Colombia’s Path to “Total Peace”

President Gustavo Petro cannot fall back on the FARC blueprint

SWP Comment 2022/C 54, 20.09.2022, 7 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2022C54

Research AreasWith their joint announcement about the desire to resume peace talks, Colombia’s new president and the country’s second-largest guerrilla group, the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional), have sent a clear political signal. The pacification of the ELN is to take place under the aegis of a “leftist” government and be accompanied by a comprehensive and ambitious reform project. This is a renewed attempt to end the civil war following the conclusion of a peace agreement with the FARC rebels in 2016. However, the agreement with the FARC can serve as a blueprint only to a limited extent, not just because of the different historical origins of the two guerrilla groups but also owing to the strongly decentralized internal structure of the ELN. The issues of a ceasefire and the release of prisoners – prerequisites for possible peace talks – remain unresolved. Lengthy negotiations lie ahead, and the involvement of Colombian civil society is essential as central questions about the country’s future must be clarified.

Just four days after taking office, Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, has followed up his announcement about striving for a “total and integral peace” with concrete action. On 20 August 2022, he issued a decree suspending the arrest warrants and extradition requests directed against the ELN peace negotiators currently in Cuba and revalidating the protocols signed back in 2016 so that a “dialogue with the ELN can resume”. In addition, he invited both the so-called neo-paramilitary groups and criminal bands to negotiate with the government and provided an incentive for such a move by ruling out extradition to the United States in the event of serious talks being held. Through this initiative, the president is taking into account the fragmented nature of the conflict in the country, whereby guerrilla groups such as the ELN, rearmed guerrillas of the FARC and paramilitary and criminal violent actors are active on the territory of Colombia and in the border areas with neighbouring states, fighting one another and engaging in clashes with state security forces.

At the same time, Petro has overhauled the top echelon of the security organs, ushering in a new generation of leaders. Following the appointment of new commanders-in-chief, 52 generals in the armed forces and the police force have had to resign, Colombian law stipulates that when a new commander-in-chief of the security forces is appointed, all uniformed officers of his rank or higher have to step down. This decision, together with the transfer of the police from the Ministry of Defence to the new Ministry of Peace, Coexistence and Security, marks the start of what is more than a simply symbolic departure of those leaders in the security apparatus who have been involved in or accused of human rights violations and excessive use of force against the civilian population. The much-criticized ESMAD (Escuadrón Móvil Antidisturbios) special unit, which in the past has been deployed to quell protests and riots and is known for committing abuses, will be affected by this reform process. A new security strategy for Colombia is thereby established – one that is also reflected in a new drug policy (the renunciation of glyphosate use), alternative development concepts and efforts to strengthen the territorial presence of the state.

While these steps taken by the Petro government have created important preconditions that can pave the way for negotiations with the ELN, they are nonetheless insufficient in themselves to guarantee success. Doubts are raised by the large number of failed dialogues, ranging from the peace probes under the government of President Alfonso López Michelsen (1974–78) and the attempts to launch talks in Germany in Mainz and at the Himmelpforten Monastery (1998) to the negotiations under the government of Iván Duque (2018–22). Time and again, the talks were broken off owing to ELN military activities – most recently, the bomb attack on a police academy in Bogotá on 17 January 2019, in which 23 cadets were killed.

The ELN – a difficult negotiating partner

Following the announcement of resumed negotiations with the ELN, parallels have been widely drawn with the peace process involving the FARC rebels in 2016; however, owing to the differences between the two groups, the preconditions for the talks are comparable only to a very limited extent. For example, in contrast with the pronounced vertical and centralized structure of the FARC, the ELN has a very decentralized structure and its individual units are able to act with a significant amount of autonomy. Accordingly, the FARC is described as a “guerrilla that also engaged in politics”, while the ELN has been labelled as an “armed political group” characterized by a quasi-federal structure. Although both groups emerged in 1964 and embraced a Marxism inspired by the Cuban revolution, the ELN is linked to a more urban, student and trade-union milieu, while the FARC is rooted in the rural environment. And although the two groups have sometimes acted together, a great rivalry has developed over time and, on occasion, resulted in fierce battles for the control of certain territories. Beyond Marxism, the revolutionary ideas of the ELN have been spawned by Christian elements of the theology of liberation. An icon of the movement is the priest Camilo Torres, who, together with a group of students, joined the ELN guerrillas in 1965 and was murdered in 1966. It is because of this strong ideological bent of the ELN that the group is much more dogmatic in negotiations than the FARC.

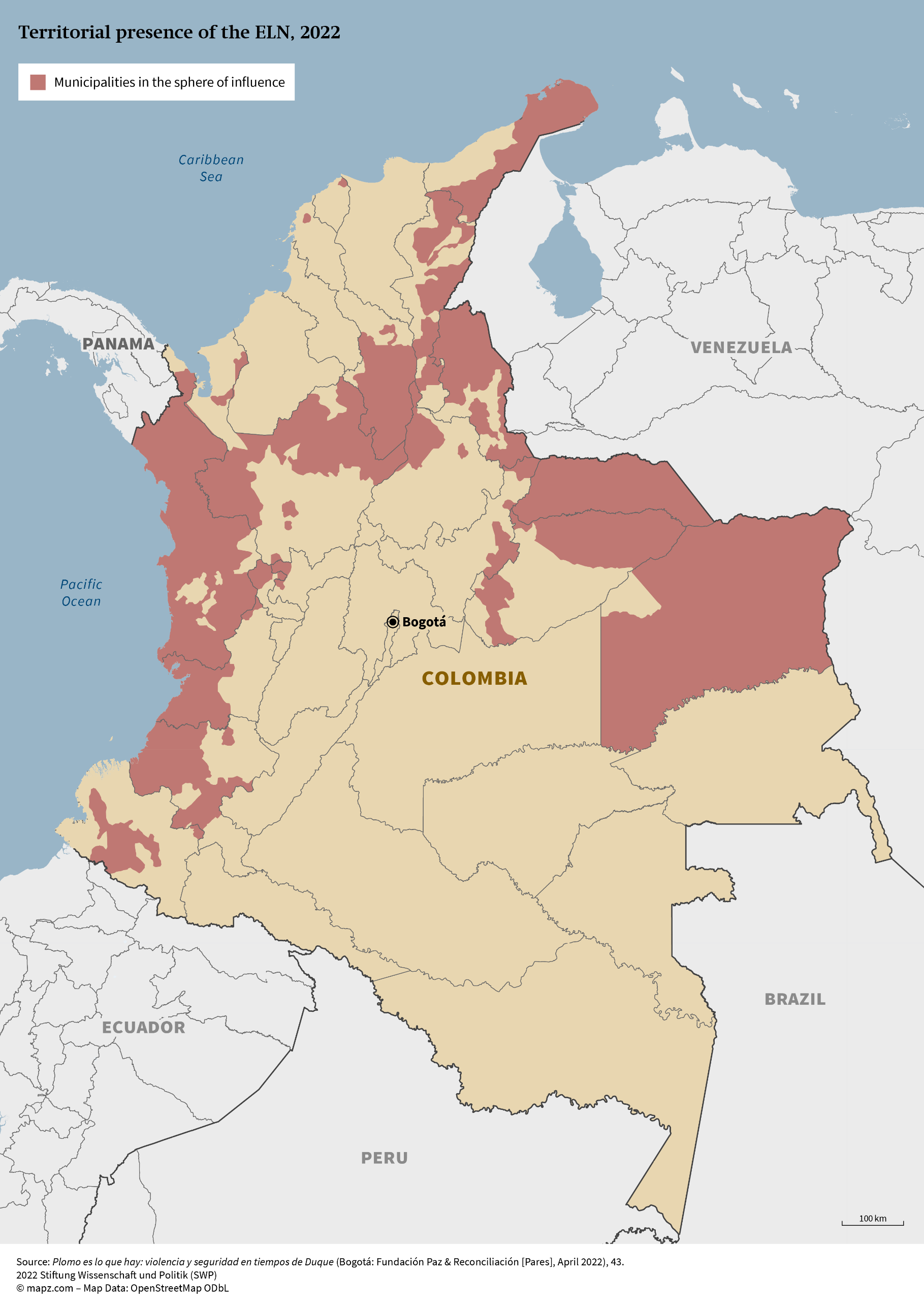

The ELN attacks were directed mainly against the oil industry and mining or the corresponding infrastructure, such as pipelines. They caused significant economic losses and environmental damage. Besides drug trafficking and other illegal economic activities aimed at raising funds, the guerrillas blackmailed transnational companies and kidnapped company representatives and politicians to extract ransom payments. In doing so, the ELN repeatedly sought proximity to social movements and got involved in political work at the local level in order to gain influence on a regional scale. And in order to expand its territorial control, it has killed opposing social leaders and environmental activists. However, the ELN was always much smaller than the FARC – sometimes it had only 1,500 active fighters (compared with the FARC’s 8,000). But after the peace agreement, it was able to take advantage of the power vacuum left by the demobilization of the FARC, expand its territorial presence and increase its ranks to an estimated 2,500 active fighters. At the same time, the guerrillas became more open to the reality of indigenous and Afro-Colombian life and added it to their list of demands. Because of all these diverse interests, many observers call into question the will for peace that the ELN negotiating commission, which is based in Cuba, repeatedly claims to have. Indeed, given its decentralized command structures, it is unclear to what extent the ELN speaks with one voice. In view of the complex internal organization, it is questionable whether the individual military units would, in fact, be bound to possible obligations stemming from a negotiated outcome. The autonomy of the various regional groups (frentes) and their independent military actions have repeatedly brought any peace talks under way to a halt. This must be reckoned with again during the current push for “total peace”. The Central Command (Comando Central) has only limited control over the actions of the approximately seven or eight frentes that are active in 16 of Colombia’s 32 departments and in the country’s major cities (see the map on p. 4). And this does not include the units operating in neighbouring Venezuela. Thus, the lack of a vertical command structure could once again prove to be a serious obstacle in the negotiation process.

That is why this factor must also be taken into account in the talks: the peace agreement of 2016, which offered the FARC the prospect of land distribution and political participation, will not serve as a model for the ELN. For the latter, other issues are paramount: access of the population to the country’s natural resources, the establishment of local means of participation and the concrete form of Colombia’s territorial integration. The ELN is opposed primarily to administrative centralism and transnational enterprises active in the country. It sees itself as a mediator between the state and civil society, giving social organizations a voice vis-à-vis the state and backing their interests. Even in preceding rounds of negotiations under previous governments, the ELN repeatedly ensured that, besides the talks held by the delegations, the dialogue with civil society was promoted at grassroots forums in order to take into account the heterogeneity of regional identities and avoid the impression of negotiations being conducted without the participation of broad social circles. Ever since the ELN was decimated in the 1970s, its military survival strategy has included deep social integration in the areas under its control. This factor, too, will play a role in reaching a peace settlement, since on the one hand the ELN will not want to disappoint the expectations of the neighbourhood committees and protest movements while on the other hand it practises a certain hegemonic paternalism over its social reference groups active in those committees and movements. Operating within this field of tension are the various local groupings, each of which has its own approach to taking action, making it difficult to include them in a joint negotiating mandate.

The role of the international community and national actors

The dialogues between the Colombian government and the ELN that began in neighbouring Ecuador in 2017 and continued in Cuba followed the same pattern as the successful peace negotiations with the FARC guerrillas in 2016: they received international support from countries that were intended to act as “guarantors” of the process (Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Cuba, Norway and Venezuela). But this approach vis-à-vis the ELN failed, not only because of the assassination attempt by the group in Bogotá in January 2019 but also owing to the growing differences between the government of President Iván Duque and the Maduro regime in Venezuela, which eventually led to diplomatic relations being severed.

Thus, the reinstatement of ambassadors to both countries immediately after the inauguration of President Gustavo Petro is an important framework condition for launching the dialogue between his government

and the ELN that was announced in Havana, Cuba, on 12 August 2022. Since the ELN, in particular, operates as a “binational guerrilla” in the Colombian-Venezuelan border area, it is essential to reach an understanding with Venezuela in order to ensure that the organization does not simply relocate its forces to the neighbouring country instead of demobilizing them and facilitating their integration into civilian life. Chile and Cuba have already pledged their support for the renewed peace process, and Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has suggested that the negotiations take place in his country. On 15 September, Colombia and Venezuela agreed to Caracas serving as a guarantor of the peace talks; however, for the ELN, this has implications as Venezuela is also a de facto party to the conflict owing to the presence of the ELN on Venezuelan territory, especially in areas such as the Arco Minero del Orinoco, where many of the country’s natural resources are located and from which ELN itself profits in exchange for safeguarding against illegal mining. Germany (together with the Netherlands, Italy, Sweden and Switzerland) was among those countries that had supported the previous talks and provided useful services for the conduct of the negotiations. It could once again offer such services as advice and technical assistance while playing a role in monitoring an eventual ceasefire as well as transitional security arrangements and implementation mechanisms.

However, international support in itself will not be enough to ensure the negotiations succeed. In contrast with the FARC process, the talks with the ELN will require national actors – such as Churches, social movements and universities – to serve as guarantors that the negotiations directly address the government’s reform plans (such as the reorganization of the internal security architecture, land distribution policy, tax reform, political reform and the redesigning of the development model) as well as the effective implementation of the peace agreement with the FARC and the ongoing political debates in Colombia. To achieve this, it will be important to combine the negotiating skills and extensive experience of Foreign Minister Álvaro Leyva with a broad alliance of national actors who will not only ensure a greater diversity of voices and interests but also boost the much-needed confidence in the negotiations among ELN members and involve the group in a broad social process. At the same time, bearing in mind the experience of other countries, there should be a creative response to the ELN’s demand for a “Convención Nacional” (National Assembly). The regional forums that took place in 2018–19 during the aborted peace process failed to have the necessary widespread impact. Thus, an effort will need to be made at the national level to ensure social actors are involved. Otherwise, the authorities will once again run the risk of the peace process taking place “behind the back” of the country’s population and lacking the necessary legitimacy. Indeed, there have already been many claims that a future peace agreement could have the character of a wholly “elite pact”.

The work of the Asamblea de la Sociedad Civil, which was formed after the coup carried out in 1993 by then President Serrano Elías in Guatemala, and two other bodies that channelled civil protest at that time, the Grupo Multisectorial Social and the Instancia Nacional de Consenso, could serve as a guide for the involvement of civil society. These forums gave a voice to the Churches, business groups and trade unions, indigenous organizations and victims’ associations, with political parties forming a minority among the participants, and came up with joint statements. In this way, a social consensus was achieved. In the Colombian case, in particular, it is essential to involve local actors and the authorities at the local level. Given the special profile of the ENL, conducting negotiations in another country that do not address the processes of national understanding could prove to be a serious stumbling block, since a national legitimacy represented solely by the government is likely to be seen in many quarters as insufficient.

Another important framework condition for the success of the negotiations is the implementation of President Petro’s ambitious reform programme, which corresponds to the ELN’s striving for a transformation of Colombian society that leads to more social justice. This could be the starting point for Germany’s contribution to the peace process. The German government could offer technical and financial support for the implementation of all those new government’s reform projects submitted to the parliament during the peace negotiations and thereby help ensure that results are achieved quickly. In particular, this applies to the establishment of a state presence throughout the national territory so that the size of the area under the control of the guerrillas or other irregular forces can be reduced. Given the decentralized structure of the ELN, it can be assumed that internal disunity and splits within the group will become evident very quickly and that unauthorized violent acts by individual commandos will hinder progress being made in the negotiations. For this reason, the peace agreement with the FARC will be able to serve only to a limited extent as a blueprint for this renewed attempt to broker a similar accord with the ELN. But those elements that featured in the earlier, abandoned talks could provide shortcuts during the negotiations and serve as guardrails.

Nevertheless, in the almost four years that have passed since the dialogue was suspended, there have been important changes. In Colombia, the election of Gustavo Petro provides a new context – one that is both positive, because of the new president’s comprehensive reform programme, and unfavourable, owing to the risks posed by the overload of government activity due to multiple reform efforts being undertaken all at once with limited fiscal resources and precarious parliamentary support. At the same time, the ELN’s presence in neighbouring Venezuela has become much stronger and can be kept under control only to a very limited extent by the Colombian and Venezuelan security forces. The international show of support for the renewed attempt at “total peace” is therefore an important and doubtless helpful initiative. But once again, the key issue will be how and to what degree Colombian society commits to a peace process that is already, and will continue to be, associated with so many uncertainties.

Possible development scenarios: Failure, “sham peace” and breakthrough

The experience of previous attempts to reach a peace agreement with the ELN notwithstanding, the exploratory talks now taking place between the government and the ELN negotiating commission will be decisive in determining whether the two sides can find a propitious starting point for reaching a formal settlement to the conflict. The “federal” structure of the ELN and the decentralized nature of its actions are already being put to the test in terms of whether the group is able to act as one and rein in its own units. How it fares will provide the first insights into the way in which the ELN is dealing with its internal leadership problem, whether the deep-rooted involvement in and economic dependence on legal, semi-legal and illegal territorial economies (gold, coca, timber) can be resolved and to what extent the organization will abandon criminal means of pursuing political goals. If doubts about its intentions prevail, the negotiations could quickly be undermined, despite the good framework condition of a reform-oriented government. A crucial factor here is the role of Venezuela and its government: the ELN has expanded its presence not only into the border areas but also into the interior of the neighbouring country. It has become a factor of social control and territorial domination there and is increasingly coming into conflict with other armed groups and the state security organs. Therefore, it will be decisive whether these binational guerrillas also come under pressure from the Maduro regime to demobilize on Venezuelan territory or whether they are allowed to continue to use that territory as an area to which to withdraw and regroup.

This will also be one of the main points of negotiation for the Colombian government if a “sham peace” is to be avoided. An outcome that does not resolve this issue would not provide for a pacification of the inner-Colombian conflict and would mean society remains polarized. As a result, President Petro’s project of “total peace” would fail, especially since the internal challenges associated with the ambitious reform programme, a difficult security situation and the current precarious fiscal position will entail huge costs to transform society. Given the existing potential for blockades and a political overload, the reform project could quickly run out of steam and thus dampen the inclination to reach a truly comprehensive and far-reaching peace agreement. What is already a heterogeneous base of support for Petro would come under further pressure; centrifugal tendencies and protests would significantly impair its cohesion.

However, despite these difficult framework conditions, a successful peace agreement is conceivable, especially if all parties involved are aware of the unique situation that arises when a reform-oriented government comes together at an auspicious moment with a violent actor expressing their willingness (which, it is to be hoped, is sincere) to make peace. The chance to take advantage of such a historic occasion should encourage national and international actors to ensure this renewed attempt at peace leads to a result that advances the transformation of Colombian society, establishes a peaceful coexistence and helps overcome the existing political polarization. That the ELN leadership has now declared its opposition to the government holding parallel negotiations with other armed groups is not an encouraging sign that the talks will get off to a good start.

At the same time, it is particularly important to do justice to the victims of the protracted conflict and their relatives, as the recently released report by the Truth Commission explains in detail. The requirements for achieving all of the conditions laid out above are stringent, but the opportunity for such a breakthrough should be seized and explored as much as possible so that “total peace” becomes a closer prospect.

Prof. Dr Günther Maihold is Deputy Director of the SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2022

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2022C54

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 55/2022)