fragile domestic peace process in Turkey, and a strategic push to embed Iraq within Turkey–Gulf trade and key regional energy infrastructures, including oil pipelines, prospective gas exports, and electricity interconnections. At the heart of this shift is a geoeconomic logic: by investing in shared infrastructure and fostering mutual interdependencies, Ankara seeks to consolidate its regional role. For Europe, the outcome will reverberate beyond Iraq by reshaping connectivity, energy access, and the stability of its south-eastern neighbours.

After decades of turbulence, Ankara and Baghdad have embarked on a strategic thaw, anchored in high-level visits and a flurry of agreements. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s April 2024 visit to Baghdad (his first in 13 years) produced 26 agreements; Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani’s reciprocal trip to Ankara in May 2025 added 11 more. Turkish officials now describe Iraq as a strategic partner and a central actor in regional stabilisation, reflecting a new narrative framing Iraq as essential for regional security, trade, transregional connectivity, and energy integration. This momentum signals Ankara’s shift towards a more structured, multidimensional partnership with Iraq, encompassing the ongoing flagship Development Road Project that seeks to connect the Persian Gulf to Turkey, renewed energy cooperation on the Kirkuk–Ceyhan pipeline, expanded trade, and enhanced security coordination.

Turkey’s recalibration towards Baghdad is unfolding amid a series of profound regional upheavals including the Israel–Gaza war, the Iran–Israel escalation, and the fall of the Assad regime, which are reshaping power dynamics across the Middle East. Ankara sees an urgent need to secure Iraq’s cooperation to contain threats from the PKK and to recalibrate relations with Iranian-backed Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), as concerns grown that the country could become the next arena of confrontation between Israel and Iran.

Beyond a security lens, Ankara’s renewed engagement with Baghdad coincides with a broader rapprochement with Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). As such, Ankara embeds Iraq within emerging ad hoc regional frameworks that link trade, connectivity, and regional stabilisation. This alignment expands Turkey’s strategic influence while also diluting Iran’s centrality in shaping Iraq’s regional affiliations.

Ankara’s recalibrated approach on Iraq also reflects its broader foreign policy shift following the 2023 elections, which extended the mandate of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government until 2028. At its core is an economy-centred orientation to foreign policy, a focus on regional ownership, diversification of partnerships with regional actors and the pursuit of energy, trade, and logistics/connectivity projects.

All of these factors coalesce in Iraq. Far from an isolated adjustment, it is part of a wider geopolitical reorientation in which Iraq is positioned as both a security partner and a geoeconomic node linking the Gulf, the Levant, and Anatolia.

Re-thinking Security beyond Zero-Sum Calculations

For much of the post–Cold War period, Ankara viewed Iraq primarily through a threat-centric lens, shaped above all by the PKK’s sanctuary in the Qandil Mountains and the autonomy aspirations of Iraqi Kurds – developments feared to embolden separatism within Turkey. The 2003 United States (US) invasion accentuated Ankara’s perception of Iraq as an even more unstable and high-threat neighbour. Turkey found itself strategically estranged from both its Western allies, particularly the US, and new political actors emerging in Baghdad, while Iran’s ascendancy further diminished Ankara’s footprint in Iraq.

Strategic estrangement with Washington set in immediately with Turkey’s refusal to open a northern front for US forces in March 2003. The incidents such as the April 2003 seizure of a Turkish Special Forces truck and the July 2003 detention of Turkish personnel in Sulaymaniyah, commonly known as the “Hood Incident” compounded the situation. The PKK’s return to militant activities in 2004 hardened Ankara’s threat perceptions, while resistance from both Shi’a Arabs and Kurds to any Turkish military role – rooted in fears of revived Ottoman ambitions – kept Turkey sidelined from Iraq’s post-war reconstruction and political transition.

Iran’s growing influence after 2003 cemented this security-first view. The expansion of the PMF into contested areas such as Tal Afar and Sinjar during the fight against the Islamic State (IS) brought Iranian influence closer to Turkey’s borders, overlapping with PKK strongholds and creating what Ankara perceived as a dual security threat. Confronted with this nexus of PKK, Shi’a militias, and Iran, since 2016 Turkey has increasingly relied on unilateral military operations, the establishment of forward-operating bases in northern Iraq, and deepened engagement with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Today, Ankara is seeking to overcome its estrangement in Iraq by rebranding its military activities within the language of joint security arrangements rather than unilateral prerogatives. With this, Ankara hopes to gain legitimacy for its military presence in Iraq and address Baghdad’s sovereignty sensitivities, even though Turkey’s cross-border operations and the contested reception of its bases on Iraqi soil continue to complicate matters. In 2024, Ankara and Baghdad agreed to establish a Joint Security Coordination Centre in Baghdad and convert the long-contested Turkish base in Bashiqa into a Joint Training and Cooperation Centre under Iraqi command. Turkish officials present this shift not as a withdrawal but as a strategic repositioning towards co-managed security by maintaining operational presence while granting Baghdad formal authority.

This strategy also aims to secure Baghdad’s backing of its campaign against the PKK. Iraq’s 2024 announcement to ban the PKK, Bagdad’s silence over Turkish military operations in 2024 and 2025, and Prime Minister al-Sudani’s remark on their commitment of preventing Iraqi territory from being used by non-state actors point to a fragile and unprecedented alignment. The PKK’s May 2025 declaration of disarmament and eventual dissolution, and the initiation of a disarmament process involving Turkish intelligence and Iraqi mediators, further reinforced this foundation.

At the same time, Ankara seeks a role in Iraq’s emerging security architecture by offering military training, arms sales, and institutionalised cooperation. Since 2024, regular working-level exchanges have covered PKK, IS, border management, migration, and criminal extradition. Turkish National Intelligence Organization chief İbrahim Kalın met Iraqi Prime Minister Sudani in July 2025 to enhance intelligence-sharing and border stability. Breaking years of deadlock over arms deals, the two countries also signed a defence industry cooperation pact in May 2025 which includes the transfer of Turkish defence technology. Following this, the state-owned, Military Factory and Shipyard Management Inc. (ASFAT), inked a deal for artillery ammunition production in Iraq. Turkey now offers Iraq military training, defence products, intelligence sharing, joint operational planning, and coordinated responses to shared threats.

Balancing Iran and Leveraging Geopolitical Shifts

Ankara’s recalibration towards Iraq also aims at positioning Baghdad as a strategic fulcrum in Turkey’s broader effort to counterbalance Iran. After 2003, Iran’s dominance in Baghdad confined Turkey’s influence to narrow constituencies, namely Turkmen communities, select Sunni tribal networks, and the KRG. This asymmetry reinforced the security frontier paradigm, in which Iraq was treated less as a partner and more as an area of contested terrain to be contained or bypassed.

Ankara has long sought to overcome this estrangement with Baghdad. A notable opening came after the KRG’s September 2017 independence referendum, when Ankara aligned with Baghdad against Kurdish secession and supported the central government’s retaking of Kirkuk from Kurdish forces. This marked the beginning of Turkey’s gradual re-engagement with federal authorities in Baghdad. The urgency grew with the prospect of US troops shifting from combat to advisory roles as of 2021, prompted by domestic pressure in Iraq for a full US withdrawal after the January 2020 killings of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani and the Deputy Head of the PMF, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. For Ankara, the risk was that Iran would fill a vacuum, whereas the opportunity was to institutionalize security, trade, and connectivity with Baghdad before that happened. Against this backdrop, Ankara now sees strategic openings created by the fall of Syria’s Assad regime, Iran’s defeat in the June war against Israel, the losses of Iran’s axis of resistance, and Israel’s continued pressure on Hezbollah. Tehran’s weakening regional leverage perceived as an opportunity for Turkey to expand its influence through new alignments and institutional footholds.

Leveraging these shifts, Ankara seeks to integrate Iraq into its wider regional ambitions by linking security cooperation to infrastructure development and positioning Baghdad as both a partner in balancing Tehran and a hub for energy, trade, and stabilisation. One instrument is the Turkey–Iraq–Syria–Jordan–Lebanon security format, launched in 2025 to manage IS in the region. At the March 2025 Amman meeting, Turkey, Syria, and Jordan agreed to establish a Joint Operations Centre to coordinate counterterrorism and management of prisons holding IS fighters and camps such as Al Hol and Roj that house IS‑affiliated women and families, many of whom remain under the guard of the US‑allied Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Turkish officials view the SDF as the PKK’s Syrian offshoot and hope that this regional security format can help transfer these camps to the new Syrian government thereby severing logistical links between the PKK and SDF – particularly in Sinjar, a vital corridor between Iraq and Syria.

The same corridor was once Iran’s land bridge connecting its regional networks of non-state allies and proxies in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon until the fall of Assad. It still holds geopolitical importance as evident in June 2025 when just one day after the outbreak of the Israel–Iran war, Syria deployed 3,000 troops to the Iraqi border to deter infiltration by pro-Iran Iraqi militias. In this sense, Ankara aims to leverage this framework to align Iraq and Jordan – both wary of the uncertain Syrian transition – behind a coordinated security agenda. This includes tightening border control, countering extremist groups such as IS, and jointly managing aspects of the security vacuum left by Russia and Iran in Syria.

The Development Road Project as a Strategic Pivot in Regional Connectivity

Still, Turkey’s new approach to Iraq is not only driven by its intensified rivalry with Iran. It is also a response to Ankara’s perceived marginalisation by the US-led India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Ankara promotes the Iraq-based Development Road Project as an alternative to IMEC, aiming to secure its geoeconomic relevance, while simultaneously counterbalancing Iran’s influence and deepening ties with Gulf partners.

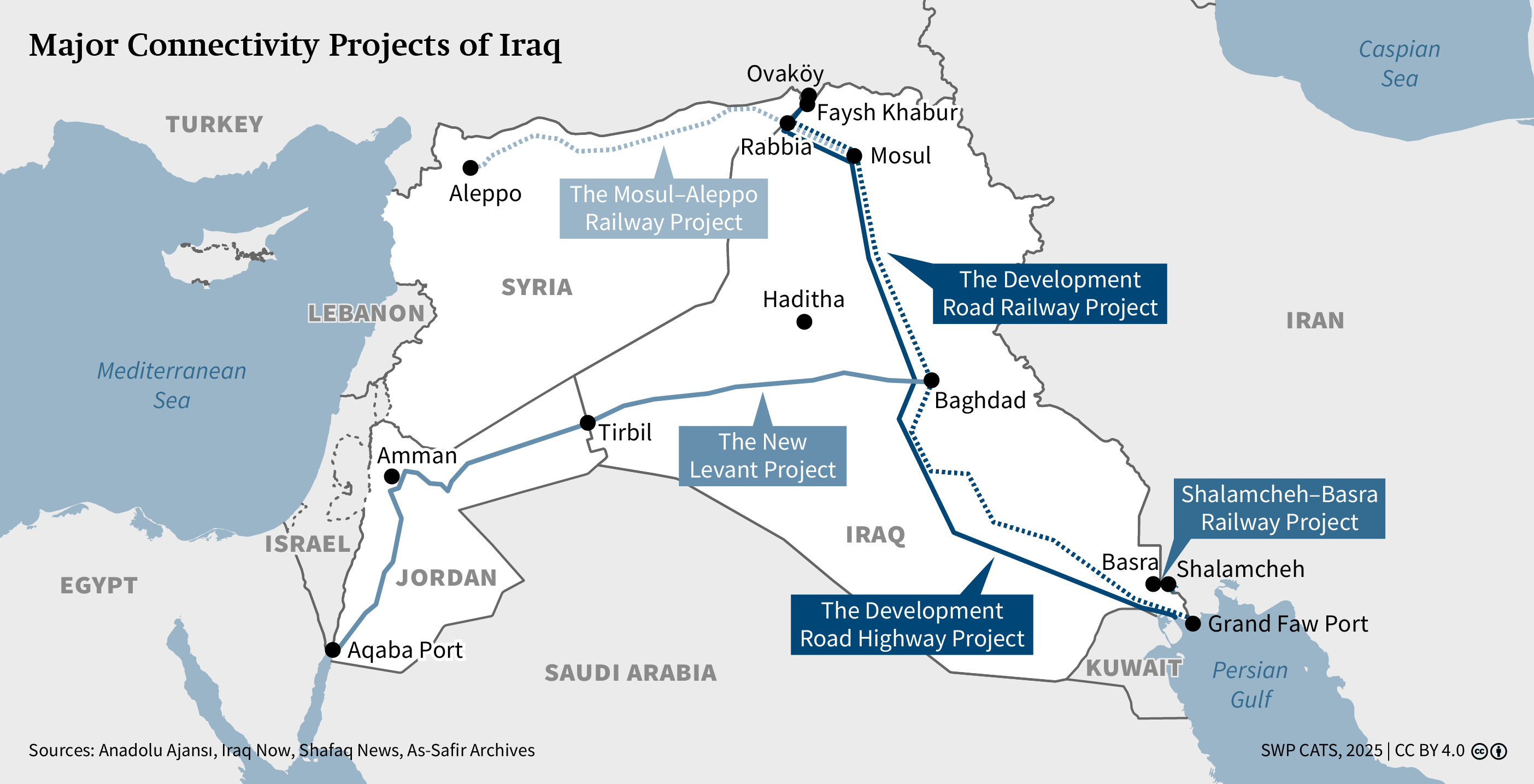

Linking Basra to Turkey, this mega logistics project positions Iraq as a linchpin in Ankara’s east–west connectivity vision, complementing the Middle Corridor that runs through Central Asia and Turkey. The Al Faw Grand Port is envisaged as a regional logistics hub, anchoring a 1,200-kilometer corridor from Basra to the Turkish border. Turkey is simultaneously upgrading domestic infrastructure and cross-border logistics, such as in Habur–Faysh Khabur and Ovaköy, to ensure seamless integration with European Union (EU) customs zones.

The initiative that reinforces Turkey’s geopolitical role as a European bridge also embodies Ankara’s broader interconnectivity strategy, which seeks to build ad hoc regional alignments along the Turkey–Iraq–UAE–Qatar axis. In April 2024, Turkey and Iraq signed a memorandum of understanding with Qatar and the UAE, followed by a summit in Turkey in August to discuss financing, construction, and governance. Facing financial constraints, Ankara relies on Gulf investment to share costs, spread political risk, and secure regional buy-in. Such backing, especially from the UAE and Qatar, not only funds Iraqi infrastructure but also grants political legitimacy, embeds Iraq within wider economic frameworks, while helps Turkey to outmanoeuvre Iran’s east–west corridors that also bypass Turkey.

This geoeconomic turn marks a decisive shift from Ankara’s earlier ideology-driven regional politics towards a pragmatic focus on infrastructure, trade routes, and regional economic integration. By embedding Iraq and its Gulf partners in shared infrastructure, Ankara aims to create mutual dependencies that lock them into a Turkey-centric economic zone. To this end, Ankara is mobilizing its logistics capacity and construction sector, framing the project as cost-effective, faster, and a regionally owned, strengthening its role in shaping the future of Middle Eastern connectivity.

Economic Statecraft for Strategic Integration

Such an economy-centred foreign policy is unsurprisingly underscored by efforts to expand trade and investment, as well as to achieve deeper market integration with Iraq. Bilateral agreements signed in 2024 included provisions to improve customs procedures and reduce trade frictions, while also addressing land transport bottlenecks through the proposed Ovaköy border crossing north of Mosul, which was intended to complement the congested Habur–Zakho route. Turkish goods ranging from food products to household appliances already dominate significant segments of the Iraqi market, benefiting from competitive pricing and logistical proximity.

Beyond transit infrastructure, Ankara’s vision of a “dry canal” corridor encompasses the development of logistics hubs and industrial zones along the route, where Turkish firms are well positioned to lead. This approach aims to embed Turkish industry more deeply in Iraq’s reconstruction and economic transformation. Turkish companies have already invested an estimated $35 billion, with bilateral trade surpassing $15 billion in 2024. In early 2025, the two governments began drafting a roadmap to further expand trade volumes and mutual investment. Crucially, Ankara also seeks to extend its economic reach beyond Iraq’s Sunni regions into the Shi’a south through inclusive investment offers.

Yet economic integration is not pursued solely as cooperation: It is also a tool of leverage. Turkey has combined incentives, such as infrastructure promises to Baghdad and Erbil, with punitive measures. This is most visible in its 2023 closure of airspace to Sulaymaniyah. Ankara justified this step by accusing the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) of close ties with the PKK. The move particularly aims to put economic pressure on the PUK, which is the ruling party in the southern part of Iraqi Kurdistan. In this sense, Ankara’s economic statecraft operates on two tracks: rewarding alignment with projects and access, while constraining rivals through economic pressure.

Energy Diplomacy as Regional Leverage

Having placed Iraq at the centre of its connectivity strategy, Ankara is extending the same logic to energy, where pipelines and transit routes serve as both economic assets and instruments of geopolitical influence. Iraq’s oil and gas reserves, integrated into expanded infrastructure, are central to Turkey’s ambition of becoming a regional energy hub. This would enhance its leverage, diversify supply routes, and position the country as a key player in Europe’s energy security. To this end, Ankara has sought to strengthen its existing network – including the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), TurkStream, and the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan line – to connect Middle Eastern and Caspian resources with European markets while reducing energy dependence on Russia and Iran.

Within this context, the resumption of oil flows through the Kirkuk–Ceyhan pipeline has become a central priority. The pipeline has been idle since March 2023, following an international arbitration ruling brought by Iraq and resulting in a $1.5 billion penalty for unauthorised Kurdish oil exports between 2014 and 2018. In response, Ankara cancelled the 50-year-old pipeline agreement in July 2025 and signalled its readiness to negotiate a new framework – one that recognizes Baghdad’s authority over exports, establishes a revenue-sharing mechanism, and ensures supply stability. In September 2025, Baghdad and the KRG reached a deal to resume pipeline exports to Turkey, marking a tentative step towards restoring flows. While Turkey continues to appeal the arbitration ruling, it has expressed a willingness to resume flows under a restructured arrangement that integrates the pipeline into a broader regional infrastructure vision.

Building on this momentum, Ankara submitted a comprehensive draft agreement to Baghdad to expand bilateral energy cooperation. The proposal goes beyond oil to include natural gas, petrochemicals, and electricity, reflecting the widening scope of Ankara’s energy diplomacy. Crucially, it is designed to complement the Development Road project by aligning energy transit infrastructure with the connectivity corridor. Turkish Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar noted that the plan also foresees extending the pipeline to Iraq’s southern oil fields, thereby increasing capacity and establishing direct linkages between southern Iraq and Turkish ports. For Ankara, this would not only diversify Iraq’s export routes, but also embed it more deeply within Turkey’s regional energy network – enhancing both Ankara’s hub ambitions and its geoeconomic influence at a moment of heightened regional instability stretching from the Strait of Hormuz through Red Sea.

Turkey’s Iraq Gamble: Between Opportunity and Risk

Notwithstanding the opportunities involved, it is uncertain if Turkey’s calculated gamble towards Iraq would yield the desired outcomes. The gamble lies in Ankara’s assumption that embedding itself through joint security arrangements, infrastructure projects, and energy cooperation would not only deliver long-term bilateral gains, but also secure its place in the emerging regional order. Yet this wager is being made against a backdrop of Iraq’s political fragility, volatile security environment, and entrenched regional rivalries – factors that could easily derail Ankara’s ambitions. Still, it is a calculated gamble because Ankara has hedged its bet. By combining military cooperation with economic entanglement, drawing in Gulf partners to share costs, and reaching out for several Iraqi actors – including potential spoilers like the PMF – to become stakeholders, Turkey seeks to reduce the risk of outright failure even amid Iraq’s political fragility and entrenched rivalries.

Security represents a second uncertainty. Planned initiatives, such as large sections of the Development Road corridor, energy infrastructure, logistic hubs, and industrial zones cut through areas scarred by conflict where stability remains fragile. The PMF in southern and northern Iraq could obstruct progress if Tehran views the project as undermining its influence. Likewise, PKK activity in Sinjar and Makhmour continues to threaten construction and long-term security in northern Iraq. Turkey’s continued reliance on unilateral military operations – particularly airstrikes or cross-border incursions – risks triggering backlash from Iraqi political actors, Shi’a militias, and segments of the public sensitive to sovereignty violations, which has the potential to derail the broader rapprochement and undermine joint initiatives.

Yet, recent developments tilt the balance somewhat in Ankara’s favour. The PKK’s announced dissolution and Turkey–Iraq rapprochement create a more favourable backdrop. At the same time, the PMF, which controls much of Iraq’s infrastructure and borders, may increasingly calculate that the project offers them economic gain through revenues, jobs, and wider activity, potentially shifting their role from spoiler to stakeholder.

The gamble is equally visible in Ankara’s attempt to leverage Iraq as a counterweight to Iran. With Tehran weakened in the region, Turkey sees greater room to manoeuvre. Yet Iran’s entrenched networks through the PMF, clerical authorities, and political patronage remain formidable. Any overt Turkish attempt to sideline Tehran risks destabilizing Sudan’s balancing act and triggering backlash from Iran’s proxies. For Ankara, the gamble here is not eliminating Iranian influence outright but ensuring that Turkey’s role is entrenched enough to withstand future Iranian pushback.

Mega-projects like the Development Road Project illustrate both the promise and peril of Turkey’s strategy. While, such projects offer the potential to reshape regional connectivity, embed economic interdependence, and elevate Ankara’s strategic role, they expose Turkey to rising financial costs, political volatility in Iraq, and resistance from rival actors such as Iran or domestic spoilers like the PKK. If completed, the Basra–Turkey corridor would reposition Iraq as a hub of regional connectivity, tie Gulf capital to a Turkey–Baghdad axis, and secure Ankara a decisive role in east–west trade. But rising costs – such as the Development Road Project already estimating to cost beyond the initial $17 billion estimate – and Iraq’s fragmented politics underscore the fragility of these ambitions.

In sum, Turkey’s Iraq gamble is part of a wider regional trajectory in which in which the order of political power is increasingly built through ad hoc coalitions, connectivity projects, and investment-driven interdependence. It is less of a zero-sum bet and more of a layered strategy designed to limit losses and guarantee some return. Whether it yields a breakthrough or settles into another cycle of modest but enduring gains will depend as much on Iraq’s political resilience as on shifting regional rivalries.

Why This Shift is also Strategic for Europe

Turkey’s recalibration towards Iraq is not an isolated policy adjustment. Instead, it is part of a broader strategic shift in response to a changing regional landscape. Iran’s regional network, the emergence of the Gulf states as key economic and political brokers, and Ankara’s own peace process with the PKK have opened new avenues for Turkey to reposition itself as a central actor in regional security and connectivity. Iraq has become the linchpin in this effort, which is a test case for Ankara’s attempt to institutionalize influence through security cooperation, economic interdependence, and infrastructure integration.

While this emerging Turkish posture may not be fully aligned with European preferences – particularly given scepticism towards Turkey’s regional ambitions – it remains strategically relevant for the EU. For one, a reduction in PKK-related tensions, if sustained, would remove a long-standing irritant in EU–Turkey relations, even if the unresolved dynamics in Syria continue to complicate the picture. Most importantly, Iran’s defeat may be viewed positively in European capitals, which remain concerned about Tehran’s role in regional destabilisation and nuclear proliferation.

Yet, the core challenge for Europe lies not in Turkey’s ambitions per se, but in whether and how those ambitions reshape the regional order in ways that either complement or constrain European interests. Together with Gulf partners, Turkey and Iraq are developing logistics hubs, industrial zones, and cross-border trade routes, including a strategic land bridge offering an alternative to maritime chokepoints like the Suez Canal. Some EU Member States already see investment opportunities in these regional initiatives. The policy challenge for Brussels is how these national economic interests can be mobilized collectively within the EU’s external policy framework.

Turkey’s growing role in Iraq’s energy and infrastructure sectors, for instance, may not directly serve the EU’s long-term diversification strategy, which is increasingly oriented towards the South Caucasus, Central Asia, and transatlantic liquified natural gas. Nonetheless, these developments could carry tactical significance for near-term supply stability, regulatory influence, and geopolitical resilience – especially amid ongoing instability in the Red Sea, Eastern Mediterranean, and the Gulf. Even if Europe is unlikely to make Iraq a pillar of its diversification policy, the stabilisation of Iraqi energy flows and their integration into Turkey’s infrastructure still intersect with European interests in near-term supply security and regional energy governance, not least by reducing Turkey’s overdependence on Russian and Iranian energy supplies.

Moreover, Turkish efforts to integrate Iraq into its hub strategy that links pipelines, electricity grids, and petrochemicals with Gulf and Anatolian infrastructure create new interdependencies that Europe cannot ignore. Engagement here could give Brussels a role in shaping governance, revenue-sharing, and sustainability standards for projects that impact the EU’s energy mix.

Security interdependence follows a similar logic. The US withdraw, volatile security environment, and possible Iranian retaliation in Iraq, whether against US military strikes, Israeli operations, or renewed sanctions pressure, is exposing the North American Treaty Organization (NATO) and EU advisory missions to growing operational and security risks. While European allies have signalled greater commitment to sustaining these missions, persistent limitations, ranging from national caveats to divergent threat perceptions, continue to undermine coherence and effectiveness. In this evolving landscape, Turkey’s deepening engagement with Baghdad in the security realm alongside its broader infrastructure and economic initiatives introduces a new layer of complexity. More importantly, NATO’s assets in Turkey– Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft stationed at Konya, logistical depth through İncirlik, and missile defence radar at Kürecik – provide the Alliance with critical enablers for situational awareness, force protection, and operational flexibility. These functions, rather than direct combat support, are likely to become increasingly relevant for the future viability of NATO mission Iraq and for the EU’s ability to sustain its engagement in Iraq.

At a deeper level, Ankara’s posture reflects the rise of regionally owned, minilateral diplomacy schemes anchored in transactional cooperation, strategic hedging, and infrastructure diplomacy. If the EU remains disengaged – whether in energy, migration, or security – it risks being sidelined from frameworks increasingly shaping its south-eastern neighbourhood.

The EU does not need to endorse Turkey’s vision for Iraq, but it cannot afford to be absent from a process that increasingly affects its core interests, ranging from energy security and migration to regional stability. The EU and its Member States can benefit from leveraging their regulatory influence, financial instruments, and diplomatic coordination where interests overlap, while managing divergence through calibrated engagement.

Nebahat Tanrıverdi Yaşar is a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Applied Turkish Studies (CATS) at SWP. This article is part of a policy series for the “Turkey-Iraq Relations: Opportunities and Tensions in Security and Connectivity” project of the Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) network.

The Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) is funded by Stiftung Mercator and the German Federal Foreign Office.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C43