The global pandemic crisis has highlighted the inherent weaknesses of governance in countries of the Maghreb. It has underscored Morocco’s lagging human development and infrastructure amid growing authoritarianism. In Algeria, where the government is struggling with an ongoing legitimacy crisis, the pandemic has exposed the state’s weak public services. In Tunisia, the pandemic has emphasised the disarray of the country’s political elites and the effects of the protracted transition on state output. Yet, the pandemic crisis has pushed some of these governments to seize opportunities, including speeding up digitalisation, allowing for citizen engagement, and even seeking some self-sufficiency in terms of medical production. As these countries pursue economic relief and support to overcome the growing economic impacts from the crisis, European partners have the opportunity to use their leverage to promote policies that reduce inequality, prioritise investment in critical infrastructure, and encourage transparent and responsive citizen–government relations.

In the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia fared well by global comparison. Swift and decisive government action in Morocco and Tunisia allowed both countries to limit the initial spread of infections. Even Algeria, which had, by comparison, struggled to put in place and enforce a coherent initial response, did not become a hotspot. However, as the pandemic progresses and as waves of infections continue to hit all three countries, decision-makers are grappling with collapsing health care infrastructure, prolonged economic impacts, and rising popular anger. This confluence of factors presents an unprecedented test of the sustainability of the governance approaches in each country. As public dissatisfaction – driven by long-standing grievances that are now being exacerbated by the pandemic – grows, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia may face greater instability if they do not balance short-term relief efforts with long-term governance reforms.

Initial Response: Decisive Factors

In the first few months, the initial but brief success in Morocco was due to a swift and clear decision-making process, and in Tunisia it was the result of a remarkable – even if ephemeral – elite consensus. The two governments quickly pushed a clear strategy to contain movement, close borders, and limit travel, along with measures to alleviate some of the initial economic impacts of the containment. Both governments incorporated new technology to control population movement and ensure some continuation of daily activities. For example, in a highly publicised effort in Tunisia, robots and drones patrolled the streets. Tunis also sped up previously lengthy and tedious procedures by migrating bureaucratic processes, such as applying for business permits, online. In Morocco, the government’s digital efforts included a health ministry application for sharing up-to-date information with medical personnel.

The two countries also created a range of economic measures to lessen the initial impacts. In Morocco, King Mohammed VI announced the creation of a special emergency fund in March 2020. The fund – which was supported by charitable donations from average to wealthy Moroccans, including the King – was to help vulnerable sectors and be used to upgrade the national health system’s infrastructure. External donors, most notably Germany, the European Union (EU), the United States, Japan, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), also contributed. The government provided stipends (ranging from $80 to $120) to informal-sector workers without social security beginning in April. These payments were made accessible through codes sent to registered mobile phones. In Tunisia, early measures included the establishment of a national solidarity fund, governed by a committee of officials that included union and industry representatives. By October the fund had collected more than $70 million, including from private-sector and external donors. Furthermore, Morocco and Tunisia provided tax breaks and interest rate reductions to support struggling businesses, particularly in the tourism sector. In July 2020, Morocco announced a stimulus package of $12.8 billion, including $8 billion in loans. The government declared a comprehensive recovery roadmap for the private sector – including loans and grants for small and medium-sized enterprises – and reforms in the public sector to lessen its budget burden. Tunisia unveiled a nine-month Rescue and Recovery Plan in collaboration with the IMF in June 2020. The plan included more than $526 million to public projects and allocated $35 million for unemployment payments as well as $245 million to struggling businesses.

In Algeria the state’s initial response was neither as clear nor as effective. The government was slower to implement measures of containment and closures. Still, despite dwindling reserves due to shrinking oil and gas revenues, the government enacted relief measures targeting vulnerable segments of society and for private enterprises. However, the mechanisms of distribution were opaque, and many claimed the funds never reached them. The Algerian government was also relying on civil society networks, including support from Algerians in the diaspora, to provide more relief. In addition to these measures, in July the Algerian government introduced an economic plan to mitigate the impacts of lower revenues from hydrocarbons and encourage economic diversification – including import restrictions – in order to improve liquidity. Many elements of the government’s plan to limit public spending have yet to go into effect, as the government fears a backlash.

Growing Popular Dissatisfaction

According to polls conducted in the spring and early summer, populations in Tunisia and Morocco initially showed satisfaction with and trust in their government’s responses. Algeria, in the aftermath of the Hirak protest movement, which resulted in the removal of former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika and demanded a complete political overhaul, continued to experience a lack of trust and scepticism about official statistics.

As confinements were eased in June and July, cases began to rise shortly thereafter in Morocco and Tunisia. However, as governments failed to maintain the same level of coherence, competence, and control they had exhibited in the initial stages, public opinion quickly changed. Extensive economic ties with and dependence on the outside world, including a need to generate tourism revenue, propelled Tunisia and Morocco to open their airports and ports in the summer. Both countries partly relaxed domestic travel restrictions, which allowed some commercial and social activities to resume by late June. Algeria, where international tourism plays a marginal economic role, remained completely isolated, halting all commercial air and sea traffic. Still, by the fall, infections rose again, even in Algeria, despite strict closures. In all three countries, as the pandemic continued and the economic toll intensified, perceptions of the governments’ responses degenerated across the board.

In Morocco, both private and public health care systems started buckling in the summer and the population struggled. Hospitals were quickly overwhelmed, despite efforts to boost them. Health care workers repeatedly protested poor working conditions. The economic hardships caused by the confinement also worsened the level of public dissatisfaction. By the end of the summer, of the staggering $3.6 billion raised in support funds, $2.6 billion had already been spent. Yet, the government’s tight control of the streets prevented major protests, and most dissatisfaction was voiced online.

In Algeria, Hirak protests – though on a much smaller level – have resumed sporadically, despite official bans on all public gatherings. Furthermore, widespread dissatisfaction with Algeria’s political system manifested in a record low turnout for the underwhelming November 1st referendum on constitutional amendments, indicating the extent to which Algerians reject these changes that the leadership touted as the foundation of a new Algeria.

In Tunisia, by July, the government had collapsed due to corruption allegations involving Prime Minister Elyes Fakhfakh. Ongoing political divisions delayed the formation of a government until September and have impacted the new technocratic government’s ability to manage the continuing health crisis and eroded public trust. The widespread economic and political dissatisfaction with the status quo has driven support for populist political forces – including those associated with the former regime, such as the Free Destourian Party, led by Abir Moussi. Support for these factions has deepened political divisions and worsened the lack of consensus on finding a way out of the pandemic and developing a broader vision for the country’s future.

By the fall, as Tunisia was about to mark the 10-year anniversary of its revolution, protests rose sharply. The widespread economic hardship – compounded by the pandemic –further fuelled the anger of Tunisians. More protests broke out across the country and clashes with security forces increased, resulting in the first casualty in Sbeitla in October 2020. The population’s growing desperation is also seen in the increasing numbers of irregular migrants moving to Spain and Italy from Algeria and Tunisia, despite stronger pushback against illegal crossings.

Across the three countries, in part as a response to growing public dissatisfaction and under the guise of pandemic-related measures, the governments have increased efforts to curb freedom of expression and silence dissent. In Morocco and Algeria, journalists face more intimidation and smear campaigns, and many have been thrown into prison on trumped up charges in recent months. The Algerian government, wary of a wide-scale resumption of the Hirak movement, adopted an amended penal code in April 2020 curbing freedom of expression by allowing the government to punish what it considers to be fake news. Morocco, likewise, attempted to pass a law restricting social media freedoms, but it had to pull back due to the massive backlash online. In Tunisia, bloggers who criticised the government’s pandemic response in spring 2020 faced judicial proceedings. Moreover, with a diminished system of checks and balances, the governments’ efforts towards increasing levels of digitalisation open the door to greater state control and surveillance. For example, in Morocco, mobile applications meant for tracking movements were used to spy on opposition figures. As this environment of authoritarianism and brutal crackdowns continues, it enflames the growing public anger.

All three countries have made significant efforts to procure and build effective vaccination campaigns, with mixed results. Morocco began its campaign first with AstraZeneca and Sinopharm vaccines that have reached a significant number of people. However, there remain challenges of access for many, given the limited availability. Algeria has procured SputnikV doses, while Tunisia is still waiting for its campaign with the BioNTech-Pfizer product to begin. In all three cases, fears related to global disinformation campaigns about the vaccines are present. Whether potentially successful vaccination campaigns in 2021, notably in Morocco, can boost trust in governments once again remains doubtful.

Governance Deficit: Limited Output and Diminishing Legitimacy

By putting long-standing grievances centre stage, the pandemic has exposed the underlying weaknesses of all three governance approaches. Chief among these is the inability of the states to meet their citizens’ needs. Ill-thought-out public policies and lagging and inadequate public services compound issues such as limited economic growth, opaque decision-making processes, and lack of accountability.

These governance deficits present themselves differently in each country. Yet, the outcomes are remarkably similar in all three. In Algeria, a military-led civil leadership has created a rentier system over the years that has distributed the country’s oil and gas revenues to key groups to offset dissatisfaction. In the aftermath of the civil war in the 1990s, the Algerian leadership – claiming legitimacy from their role in the country’s independence struggle and the founding of modern Algeria – used the presence of security threats to justify stark limits on political participation. However, the population grew increasingly disillusioned with the lack of accountability and a closed political system. This became particularly acute in the lead-up to the Hirak protest movement, which began in 2019 and has called for a complete overhaul of the political system. Years of incoherent policies, a lack of economic diversification, and rampant corruption have weakened critical service infrastructure, including health care, and severely diminished the state’s ability to prepare for and manage the viral outbreak. The fact that Algeria’s President Tebboune, who fell ill with Covid-19 in October 2020, was flown to Germany for adequate treatment perfectly exemplifies these failures and follows a long tradition of the country’s elites seeking treatment abroad.

In Morocco, the pandemic is challenging the benevolent authoritarianism narrative and model that the monarchy has sought to emulate. Morocco created a highly centralised system, in which the King holds all political and economic power – a system that is able to deliver some services while also cracking down on dissent. Still, Morocco has failed to manifest efficient public policies and service delivery, and many Moroccans have struggled to access basic needs. Widespread corruption and staggering inequalities throughout the country have highlighted the vulnerabilities of the lower class, and increasingly the middle class. Even prior to the pandemic, Morocco struggled to provide education, health care, and basic infrastructure – including potable water – to many segments of the population. The pandemic’s economic and financial toll further challenges the vision of an efficient, albeit authoritarian, state. The leadership has failed to deliver effective governance that could offset authoritarianism.

Tunisia’s fragile, young democracy faces ideological rifts and a fragmented political landscape that is intensifying the continued economic crisis. The result is deepening social disparities and ensuing contestation, creating a vicious cycle: Demonstrations, strikes, and sit-ins are gaining in force, limiting the government’s room for manoeuvre more broadly, and specifically hampering production in certain sectors. This compounds the downward economic spiral. For instance, Tunisia, a phosphate exporter, experienced a significant drop in production in 2020, forcing it to import the material to cover domestic needs. The pandemic has underlined one of the country’s fundamental challenges: the inability to agree on an economic course that can reduce disparities while taking into account the country’s financial constraints.

Although the weaknesses and failures of each of these governance approaches have been clear for years, the pandemic has put forth a unique test to their sustainability by adding greater urgency and compounding the needs of the population. Without a clear way forward, these political systems risk significant instability.

An Economic Paradox: The Change Needed Is the Change Feared

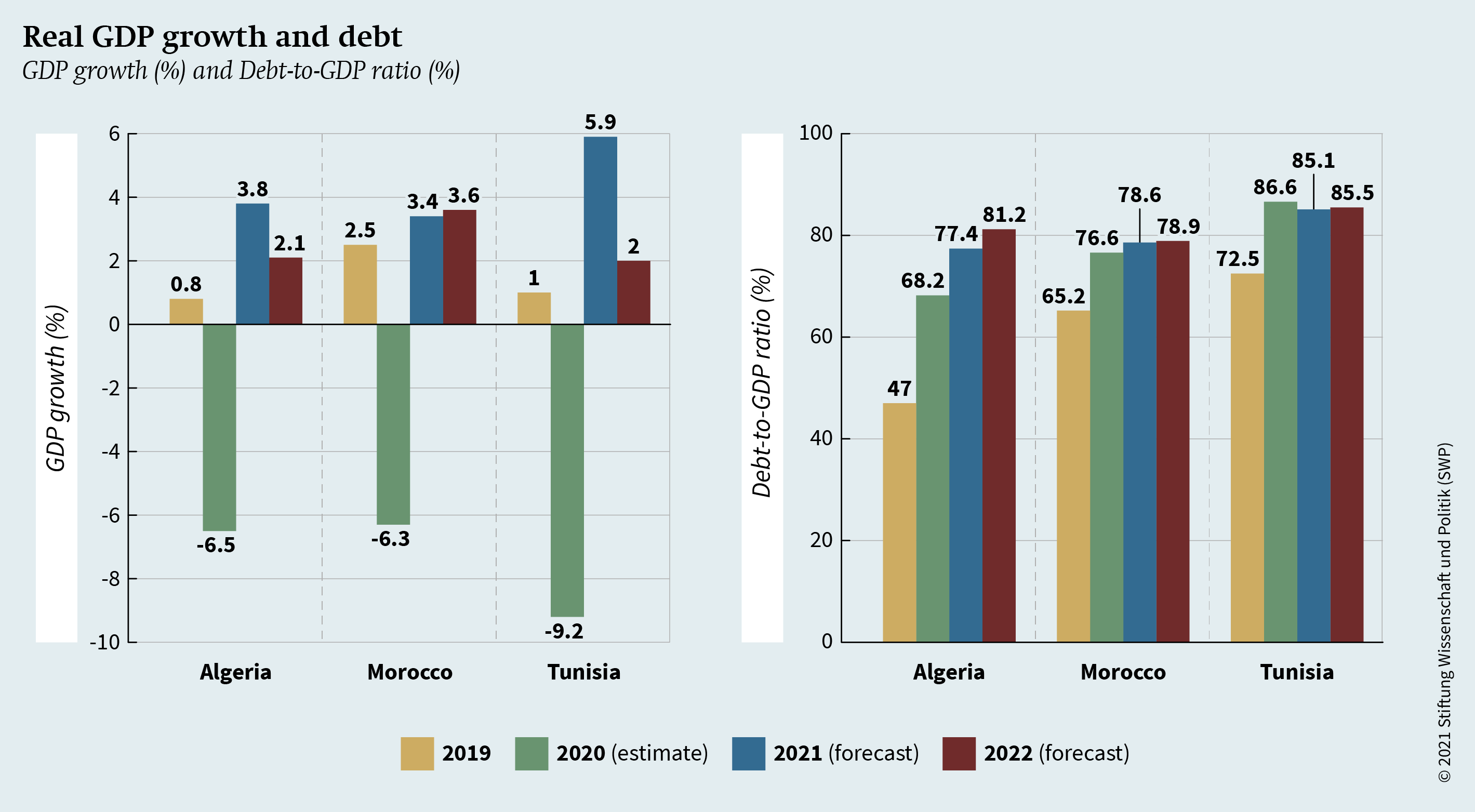

The economies of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia are confronting grim GDP growth and debt predictions (see Figure 1) from domestic and international financial institutions (IFIs). Although specific estimates vary, the significant economic contraction in 2020 will likely yield low-growth rates for 2021. As the pandemic brought social life to a halt, consumption slowed, and in some cases production slowed, dealing a blow to state revenue. In Morocco and Tunisia, losses from diminishing tourism revenue have been notable. Tunisia, where tourism revenue represents 14% of GDP, reported a 77% drop in the number of tourists in 2020 compared to 2019. In Algeria, where energy revenue accounts for 60% of the state budget and 94% of total export revenue – hydrocarbon revenue shrunk by 31% in 2020 compared to 2019. All three countries have also struggled with additional spending to offset some of the initial economic burdens, to support the health care sector, and to acquire vaccines. In the face of rising expenditures and diminishing revenues, Morocco and Tunisia have, in addition to aid from international partners, taken on additional debt, driving up their debt rates as a percentage of GDP (see Figure 1).

One of the inherent challenges facing these governments is that the pandemic’s economic fallout risks slowing or preventing the necessary macro-economic reforms and investments in critical infrastructure. In Morocco, for instance, the government’s recovery plan foresees merging or consolidating state-owned enterprises, yet costlier but crucial sectors – such as education, security, and health care – are excluded from these plans. Thus, critical infrastructure and services for citizens are more likely to deteriorate in the short term.

In Tunisia, the crisis has sharpened disagreements about the country’s economic future. The government needs funding from external actors, including the IFIs, which understand Tunisia’s conundrum and have toned down demands for structural reforms. Yet, even control of wage bills or certain energy subsidies deemed necessary by the IMF appear to be politically highly sensitive, if not unfeasible, with unemployment rates and social unrest soaring. Furthermore, Tunisia’s central bank reported in January 2021 that debt as a percentage of GDP has exceeded 100%, seriously limiting the country’s ability to obtain credit. Rare positive economic news, such as growing liquidity reserves, as in the autumn of 2020, does not signal a general upswing but is merely related to decreased consumption due to Covid-19.

In Algeria, the pandemic’s economic fallout is speeding up the looming liquidity crisis, which will not only prevent the government from buying social peace, as it had in the past, but will also halt efforts to diversify the hydrocarbon-reliant economy. So far, President Tebboune’s government has repeatedly ruled out borrowing from the IMF or the World Bank.

The measures that the governments of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia have undertaken so far do not represent effective long-term solutions, which limits their chances of overcoming a profound economic crisis. The situation thus promises to be tenuous at best, and it is likely to increase inequality and drive popular anger and protest movements.

Capacity for Adaptation?

As the three countries deal with the pandemic’s pressures and their impacts on long-standing issues, the governments must find the right path forward. Whether this global pandemic can provide the needed impetus for change remains an open question.

Algerian decision-makers face a particularly urgent question: Should they abandon the heavily centralised economic approach in favour of a more liberal and open economic policy? So far, the elites have vacillated between the two. In 2019 a new, more liberal hydrocarbon law was passed that is aimed at stimulating foreign investment, while at the same time protectionist measures, such as import restrictions, are applied haphazardly for short-term relief; meanwhile tax and fiscal policies are overdue for reform. The lack of trust and the absence of transparency and accountability remain key challenges. Even if current power brokers – business interests and the military – with competing clientelist agendas were to agree on profound reforms in the interest of their own survival, it is unclear whether the population would give them the benefit of the doubt. Yet, in many ways, the authoritarian model remains resistant and is still managing to co-opt, divide, and buy off dissenters, even if with less success than in the past. A profound and decisive reform plan is necessary for Algeria to move forward, as piecemeal reforms are unlikely to address the current challenges and ensure stability.

Morocco and Tunisia, likewise, will also have to push forth comprehensive reforms to rise to the challenge, even if Morocco in the past has proven to weather shocks quite well. Here the most significant challenge to passing sweeping economic and political reform is entrenched interests, particularly that of the monarchy. Although Morocco has favoured an open economic approach – generating significant foreign investment over the years and diversifying away from agriculture to build manufacturing and production infrastructure – the progress has ultimately been successful mainly to the extent that it has not threatened the monarchy’s own business interests and the interests of those closest to it. For example, the monarchy remains in control of key sectors, thereby keeping foreign and even domestic investors out. In Tunisia, the lack of consensus on a path forward for economic development and the failure to develop a robust governance approach have enflamed popular anger. Exactly 10 years after the revolution, Tunisians’ hopes for economic prosperity are dwindling, social peace is elusive, and public trust in democracy is low.

Yet, the pandemic crisis has created some opportunities for innovation and social entrepreneurship, and even a degree of self-reliance. The three governments encouraged private-sector actors to produce ventilators domestically for their respective health sectors. Moroccans even produced a locally made diagnostic kit for SARS-CoV-2. The increased citizen engagement has also been a ray of hope. Civil society groups in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia have played an important role in raising community awareness, distributing masks, and delivering aid to the most vulnerable. Due to their own limited capacities, governments at times have had no choice but to rely on such citizen engagement. In Algeria, officials prided themselves in licensing 4,000 civil society organisations within a month and half. Certainly, this bears the risk of an inflation of GoNGOs (government-supported non-governmental organisations), thereby shielding the government from criticism or competition. Yet, a number of local initiatives are building on previous efforts to reform the system, not through contestation but through citizen engagement, including private-sector actors. Hence, these pandemic-related openings may present an opportunity to rebuild citizen engagement, strengthen the role of the private sector, and foster strong, decisive, and innovative governance approaches.

However, greater and more systemic changes are necessary. Without those, the pandemic may prove to be a catalyst for instability and social unrest as the gulf widens between the few prosperous segments of society and the greater number of vulnerable communities. Although the leaders of these countries understand the gravity of the situation, they have yet to undertake promising reforms. Whether these governments are able to adapt will depend on a few key determinants. For one, the extent to which these countries are able to restore some degree of trust in their institutions will require crafting longer-term recovery measures that produce more tangible outputs for the citizens. A further indicator of the capacity to adapt is the degree to which these countries – particularly Morocco and Algeria – ease the crackdown on freedom of expression. Finally, more thoughtfulness and consensus around a realistic economic and social vision for all three countries requires compromise – and even personal sacrifice by the governing elites. Whether they are prepared to do this is unclear.

Maghreb-EU Cooperation: A Chance to Rethink Old Practices

The EU and its members states – the Maghreb region’s most important partners – can play a crucial role in supporting governance reform in the Maghreb, even during this difficult period. European policy-makers have an opportunity in this moment of change to rethink their own practices and perceptions. The political elites in countries of the Maghreb have managed to muddle through, in part because of international support. This support has at times been unconditional – with significant financial, political, and diplomatic backing – to maintain regional stability. The pandemic’s impacts may provide a greater impetus to support these governments unconditionally – especially in terms of emergency funding and relief, and to address shorter-term threats of insecurity and instability. However, this has to be done without overshadowing the long-term challenges of building sustainable economies and equitable societies.

Economic and fiscal challenges in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia will increase their reliance on the EU for economic and financial support. This presents an opportunity to encourage better governance practices. In this situation, European partners may be tempted to direct aid primarily through governments. This should not come at the expense of support to elected institutions and civil society. In short, the broader the ownership and buy-in, the more chances for success. A key effort in supporting these countries is to ensure that funding, international messaging, and conditions accompanying cooperation reflect citizens’ priorities. A systematic and rigorous focus on governance and service delivery in Euro-Maghrebi cooperation will lay the foundation for relations and credibility with those that matter most: the populations in the Maghreb.

In doing so, it is worthwhile to acknowledge the differences between the countries and to adjust measures to the specific contexts accordingly. This implies rewarding each country’s progress in key areas: economic and human development, civil and political liberties, and security. In terms of the increase in crackdowns on freedom of expression in Morocco and Algeria, European partners should remember that the countries’ chances of overcoming the enormous social inequalities are stronger with more freedom of speech and expression, not with less. In Morocco, the taboo of discussing the monarchy’s involvement in the economy prevents discussions on an equitable and effective governance approach. In Algeria, more outspokenness regarding the intensifying crackdown is necessary.

Tunisia needs ongoing funding and benefits to support reforms towards more effective governance, and to protect the democratic progress. This will signal that democratisation, even in trying times, still matters to European policy-makers. In doing so, European partners are well advised to systematically incentivise domestic cooperation and consensus-building in Tunisia. This can be achieved by rewarding cooperation across party and institutional boundaries. Germany’s reform partnerships, which allocate funds once common benchmarks are met and require coordination across several ministries, are a step in this direction.

Algeria is in need of profound governance reform, as the very foundation of its rentier economy is eroding. At the same time, Algeria is the partner with the most strained European relations – due to France’s bloody colonial past and Algeria’s sovereign pride. Given these sensitivities, the country has signaled that it would benefit from technical cooperation to lay the foundation for a new economic policy. European actors should encourage such cooperation to be inclusive and support engagement by civil society actors such as economic think tanks and independent private businesses.

Finally, international debt relief discussions for Africa have so far not included the (lower-) middle-income countries of the Maghreb. An option here is to focus on grants rather than credits or loans in the case of Morocco, and even more so Tunisia. This is how European partners can generate goodwill with the governments and the populations while encouraging governance approaches in a sounder and more sustainable direction.

Intissar Fakir is a fellow and Editor in Chief of Sada in Carnegie’s Middle East Program. Dr Isabelle Werenfels is Senior Fellow in the Middle East and Africa Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2021

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

doi: 10.18449/2021C15